Six Kings' Daughters- Cunningham (WV) c1867 Cox B

[From Folk-Songs of the South; Cox, 1925; There's an excellent report on the informant in the Introduction, including an autobiography. Cox's notes follow.

R. Matteson 2014]

Introduction with autobiography of G.W. Cunningham:

The first genuine ballad-singer discovered was Mr. George W. Cunningham, Elkins, Randolph County. He was attending the Summer School in the session of 1915 when the Society was organized. He not only knew some of the traditional ballads but he sang them to Professor Barnes, who communicated both words and music. These songs were, "The House Carpenter" (Child, 243), "The Greenwood Siding" (Child, 20), "Six Kings' Daughters" (Child, 4), and "Barbara Allen" (Child, 84). Five other songs were reported by Professor Barnes as having come from him. His interest in the movement prompted his appointment as an Official Correspondent. Eight songs secured from other persons were communicated by him, making a total of seventeen contributions. I heard him sing some of the old songs on one occasion only. He sang in a loud, strong voice that had good carrying qualities. His personality and character can best be gathered from his photograph and his autobiography, which is as follows:

[Dated at Elkins, Randolph County, January 8, 1922.] I was born February 8, 1858, close to the Upper Fork of Cheat River, in Randolph County, West Virginia, then Virginia. My father was Jackson Cunningham, a poor man of unsettled, roving disposition. He removed eight or ten times during the nineteen years of his married life, my mother dying when I was sixteen years of age.

I was about ten years old when I started to school, but I had learned at home so that I could go with about the most advanced classes, and when school closed in about seven weeks, I "stood head" in an advanced spelling class many of whom were nearly twice as tall as I. I soon knew the multiplication table on "Hagerstown Almanac" to 25 times 25, and could do any common problem in fundamental rules or fractions, much more quickly mentally than I can now by figures. The morning I was eight years old I tried to calculate how many seconds old I was, but could not well remember the result.

During my narrow life between ten and twenty years, I managed to attend the crude country schools for about fifteen months, mostly under poorly prepared teachers; but I attended county Normals in Barbour County for four months in 1878, making a first grade certificate that fall in a text book test fully as exacting as I've ever seen under the uniform system.

This is my fortieth year as teacher and grade school principal, and my sixty-fifth term of school, three of which were subscription terms; my first three terms were taught in Barbour County, all the rest in Randolph County.

I have lived in Randolph County all my life, practically, except four years I lived in Barbour County. Living upon small farms owned by me in Dry Fork and Leadville districts successively, I made an honest though frugal and restricted living by teaching and farming in combination, as circumstances allowed.

When nearly twenty-six years old, I married Miss Mollie Hamrick of Barbour County, whose father, Graham Hamrick, emigrated in the late fifties from Rockingham County, Virginia, to Barbour County, rearing there a family of eight children by teaching singing schools, and by other strenuous employments. In his old age he discovered a wonderful process of embalming, but was too handicapped and feeble to handle it successfully.

My wife and I reared eight children, five girls and three boys, to mature age, the girls all being successful and popular teachers for some years. The mother passed to her reward on October 4, 1921.

My grandfather, Stephen Cunningham, was a native of Highland County, Virginia, and was of Irish descent. His father, William Cunningham, came across from either Ireland or Scotland, and had many awful adventures with the Indians. My mother was Eleanor Wimer, a native of Pendleton County, West Virginia. Her father and mother were of Dutch or German descent. Her father, George Wimer, reared a steady, industrious family of twelve children, and her grandfather, Henry Wimer, was one of four brothers who came to Virginia from either Holland or Germany.

I am near sixty-four years old, five feet ten inches tall, weigh now one hundred eighty-five pounds; complexion dark, blue eyes, fair skin, hair fast turning gray. I was really never under the care of a physician, never had a fever, never had a dentist in my mouth except to extract a few teeth, never danced, never drank spiritous liquors of consequence. I pay my debts, try to attend to my own business, and am vitally concerned in the welfare of my posterity and of our country.

My father was a charming singer, though he knew nothing of the science of music. He sang many thrilling folk-songs and ballads. My mother could carry but few tunes. I was deeply interested in music from early childhood, learning all the songs and hymns that I could find. My people and acquaintances were mostly singers of songs. One of father's sisters, who never married, lived with us and taught me sketches of several rich old English ballads. Laban White, of Dry Fork District, taught me a few, but Ellen Howell, a noted woman who lt worked round " and mingled freely in social pastimes, often lived with us, and freely taught me many folk-songs, ballads, and ghost stories. She, late in life, married an old widower named John Eye.

The social gatherings and entertainments of my early days were rather restricted and crude, and rough, yet they were generally real and impressive, and though my chance of mingling in them was narrow until I was about seventeen, yet I got a peep sometimes as most people do, ofttimes to their regret. House-raisings, log-rollings, corn-huskings, apple and pumpkin-cuttings, bean-stringings, kissing-plays, and last, but not least, drunken frolics were the order of the times among most of the people. Very generally the gatherings ended with a dance or play-party. Of course there was often some rough and lewd conduct, though I doubt whether there was really as much vicious conduct then as now, except in the line of drinking, which was almost universal then.

LADY ISABEL AND THE ELF KNIGHT (Child, No. 4) Notes by Cox

This ballad is known in West Virginia as "Pretty Polly," "Six Kings' Daughters," "The King's Daughter," "The False Lover," and "The Salt-Water Sea." Nine variants have been recovered.

For American variants see Child, M, 496 (Virginia; from Babcock, Folk-Lore Journal, VIII, 28) ; Journal, XVIII, 132 (Barry; Massachusetts) ; XIX, 232 (Belden; Missouri); XXII, 65 (Beatty; Wisconsin), 76 (Barry; New Jersey, tune only),

374 (Barry; Massachusetts; from Ireland; also readings from other texts); XXVI, 374 (Mackenzie; Nova Scotia; cf. Quest of the Ballad, pp. 93, 174, 183); xxiv, 2)33, 344 (Barry; Massachusetts and Illinois; from Irish sources); XXXVII, 90 (Gardner; Michigan); xxviii, 148 (Perrow; North Carolina); xxxv, (Tolman and Eddy; Ohio); Wyman and Brockway, p. 82 (Kentucky); Campbell and Sharp, No. 2 (Massachusetts, North Carolina, Kentucky, Georgia); Focus, IV, 161, 212 (Virginia); Child MSS., xxi, 4 (4, 6); Minish MS. (North Carolina). In Charley Fox's Minstrel's Companion (Philadelphia, Turner & Fisher), p. 52, may be found "Tell-Tale Polly. Comic Ballad. (As sung by Charley Fox.) "

For references to American versions, see Journal, xxix, 156, note, 157; xxx, 286. Add Shearin and Combs, p. 7; Bulletin, Nos. 6-10. For recent British references see Journal, xxxv, 338; Campbell and Sharp, p. 323.

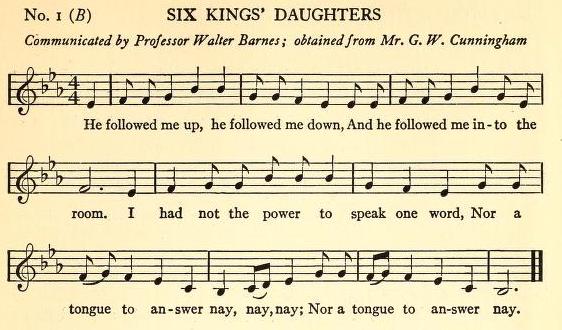

B. "Six Kings' Daughters." Communicated by Professor Walter Barnes, Fairmont, Marion County, July, 1915; obtained from Mr. G. W. Cunningham, Elkins, Randolph County, who learned it shortly after the Civil War from Laban White, Dry Fork. Printed by Cox, xliv, 269.

1 He followed me up, he followed me down,

And he followed me into the room;

I had not the power to speak one word,

Nor a tongue to answer nay.

2 "Go bring me some of your father's gold

And some of your mother's fee,

And I will take you to Scotland,

And there I'll marry thee."

3 She brought him some of her father's gold

And some of her mother's fee;

She took him to her father's barnyard,

Where the horses stood thirty and three.

4 "Mount on, mount on that pretty, pretty brown,

And I on the dapple gray;

And we will ride through some long, lonesome woods,

Three long hours before it is day."

5 She mounted on the pretty, pretty brown,

And he on the dapple gray;

They rode on through some long, lonesome woods,

Till they came to the salt-water sea.

6 "Mount off, mount off your pretty, pretty brown,

And I off the dapple gray;

For six kings' daughters have I drowned here,

And you the seventh shall be."

7 "O hush your tongue, you rag- villain!

hush your tongue!" said she;

"You promised to take me to Scotland

And there to marry me."

8 "Haul off, haul those fine clothing,

Haul off, haul off," said he;

"For they are too costly and too fine,

To be rotted all in the sea."

9 "Well, turn your face toward the sea,

Your back likewise to me,

For it does not become a rag- villain

A naked woman for to see."

10 He turned his face toward the sea,

His back likewise to me;

I picked him up all in my arms

And plunged him into the sea.

11 "O help, come help, my little Aggie!

Come help, I crave of thee,

And all the vows I've made unto you,

I will double them twice and three."

12 "Lie there, lie there, thou rag-villain,

Lie there instead of me;

For six kings' daughters have you drowned here,

And yourself the seventh shall be."

13 I mounted on the pretty brown

And led the dapple gray;

I rode home to my own father's barn,

Two long hours before it was day.

14 "O what is the matter, my little Aggie,

That you call so long before day?"

"I've been to drown the false-hearted man

That strove to drown poor me."

15 "O hold your tongue, my little parrot,

And tell no tales on me,

And your cage shall be made of the brightest bit of gold,

And your wings of pure ivory."

16 "O what is the matter, my little parrot,

That you call so long before day?"

"A cat came to my cage door,

And strove to weary off [1] me,

And I called upon my little Aggie

To come and drive it away."

1. For worry of: cf. Child, C, 17.