No. 75: Lord Lovel

[Lord Lovel, which Bronson called "too too insipid," became, like Lord Bateman (Young Beichan), popular in the 1800s through various print versions and parodies; eventually becoming a parody of itself. By the 1830s versions were printed in the "comic" 5-stanza form in the United States and in England a broadside (Child Ha) was published in 1846 by James Dixon. In 1847 (and again in 1853) a comic version was published in Davidson's Universal Melodist, I, 148 (Child Hb). As an attempt to burlesque the ballad it included an "original stanza" as well as spelling "buzzum" for bosom and "lovier" for lover. Popular English Music Hall performer Sam Cowell (1820-1864) sang this comic arrangement of "Lord Lovel" in his Music Hall performances. Cowell came to the US when he was two and was child actor, comic and singer. He possibly learned the comic version in the States from his father, the noted English actor, Joseph ("Joel") Cowell or from popular comedian singers like James Howard, whose version (1836- BBM) was published in Hadaway's Select Songster (1840). Sam Cowell returned to England in 1840 and he helped popularize "Lord Lovel" as a comic song, publishing it by 1850. [Howard of Brighton Theater, was born in London in 1798 and made his first bow in America playing the character of Henry Bertram in 1818. He sang at Niblo's Garden with great success in 1835 and it was there he performed lord Lovel- Records of the New York stage: from 1750 to 1860, Volume 1 by Joseph Norton Ireland.]

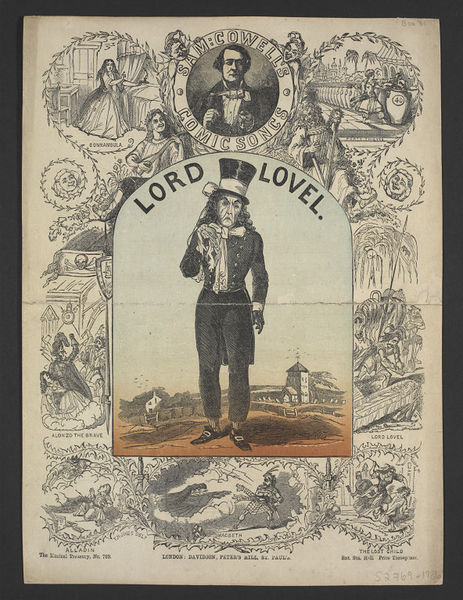

From Sam Cowell's Comic Songs; 1850

The simple story line (where both lovers die) was not originally comic in nature and according to James Dixon, Lord Lovel is "a very old Northumbrian ballad." The first extant version dated February 1765 entitled, The Ballad of Lady Hounsibelle and Lord Lovel (Percy's title), was enclosed with a letter from Horace Walpole to Thomas Percy. After Percy's papers were acquired at an auction by the British Museum this ballad was discovered in a volume of Walpole's letters and was first published in 1904 in "The Letters of Horace Walpole: Fourth Earl of Oxford" edited by Helen Wrigley Toynbee & Paget Jackson Toynbee, published 1904, Clarendon Press, pp.180-184. Since this was published several years after Child's death it was not included in ESPB.

It's important to note that Walpole learned this ballad 25 years before he wrote this letter to Percy with the enclosed ballad. Therefore the date would be 1740.

The letter and ballad text are found in my collection in English and Other Versions and also attached to the Recordings & Info page. They are taken from The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole's Correspondence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937-1983) which provides free online access to all 48 volumes of W.S. Lewis’s scholarly edition of the correspondence of Horace Walpole (1717-1797), youngest son of Sir Robert Walpole, England's first Prime Minister.

Because of the close similarity of Walpole's version and Percy's (two versions supplied by Rev. P. Parsons of Wye), it reinforces the Percy text (Child A, see below) which Child says the Rev. Parsons of Wye sent an edited version in 1770 and again after that in 1775 sent the original. Percy does not mention or acknowledge Walpole's text, which he knew about (assuming he read the letter), and Walpole's version remained in his papers undiscovered until the early 1900s.

Child A is another story. The first Child text, Lady Owncibell, was supplied by Rev. P. Parsons of Wye in a letter sent to Percy and dated May 22, 1770. This version is in Parsons' hand and is authentic. A second similar version, in an unknown hand, was among the papers. Someone has written "Parsons 1775" in the left hand corner. This second version is difficult to authenticate, the source of the hand and date are not certain and the date was added by another hand. The second version, Lady Ouncebell, is Child A. It is similar to the first with minor changes, the most important being a different spelling of the title. Clearly the two are from the same source. Perhaps Parsons had someone redo the ballad in a neat hand but why didn't he mention sending Percy a second version in his letter of 1775. Child, for his part, said the second version was the original without offering any proof. Parsons never mentioned the second version in any of his three letters.

Parsons wrote, "I suspect it should be Dowsabell" on the MS (Dowsabell, meaning sweetheart). This is important because it may supply the "original" name of the ur-ballad which has naturally progressed to "Nancy Bell" in the comic one. Ballads using the "downsabell" name or derivative would likely be older and closer to the older, original ballad. Similarly ballad versions using the quatrain form (or the quatrain with an exact repetition of the last line) would likely be older and closer to the ur-ballad.

Thus we see that Lord Lovel is really two similar ballads; the "old Northumbrian ballad" and the newer, popular "comic" version which has the 5-line form. The ur-ballad, of course, is the older form, dated back at least to 1740 (Walpole). This older form is represented by Child A, B, C, D, E, G, while the newer 'comic' form is found in H with F, a variant of the H tradition. Child I is misplaced and should not be considered a version of Lord Lovel.

* * * *

The versions from North America pre-date and are similar to Child H which is a broadside first published in Ancient Poems, Ballads and Songs of the Peasantry of England, p. 78; Volume 17 edited by Dixon in 1846. Dixon says, "THE ballad of Lord Lovel is from a broadside printed in the metropolis during the present year. A version may be seen in Kinloch's Ancient Scottish Ballads, where it is given as taken down from the recitation of a lady in Roxburghshire. Mr. M. A. Richardson, the editor of the Local Historians Table Book, says that the ballad is ancient, and the hero is traditionally believed to have been one of the family of Lovele, or Delavalle, of Northumberland: the London printers say that their copy is very old. The two last verses are common to many ballads. From the tune being that to which the old ditty of Johnnie o’ Cockelsmuir is sung, it is not improbable that the story is of Northumbrian or Border origin.

In a response to an inquiry about the origin of Lord Lovel (Notes and queries - Page 449; Oxford Journals, 1870) Chappell wrote: "Lord Lovel" is a modern burlesque ballad in imitation of an ancient one, entitled "Fair Margaret and Sweet William," printed in Percy's Reliques of Ancient Poetry. "Lord Lovel" will be found in The Casket of Comic Songs, etc., p. 9, as well as in Davidson's Universal Melodist, edit. 1847, i. 148, with the music. The authorship is unknown. It first became known in the metropolis by a comic singer of the name of Graham; but it was not received with eclat until poor Sam Cowell brought a copy of it in his pocket from Aberdeen about the year 1846, when it became a favourite song at Evans's and other Music Halls of the metropolis.

To this Dixon replied: "Lord Lovel" (41* S. v. 449.)--The reply to the query of Edgar (ut supra) is altogether wrong, "Lord Lovel" is not a "modern burlesque," but a very old Northumbrian ballad, which has been familiar to me from my childhood and long before Sam Cowell's popularity. I inserted the ballad in the Percy Society's edition of Ancient Poems, c/c, of the Peasantry (1846). I had then several old broadsides before me, printed by Brockett of Durham, Angus of Newcastle, Pitts of Seven Dials, &c. &c. I made use of these various copies. The ballad is also in different collections which I possess, but to which I cannot have access while travelling on the Continent. There is nothing particularly "comic" about "Lord Lovele"—for that is the proper title. In Kinloch's Ancient Scottish Ballads is a traditional version, printed long before Sam Cowell was the idol, or rather the buffoon, of the cafe chantant. As to "Lord Lovell" being taken from "Fair Margaret and Sweet William," I think it much more likely that the reverse is the case. A ballad that introduces a "parish clerk" can have no especial claim to antiquity. The music is the old Border tune of the "Reach i' the creel": it was probably obtained from Graham, who, judging by his name, was probably a Borderer or a North Briton. There are several songs to the same air.

My friend Mr. Chappell, I am aware, considered "Lord Lovel" as modern. There are few men whose statements and assertions are more accurate; but in the above instance he "nodded," as Homer is said to do sometimes, and made an evident mistake. James Henry Dixon."

* * * *

In 1929 Barry (BBM) wrote about Sam Cowell and provided a better overview: "The history of the tradition of "Lord Lovel" may thus be tentatively made out. A version of the ballad, textually akin to Child H, and sung to a relatively modern, commonplace melody, had the misfortune to be taken up by the comic stage, probably about the second decade of the last century. It won popularity, was printed in America in the 1830's, and continued to be a favorite for a number of years on both sides of the water. Sam Cowell's singing of the ballad, and the Ditson print gave it such a lease of life that it became one of the best known of traditional songs, yet, as recorded many times from singing, showing but little tendency to verbal change (such as the metamorphosis of the unfamiliar St. Pancras into Pancry, Pancridge, Patrick, and Peter), with even less melodic variation. It has never quite freed itself from the effects of its early evil associations."

The ballad text itself is not comic in nature but the form, which features a repeated word (or syllable) at the end of the 4th line. The 4th line is then repeated as the 5th line which extends the last line into two lines. This form, usually sung in a major key, makes the text comic. When this form became attached to lord Lovel is unknown. The "comic" 5-line form was found in the US in 1812 and surely dates back to the late 1700s.

I assume, and we can judge by some of the early versions, that the original ballad did not have this form and was in a standard quatrain. According to Dixon, and I concur, the older ballad dates back to the early 1700s at least. "The Ballad of Lady Hounsibelle and Lord Lovel" Percy's title for Horace Walpole's ballad is dated 1740. The older forms are represented by the names Hounsibelle (Walpole 1740) and Owncibell (Parsons 1770) rather than Nancy Bell which is a logical derivative. Parsons wrote, "I suspect it should be Dowsabell" on his letter (Dowsabell, meaning sweetheart) which I believe may be the ur-ballad woman's name.

* * * *

Many collectors have attributed the versions from North America to Child H, the English broadside of 1846 which has the "comic" 5-line stanzas. To attribute the following (first stanza only, from James Ashby's MS ballad-book, where it is dated January 26, 1812) version found in Missouri to the broadside is absurd:

Lord Lovel he stood at his castle gate

A-combing his milk-white steed,

When up came Lady Nancy Bell

To wish her lover good speed, speed, speed,

To wish her lover good speed.

This predates the broadside by 34 years and since it was found in Missouri it surely dates back to the 1700s. The ballad, in the 'comic" form, clearly predates the broadside and ballads from tradition were not based on it but were based on an earlier ur-ballad from which the broadside was "composed" (written down).

Now consider this version from around the same date contributed by Dr. John W. Wayland. It was written down from memory in 1849 by his mother (nee Anna M. Kagey) of Mt. Jackson, Va. Shenandoah County.

1. Lord Lovel stood at his castle gate,

Combing his milk-white hair [steed],

Up came Lady Nancy Belle,

To wish her lover good speed.

It's simply the same ballad without the extended 4th line which makes the ballad seem like a parody. This form, found in many old ballads, became attached to the ballad, and the ballad in this form became a parody of itself.

Barry adds, "Our D-text, together with a longer County Sligo version, sung in Vineland, N.J., belongs to the earlier, better tradition of the ballad. This old tradition is represented by Child A, C, E, G, J, of which G calls the lady Isabell, and the others have retained some corruption of "Ann Isabel," To the same group belong Cox C, and one of the five texts in the Child MSS referred to by Professor Kittredge (JAFL, XXIX, 160), a text of Irish origin, which calls the heroine "Lady Ann, sweet bell(e)." The mood of this group of texts is serious, as is that of Child B, D, in which the lady is Nancybell, Nanciebel. Child F has a touch of sentimentality, which, in H, easily degenerates into comedy."

Barry apparently did not know Parsons wrote, "I suspect it should be Dowsabell" on his letter. Dowsabell, meaning sweetheart, is perhaps the source of the name "Ann Isabel."

The ballad is similar To Lord Bateman (Young Beichan) in that the hero needs to leave to visit far away lands "some strange countries for to see." He has a premonition that he must return to his Lady Dowsabell (Nancy Bell) and she dies before he can return. The ending is similar to "Fair Margaret and Sweet William" as Lovel orders the casket be open and he kisses her lips and dies shortly thereafter (in Child E he stabs himself) of sorrow. The "rose and briar" ending found in "Fair Margaret" and "Barbara Allen" usually concludes the ballad. Again, as in Child 74 (Fair Margaret), his death may be attributed to kissing a corpse, although this is not stated (as in Child 49). In most cases, we must presume he died of sorrow, a common malady in ballads. Consider this, from a native of County Sligo- taken down in NJ in 1906:

It's often and often I've kissed your luby lips,

But we never shall kiss after dyin'!" [Lord Lavell, Rasvior, 1906- Barry BFSSNE]

* * * *

The name of the church in the 1846 English broadside and copied by various print versions is usually St. Pancras for St. Pancras Old Church, which is in the southern half of the London Borough of Camden parish, and is believed be one of the oldest sites of worship in Great Britain. It appears in US print versions as St. Pancry in 1839 and as St, Pancras in 1840. The 1846 English broadside may be taken from the 1840 Hadaway's Songster (or early print version).

* * * *

In the US there are a handful of versions that are from the older tradition of the ballad as established by Child A-E, G. They may easily be determined by the "How long" stanza. Versions from the US are:

1) Cox B; "Lord Leven" date Communicated by Mrs. Hilary G. Richardson, Clarksburg, Harrison County, who obtained it from Mrs. Nancy McDonald McAtee.

2) Brown A. "Lord Lovinder.' Circa 1900 from the John Bell Henneman collection, from North Carolina.

3) Barry; "Lord Lavel" date 1906, from Bulletin of the Folksong Society of the Northeast; Vol. 1, 1930.

4) Barry D; 3 stanza fragment from BBM, 1929.

5) Brown D; fragment from "Aunt Nancy Coffey, who lived in the Grandfather section of Caldwell" which has the "how long" stanza.

R. Matteson 2013, 2015]

CONTENTS:

1. Child's Narrative

2. Footnotes (Found at the end of the Narrative)

3. Brief (Kittredge)

4. Child's Ballad Texts A-I [One additional version J is given in the Additions and Corrections]

5. Endnotes

6. Additions and Corrections

ATTACHED PAGES (see left hand column):

1. Recordings & Info: Lord Lovel

A. Roud Number 48: Lord Lovel (350 Listings)

2. Sheet Music: Lord Lovel (Bronson's music examples and texts)

3. US & Canadian Versions

4. English and Other Versions (Including Child versions A-J with additional notes)]

Child's Narrative

A. 'Lady Ouncebell,' communicated to Bishop Percy by the Rev. P. Parsons, of Wye, 1770 and 1775.

B. 'Lord Lavel,' Kinloch Manuscripts, I, 45.

C. 'Lord Travell,' communicated by Mr. Alexander Laing, of Newburgh-on-Tay.

D. 'Lord Lovel,' Kinloch Manuscripts, VII, 83; Kinloch's Ancient Scottish Ballads, p. 31.

E. Communicated by Mr. J.F. Campbell, of Islay, as learned about 1850.

F. 'Lord Lovel,' communicated by Mr. Robert White, of Newcastle-on-Tyne.

G. 'Lord Revel,' Harris Manuscript, fol. 28 b.

H. 'Lord Lovel.'

a. Broadside in Dixon's Ancient Poems, Ballads and Songs of the Peasantry of England, p. 78, Percy Society, vol. xix.

b. Davidson's Universal Melodist, I, 148.

I. Percy Papers, communicated by Principal Robertson.

J. Communicated by Mr. Macmath, as derived from his aunt, Miss Jane Webster, who learned it from her mother, Janet Spark, Kirkcudbrightshire. [Child met collaborator William MacMath in 1873; the version in this addition was published in 1886. This fragment can be traced circa early 1800s; Macmath was born in 1844.]

I is made up of portions of several ballads. The first stanza is derived from 'Sweet William's Ghost,' the second and third possibly from some form of 'Death and the Lady,' 4-11 from 'Lady Maisry.' The eighth stanza of E should, perhaps, be considered as taken from 'Lord Thomas and Fair Annet,' since in no other copy of 'Lord Lovel' and in none of 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William ' does the hero die by his own hand.

In 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William,' as also in 'Lord Thomas and Fair Annet,' a lover sacrifices his inclination to make a marriage of interest. In 'Lord Lovel' the woman dies, not of affection betrayed, but of hope too long deferred, and her laggard but not unfaithful lover sinks under his remorse and grief. 'Lord Lovel ' is peculiarly such a ballad as Orsino likes and praises: it is silly sooth, like the old age. Therefore a gross taste has taken pleasure in parodying it, and the same with 'Young Beichan.' But there are people in this world who are amused even with a burlesque of Othello.[1]

There are several sets of ballads, very common in Germany and in Scandinavia, which, whether they are or are not variations of the same original, at least have a great deal in common with 'Lord Lovel' and 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William.'

Of these, one which more closely resembles the English is 'Der Ritter und die Maid,' of German origin, but found also further north.[2]

A knight and maid have been together till morning. She weeps; he tells her that he will pay for her honor, will give her an underling and money. She will have none but him, and will go home to her mother. The mother, on seeing her, asks why her gown is long behind and short before, and offers her meat and drink. The daughter refuses them, goes to bed, and dies. So far there is no dallying with the innocence of love, as in the English ballad; the German knight is simply a brutal man of pleasure. But now the knight has a dream, as in 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William;' it is that his love has died. He bids his squire or groom to saddle, and rides to find out what has happened. On his way he hears an ominous bell; further on he sees a grave digging; then he meets men carrying a bier. Set down the bier, he cries, that I may see my love. He turns back the cloth and looks at the dead. She has suffered for him, he will suffer for her. He draws his sword and runs it through his heart. They are buried in one coffin, or in the same grave. In some of the ballads lilies rise from the grave; in a Swedish version ('Jungfruns död '), a linden, the leaves of which intermingle.

Next to this we may put a Norwegian and a Swedish ballad, which, having perhaps lost something at the beginning, cannot safely be classed: 'Maarstíg aa hass möy,' Bugge, p. 127, No 26, A, B; 'Herr Malmstens dröm,' Afzelius, III, 104, No 85. Maarstíg dreams that his love's gold ring has got upon another finger, that her gold belt is off her lithe waist, her cloak or her hair is cut to bits, her shoes are full of blood; Malmsten that his love's heart breaks. The pages are ordered to saddle, and Maarstíg, or Malmsten, fides to find what there is in the dream. Maarstíg encounters two maids, who are just from a wake. "Who is dead?" "Maalfrí, thy sweet love." He rides on, meets the bier, bids the bearers set it down, and looks at the dead. Let them dig the grave, he cries, wide and deep, it shall be his bride-house; let them dig the grave deep and long, that is where bride and bridegroom shall go. He sets his sword against a stone, and falls on it. With slight variations, the course of the story is the same for Malmsten. Another Swedish ballad, 'Den sörjande,' Djurklou, p. 106, No 7, lacks even so much introduction as the dream. The lover orders his horse, hears the funeral bell, sees the grave-digging, meets the bier, looks at his dead mistress, and kills himself. A fragment in Dybeck's Runa, 1845, p. 15, begins with the ride and stops short of the death.

These last ballads apparently give us the middle and end of a story which has also some sort of beginning in the following: Danish, 'Den elskedes Død,' Kristensen, II, 39, No 20, A-D, and in many unprinted copies from oral tradition, besides two from Manuscripts of the sixteenth century, communicated to me by Grundtvig; Swedish, 'Hertig Nils,' Arwidsson, II, 21, No 72, 'Peder Palleson,' Arwidsson, No 71, II, 18, 437; Norwegian, 'Herr Stragi,' Landstad, p. 537, No 61.[3] A lover and his mistress have parted, have been long parted. She is sick, dying, or even dead. In the Danish manuscript copies we are distinctly told that she has grieved herself to death on his account. Word is sent him by carrier-pigeons, a bird, a page; or he is informed by a spae-wife (Landstad). He leaps over the table, spilling mead and wine (Kristensen), and rides faster than the doves fly. The rest of the tale is much as before, with those minor diversities that are to be expected. The lover commonly kills himself, but dies of heart-break in 'Peder Palleson' and one of the sixteenth century Danish copies. In the latter he hears the bells, says he shall never arrive alive, dies without the house and she within; in the former the maid dies in the upper room, the swain on the wild moor. In the Danish manuscript copies the man is laid south in the churchyard, the maid north [west, east], two roses spring from their breasts and span the church-roof, and there they shall stay till doom; in Kristensen it is two lilies, in Arwidsson a linden.

With these last may belong a German ballad of a young Markgraf, who marries a very young wife, goes for her mother upon the approach of a threatening childbirth, and, returning, has encounters similar to those in 'Der Ritter und die Maid.' In some instances it is a Reiter, or Jager, "wohlgemuth," not married, or in secret relations with his love, who, coming to a wood or heath, hears a bell that alarms him; etc. In the end he generally kills himself, sometimes dies of a broken heart. Lilies in several cases rise from the young woman's grave, or their grave.[4]

A Romaic ballad has the characteristic features of the English, German, and Scandinavian stories, with a beginning of its own, as these also have: 'Η Εὐγενοῦλα,' 'Ο Χάρος καἰ ἡ Κόρη,' etc. (1) Zambelios, p. 715, 2 = Passow, No 415; (2) Passow, No 418; (3) Fauriel, p. 112, No 6 = Passow, No 417; (4) Marcellus, II, 72 = Passow, No 414; (5) Chasiotis, p. 169, No 5; (6) Passow, No 416; (7) Arabantinos, p. 285, No 472; (8) Tommaseo, III, 307 f; (9) Jeannaraki, p. 239, No 301; and no doubt elsewhere, for the ballad is a favorite. A young girl, who has nine brothers and is betrothed (or perhaps newly married) to a rich pallikar, professes not to fear Death. Death immediately shows his power over her. Her lover, coming with a splendid train to celebrate his nuptials, sees a cross on her mother's gate, a sign that some one has died. In (2) he lifts a gold handkerchief from the face of the dead, and sees that it is his beloved. Or he finds a man digging a grave, and asks for whom the grave is, and is told. "Make the grave deep and broad," he cries; "make it for two," and stabs himself with his dagger. A clump of reeds springs from one of the lovers, a cypress [lemon-tree] from the other, which bend one towards the other and kiss whenever a strong breeze blows.[5]

In a Catalan ballad, a young man hears funeral bells, asks for whom they ring, is told that it is for his love, rides to her house, finds the balcony hung with black, kneels at the feet of the dead, and uncovers her face. She speaks and tells him where his gifts to her may be found, then bids him order the carpenter to make a coffin large enough for two. He draws his dagger and stabs himself; there are two dead in one house! 'La mort de la Nuvia,' Briz y Candi, I, 135, Milá, Romancerillo, p. 321 f, No 337 A 11, B 11; found also in Majorca.

As will readily be supposed, some of the incidents of this series of ballads are found in traditional song in various connections.

D is translated by Grundtvig, Engelske og skotske Folkeviser, p. 194, No 29; by Rose Warrens, Schottische Volkslieder der Vorzeit, p. 115, No 25.

Footnotes:

1. It can scarcely be too often repeated that such ballads as this were meant only to be sung, not at all to be recited. As has been well remarked of a corresponding Norwegian ballad, 'Lord Lovel' is especially one of those which, for their due effect, require the support of a melody, and almost equally the comment of a burden. No burden is preserved in the case of 'Lord Lovel,' but we are not to infer that there never was one. The burden, which is at least as important as the instrumental accompaniment of modern songs, sometimes, in these little tragedies, foreshadows calamity from the outset, sometimes, as in the Norwegian ballad referred to, is a cheerful-sounding formula, which in the upshot enhances by contrast the gloom of the conclusion. "A simple but life-like story, supported by the burden and the air, these are the means by which such old romances seek to produce an impression:" Landstad, to 'Herr Stragi,' p. 541.

2. (1), 'Das Lied vom Herren und der Magd,' 1771, Düntzer u. Herder, Briefe Goethe's an Herder, I, 157. (2), 'Eyn klegliche Mordgeschicht, von ey'm Graven vunde eyner Meyd,' Nicolai, Eyn feyner kleyner Almanach, 1777, I, 39, No 2; with variations, Kretzschmer, I, 89, No 54, Uhland, p. 220, No 97 A. (3), 'Der Ritter und das Mägdlein,' Erk, Liederhort, p. 81, No 26, a traditional variety of (2). (4), Wunderhorn, 1806, I, 50 = Erlach, II, 531, Mittler, No 91. (5), 'Des Prinzen Reue,' Meinert, p. 218, 1817. (6), Alemannia, II, 185, after a manuscript of von Arnim. (7), Erk's edition of the Wunderhorn, IV, 304. (8), Hoffmann u. Richter, Schlesische Volkslieder, p. 9, No 4. (9), Erk u. Irmer, IV, 62, No 56. (10), 'Zu späte Reue,' Fiedler, p. 161. (11), 'Der Erbgraf,' Simrock, p. 33, No 12, compounded, but partly oral. (12), 'Der Ritter und seine Dame," Pröhle, p. 19, No 13. (13), Meier, p. 316, No 177. (14-16), Ditfurth, II, 4-8, Nos 6, 7, 8. (17-22), Wagner, in Deutsches Museum, 1862, II, 758-68. (23), 'Der Herr und seine Dame,' Peter, I, 193, No 10. (24), Parisius, p. 33, No 10. (25), Adam Wolf, p. 11, No 6. (26), Alfred Müller, p. 98. (27), 'Die traurige Begegnung,' Paudler, p. 21, No 13.

Scandinavian, from the German: 'Ungersvennens Dröm,' Fagerlund, Anteckningar, p. 196; 'Jungfruns död,' Wigström, Folkdiktning, I, 52; and besides these Swedish copies, a Danish broadside, from the beginning of this century, which is very common. 'Stolten Hellelille,' "Tragica, No 22," 1657, Danske Viser, III, 184, No 130 (translated by Prior, III, 214), a somewhat artificial piece, has the outline of 'Der Ritter u. die Maid,' and is a hundred years older than any known copy of the German ballad.

A Wendish ballad, founded on the German, is very like (4): Haupt and Schmaler, I, 139, No 136.

A Dutch ballad, in the Antwerpener Liederbuch, No 45, Hoffmann, Niederländische Volkslieder, p. 61, No 15, Willems, p. 154, No 60, Uhland, No 97 B, has some points of the above, but is a very different story.

3. There is a Finnish form of this ballad, probably derived from the Swedish; also another Swedish version in Westergötlands Fornminnesförenings Tidskrift, 1869, häfte 1, which I have not yet seen.

4. (1), "Bothe, Frühlings-Almanach," p. 132, 1806; 'Hans Markgraf,' Büsching u. von der Hagen, p. 30; Erlach, II, 136; Mittler, No 133. (2), 'Alle bei Gott die sich lieben,' Wunderhorn, II, 250, 1808, Mittler, No 128. (3), 'Alle bei Gott die sich lieben,' Hoffmann u. Richter, p. 12, No 5, Mittler, No 132. (4), 'Der Graf u. die Bauerntochter,' Ditfurth, II, 8, No 9. (5), 'Vom jungen Markgrafen,' Pogatschnigg u. Hermann, II, 179, No 595. (6), 'Die junge Mutter,' Paudler, p. 22, No 14.

(7), 'Jungfer Dörtchen ist todt,' Parisius, p. 36, No 10. (8), 'Liebchens Tod,' Erk u. Inner, VI, 4, No 2; Mittler, No 130. (9), 'Jägers Trauer,' Pröhle, p. 86, No 57; Mittler, No 129. (10), 'Das unverdiente Kränzlein,' Meinert, p. 32; Mittler, No 131. For plants springing from lovers' graves, as here and in Nos 73, 74, see vol. i, 96 ff.

5. In (2) the lover is warned of mishap by a bird, and the bird is a nightingale, as in Kristensen, II, No 20 A. A bird of some sort figures in all the Danish ballads referred to, printed and unprinted, and in the Swedish 'Hertig Nils;' also in the corresponding Finnish ballad. The nightingale warns to the same effect in a French ballad, Beaurepaire, p. 52. The lover goes straight to his mistress's house, and learns that they are burying her; then makes for the cemetery, hears the bells, the priests chanting, etc., and approaches the bier. The dead gives him some information, followed by some admonition.

Brief Description by George Lyman Kittredge

In 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William' (No. 74). as also in 'Lord Thomas and Fair Annet' (No. 73), a lover sacrifices his inclination to make a marriage of interest. In 'Lord Lovel' the woman dies, not of affections betrayed, but of hopes too long deferred, and her laggard but not unfaithful lover sinks under his remorse and grief. There are several sets of ballads, very common in Germany and in Scandinavia, which, whether they are or are not variations of the same original, at least have a great deal in common with 'Lord Lovel' and 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William.' Of these, one which more closely resembles the English is 'Der Ritter und die Maid,' of German origin (see Uhland, No. 97; Erk, Liederhort, No. 26), but found also in Scandinavia. A Romaic ballad (Passow, No. 415) has the characteristic features of the English, German, and Scandinavian stories, with a beginning of its own, as these also have.

Child's Ballad Texts

'Lady Ouncebell'- Version A; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Percy Papers, communicated by the Rev. P. Parsons, of Wye, from singing; May 22, 1770, and April 19, 1775.

1 'And I fare you well, Lady Ouncebell,

For I must needs be gone,

And this time two year I'll meet you again,

To finish the loves we begun.'

2 'That is a long time, Lord Lovill,' said she,

'To live in fair Scotland;'

'And so it is, Lady Ouncebell,

To leave a fair lady alone.'

3 He had not been in fair Scotland

Not half above half a year,

But a longin mind came into his head,

Lady Ouncebell he woud go see her.

4 He called up his stable-groom,

To sadle his milk-white stead;

Dey down, dey down, dey down dery down,

I wish Lord Lovill good speed.

5 He had not been in fair London

Not half above half a day,

But he heard the bells of the high chapel ring,

They rang with a ceserera.

6 He asked of a gentleman,

That set there all alone,

What made the bells of the high chapel ring,

The ladys make all their moan.

7 'One of the king's daughters are dead,' said he,

'Lady Ouncebell was her name;

She died for love of a courtous young night,

Lord Lovill he was the same.'

8 He caused her corps to be set down,

And her winding sheet undone,

And he made a vow before them all

He'd never kiss wowman again.

9 Lady Ouncebell died on the yesterday,

Lord Lovill on the morrow;

Lady Ouncebell died for pure true love,

Lord Lovill died for sorrow.

10 Lady Ouncebell was buried in the high chancel,

Lord Lovill in the choir;

Lady Ouncebell's breast sprung out a sweet rose,

Lord Lovill's a bunch of sweet brier.

11 They grew till they grew to the top of the church,

And then they could grow no higher;

They grew till they grew to a true-lover's not,

And then they tyed both together.

12 An old wowman coming by that way,

And a blessing she did crave,

To cut of a bunch of that true-lover's not,

And buried them both in one grave.

-------------

'Lord Lavel'- Version B; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Kinloch Manuscripts, I, 45, from the recitation of Mary Barr, of Lesmahago, " aged upwards of 70," May, 1827.

1 Lord Lavel he stands at his stable-door,

Kaiming his milk-white steed;

And by and cam Fair Nancybelle,

And wished Lord Lavel good speed.

2 'O whare are ye going, Lord Lavel?' she said,

'I pray ye tell to me:'

'O I am going to merry England,

To win your love aff me.'

3 'And when will ye return again?' she said,

'Lord Lavel, pray tell to me:'

'Whan seven lang years are past and gane,

Fair Nancybelle, I'll return to thee.'

4 ''Tis too lang, Lord Lavel,' she said,

''Tis too lang for me;

'Tis too long, Lord Lavel,' she said,

'A true lover for to see.'

* * * * *

5 He had na been in merry England

A month but barely three,

Till languishing thoughts cam into his mind,

And Nancybelle fain wad he see.

6 He rade, and he rade, alang the hieway,

Till he cam to yonder toun;

He heard the sound o a fine chapel-bell,

And the ladies were mourning roun.

7 He rade, and he rade, alang the hieway,

Till he cam to yonder hall;

He heard the sound o a fine chapel-bell,

And the ladies were mourning all.

8 He asked wha it was that was dead,

The ladies did him tell:

They said, It is the king's daughter,

Her name is Fair Nancybelle;

She died for the love of a courteous young knicht,

His name is Lord Lavel.

9 'O hast thou died, Fair Nancybelle,

O hast thou died for me!

O hast thou died, Fair Nancybelle!

Then I will die for thee.'

10 Fair Nancybelle died, as it might be, this day,

Lord Lavel he died tomorrow;

Fair Nancybelle died with pure, pure love,

Lord Lavel he died with sorrow.

11 Lord Lavel was buried in Mary's kirk,

Nancybelle in Mary's quire;

And out o the ane there grew a birk,

Out the other a bonny brier.

12 And ae they grew, and ae they threw,

Until they twa did meet,

That ilka ane might plainly see

They war twa lovers sweet.

-----------

'Lord Travell'- Version C; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Communicated by Mr. Alexander Laing, 1873, as taken down from the recitation of Miss Fanny Walker, of Mount Pleasant, near Newburgh-on-Tay.

1 Lord Travell stands in his stable-door,

Dressing his milk-white steed,

An bye comes Lady Ounceville:

'I wish you muckle speed.

2 'Oh whar are ye gaun, Lord Travell?' she says,

'Whar are gaun frae me?'

'I am gaun to London town,

Some strange things for to see.'

3 'Whan will ye be back, Lord Travell?' she says,

'Whan will ye be back to me?'

'I will be back in seven lang years,

To wed my gay ladie.'

4 'Oh that is too lang for me,' she says,

'Oh that is too lang for me;

Oh that is too lang for me,' she says,

'To wed thy gay ladie.'

5 He hadna been in London town

A week but only three,

When a boding voice thirld in his ear,

That Scotland he maun see.

6 He rade an he rode alang the highway,

Till he cam to yon little town:

'Oh is there ony body dead?

The bells they mak sic a sound.'

7 He rade an he rode alang the highway,

Till he cam to yon little town:

'Oh is there ony body dead?

The folk gae mournin round.'

8 'Oh yes indeed, there is ane dead,

Her name is Ounceville;

An she has died for a courteous knicht,

His name is Lord Travell.'

9 'Oh hand ye aboot, ye gentlemen,

The white bread an the wine,

For the morn's nicht aboot this time

Ye'll do the same for mine!'

-----------

'Lord Lovel'- Version D; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Kinloch Manuscripts, VII, 83, from the recitation of a lady of Roxburghshire; Kinloch 's Ancient Scottish Ballads, p. 31.

1 Lord Lovel stands at his stable-door,

Mounted upon a grey steed,

And bye cam Ladie Nanciebel,

And wishd Lord Lovel much speed.

2 'O whare are ye going, Lord Lovel?

My dearest, tell unto me:'

'I am going a far journey,

Some strange countrey to see.

3 'But I'll return in seven long years,

Lady Nanciebel to see:'

'Oh seven, seven, seven long years,

They are much too long for me.'

* * * * *

4 He was gane about a year away,

A year but barely ane,

Whan a strange fancy cam intil his head

That faire Nanciebel was gane.

5 It's then he rade, and better rade,

Untill he cam to the toun,

And there he heard a dismal noise,

For the church bells au did soun.

6 He asked what the bells rang for;

They said, It's for Nanciebel;

She died for a discourteous squire,

And his name is Lord Lovel.

7 The lid of the coffin he opened up,

The linens he faulded doun,

And ae he kissd her pale, pale lips,

And the tears cam trinkling doun.

8 'Weill may I kiss these pale, pale lips,

For they will never kiss me;

I'll mak a vow, and I'll keep it true,

That I'll neer kiss ane but thee.'

9 Lady Nancie died on Tuesday's nicht,

Lord Lovel upon the niest day;

Lady Nancie died for pure, pure love,

Lord Lovel for deep sorraye.

-----------

['Lord Lovel']- Version E; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Communicated by J.F. Campbell, Esq., as learned from the singing of an English gentleman, about 1850.

1 'Now fare ye well, Lady Oonzabel,

For I must needs be gone,

To visit the king of fair Scotland,

Oh I must be up and ride.'

2 So he called unto him his little foot-page,

To saddle his milk-white steed;

Hey down, hey down, hey derry, hey down,

How I wish my Lord Lovel good speed!

3 He had not been in fair Scotland,

Not passing half a year,

When a lover-like thought came into his head,

Lady Oonzabel he would go see her.

4 So he called unto him his little foot-page,

To saddle his milk-white steed;

Hey down, hey down, hey derry, hey down,

How I wish my Lord Lovel good speed.

5 He had not been in fair England,

Not passing half a day,

When the bells of the high chappel did ring,

And they made a loud sassaray.

6 He asked of an old gentleman

Who was sitting there all alone,

Why the bells of the high chappel did ring,

And the ladies were making a moan.

7 'Oh, the king's fair daughter is dead,' said he;

'Her name's Lady Oonzabel;

And she died for the love of a courteous young knight,

And his name it is Lord Lovel.'

* * * * *

8 He caused the bier to be set down,

The winding sheet undone,

And drawing forth his rapier bright,

Through his own true heart did it run.

9 Lady Oonzabel lies in the high chappel,

Lord Lovel he lies in the quier;

And out of the one there grew up a white rose,

And out of the other a brier.

10 And they grew, and they grew, to the high chappel top;

They could not well grow any higher;

And they twined into a true lover's knot,

So in death they are joined together.

-----------

'Lord Lovel'- Version F; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Communicated by Mr. Robert White, of Newcastle-on-Tyne.

1 As Lord Lovel was at the stable-door,

Mounting his milk-white steed,

Who came by but poor Nancy Bell,

And she wished Lovel good speed.

2 'O where are ye going, Lord Lovel?' she said,

'How long to tarry from me?'

'Before six months are past and gone,

Again I'll return to thee.'

3 He had not been a twelvemonth away,

A twelvemonth and a day,

Till Nancy Bell grew sick and sad,

She pined and witherd away.

4 The very first town that he came to,

He heard the death-bell knell;

The very next town that he came to,

They said it was Nancy Bell.

5 He orderd the coffin to be broke open,

The sheet to be turned down,

And then he kissd her cold pale lips,

Till the tears ran tricklin down.

6 The one was buried in St. John's church,

The other in the choir;

From Nancy Bell sprang a bonny red rose,

From Lord Lovel a bonny briar.

7 They grew, and they grew, to the height o the church,

To they met from either side,

And at the top a true lover's knot

Shows that one for the other had died.

-------------

'Lord Revel'- Version G; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Harris Manuscript, fol. 28 b, from the recitation of Mrs. Molison, Dunlappie.

1 Lord Revel he stands in his stable-door,

He was dressing a milk-white steed;

A lady she stands in her bour-door,

A dressin with haste an speed.

2 'O where are you goin, Lord Revel,' she said,

'Where are you going from me?'

'It's I am going to Lonnon toun,

That fair city for to see.'

3 'When will you be back, Lord Revel?' she said,

'When will you be back to me?'

'I will be back in the space of three years,

To wed you, my gey ladie.'

4 'That's too long a time for me,' she said,

'That's too long a time for me;

For I'll be dead long time ere that,

For want of your sweet companie.'

5 He had not been in Lonnon toun

A month but barely three,

When word was brought that Isabell

Was sick, an like to dee.

6 He had not been in Lonnon toun

A year but barely ane,

When word was brought from Lonnon toun

That Isabell was gane.

7 He rode an he rode along the high way,

Till he came to Edenborrow toon:

Is there any fair lady dead,' said he,

'That the bells gie such a tone?'

8 'Oh yes, there's a ladie, a very fine ladie,

Her name it is Isabell;

She died for the sake of a young Scottish knight,

His name it is Lord Revel.'

9 'Deal well, deal well at Isabell's burial

The biscuit and the beer,

An gainst the morrow at this same time

You'll aye deal mair and mair.

10 'Deal well, deal well at Isabell's burial

The white bread and the wine,

An gainst the morn at this same time

You'll deal the same at mine.'

11 They dealt well, dealt weel at Isabell's burial

The biscuit an the beer,

And gainst the morn at that same time

They dealt them mair an mair.

12 They dealt weel, dealt weel at Isabell's burial

The white bread an the wine,

An gainst the morn at that same time

They dealt the same again.

-------------

'Lord Lovel'- Version H; Child 75 Lord Lovel

a. London broadside of 1846, in Dixon's Ancient Poems, Ballads, and Songs of the Peasantry of England, p. 78, Percy Society, vol. xix.

b. Davidson's Universal Melodist, I, 148.

1 Lord Lovel he stood at his castle-gate,

Combing his milk-white steed,

When up came Lady Nancy Belle,

To wish her lover good speed, speed,

To wish her lover good speed.

2 'Where are you going, Lord Lovel?' she said,

'Oh where are you going?' said she;

'I'm going, my Lady Nancy Belle,

Strange countries for to see.'

3 'When will you be back, Lord Lovel?' she said,

'Oh when will you come back?' said she;

'In a year or two, or three, at the most,

I'll return to my fair Nancy.'

4 But he had not been gone a year and a day,

Strange countries for to see,

When languishing thoughts came into his head,

Lady Nancy Belle he would go see.

5 So he rode, and he rode, on his milk-white steed,

Till he came to London town,

And there he heard St Pancras bells,

And the people all mourning round.

6 'Oh what is the matter?' Lord Lovel he said,

'Oh what is the matter?' said he;

'A lord's lady is dead,' a woman replied,

'And some call her Lady Nancy.'

7 So he ordered the grave to be opened wide,

And the shroud he turned down,

And there he kissed her clay-cold lips,

Till the tears came trickling down.

8 Lady Nancy she died, as it might be, today,

Lord Lovel he died as tomorrow;

Lady Nancy she died out of pure, pure grief,

Lord Lovel he died out of sorrow.

9 Lady Nancy was laid in St. Pancras church,

Lord Lovel was laid in the choir;

And out of her bosom there grew a red rose,

And out of her lover's a briar.

10 They grew, and they grew, to the church-steeple too,

And then they could grow no higher;

So there they entwined in a true-lover's knot,

For all lovers true to admire.

-----------

['Fair Helen'] Version I; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Percy Papers, communicated by Principal Robertson, the historian.

1 There came a ghost to Helen's bower,

Wi monny a sigh and groan:

'O make yourself ready, at Wednesday at een,

Fair Helen, you must be gone.'

2 'O gay Death, O gallant Death,

Will you spare my life sae lang

Untill I send to merry Primrose,

Bid my dear lord come hame?'

3 'O gay Helen, O galant Helen,

I winna spare you sae lang;

But make yoursell ready, again Wednesday at een,

Fair Helen, you must be gane.'

4 'O where will I get a bonny boy,

That would win hose and shoon,

That will rin fast to merry Primrose,

Bid my dear lord come soon?'

5 O up and speak a little boy,

That would win hose and shoon:

'Aft have I gane your errants, lady,

But by my suth I'll rin.'

6 When he came to broken briggs

He bent his bow and swam,

And when he came to grass growing

He cast off his shoon and ran.

7 When he came to merry Primrose,

His lord he was at meat:

'O my lord, kend ye what I ken,

Right little wad ye eat.'

8 'Is there onny of my castles broken doun,

Or onny of my towers won?

Or is Fair Helen brought to bed

Of a doughter or a son?'

9 'There's nane of [your] castles broken doun,

Nor nane of your towers won,

Nor is Fair Helen brought to bed

Of a doghter or a son.'

10 'Gar sadle me the black, black steed,

Gar sadle me the brown;

Gar sadle me the swiftest horse

Eer carried man to town.'

11 First he bursted the bonny black,

And then he bursted the brown,

And then he bursted the swiftest steed

Eer carried man to town.

12 He hadna ridden a mile, a mile,

A mile but barelins ten,

When he met four and twenty gallant knights,

carrying a dead coffin.

13 'Set down, set down Fair Helen's corps,

Let me look on the dead;'

And out he took a little pen-knife,

And he screeded the winding-sheet.

14 O first he kist her rosy cheek,

And then he kist her chin,

And then he kist her coral lips,

But there's nae life in within.

15 'Gar deal, gar deal the bread,' he says,

'The bread bat an the wine,

And at the morn at twelve o'clock

Ye's gain as much at mine.'

16 The tane was buried in Mary's kirk,

The tother in Mary's choir,

And out of the tane there sprang a birch,

And out of the tother a briar.

17 The tops of them grew far sundry,

But the roots of them grew neer,

And ye may easy ken by that

They were twa lovers dear.

-----------

'Lord Lovel'- Version J; Child 75 Lord Lovel

Communicated by Mr. Macmath, as derived from his aunt, Miss Jane Webster, who learned it from her mother, Janet Spark, Kirkcudbrightshire.

1 Lord Lovel was standing at his stable-door,

Kaiming down his milk-white steed,

When by came Lady Anzibel,

Was wishing Lord Lovel good speed, good speed,

Was wishing Lord Lovel good speed.

2 'O where are you going, Lord Lovel?' she said,

'O where are you going?' said she:

'I'm going unto England,

And there a fair lady to see.'

3 'How long will you stay, Lord Lovel?' she said,

'How long will you stay?' says she:

'O three short years will soon go by,

And then I'll come back to thee.'

End-Notes

Lord Lovel

A. The copy sent Percy in 1770 was slightly revised by Parsons; the original was communicated in 1775.

33. along in.

44. coud speed.

63. make.

64. their mourn.

104. Parsons corrects bunch to branch.

G. 74. bell.

H. a. 101. church-steeple too, perhaps a misprint for top.

b. This is an attempt to burlesque the broad-side by vulgarizing two or three words, as lovier, buzzum, and inserting one stanza.

24, 42. Foreign countries.

33. In a year, or two or three, or four.

41. twelve months and a day.

63. dead, the people all said.

72. to be turned.

74. Whilst.

After 7:

Then he flung his self down by the side of the corpse,

With a shivering gulp and a guggle;

Gave two hops, three kicks, heavd a sigh, blew his nose,

Sung a song, and then died in the struggle.

101. church-steeple top.

102. they twin'd themselves into.

I. 32. 'you,' as if changed or supplied.

52. Crossed out. In a different hand, Just at the lady's chin.

74. would wad ye.

113. swifted.

134. Perhaps scrieded.

Additions and Corrections

204 and 212: Add version J.

J. Communicated by Mr. Macmath, as derived from his aunt, Miss Jane Webster, who learned it from her mother, Janet Spark, Kirkcudbrightshire. [Child met collaborator William MacMath in 1873; the version in this addition was published in 1886. This fragment can be traced circa early 1800s; Macmath was born in 1844.]

1 Lord Lovel was standing at his stable-door,

Kaiming down his milk-white steed,

When by came Lady Anzibel,

Was wishing Lord Lovel good speed, good speed,

Was wishing Lord Lovel good speed.

2 'O where are you going, Lord Lovel?' she said,

'O where are you going?' said she:

'I'm going unto England,

And there a fair lady to see.'

3 'How long will you stay, Lord Lovel?' she said,

'How long will you stay?' says she:

'O three short years will soon go by,

And then I'll come back to thee.'

P. 205 a, note †. Add: (28) a copy in B. Seuffert, Maler Müller, Berlin, 1877, p. 455 f: R. Köhler. (Dropped in the second edition, 1881.)

205 b, note *. The Finnish version is 'Morsiamen kuolo,' Kanteletar, 1864, p. viii.

P.206. Add: Decombe, 'Derrier' la Trinité,' p. 210, No 75, 'En chevauchant mon cheval rouge,' p. 212, No 76; Ampère, Instructions, p. 36, Bulletin du Comité, etc" I, 252, 'Les chevaux rouges.'

P. 205 b. Other copies of 'Den elskedes Død' ('Kjærestens Død'), Kristensen, Skattegraveren, VII, 1, 2, Nos 1, 2; Bergström ock Nordlander, in Nyare Bidrag, o.s.v., pp. 92, 100; and 'Olof Adelen,' p. 98, may be added, in which a linden grows from the common grave, with two boughs which embrace.

Note. With the Scandinavian-German ballads belongs 'Greven og lille Lise,' Kristensen, Skattegraveren, V, 20, No 14.

206, 512 b. To the southern ballads which have a partial resemblance may be added: French, Beaurepaire, p. 52, Combes, Chants p. du Pays castrais, p. 139, Arbaud, I, 117, Victor Smith, Romania, VII, 83, No. 32; Italian, Nigra, 'La Sposa morta,' No 17, p. 120 ff. (especially D).

215. I ought not to have omitted the #963;ήματα by which Ulysses convinces Penelope, Odyssey, xxiii, 181-208; to which might be added those which convince Laertes, xxiv, 328 ff. See also the romance of Don Bueso, Duran, I, lxv:

¿Qué señas me dabas

Por ser conocida? et cét.

P. 204 f., note †, 512 b. Add: Hruschka u. Toischer, Deutsche V. 1. aus Böhmen, p. 108, No 20, a-f.

205 a, note, III, 510 b. For 'Stolten Hellelille, see Danmarks gamle Folkeviser, V, II, 352, No 312, 'Gøde og Hillelille.' Add: 'Greven og lille Lise,' Kristensen, Jyske Folkeminder, X, 319, No 79, A-E.

205 b, III, 510 b. 'Den elskedes Død:' the same volume of Kristensen, 'Herr Peders Kjæreste,' p. 327, No 80.

206, 512 b, III, 510 b. 'Lou Fil del Rey et sa Mio morto,' Daymard, Vieux Chants p. rec. en Quercy, p. 82.

There is a similar ballad, ending with admonition from the dead mistress, in Luzel, Soniou, I, 324, 25, 'Cloaregic ar Stanc.'

P. 204 f., note †, 512 b, IV 471 a. Add 'Der Graf und das Mädchen,' Böckel, Deutsche V.-l. aus Oberhessen, p. 5, No 6; 'Es schlief ein Graf bei seiner Magd,' Lewalter, Deutsche V.-l. in Niederhessen gesammelt, 2s Heft, p. 3, No 2: 'Der Graf und sein Liebchen,' Frischbier u. Sembrzycki, Hundert Ostpreussische Volkslieder, p. 34, No 21.

205 a, note, III, 510 b, IV, 471 b. Scandinavian, Other copies of 'Lille Lise,' 'Greven og lille Lise,' Kristensen, Efterslæt til Skattegraveren, p. 18, No 15, Folkeminder, XI, 159, No 62, A-D.

205. 'Den elskedes Død,' Berggreen, Danske Folkesange, 3d ed., p. 162, No 80 b; Svenske Fs., 2d ed., p. 84, No 66 b.

The ballad exists in Esthonian: Kaarle Krohn, Die geographische Verbreitung estnischer Lieder, p. 23.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

P. 204 f., note †, 512 b, IV, 471 a, V, 225 a. Add: Wolfram, p. 87, No 61, 'Es spielte ein Ritter mit einer Madam.'

205 b, note *. The Swedish ballad (p. 71 f. of the publication mentioned) is defective at the end, and altogether amounts to very little.

[206. Romaic. Add: 'La belle Augiranouda,' Georgeakis et Pineau, Folk-lore de Lesbos, p. 223 f.]

206 a, and note *. Add: Wolfram, No 28, p. 55, 'Es war ein Jäger wohlgemut,' and 'Jungfer Dörtchen,' Blätter für Pommersche Volkskunde, II. Jahrgang, p. 12.

211, H. I have received a copy recited by a lady in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which was evidently derived from print, and differs but slightly from a, omitting 83,4, 91,2.