No. 74: Fair Margaret and Sweet William

[As noted by several early scholars and collectors (Percy, Jamieson, etc) there is an affinity between Child No. 73, Lord Thomas and Child No. 74. Fair Margaret and Sweet William. In some versions the brown girl is again mentioned as Sweet William's bride. It's almost as if Child 74 was a sequel or parallel ballad with a different ending. Suppose the brown girl married Sweet Willie (Lord Thomas) as in Child 73 but Fair Ellender (Sweet Annie/Annet) who is now Fair Margaret does not come to the wedding, instead she stays home and sees her love Sweet Willie (Lord Thomas) walking with the brown girl from her bower window. Fair Ellinor (Fair Margaret) throws down her ivory comb and ballad No. 74 continues to its fatal conclusion.

Some of the stanzas between No. 73 and 74 are interchangeable and again, the two true lovers do not marry, a situation that happens in life as well as ballads.

Perhaps the variant that most clearly shows the interaction between Child 73 and 74 is the ballad collected by Grieg as sung by Mrs. Dunbar, who learned it from her grandmother. This resembles the Scottish variants of Child 73 with Willie and Annie. It begins as child 73, and after the wedding the brown girl and Willie go to sleep. Then Annie's ghost appears at his bed-feet. The ballad continues as Child 74.

"Sweet Willie and Fair Annie" - Greig MS, IV, p. 26; text, Bk. 761, LI, p. 101. Sung by Mrs. Dunbar; learned from her grandmother.

1. What think ye, O father dear,

Has Willie slighted me;

He bids me come to his marriage

And nae his bride to be.

2. It's I've as mony men in my smiddy, Annie

As wad buy a weed to thee;

It sanna be o' the dowie black,

Nor yet o' the dowie grey;

But it sall be o' the scarlet red

And ye'll wear it daily day.

3. Annie gaed in the heid o' the hill,

And Willie gaed in the glen;

And Annie had mair show her lane

Than Willie and a' his men.

4. When they came to the bridal house

And a'were dighted in,

And fa was sae ready as Willie's ae sister

To welcome fair Annie in?

5. Willie's ta'en aff his hat o' silk,

And placed it on Annie's heid,-

Ye'll wear that hat yersel', Willie,

Ye'll wcar it wi' muckle glee;

Ye'll wear that hat yersel', Willie,

For ye'll never get mair o' me.

6. Oot then spak the nut-broon bride,

And she spak oot in spite,

Faur got ye the water, Annie,

That washes you sae fite?

7. I got the water in my father's garden,

Where ye will never get nane;

I got it in my father's larden

Beneath the greentree's spring.

8. But ye've been washen in dinnie's well,

And dried on dinnie's dyke;

And a' the water in the warld

Will never wash ye fite.

9. But the nut-broon may has coos and yowes,

Fair Annie she has nane;

The nut-broon may is Willie's bride,

Fair Annie maun lie her lane.

10. When-night was come & mass was sung,

And a' men bound for bed,

Willie & his nut-broon bride

Were baith in ae bed laid.

11. They had not been but weel laid doon,

Not yet weel fa'en asleep,

Till up there started Annie's ghost

Just close at their bed-feet.

12. How do you like your blankets, Willie,

Or how do you like your sheets?

Or how do you like your nut-broon bride,

So ready in your arms she sleeps.

13. Weel do I like my blankets,

And weel do I like my sheets,

But I'm afraid that Annie's ghost

It stands at my bed-feet.

14. Lie still, Willie, lie still, Willie,

Lie still this nicht wi' me;

For it's only the shadow o' Annie's glove

That glimmers in your et.

15. Some drew to them their stockin's, their stockin's

And some drew to them their shoon,

But alas for poor Willie,

And clothing he sought nane.

16. He has ta'en his licht mantle,

And he's awa to Drumhill;

And fa was sae ready as Annie's ae Sister

To welcome young Willie in.

17. Come in, Willie, come in, Willie,

And lock up a' the deid;

For red & rosy were her cheeks last nicht,

And the nicht they're but a weed.

18. He laid his heid upon his hands,

And oh, his hert grew sair;

At the morn at this same time

It's sae will ye be at mine.

19. The ane was buried in St. Mary's kirk;

And the ither in St. Mary's quire;

And oot o' the ane there grew a birk

And oot o' the ither a brier.

20. It's they grew on & they grew on,

Till they grew very near;

And every one that passed them by

Said: There lies lovers dear.

* * * *

As noted by Child (ref. Percy) the ballad was mentioned in the second act of Beaumont and Fletcher's The Knight of the Burning Pestle, 11. 476—479 (H. S. Murch's edition in Yale Studies in English; 1908):

'When it was growne to darke midnight,

And all were fast asleepe,

In came Margarets grimely Ghost,

And stood at Williams feete.'

This resembles stanza 5 of Child A and is also the basis of the composed ballad, "William and Margaret" which was claimed by David Mallet who published it in 1724. Around 150 years later Chappell found a nearly identical broadside of Mallet's ballad and accused Mallet of forgery. Chappell's claim is dependent on the date of the stamp found on the broadside "William and Margaret: An Old Ballad" which he dated as before 1711. More recent examinations of the date of the stamp (Swaen 1917) show that the 1711 date is inconclusive. Mallet's ballad itself is of little value of the study of the traditional ballad and Child says, (see below in his headnotes) " 'William and Margaret' is simply 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William' rewritten in what used to be called an elegant style." This is not quite true, since only one stanza is common to both "William and Margaret" and the traditional ballad and it (see immediately above) begins, "When it was grown to dark midnight." This single is found in Beaumont and Fletcher's The Knight of the Burning Pestle of 1611.

Also found "Burning Pestle" are these lines as sung by old Merrie-Thought as he enters. In Act III he says to his wife:

Good woman if you wil sing Il' e giue you something, if not --

"You are no loue for me Margret,

I am no loue for you.'

(11. 616 — 619, first quarto) The second folio has:

You are no love for me Margret,

I am no love for you

In his notes (1908 edition) to this passage Herbert Spencer Murch observes: "we have here two lines from some ballad now lost." These two lines fit into the second stanza of "Fair Margaret's Misfortune." What this shows is that an earlier traditional ur-ballad was present at that time (1611) that is similar to the broadside "Fair Margaret's Misfortune", which is Child A.

Chappell replaced the"Fair Margaret" lines with the "Burning Pestle" lines at the beginning of the second stanza (see, in brackets), and Chappel says:

With Old MerryThought's restoration the opening stanzas will be:

1. "'As it fell out on a long summer's day,

Two lovers they sat on a hill;

They sat together that long summer's day,

And could not talk their fill."

2. "['I am no love for you, Margaret,

And you are no love for me;]

Before to-morrow at eight o'[the]clock,

A rich wedding you shall see.'"

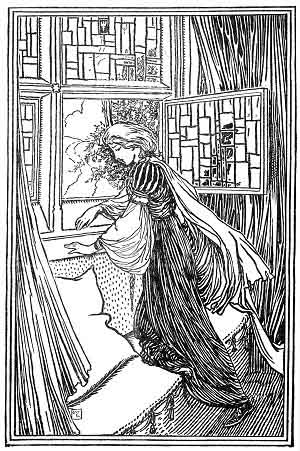

3. "Fair Margaret sate in her bower-window

A combing of her hair;

There she espied Sweet William and his bride

As they were a riding near.'"

4. "Down she laid her ivory comb.

And up she bound her hair;

She went away, forth from the bower,

But nevermore came [she] there."

5 "When day was gone, and night was come,

And all were fast asleep.

Then came the spirit of fair Margaret,

And stood at William's bed-feet."

The broadside which is based on the ur-ballad has the weaker lines for the opening of stanza 2:

2 'I see no harm by you, Margaret,

Nor you see none by me;

The last line in stanza 1 is written "take their fill" in Chappell's Publications, Volume 29 by Ballad Society; 1888. Robert Chambers; John Ashton and Frank Sidgwick also have "take." Child has "talk" as do the some of the broadsides; "take" seems to be the only proper reading of this line.

As reported in British Ballad from Maine: Twice it is quoted in Beaumont and Fletcher's Knight of the Burning Pestle-act If, sc. 8; act III, sc. 5-and we are of the opinion that in addition to the two well-known snatches so often cited there is still another reference to it in the same play, in act IV, sc. 1. where the Citizen's Wife arranges a scene in the play for her favorite

Ralph to act in:

an let him be very weary, and come to the King of Cracovia's house, covered with black velvet; and there let the king's daughter stand in her window, all in beaten gold, combing her golden locks with a comb of ivory; and let her spy Ralph and fall in love with him.

The ivory comb, the golden locks, the maid in the window, all belong to the ballad of "Fair Margaret and Sweet William," already twice quoted in the same play.

* * * *

Child A a, the broadside, is named: "Fair Margaret's Misfortune, or, Sweet William's Frightful Dreams on his Wedding Night. With the Sudden Death and Burial of those Noble Lovers." It was printed for Sarah Bates, at the Sun and Bible, in Giltspur Street and dated circa 1685 by Chappell. David Atkinson wrote a recent article "William and Margaret; An Eighteenth Century Ballad" which is largely about Mallet and follows the 1917 article by Swaen titled "Fair Margaret and Sweet William." Swaen's article is also focused on Mallet's "William and Margaret" and less on the traditional ballad represented by Child A-C.

Atkinson dates the "Fair Margaret" broadside at circa 1720. Whether it's 1685 or 1720 is immaterial to the premise that the ballad dates back to at least the early 1600s (1611 Burning Pestle). Again as in Child 73 Lord Thomas and Fair Ellinor the broadside is likely written down from a traditional ballad, the ur-ballad, which is known only through traditional ballads collected in North America and the British Isles. Because the ballad was popular in North America we can surmise that early versions that predate the broadside were brought to the Virginia settlement, New England and also Maritime Canada where it is found less frequently.

Is the broadside sung in tradition? Yes but it is rarely found in tradition as written. The traditional versions found in North America have stanzas from the broadside but also this important opening stanza,

Sweet William he rose one morning in May,

Himself he dresses in blue.

His mother asked him about that long, long love

[That] Lies between Lady Margaret and you. [Sweet William- Nora Hicks]

this stanza which is critical in establishing the relationship between Margaret and William. This stanza is common in North America and is found in Child B. The stanza that follows of course is the fragment (in brackets) from the 1611 "Burning Pestle".

["I am no love for you, Margaret,

And you are no love for me;]

Before to-morrow at eight o'clock,

A rich wedding you shall see."

The broadside's "I see no harm by you, Margaret," is similar in meaning as are a number of variant lines such as "I am no man for you" which was collected in California. This shows is William is trying to ignore his deep feelings for Margaret because he is marrying "the brown girl" and it's clear that she knows something about this relationship, because he asks his new wife's permission to see Margaret after his dream. The broadside skips the "he dressed himself in blue" stanza and with this stanza missing the ballad makes little sense afterward.

It's easy to understand that the "he dressed himself in blue" stanza would be part of the ur-ballad and that the ballad came to North America in this form. In North America the ballad is found in Canada, New England but the large repositories are found in the Appalachian region showing the ballad mainly came to the Virginia colony and spread eastward to the mountains (NC, KY WV, TN) in the late 1700s. Since the broadside is dated c.1720 it may be assumed that an earlier version resembling the ur-ballad came to North America before then with the Virignia colonists. The Virginia House of Burgess was established in 1619 in Jamestown and by 1700 their were 70,000 settlers mostly of British descent. Samuel Hicks (Hix) the progenitor of the Hicks family was born c. 1695 along the James River in what is now Goochland, Virginia. By 1760 he had moved his family to central North Carolina and his son David and grandson Samuel settled into the Beech Mountain area by 1770. The ballads were passed down through generations and Nora Hicks sang an ancient family version which likely predated the c.1720 broadside.

* * * *

Some of the titles of Child No. 7 Earl Brand (Lady Margaret) are similar to the titles of Child No. 74 (Fair Margaret). There are also versions of Child Ballad No. 77 (Sweet William's Ghost) titled, "Lady Margaret." Lydia is a variant of the word, "lady" as many versions are Lady Margaret and pronounced "Liddy" (Dew Hanson) or "Lydia." The name Margaret is not sung "Mar-ga-ret" in three syllables but is sung "Mar-gret" in two syllables. Titles or names spelled "Margret" or "Marg'ret" are simple reflection of the way the name is really sung. In some renditions the two syllable name has further deteriorated into "Margot" or "Marget."

Beside the exchange with stanzas from Child No. 73 Lord Thomas mentioned above, there is also a stanza (or stanzas) from Child No. 85 George Collins (Lady Alice) where the coffin is viewed and he kisses "her cold clay lips" that will never kiss his.

* * * *

Fair Margaret, my title for Child C, could also be titled "As Margaret Stood at her Window." I've obtained a copy of Parson's letters to Percy from the Harvard library. In his letter, Parsons calls it, "Ballad of Sweet William." Child ignores Parsons statement that the first two stanzas are the same as Percy's, renumbers them and separates stanza 6 and 7 as follows:

6 'Oh is Fair Margaret in the kitchen?

Or is she in the hall?

. . . . .

. . . .

7 'No, she is not in the kitchen,' they cryed,

'Nor is she in the hall;

But she is in the long chamber,

Laid up against the wall.'

Parsons writes:

"The Ballad of Sweet William was the same as Yours in the Stanzas I have omitted. In the 8th Stanza and 35th Line Yours runs:

To dream thy Bower was full of ‘red’ Swine, which last words are marked as of uncertain reading. I think I have restored the Original Reading. The Person from whose mouth I took it Sung it thus:

My Chamber was full of wild men’s wine, which is absolute nonsense, but if altered to wild men and Swine, is perfect sense and naturally Expresses a horrid and hurrying Dream."

* * * *

The kiss of death is found in Child 49, Two Brothers in Child B and C (Motherwell c. 1825) his sweetheart (usually Susan/Susie) finds the location of his burial and sings, plays or weeps him from his grave where she asks for a final kiss. The murdered brother warns her that to kiss him would prove to be fatal for her and she sees him no more. In Child 74 after William kisses Margaret's cold clay lips, he dies.

A ballad singer from North Carolina, Betty Smith (see her version titled Little Margaret) has commented that William died from kissing the corpse of Margaret, the revenant kiss:

In "Little Margaret" it says he kissed her lily white hand, her cheek, and then he kissed her clay, cold lips. If you kiss a dead person, you die; and he falls in her arms asleep. It means he died when he actually kissed her. (From Southern Appalachian Storytellers; Page 195- Betty Smith interview).

Of the traditional versions from North America about 10 versions attribute Marg'ret's death to falling out of her window or jumping from her window. In most versions she dies mysteriously; presumably from a broken-heart.

R. Matteson 2013, 2014]

CONTENTS:

1. Child's Narrative

2. Footnotes (Found at the end of the Narrative)

3. Brief (Kittredge)

4. Child's Ballad Texts A-C [One additional version (I'll label D) is given in the Additions and Corrections]

5. Endnotes

6. Additions and Corrections

ATTACHED PAGES (see left hand column):

1. Recordings & Info: Fair Margaret and Sweet William

A. Roud Number 356: Fair Margaret and Sweet William (328 Listings)

2. Sheet Music: Fair Margaret and Sweet William (Bronson's music examples and texts)

3. US & Canadian Versions

4. English and Other Versions (Including Child versions A-C and D with additional notes)]

Child's Narrative

A. a. 'Fair Margaret's Misfortune,' etc., Douce Ballads, I, fol. 72.

b. 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William,' Ritson, A Select Collection of English Songs, 1783, II, 190.

c. 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William,' Percy's Reliques, 1765, III, 121.

d. Percy's Reliques, 1767, III, 119.

B. Percy Papers; communicated by the Dean of Deny, February, 1776.

C. Percy Papers; communicated by Rev. P. Parsons, April 7, 1770.

[D. Communicated by Miss Mary E. Burleigh, of Worcester, Massachusetts, and derived, through a relative, from her great-grandmother, who had heard the ballad sung at gatherings of young people in Webster, Massachusetts, not long after 1820.]

A, a, b, c are broadside or stall copies, a of the end of the seventeenth century, b "modern" in Percy's time, and they differ inconsiderably, except that a has corrupted an important line.[1] Of d, Percy says, Since the first edition some improvements have been inserted, which were communicated by a lady of the first distinction, as she had heard this song repeated in her infancy. Herd, in The Ancient and Modern Scots Songs, 1769, p. 295, follows Percy. As Percy has remarked, the ballad is twice quoted in Beaumont and Fletcher's 'Knight of the Burning Pestle,' 1611. Stanza 5 runs thus in Act 2, Scene 8, Dyce, II, 170:

When it was grown to dark midnight,

And all were fast asleep,

In came Margaret's grimly ghost,

And stood at William's feet.

The first half of stanza 2 is given, in Act 3, Scene 5, Dyce, p. 196, with more propriety than in the broadsides, thus:

You are no love for me, Margaret,

I am no love for you.

The fifth stanza of the ballad, as cited in 'The Knight of the Burning Pestle,' says the editor of the Reliques, has "acquired an importance by giving birth to one of the most beautiful ballads in our own or any language" [that is, 'Margaret's Ghost'], "the elegant production of David Mallet, Esq., who, in the last edition of his poems, 3 vols, 1759, informs us that the plan was suggested by the four verses quoted above, which he supposed to be the beginning of some ballad now lost."[2] The ballad supposed to be lost has been lately recovered, in a copy of the date 1711, with the title 'William and Margaret, an Old Ballad,' and turns out to be substantially the piece which Mallet published as his own in 1724, Mallet's changes being comparatively slight. 'William and Margaret' is simply 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William' rewritten in what used to be called an elegant style. Nine of the seventeen stanzas are taken up with a rhetorical address of Margaret to false William, who then leaves his bed, raving, stretches himself on Margaret's grave, thrice calls her name, thrice weeps full sore, and dies. See The Roxburghe Ballads, in the Ballad Society's reprint, III, 671, with Mr. Chappell's remarks there, and in the Antiquary, January, 1880. The ballad of 1711 seems to have been founded upon some copy of the popular form earlier than any we now possess, or than any known to me, for the last half of stanza 5 runs nearly as it occurs in Beaumont and Fletcher (see also B 7), thus:

In glided Margaret's grimly ghost,

And stood at William's feet.

'Fair Margaret and Sweet William' begins like 'Lord Thomas and Fair Annet,' and from the fifth stanza on is blended with a form of that ballad represented by versions E-H. The brown girl, characteristic of 'Lord Thomas and Fair Annet,' has slipped into A 14, 15, B 8, of 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William.' The catastrophe of 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William' is repeated in 'Lord Lovel,' and it will be convenient to notice under the head of the latter, which immediately follows, some ballads out of English which resemble both, especially in the conclusion.

A c is translated by Bodmer, II, 31, Döring, p. 199; A d by Herder, 1778, I, 124, von Marées, p. 40, Knortz, Lieder u. Romanzen Alt-Englands, No 61.

Footnotes:

1. "The common title of this ballad, which is a favorite of the stalls, is 'Fair Margaret's Misfortunes:' "Motherwell, Minstrelsy, p. lxviii, note 18.

2. Reliques, 1765, III, 121, 310.

Brief Description by George Lyman Kittredge

A, a, b, c, are broadside or stall copies, a of the end of the seventeenth century, b "modern" in Percy's time. The ballad is twice quoted in Beaumont and Fletcher's Knight of the Burning Pestle, 1611 (ii, 8; iii, 5). David Mallet published as his own, in 1724, 'Margaret's Ghost,' which turns out to be simply 'William and Margaret, an Old Ballad,' printed in 1711, with a few changes. The 1711 text is simply 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William,' rewritten in what used to be called an elegant style.

'Fair Margaret and Sweet William' begins like No. 73, and from the fifth stanza on is blended with a form of that ballad. The catastrophe of 'Fair Margaret and Sweet William' is repeated in 'Lord Lovel' (No. 75).

Child's Ballad Texts A-D

'Fair Margaret's Misfortune'- Version A a. Child 74 Fair Margaret and Sweet William

a. 'Fair Margaret's Misfortune' Douce Ballads, I, fol. 72.

b. Ritson, A Select Collection of English Songs, 1783, II, 190.

c. Percy's Reliques, 1765, III, 121.

d. Percy's Reliques, 1767, III, 119.

1 As it fell out on a long summer's day,

Two lovers they sat on a hill;

They sat together that long summer's day,

And could not talk their fill.

2 'I see no harm by you, Margaret,

Nor you see none by me;

Before tomorrow eight a clock

A rich wedding shall you see.'

3 Fair Margaret sat in her bower-window,

A combing of her hair,

And there she spy'd Sweet William and his bride,

As they were riding near.

4 Down she layd her ivory comb,

And up she bound her hair;

She went her way forth of her bower,

But never more did come there.

5 When day was gone, and night was come,

And all men fast asleep,

Then came the spirit of Fair Margaret,

And stood at William's feet.

6 'God give you joy, you two true lovers,

In bride-bed fast asleep;

Loe I am going to my green grass grave,

And am in my winding-sheet.'

7 When day was come, and night was gone,

And all men wak'd from sleep,

Sweet William to his lady said,

My dear, I have cause to weep.

8 'I dreamd a dream, my dear lady;

Such dreams are never good;

I dreamd my bower was full of red swine,

And my bride-bed full of blood.'

9 'Such dreams, such dreams, my honoured lord,

They never do prove good,

To dream thy bower was full of swine,

And [thy] bride-bed full of blood.'

10 He called up his merry men all,

By one, by two, and by three,

Saying, I'll away to Fair Margaret's bower,

By the leave of my lady.

11 And when he came to Fair Margaret's bower,

He knocked at the ring;

So ready was her seven brethren

To let Sweet William in.

12 He turned up the covering-sheet:

'Pray let me see the dead;

Methinks she does look pale and wan,

She has lost her cherry red.

13 'I'll do more for thee, Margaret,

Than any of thy kin;

For I will kiss thy pale wan lips,

Tho a smile I cannot win.'

14 With that bespeak her seven brethren,

Making most pitious moan:

'You may go kiss your jolly brown bride,

And let our sister alone.'

15 'If I do kiss my jolly brown bride,

I do but what is right;

For I made no vow to your sister dear,

By day or yet by night.

16 'Pray tell me then how much you'll deal

Of your white bread and your wine;

So much as is dealt at her funeral today

Tomorrow shall be dealt at mine.'

17 Fair Margaret dy'd today, today,

Sweet William he dy'd the morrow;

Fair Margaret dy'd for pure true love,

Sweet William he dy'd for sorrow.

18 Margaret was buried in the lower chancel,

Sweet William in the higher;

Out of her breast there sprung a rose,

And out of his a brier.

19 They grew as high as the church-top,

Till they could grow no higher,

And then they grew in a true lover's knot,

Which made all people admire.

20 There came the clerk of the parish,

As you this truth shall hear,

And by misfortune cut them down,

Or they had now been there.

-------------

['Sweet William'] Version B; Child 74 Fair Margaret and Sweet William

Communicated to Percy by the Dean of Derry, as written down from memory by his mother, Mrs. Bernard; February, 1776.

1 Sweet William would a wooing ride,

His steed was lovely brown;

A fairer creature than Lady Margaret

Sweet William could find none.

2 Sweet William came to Lady Margaret's bower,

And knocked at the ring,

And who so ready as Lady Margaret

To rise and to let him in.

3 Down then came her father dear,

Clothed all in blue:

'I pray, Sweet William, tell to me

What love's between my daughter and you?'

4 'I know none by her,' he said,

'And she knows none by me;

Before tomorrow at this time

Another bride you shall see.'

5 Lady Margaret at her bower-window,

Combing of her hair,

She saw Sweet William and his brown bride

Unto the church repair.

6 Down she cast her iv'ry comb,

And up she tossd her hair,

She went out from her bowr alive,

But never so more came there.

7 When day was gone, and night was come,

All people were asleep,

In glided Margaret's grimly ghost,

And stood at William's feet.

8 'How d'ye like your bed, Sweet William?

How d'ye like your sheet?

And how d'ye like that brown lady,

That lies in your arms asleep?'

9 'Well I like my bed, Lady Margaret,

And well I like my sheet;

But better I like that fair lady

That stands at my bed's feet.'

10 When night was gone, and day was come,

All people were awake,

The lady waket out of her sleep,

And thus to her lord she spake.

11 'I dreamd a dream, my wedded lord,

That seldom comes to good;

I dreamd that our bowr was lin'd with white swine,

And our brid-chamber of blood.'

12 He called up his merry men all,

By one, by two, by three,

'We will go to Lady Margaret's bower,

With the leave of my wedded lady.'

13 When he came to Lady Margaret's bower,

He knocked at the ring,

And who were so ready as her brethren

To rise and let him in.

14 'Oh is she in the parlor,' he said,

'Or is she in the hall?

Or is she in the long chamber,

Amongst her merry maids all?'

15 'She's not in the parlor,' they said,

'Nor is she in the hall;

But she is in the long chamber,

Laid out against the wall.'

16 'Open the winding sheet,' he cry'd,

'That I may kiss the dead;

That I may kiss her pale and wan

Whose lips used to look so red.'

17 Lady Margaret [died] on the over night,

Sweet William died on the morrow;

Lady Margaret die for pure, pure love,

Sweet William died for sorrow.

18 On Margaret's grave there grew a rose,

On Sweet William's grew a briar;

They grew till they joind in a true lover's knot,

And then they died both together.

-----------

['Fair Margaret'] Version C; Child 74 Fair Margaret and Sweet William

Communicated to Percy by Rev. P. Parsons, of Wye, April 7, 1770.

1 As Margaret stood at her window so clear,

A combing back her hair,

She saw Sweet William and his gay bride

Unto the church draw near.

2 Then down she threw her ivory comb,

She turned back her hair;

There was a fair maid at that window,

She's gone, she'll come no more there.

3 In the night, in the middle of the night,

When all men were asleep,

There walkd a ghost, Fair Margaret's ghost,

And stood at his bed's feet.

4 Sweet William he dremed a dream, and he said,

'I wish it prove for good;

My chamber was full of wild men's wine,

And my bride-bed stood in blood.'

5 Then he calld up his stable-groom,

To saddle his nag with speed:

'This night will I ride to Fair Margaret's bowr,

With the leave of my lady.

6 'Oh is Fair Margaret in the kitchen?

Or is she in the hall?

. . . . .

. . . .

7 'No, she is not in the kitchen,' they cryed,

'Nor is she in the hall;

But she is in the long chamber,

Laid up against the wall.'

8 Go with your right side to Newcastle,

And come with your left side home,

There you will see those two lovers

Lie printed on one stone.

Endnotes:

A. a. Fair Margaret's Misfortune, or, Sweet William's Frightful Dreams on his Wedding Night. With the Sudden Death and Burial of those Noble Lovers. ... Printed for S. Bates, at the Sun and Bible, in Giltspur Street. Sarah Bates published about 1685. Chappell.

31. set.

41. lay.

54. Which causd him for to weep: caught probably from 74. See the quotation in Beaumont and Fletcher, and the other broadside copies.

132. my kin.

181. channel.

b. 11. out upon a day.

13. a long.

24. you shall.

34. a riding.

43. went away first from the.

44. more came.

54. And stood at William's bed-feet.

61. you true.

63. grass green.

64. I am.

94. thy bride-bed.

101. called his.

121. Then he.

123. she looks both.

141. the seven.

143, 151. brown dame.

162. Of white.

182. And William.

193. there they.

194. all the.

201. Then.

c. 23. at eight.

24. you shall.

33. She spyed.

34. a riding.

44. more came.

53. There came.

54. And stood at William's feet.

61. you lovers true.

64. I'm.

94. And they.

121. Then he.

141. the seven.

17. William dyed.

182. And William.

193. there they.

194. Made all the folke.

201. Then.

d. Variations not found in c: "Communicated by a lady of the first distinction, as she had heard this song repeated in her infancy."

32. Combing her yellow hair.

33. There she spyed.

4. Then down she layd her ivory combe,

And braided her hair in twain;

She went alive out of her bower,

But neer came alive in 't again.

6. 'Are you awake, Sweet William?' shee said,

'Or, Sweet William, are you asleep?

God give you joy of your gay bride-bed,

And me of my winding-sheet.'

113. And who so ready as her.

153. I neer made a vow to yonder poor corpse.

16. 'Deal on, deal on, my merry men all,

Deal on your cake and your wine;

For whatever is dealt at her funeral today

Shall be dealt tomorrow at mine.'

191. They grew till they grew unto the.

192. And then they.

193. they tyed.

194. the people.

C. "The ballad of Sweet William," writes Parsons to Percy, "was the same as yours in the stanzas I have omitted. ... The person from whom I took the thirty-fifth line [thirty-first, here 43] sang it thus:

My chamber was full of wild men's wine,

which is absolute nonsense, yet, if altered to 'wild men and swine,' is perfect sense."

P. 199. The Roxburghe copy, III, 338, Ebsworth, VI, 640, is a late one, of Aldermary Church- Yard.

200 b. A c is translated by Pröhle, G. A. Bürger, Sein Leben u. seine Dichtungen, p. 109.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

P. 199. [Designated D] Communicated by Miss Mary E. Burleigh, of Worcester, Massachusetts, and derived, through a relative, from her great-grandmother, who had heard the ballad sung at gatherings of young people in Webster, Massachusetts, not long after 1820.

1 There was such a man as King William, there was,

And he courted a lady fair,

He courted such a lady as Lady Margaret,

For a whole long twelve-month year.

2 Said he, 'I'm not the man for you,

Nor you the maid for me,

But before many, many long months

My wedding you shall see.'

3 Said she, 'If I'm not the maid for you,

Nor you the man for me,

Before many, many long days

My funeral you shall see.'

4 Lady Margaret sat in a green shady bower,

A combing her yellow, yellow hair,

When who should she see but King William and his bride,

And to church they did repair.

5 She threw all down her ivory comb,

Threw back her yellow hair,

And to the long chamber she did go,

And for dying she did prepare.

6 King William had a dream that night,

Such dreams as scarce prove true:

He dreamed that Lady Margaret was dead,

And her ghost appeared to view.

7 'How do you like your bed?' said she,

'And how do you like your sheets?

And how do you like the fair lady

That's in your arms and sleeps?'

8 'Well do I like my bed,' said he,

'And well do I like my sheets,

But better do I like the fair lady

That's in my arms and sleeps.'

9 King William rose early the next morn,

Before the break of day,

Saying, ' Lady Margaret I will go see,

Without any more delay.'

10 He rode till he came to Lady Margaret's hall,

And rapped long and loud on the ring,

But there was no one there but Lady Margaret's brother

To let King William in.

11 'Where, O where is Lady Margaret?

Pray tell me how does she do.'

'Lady Margaret is dead in the long chamber,

She died for the love of you.'

12 'Fold back, fold back that winding sheet,

That I may look on the dead,

That I may kiss those clay-cold lips

That once were the cherry-red.'

13 Lady Margaret died in the middle of the night,

King William died on the morrow,

Lady Margaret died of pure true love,

King William died of sorrow.

14 Lady Margaret was buried in King William's church-yard,

All by his own desire,

And out of her grave grew a double red rose

And out of hisn a briar.

15 They grew so high, they grew so tall,

That they could grow no higher;

They tied themselves in a true-lover's knot,

And both fell down together.

16 Now all ye young that pass this way,

And see these two lovers asleep,

'T is enough to break the hardest heart,

And bring them here to weep.

199 f. Mallet and 'Sweet William.' Full particulars in W. L. Phelps, The Beginnings of the English Romantic Movement, 1893, p. 177 ff.