FRANK NOAH PROFFITT: Good Times and Hard Times on the Beaver Dam Road

by ANNE WARNER and FRANK WARNER

Appalachian Journal, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Autumn 1973), pp. 163-193

[Great article on Frank Proffitt. My grandfather, Maurice Matteson, is mentioned in the first part, 6th paragraph following the first photo: "In the spring of that year we met a professor from South Carolina, Maurice Matteson, who had just come to New York from a song-collecting trip in the southern mountains with a dulcimer made, he told us, by Nathan Hicks of Beech Mountain, whose address was Rominger, North Carolina." It's interesting that this introduction ultimately led to Tom Dooley being recorded by Kingston Trio, securing Proffitt's place in traditional music. R. Matteson 2011]

FRANK NOAH PROFFITT: Good Times and Hard Times on the Beaver Dam Road

By ANNE AND FRANK WARNER

[Frank and Anne Warner have collected songs, and friends, in many out-of-the-way places in America. Aside from close associations with the Newport Folk Foundation and many other organizations that promote folk art and folk history, Frank Warner is himself a renowned performer in the folk tradition. held philosophy that made Frank Proffitt a winning spokesman for his mountain people.]

[Listen: Beaver Dam Road by Frank Proffitt]

To all of those who's mind reaches above the hard facts of Life does a Ballad have its meanings. With thease songs did our Forebears cheer their weary hearts in the New Ground Clearings. Life to them was not dull for in their amagination they had a world of their own. This world they built is not for thouse who see only the dull drab facts of their surrond- ings, but only for folk of kindred minds seeking to preserve and exault a people of undaunted spirit who excepted [ac- cepted] Life in a singing spirit, reaching in their hearts for things to brighten the days and years. I may neaver see the Lochs or Braes of my people. But in my amagination I have this world of old castles, of high Lord Chieftans, of those who used the sword . . . To thouse who sleep in the soil far from the Bonnie Braes, my hope is they have not lived for nothing.

[Frank Proffitt with Bessie's great aunt Buna (Mrs. Roby Hicks) playing for Bessie's brother Ray Hicks' dancing. Mrs. Nathan Hicks and neighbor children in the rear, on her porch on Beech Mountain. 1959.]

[My father, Richard Matteson Sr., made two trips to Beech Mountain with my grandfather. My father was just 4/12 years old the first trip and 6 1/2 years old the second. He remembers playing and wrestling with Ray Hicks (see photo above) and members of the Hicks family. He was also in NY during the time Frank Warner met my grandfather.]

Frank Proffitt wrote these lines (above photo) on the first page of a notebook full of remembered songs he gave to us in 1964 - the fourth such book since 1940. The words express a deeply-held philosophy that made Frank Proffitt a winning spokesman for his mountain people. When Frank Proffitt died in November of 1965, the New York Times carried a six-inch double-column story, and stories about him appeared in leading papers across the country, among them the New York Herald Tribune, the Long Island Press, the Greensboro Record, the Miami Herald, the Chicago Tribune.

The Watauga Democrat, in Boone, North Carolina, in addition to its news story, carried an editorial that said, in part, "It is with anguish that we chronicle the death of Frank Proffitt who had such strong affection for these mountains, and who, in his writings, was beginning to share with followers of traditional music his admirable convictions about life."

Frank Proffitt lived all his life in rural Watauga County, North Carolina. He had a sixth-grade education. He did hard scrabble farming on his steep and rocky land high in the mountains. Yet during the last five years of his life he had a profound effect on folk music in this country and beyond our shores and on uncounted individuals. How this came to be is an important story, particularly to us, for Frank's influence on our lives can never be fully told.

Frank was born on June 1, 1913, in Laurel Bloomery, Tennessee, the son of Wiley and Rebecca Alice Creed Proffitt. His grandparents were John and Adeline Perdue Proffitt, who moved to the Cracker Neck section of the eastern Tennessee mountains from Wilkes County, North Carolina, shortly after the Civil War. Frank's grandfather, John Proffitt, went across the state line to join the boys in blue (as Frank sings in "Going Across the Mountains"), and was a member of the 13th Tennessee Cavalry, U.S.A. When Frank was a young boy the family moved back to North Carolina to the Beaver Dam Section of Watauga County just a few miles below the Tennessee border.

There his father made a living as a farmer and cooper and tinker, "fixing anything that was brought in," Frank once told us, "watches, clocks, guns, churns, anything he could fix ... along with it he made a banjer now and then." Frank said that in his boyhood his life was like that of the pioneers "that had existed from the earliest mountain settlers. . . . These were the folk who asked nothing of other men and didn't bother you with trifles." Wiley, Frank's father, was middle aged "before he ever saw a good-sized town," Frank said, "yet he lived as interesting a life as one could ask for." Frank was sixteen when he walked barefoot across the mountains to see his first town - Mountain City, Tennessee.

Frank moved in his relatively short life from a colonial pattern to the sophistication of the mid-twentieth century, to talking and singing to college audiences, to making commercial recordings, and to corresponding with people around the world.

In 1938 we were recently married and were living in Greenwich Village in New York City - though Frank Warner had been raised in North Carolina, in Durham. In the spring of that year we met a professor from South Carolina, Maurice Matteson, who had just come to New York from a song-collecting trip in the southern mountains with a dulcimer made, he told us, by Nathan Hicks of Beech Mountain, whose address was Rominger, North Carolina. We very much wanted a dulcimer ourselves, so we wrote to Nathan Hicks to see if he would make one for us, which he was happy to do.

This began our correspondence with the Hicks family. Nathan and his wife Rena wrote us about their ten living children and the ones they had lost. Their three oldest were married and the baby, Jack, was just two months old. They were proud people, but they wrote of their struggles and their great need. "When it's blue cool hear, the stove heats the house just enough to live." That spring their cabbages all froze so they couldn't sell any. Though they would have sold for only fifty cents a hundred pounds, that "would have been better than nothen." We began to badger our friends to give us clothes and bedding to send down. And we decided to go to visit the family as soon as we could.

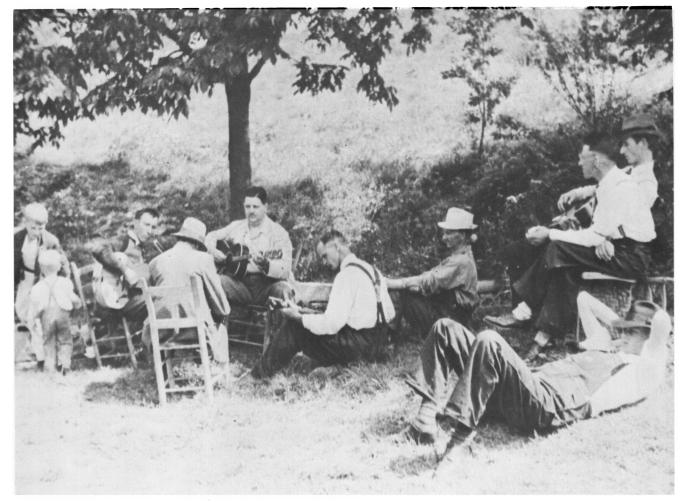

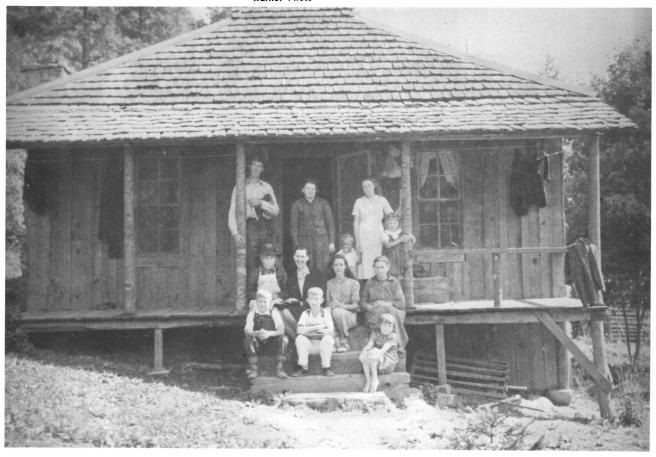

It was June 5, 1938, when we first reached the house on Beech Mountain. A crowd of some twenty-five kin-folk and neighbors were waiting for us - with guitars, homemade banjos, dulcimers, fiddles, and French harps. The best singer and guitar player among them turned out to be Nathan's son-in-law, Frank Proffitt, who had walked ten miles across the mountains from his home in Pick Britches Valley to sing with us.

[Warner Photo. Song swapping session on the Warner's first visit to Beech Mountain. Frank Proffitt at left, Frank Warner facing camera. 1938.]

In 1946 the name Pick Britches (in pioneer times there were many briars thereabout) was changed, officially, to Mountain Dale, in the American tradition of prettifying pioneer names. We hope the residents of Mountain Dale will forgive us, but we prefer the old name, as did Frank Proffitt. And in 1938 Pick Britches was, indeed, its name. With Frank that day was his wife Bessie and their son, Oliver, then five years old. Bessie was Nathan and Rena's oldest daughter. There too that day were the children - Lewis and his wife Mary and their baby, Roger; Mae and her husband Linzy, Ray, N. A., Anna, Willis, Nell, Betty, and Little Jack. Roby Monroe Hicks, Nathan's uncle, was there. Nathan's father Ben Hicks came during the afternoon, and with him a trio of little girls who sang a song for us with their eyes tightly shut.

Before long everybody was making music. The sound, and the people, that afternoon gave us a feeling we have never lost. It was the beginning of our life-long interest in traditional music and the people who remember it. We had not come with the idea of collecting songs, but Anne couldn't help taking down in shorthand the words of three songs Frank Proffitt sang: "Dan Doo," a version of the Child ballad, "The Wife Wrapt in Wetherskin;" "Moonshine," a story about the effect of homemade liquor; and "Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley," the song that twenty years later would have such an impact on Frank Proffitt, on us, and on the world.[1]

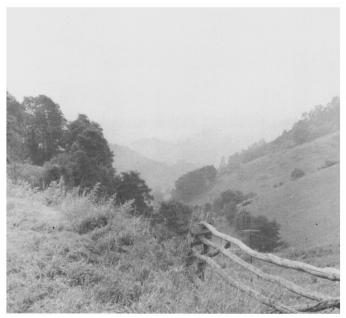

Warner Photo: George's Gap, Watauga County North Carolina

After our first visit to "the Beech" (as everyone refers to Beech Mountain) we knew we would be going back whenever we could. At Christmas time we sent a box of clothes and toys and goodies for all the children, and to our joy we received a box of greens freshly picked on the mountainside - galax leaves and wintergreen and running cedar. Last Christmas, in 1972, we welcomed such a box for the thirty-fifth time.

[My grandfather, Maurice Matteson and grandmother always sent food and clothes and received in exchange a box of Galax leaves. One Christmas my grandmother received the Galax leaves and then realized she'd forgotten to sent them the annual box of food and clothes- she gathered up the items and sent them the next day. Interview with Richard Matteson Sr.]

In 1939 we had more of a chance to talk to Frank and to explain why we had become interested in saving the old songs. This struck a responsive chord, and he wanted to know all we could tell him about what the songs meant and their historical significance.[2]

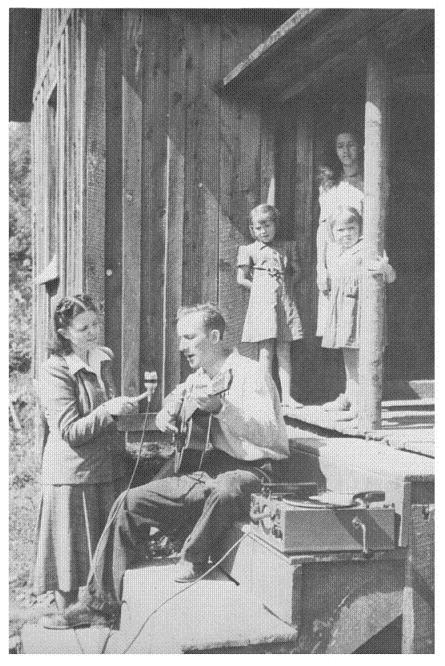

By the time of our visit in 1940 we had a recording machine, a Wilcox Gay Recordio. This was pre-tape days and the machine cut grooves in small disks. There was no electricity on the Beech or in Pick Britches. That would have to wait for the TVA dam to be built. So we took as many of the family as we could get in the station wagon and went down the mountain to Matney, to the home of friends named Rominger, who did have electricity. Once we went to a filling station onthe highway. None of this was very satisfactory, but we did record many fine songs.

The first letter from Frank Proffitt we have saved is dated November 9, 1940. In it he says, "It was with the greatest of pleasure that I received a few days ago a letter from you and the pictures enclosed. The songs which I was telling you about I am getting from my father and my aunt ... I am going to send to you sometime soon."

This he did - a copybook filled with songs he had written out for us. Let us say a word about Frank's letters to us. Many have disappeared over the years, but we still have some two hundred and twenty-three of them. From 1959 through 1965 they came at the rate of about two every month - sometimes oftener. After sixth grade at a mountain schoolhouse Frank quit school to work full time on his father's farm, but his education never stopped. Throughout his life, he told us, he read whatever books and papers he could lay his hands on. He spent much time thinking and pondering, on rainy days or during long winter evenings. He spoke, and wrote, in the style of early nineteenth-century America or, often, in an earlier pattern. He kept many of the idioms of the first comers, who came to these shores not long after the era of the King James translation of the Bible, with its beautiful cadences. Sometimes Frank's phrases sounded biblical. Sometimes Bible verses come to mind in thinking of him. His letters are unusually revealing.

I may neaver see the Lochs or Braes of my people. But in my imagination I have this world of old castles, of high Lord Chieftans, of those who used the sword ... To those who sleep in the soil far from the Bonnie Braes, my hope is they have not lived for nothing. [Quote from Frank Proffitt]

As Frank Warner wrote in 1963 in an article on Frank Proffitt for Sing Out! magazine, "His intelligent grasp of ideas, his amused and compassionate understanding of people, his fun and humor, the iron of his own integrity, are a source of constant satisfaction to his friends. His letters are like his talk - poetic in feeling, full of fun, restrained, but articulate and precise. They don't leave you in any doubt."

In quoting from Frank's letters we hope we will be forgiven for including expressions of gratitude and apprecia- tion for our friendship. Our letters to him, too, were full of expressions of this kind, because we had an equal effect on each other's lives. Re-reading Frank's letters, we have a fresh realization of the quality and depth of our friendship. We wrote him about whatever we were doing or thinking, knowing that his reactions and response would be warm and satisfying.

Once he wrote us, "When something interesting happens nowadays I think of you first to tell it to. I think this is a great way to do, and I know I love to hear about all the things that happen to you." And again, "If I could make you understand how all the things our knowing each other means, it would be so great."

By 1941 our friend David Grimes, who was vice president of Philco, had become interested in our project, since Frank Warner had done some experimental television shows for Philco in Philadelphia. That year David Grimes created for us in the Philco laboratory a battery-powered portable recording machine. In the summer we spent several days with the Hickses on the Beech and then went over to Pick Britches to stay with Frank and Bessie and Oliver in the two-room cabin Frank had built with his own hands when he and Bessie were married.

[Anne Warner recording Frank Proffitt's singing and playing on a small battery-powered recording machine in 1941, while some neighbor children listen. In the Beaver Dam section of Watauga County, N. C, known then as Pick Britches Valley, and now as Mountain Dale, Warner Photo]

In the mountains then people got up before dawn, and so they went to bed early, but during our visit Frank sat up with us each night until midnight, talking about his boyhood and his people and asking us questions about New York and "the beyont" in general.

"The other world," he used to call it years later after he'd been out in it himself. We had made up a list of words that occur frequently in folksongs and ballads, as a tool to help informants remember songs. Frank was intrigued. As Anne would go down the list - dagger, lady fair, the castle gate, salt sea, etc., he would stop her with "Yes, I know a song with that in it. It's called. ..."

Anne would list the titles and the next day, on our new little wind-up Philco, we would record the tunes of the songs, while Anne wrote down all the words. In July of 1941, after our visit, Frank wrote us, "Yes, I will get you the words to The Faded Coat of Blue,' and some others, The Drummer Boy,' for one . . . and I will try to learn the tunes also. My aunt is feeling some better now."

Frank's Aunt Nancy Prather gave him many of his songs. "I am going to do all I can to help get the songs for I too want them formy collection. I want my folder to grow big and fat."[3]

In a letter dated September 23, 1941, after expressing pleasure at hearing from us, Frank wrote:

It is is beginning to get cool here now. It won't be long I know until frost nips the green growing things and turns them brown. Its been very dry here and the stream flowing by my house is getting so low that it dont turn the water wheel so fast any more but fast enough to keep my radio battery charged (I have a radio) to keep playing. By the way I've been a squirrel hunting twice this fall. They are cutting hickory nuts now up on the Horse Ridge. I seen six in one tree. The nuts was sure hitting the ground. Browned squirrel and squirrel gravy and biscuits, coffee, and a little more gravy is not so bad thease chilly mornings. . . . I wish you was here. We'd show the wimmin how to eat. I haven't been outto Nathan's since you all were here but Bessie has been there canning plums. . . . She stayed a week. I didn't like to be left that way but didnt see much I could do about it. . . . My beans done fairly well. We sold six thousand lbs. My back got mighty tired before we got done. They brought us from 3V2 0 to 50 per Ib. I sold my calves the other day. They was 3 months old and brought me $50 for the two. . . . I hope you can come again and we'll have a good old time and sang and sang, on and on, til we get tired. . . ."

From a letter dated January 1, 1942:

We was very much pleased to get the nice Christmas box . . . Oliver was over- joyed to get his big new flashlight, he goes to grandpas ever night just to get to use it lighting his way. . . . Bessie has been sick and myself to, and doctor made it pretty hard on us and we didnt have very much to spend for Christmas and the things you sent us helped a great deal. We both are well now and I am planning on going across in Tenn. . . . about 30 miles to where the government is starting a big Dam, which cost about 24 millions dollars, and working. They are going to use about two thou- sand men. T.V.A. Project. I guess you both are very busy, more so since the war. . . . Again thanking you both . . . and hoping we can keep singing our good old American songs (and not Hitt- lers) for many years to come. . . ."

The only correspondence saved from 1943 is two postcards, one dated January 28 announcing the birth on January 18 of the Proffitts' second son, Ronald Ray, and one dated March 24 congratulating us on the arrival of our son, Jonathan Francis, on March 9.

Only a few of our letters from the Proffitts between 1943 and 1959 have survived, although we know we communicated every Christmas and in between. We know three more Proffitt children were born before 1951: Franklin B. (now known as Frank, Jr. ), Phyllis, and Eddie.[4] We have the announcement of Oliver's graduation from Bethel High School in 1950, and a note from him thanking us for the gift we sent.

We know that during these years Frank worked for a time at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as a carpenter, without any knowledge of what work was being done there. Later he worked in Toledo, Ohio, in a spark-plug factory. In Toledo, he told us, he stayed with some other mountain people who had gone there to work, and he saw little of the city or its ways. Many times, when money ran out, he left home to take temporary jobs at carpentry or road building.

Earlier in his life, during the depression, before we knew him, he had worked for the Works Progress Administration, doing whatever job was offered. He sang us a song put together by the local boys during that period, about which he wrote, "Of all the things that have ever happened in the mountains nothing has ever equalled the coming of the work program that Franklin D. Roose- velt put in effect that was known as the W.P.A. Out of the hollers, out of the ridges, the roads was filled with signers who wanted to get on the 30£ per hour, $9 per week bonanza. Of course everyone couldn't get on, out of it was much bitterness and hatred. But those who 'got on' had a wonderful feeling of eating high on the hog." Here are a few verses of the song:

Where did you get that pretty dress

All so bright and gay? I got it from my loving man

On W. P. and A.

Chorus: On W. P. and A.

On W. P. and A.

I got it from my loving man

On W. P. and A.

I said hello to my best friend

But nothing would he say

I seen right then he'd tried to get

On W. P. and A.

I axed for credit at the store

The man he said OK

He know'd darn well I had a job

On W. P. and A.

Farewell to hoeing in the corn

Goodbye cutting hay

I'd rather go and make my dough

On W. P. and A.

During the Second World War gasoline was rationed and obtainable only for essential driving, so, eventually, we sold our car and trips to the mountains during those years became impossible.

By 1951 the war was well over and we, at last, had put together enough money for a new car. The Warners, now four, headed back to the Blue Ridges. Nathan Hicks, alas, had died, but we stayed with Rena and saw many other members of the family, including Ray and his wife Rosa and their two children. Jack, now thirteen, introduced our little boys to the mountains, taking them up on a high ridgeto milk the cow and, with a bucket of milk in each hand, running down a slope they could scarcely navigate. He let them play with his pet rabbits and his groundhog. Ray let them ride his big white work horse. We all walked up on the South Pinnacle again to glory in the sight of the valley dropping down from the Beech and of Grandfather Mountain and the other peaks rising on and on to the horizon. Standing there in the northwest corner of North Carolina, we knew we were seeing the mountains of Tennessee on one hand and of Virginia on the other.

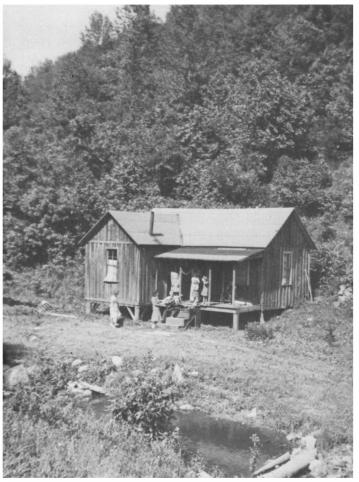

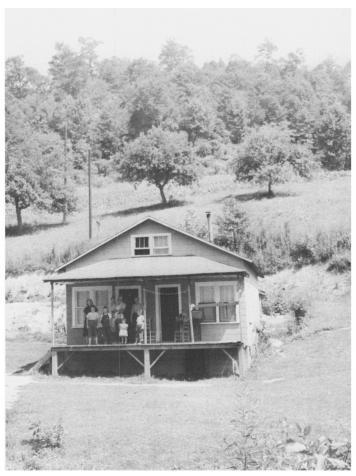

[Frank Proffitt with family and kin at his father's old home in the Beaver Dam section of Watauga County. 1941. Warner Photo]

By this time we had a tape machine. Tape opened a new world. With tape it didn't matter if a singer could not remember a word or a line or a verse, since the tape would wait until he did remember it. Even more importantly, tape made it possible to record discussions and conversations and reminiscences. During this visit we re- corded several hours of Roby Hicks (then sixty-nine years old) remembering his early days in the mountains and those of his forebears, the first settlers there, who brought in with them only an axe, a gun, salt, and "sody."

We had written the Proffitts that we would be coming, but when we got over to Pick Britches where they were living in the larger second house Frank had built for the family on land inherited from his father, we found only Bessie and the children - all the children, that is, except Oliver, who by now had joined the Air Force.

Frank was away. He had taken a job working on the road somewhere and, Bessie said, he had sold his guitar and wasn't singing any more. That was sad news. We knew it was the terrible struggle to make a living that had forced him to give up his music, and we knew too that giving up his music was a proof of his despair. Years before, when Nathan had lost all his pay crop of cabbages in a spring freshet, he took his dulcimer under his arm and walked over to Frank's "to play the misery out of his soul." Without that solace a mountain man was poor indeed. We have a letter from Frank dated December 30, 1951.

"We received the nice box of presents and what a time the kids are having. . . . Oliver was home for the holidays and he's put on several pounds. He's training for Air Police and he is big enough to handle his job looks like. . . . We hope you can come down next summer and we will arrange to have you spend a few days with us. The boys can climb some of the hills and see what's on the other side. . . ."

Still no mention of music. Some time after this, in 1955, a sixth and last Proffitt child was born- Gerald. We know he was welcome, but there were now many mouths to feed and living was hard. As the song says:

I've worked like a dog and what have I got?

No corn in the crib, no beans in the pot.

Oh, it's hard times on the Beaver Dam Road,

It's hard times, poor boy.[5]

[Listen: Beaver Dam Road by Frank Proffitt]

"Tom Dooley" was one of the first songs Frank Proffitt gave us. It was the first song he remembered hearing his father pick on a banjo. Frank's grandmother, Adeline Perdue, lived in Wilkes County and knew both Tom and Laura, for Tom Dooley - really Tom Dula - did live. Dula was called Dooley in the mountains, as Rosa is called Rosy, or Buna is called Buny. Tom was a native of Wilkes County and was known to be a wild one. He rode hard and drank hard and had a way with the ladies, especially Laura Foster. When the Civil War came he joined the Confederates and fought until he was taken prisoner and put in a stockade at Kinston, North Carolina. After the war he made his way home on foot, and took up his old ways. He renewed his relationship with Laura, but also was involved with Ann Melton, though she had a husband and two children. One day, at Ann's instigation, many believed, Tom lured Laura Foster into riding off with him. On the hillside - again, it is said, with Ann's help - he stabbed Laura and buried her in a shallow grave. It is a sordid tale, well covered even by the New York papers who sent correspondents to cover the two trials, which lasted two years. Tom, to the end, refused to implicate Ann, though she had been arrested too, so eventually she was freed, and Tom was convicted and hanged in 1868.[6]

[Listen: Tom Dooley by Frank Proffitt]

[music- Tom Dooley]

[The Warners collected Tom Dooley from Frank Proffitt in 1938. Frank Warner recorded Proffitt's version for Elektra in 1952. Warner passed it to Alan Lomax who published it in Folk Song: USA. Proffitt's version eventually was recorded The Kingston Trio, on Capitol, in 1958. This recording sold in excess of six million copies, topping the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart, and is often credited with starting the "folk boom" of the late 1950s and 1960s. It only had three verses (and the chorus four times). This recording of the song has been inducted into the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress and been honored with a Grammy Hall of Fame Award.

Proffitt regarded the song as his song, as he learned it from his father. The song was in oral tradition in the region since 1866 when the murder happened and was recorded by Grayson and Whitter as "Tom Dula" in 1929.]

Many songs were written about Tom Dooley, but it is the one that came down in Frank's family that eventually went around the world. We have a copy of a letter Frank Proffitt wrote in 1959 and sent to Billy Faier who was planning a book on folksongs and wanted to include something about Tom Dooley. The book didn't come out, but this is what Frank wrote:

My early est recalection is of waking on a cold winter morning in a log cabin on old Beaver Dam and hearing the sad haunting tune of Tom Dooly picked by my father (Wiley) along with the frying of meat on the little stepstove and the noise of the little coffeemill grinding the Ar buckle [coffee]. What better world could they be for a small boy who was hungry for the fried meat and biscuit, and hungry aliso to make sounds like grown up on a curley walnut banjer.

In thouse days after the crop was laid by folks went a-visiting. Dad would hang the banjer around his neck, [take] a rifle and lantern and we would go to see the folks. As they gathered around the fireplace with a pine knot burning, us younguns would get a place down on the floor and listen to Tom Dooly and other songs being played. Then they would stop and tell us how Tom rode a-courting, a-picking [his banjo] up and down the roads . . . and even picked once in the churchyard whilst the preacher was a-preaching. . . .

I started soon to trying to pick the ban- jer. Soon the happy day came when Dad said, "I declare you air just about got Tom Dooly a-going." . . . Soon when the men came to get watches fixed I went to singing Tom for them . . . and other songs. Along the road to school to the mill with my brother as at the store, they had me a-singing. They would say, that boy know all of that Tom Dooly. . . . I married into another singing family of Nathan Hicks and with his dulcimer I went on with the kind of life I loved. . . .

Then Frank Warner come to the mountains and in him I saw a addgicated person who made me feel like somebody, and I open my heart to him and gave him the old songs of my people. His eyes sparkled as I sing Tom Dooly to him and told him of my Grandmaw Proffitt knowing Tom and Laura. . . . I told him of my people and he and Anne didn't seem to notice that we was pore and didnt know big words. They bragged on our new calf, our little two room cabin, and brought store stuff for us all to eat. I walked on air for days after they left. . . . Time rolled on and I just quit trying to sing although my heart would about bust once in awhile.

[What better world could they be for a small boy who was hungry for the fried meat and biscuit, and hungry aliso to make sounds like grown up on a curley walnut banjer.]

. . . I got a television set for the kids. One night I was a-setting looking at some foolishness when three fellers stepped out with guitar and banjer and went to singing Tom Dooly and they clowned and hipswinged. . . . I began to feel sorty sick, like I'd lost a loved one. Tears came to my eyes, yes, I went out and balled on the Ridge, looking toward old Wilkes, land of Tom Dooly. . . .

[I looked up across the mountains and said Lord, couldn't they leave me the good memories.]

. . . Then Frank Warner wrote, he tells me that some way our song got picked up. The shock was over. I went back to my work. I begin to see the world was bigger than our mountains of Wilkes and Watauga. Folks was brothers, they all liked the plain ways. I begin to pity them that hadn't dozed on the hearth- stone. . . . Life was sharing the different thinking, the different ways. I looked in I looked up across the mountains and said Lord, couldn't they leave me the good memories. . . . the mirror of my heart - You haint a boy no longer. Give folks like Frank Warner all you got. Quit thinking of Ridge to Ridge, think of ocean to ocean.

After Frank taught us his favorite mountain song it became one of our favorites. From 1939 to 1959 Frank Warner used Tom Dooley in every lecture and program, telling the story of Tom and of Frank Proffitt, and singing his own modification of Frank's song. He had eliminated two verses that weren't relevant, put the rest in what seemed chronological sequence, and, over many years, had unconsciously reshaped the melody line to fit his own feeling about the song. Frank Warner taught his version to Alan Lomax, who included it - minus the second stanza - in Folk Song USA in 1947, with due credit.

It was this version Frank Warner included in his Elecktra album (EKL 3) in 1950, with Frank Proffitt's story in Anne's jacket notes. It was the Folk Song USA three-stanza version which the Kingston Trio recorded for Capitol Records in 1958, both on an album and as a single which sold over three million copies. The song made the top of the hit parade, and is generally credited with initiating a world-wide wave of enthusiasm for American folk music. We were sent recordings of "Tom Dooley" from London and Germany, sheet music from Italy, Spain, Australia, even Japan. Traveling friends have sent us stories about hear- ing "Tom Dooley" sung in many countries - in Scotland by two little boys sitting in a tree, for instance, and in India by school children who had adapted it to fit a local situation - "Hang down your head, Matavani."

Everyone began to take a new look at existing copyright laws and practices. Most people who sang folk songs at that time had never throught of copyrighting a song. Now "writer's" royalties were being collected by young singers here and abroad on songs widely known and widely sung before they were born. It seemed only fair that rights be shared by collectors who had spent time and effort and their own money on field collecting. More importantly, an informant should share these rights. The only existing copyright on "Tom Dooley" was the one covered by Folk Song USA. The Richmond Organization, which came eventually to hold our interest and Frank Proffitt's and Alan Lomax's, conferred at length with Capitol Records, and eventually there was an out-of-court compromise which gave TRO full rights to the song as of January 1, 1962 - well after the time of its greatest popularity. Since that time any royalties coming in have been divided equally between the three people involved.

Frank's share, since his death, has gone to Bessie, his wife. Royalties from "Tom Dooley" - though not approaching the pre-1962 scale - did make a substantial difference in Frank's life. Amazingly, some royalties have continued to trickle in through the years. Beyond the actual money, however, Tom Dooley completely changed Frank's life and his standard of living. We have a letter from Frank dated January 14, 1959.

"There was a few things I wanted to say that I might not have time or think of when we meet. . . . There was the usual gang around the store when you called me so I didnt talk much . . . but I did understand that they was some possibility of money for us. I wouldnt bore you with telling what getting something will mean to us, for frankly we are in pretty desperate condition. Anything that helps will seem like a divine gift."

Frank Jr. told us not long ago when he was at our house for a visit in connection with a short concert tour, that he remembered "just before the folk music started" that often the family had nothing to eat but potatoes three times a day, and not enough of that. Word got around that Frank Proffitt was the source of the song "Tom Dooley." In 1960 J. C. Brown, then editor of the Carolina Farmer (now Carolina Country), a magazine which reaches nearly all the rural folk of North Carolina, wrote a warm enthusiastic story about Frank in two issues of the publication. This gave Frank a new status with his neighbors. Suddenly there were many newspaper interviews, letters from across the country, visits from strangers, and orders for the homemade fretless banjos Frank had begun to make to his father's pattern. Eventually there was such a demand for these and for the dulcimers he also made that he could scarcely keep up with orders. We sold perhaps thirty for him in New York City. Pete Seeger ordered a banjo, and Billy Faier and Bill Bonyun and Bonnie Dobson and Sandy Paton, and dozens through the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago. Orders came from around the world. But all this was later.

[Frank and Bessie Proffitt's first home in Pick Britches Valley. 1941. Warner Photo]

Frank wrote of the banjo making:

As a boy I recall going along with Dad to the woods to get the timber for banjer-making. He selected a tree by its appearance and by sounding - hitting a tree with a hammer or axe broad- sided, to tell by the sound if its straight grained, sound, shaky, faulty, or hollow. I do this myself also. . . . I cant describe it in words but I see inside the tree by the sound of hitting it. . . . My father would cut the tree down and saw it up in neck lengths. Then set the blocks on their ends and lay off in squares. This is my way also, using a maul and wedges to split the squares for banjer necks. I then as Dad taught mey stick the squares in ricks to air dry for six months or more . . . after . . . they are taken and put over a stove or fireplace to kiln dry ....

On March 9, 1959, before the TRO- Capitol settlement, Frank wrote,

"The Tom Dooley case sounds a little bad, but don't feel badly on my part if we dont win, for I have got more out of it than you realize. ... I got to meet you again . . . and to know that what we love millions of others do also. . . ."

In 1960, at Alan Lomax's request, Frank made a gourd banjo like those used in the days of slavery, for a film that was being made at Williamsburg, Virginia. He knew how to do it. He told us he remembered as a boy making banjos out of the "gords Mama grew," and stringing them with stove pipe wire. He said they had a "gosh awful sound!"

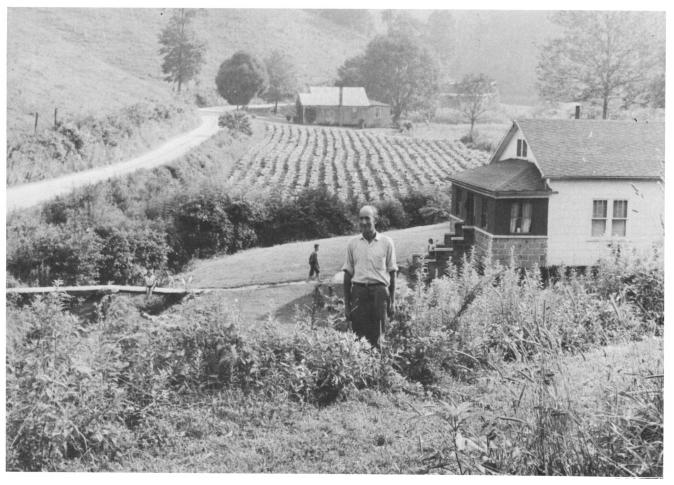

[Frank Proffitt at his house, with tobacco patch in the rear. 1959. Warner Photo]

1961 was a great year. In February the University of Chicago held its first annual Folk Festival, the first big festival devoted largely to traditional singers. Participating, in addition to Frank Proffitt, were Horton Barker, Roscoe Holcomb, Elizabeth Cotton, Memphis Slim, Willie Dixon, and among others, the Stanley Brothers, the New Lost City Ramblers, Alan Mills and Jean Carignan from Canada, Richard Chase, and Frank Warner. Frank Proffitt had been reluctant to go. "I'm a shy mountain man," he said. But he had been persuaded. The two Franks and Horton Barker stayed with George and Gerry Armstrong with whom Frank Proffitt had become acquainted when Dick Chase brought them to see him in the mountains. George became a real friend and did a great deal for Frank in the years to come.

On the night of their appearance Frank Warner and Frank Proffitt stepped out on the stage together. Frank Warner had asked for all the spotlights so that Frank Proffitt would not be able to see the thousands of people in the big auditorium, since he had never been on a stage before. Frank Warner sang a song he had learned from Frank Proffitt and asked Frank to sing something for him. The response was immediate and immense. The audience took Frank to their hearts. He could have no further doubt of his acceptance as a true mountain singer.

Quoting again from Frank Warner's Sing Out! article, "Those who had known the feel of real mountain music, who had wakened in the moun- tains at sunup hearing a banjo picker starting the day right and had felt that pricking of the scalp that true poetry, or any true art, gives - we, who had long known Frank's way with a tune - were not surprised." Writing of the festival in the May 1961 issue of WFMT's Chicago Fine Arts Guide, Studs Terkel (well known Chicago commentator who was the festival's master of ceremonies) said that it was the real folk singers - Horton Barker, the blind singer from Virginia, Roscoe Holcomb, the well- digger from Kentucky, and Frank Proffitt, the farmer and carpenter from North Carolina, who "told us more than we have grown accustomed to expect . . . since a great many of us have come to equate folk music with cuteness, cleverness, and pretty sounds. . . . Often folksinging is not pretty. Sometimes it is harsh, as life itself is harsh. Always it is true. . . . There was a singular reaction at the three-day festival ... the audiences, consisting primarily of college students, acclaimed the Appalachian men rather than the slick pros.

On February 16, after returning home, Frank wrote, "I loved the people I met there and I spent a lot of time . . . talking to the fine young fellows about our mountains, the progress made in late years and some of the ways of other days. The boys and girls are serious about traditions of other peoples, I can see ... and have a high respect for homespunqualities. . . . Not one laugh was made at any errors of my speech or any other shortcomings I might have shown. These folks just aint looking for this sort of thing. ... It was almost spiritual in nature, and to have this experience is the greatest thing that has happened to me so far. . . ."

In Chicago Sandy Paton heard Frank for the first time. Later that year he took some sophisticated recording equipment down to Watauga County and recorded Frank Proffitt for Folkways Records - Frank Proffitt Sings Folk Songs (FA 2360). We were proud to write the notes for this album and grateful to Sandy for making this record possible for Frank. Frank wrote that he very much liked our notes for his record, "I am so proud you spoke of my kind of people, their ways and struggles ... I so much desire to only be a representitive of my kind of people, neaver to just exault myself . . . just to bring to this generation a little bit of the past and my own atti- tudes toward life. So I would not want a word changed, not even my own quotes which if not of correctness all is of sincerity . . . ." I so much desire to only be a representitive of my kind of people, neaver to just exault myself.

Not many months after the Folk- ways record, Sandy and Caroline Paton and Lee Haggerty decided to found Folk-Legacy Records, a label that has great importance to people interested in traditional music. Folk- Legacy's first issue, FSA-1, was by Frank Proffitt. It came out not long after Frank's Folkways album, so by 1962 two albums of Frank Proffitt's songs, sung by Frank, were available for those interested in traditional music, and many people were interested.[7]

Things had been happening to the Proffitt children. Ronald had been admitted to the Berea Foundation School for his last year of high school, and to Berea College for the following year. Oliver was advancing in the Air Force and was stationed at a big base in Spain. Frank wrote us in March, 1961, "Ronald won an essay contest and a $300 scholarship, and Phyllis won a trip to camp. . . . The Proffitts are getting in the habit of winning things, but what else can you do when you aint got money?"

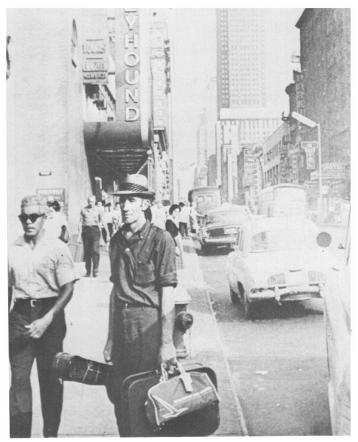

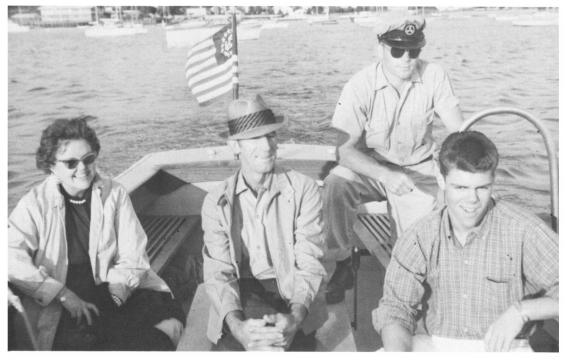

[Warner Photo: At the bus station. Frank Proffitt on his first visit to New York City. 1961.]

In August Frank made his first trip to New York City, coming in by Greyhound bus. Frank Warner met him and brought him out to stay with us on Long Island for a few days. Jinny and Reed Whitney, old friends of ours who had for a time owned the Brigantine Yankee (sailing young people around the world), were visiting Long Island in their Little Yankee and were anchored in Manhasset Harbor. We took Frank to have dinner with the Whitneys on board their yacht - his first time on the water.

[First time on the water. Frank Proffitt with Anne and Jeff Warner being ferried to sailing yacht on Manhasset Bay, Long Island. 1961. Warner Photo]

The next week the Warners and Frank spent as staff members at Pinewoods Folk Music Camp, run by the Country Dance and Song Society of America, near Ply- mouth, Massachusetts. En route to Pinewoods we had stopped by Old Sturbridge Village, the restored early New England village in Sturbridge, Mass., where Bill Bonyun and Art Schrader were resident folksingers and musicologists. They had invited Frank to sing on the Village Green, to a delighted audience. Visiting Pinewoods in 1961 were Douglas and Helen Kennedy, leading British folklorists. They were charmed by Frank, and he by them. Douglas Kennedy said of Frank, "the hills of Scotland are full of faces like his!" The Kennedys found impressive a song handed down in Frank's family which Frank recorded on the first Folk-Legacy album, "Bonnie James Campbell":

Booted and spurred

And bridled rode he,

A plume in his saddle

And a sword at his knee.

Back come his saddle

All bloody to see;

Back come his steed,

But never come he.

Riding on the highlands,

Steep was the way;

Riding in the lowlands,

Hard by the Tay.

Out come his old mother

With feet all so bare;

Out come his bonnie bride

Riving of her hair.

The meadows all a-falling

And the sheep all unshorn;

The house is a-leaking

And the baby's unborn,

But Bonnie James Campbell

Nowhere can you see

With a plume in his saddle

And a sword at his knee.

For to home come his saddle

All bloody to see;

Home come the steed,

But never come he.

Notable is the retention of old Scottish words in this song coming to Frank by oral tradition, and the reference to the River Tay. Sandy says in his Folk- Legacy notes on the song, "this [bal- lad] is extremely rare in tradition. . . . Child printed only four texts ... all from Scottish sources. . . . While all of Frank's verses appear in one or another of Child's texts, no single one of them is as complete as this. . . ."

While at Pinewoods Frank Warner taped a conversation between Douglas Kennedy, Frank Proffitt, and himself, with some songs by Frank Proffitt. Frank was proud to have a letter in September from Douglas Kennedy saying he was using the tape in his lectures in Britain. The Pinewoods campers took up a collection to buy a Proffitt banjo that week to present to the Kennedys as a parting gift, so one of Frank's banjos went back to England and, the Kennedys wrote, received much admiration.

On our free afternoon at Pinewoods we took Frank out on Cape Cod. In nearing Hyannisport we found certain roads blocked off because President Kennedy was at the Kennedy compound. Frank could not quite believe that he was that near the President. He said, with his characteristic chuckle, "When I get home if I tell people where I've been they'll say 'how that man can lie!' "

We stopped at a beach to see the ocean, and although there were no breakers and it was a cloudy day Frank had to take off his shoes and feel the sand and the water of the Atlantic between his toes. We had dinner at Bert's in Plymouth. Frank had swordfish, which he liked very much. Anne had a lobster, which Frank said looked to him like "a economy-size crawfish."

Writing us from home on August 30, "In thinking of my trip and of being with you and Anne and the boys, I understand more than ever all the things you have done for me, all of you. . . . The apprication I now feel toward all of you, even to little? Maggie [our exuberant German Shepherd named Lady Margaret, Little Maggie for short] is a deep feeling you can believe. I was awed with it all. ... I did not expect quite the regards that you held for me. However it all was good and I know there is no other mountain man that could recive such attention without no more than I have done."

Late in 1961 Frank wrote that he had heard from George Armstrong who wished to know if he, Frank, would plan to come to Chicago the next March for workshops at the Old Town School, programs at two or three schools or clubs, then to the University of Illinois - a tour which might bring him between three and four hundred dollars, plus a chance to get orders for banjos and dulcimers. "My writing you is simply I cant make a decision . . . because I feel this would be more than I might handle and I dont have the upper hand on my danged shyness yet. What do you think? Should I do this? Do I have enough to offer? Spare not my feel- ings. Help me if you can."

Frank Warner replied, after discussing whether the trip would interfere with Frank's farming or any possible local work and so cause him to lose money perhaps, "I know you would do all right at the workshops and programs . . . you have got to believe in yourself and your material. Your experiences at Chicago and at Pine- woods should prove you do OK in front of people. Nobody you see will be any better than the folks you already have performed for. ... I know about shyness and I sympathize . . . but you can overcome this. Who are you going to meet that is more import- ant than the Douglas Kennedys? Nobody you would see knows your stuff as well as you do ... nobody will be able to sing and play in your style. . . . if the money is good enough, I say go ahead. . . . Most of the time a fellow doesn't stretch himself to improve un- til he has to meet a challenge like this. . . ."

Frank's decision to accept this challenge, and the success of the venture, put him on the road. In 1963, a year later, after making several tours of this kind, he wrote, "I'm getting so I really enjoy a program now." On this first tour everyone showed the greatest appreciation, and he wrote, "I sang the old songs without instrument and they went over wonderful."

Sometime before, at Frank Warner's urging, Frank had begun to sing the old ballads ("Bo Lamkin," "George Collins," and others) unaccompanied. Before that he had sung all his songs to the chords he knew on the guitar (or the banjo) and the old modal tunes had suffered. Frank himself had been pleased and surprised at the way the music of the ballads came back to life.

Back home in April of 1962, and rested up, he wrote us about some interesting and amusing incidents:

I visited many fine cultured people in the great city of Chicago and I was amazed at their exceptance [acceptance] of me as a person. . . . The head of the Lake Forest School for Boys I had supper with is a great adapter of music from my level to high brow or stage and opera . . . he plans on doing music for some songs of mine, and as he told me he done this for Sandburg's "Chi- cago" and other poetry of him, I feel quite- flattered. . . . The train ride was great. I had a great time banjer talking with the conductor who is a Ky. man on the Knoxville-Cincinnati run. . . . My heart bled, though, at paying $3.85 for corn beef hash, and 35 cents for coffee and 85 cents for ham on rye grieved me sorely. When they priced the pull down bed for 6 hours at $13.50, well I bought a pillow and snored away on a seat. I still can stand on my head 6 hours for that money. I'm laughing yet at getting $100 travel pay and making a profit of $32.75. George thinks I have Scottish blood. Ha! I might ought not to tell this, but doggone it, money's hard to get in the spring. . . ."

June 4, 1962, "Miss Gay[8] sent me a fine letter today and a $50 advance on the trip to Pinewoods. . . . Sandy hopes I could come to Huntington [9] as a part of the Pinewoods trip, for a third recording. I don't know yet, all depends on what my employment would be at the time and the ripening of tobacco. George plans on doing a article of me and my domestic projects with photographs of surrondings hereabouts for Mountain Life and Work. He is now a member of the publication staff of the Council of Southern Mts. . . . Anne, the Beech folks are well. I am in the shop, or Bessie could put in a word. The kids are fast beanpoling up now. Gerald is about the only kid I have around. Ronald's taller than me, Frank is eye- to-eye, Phyllis is reaching for the sky. ... I do hope you get to suffering to come down plum bad, Anne, you and Frank. ..."

In July, 1962, Frank Warner wrote Frank about the settlement of the Tom Dooley case. He responded, "The news that the case was settled brings a sort of relief. ... I retain my thankfulness of what has come to pass for me. I don't think the Tom Dooley song will die completely. It is a ballad of sim- plicity representing a area and period of history of interest to many people. In that spirit I sang it to you and in that spirit you sang it for others. . . ."

Everyone enjoyed Frank's second year at Pinewoods, and Frank did too. It had been hard to make the decision to come, but it worked out well. He wrote on September 8, "All went well while gone. Tobacco will wait a few days yet to cut."

Many people ordered banjos and dulcimers, and his trip to Huntington was a delight. Lee Hag- gerty took him back to the mountains in his little sports car. "While the Pine- woods trip looked like a sort of set- back money wise . . . now I know I done wise to go not only in that . . . but I gained much in self confidence . . . and do hope most heartily that I didnt bring no disappointment to any- one. . . ."

While at the Patons Frank met Lawrence Older who came to visit. Larry, too, had made an album forFolk-Legacy. He is an Adirondack mountain man, a former lumberjack, a fiddler, and a singer of fine songs. He and Frank had much in common and became firm friends. Many things developed for the Proffits in 1962, to the point where Frank found it was going to be possible, perhaps the next year, for him to build a new house. He wrote us on November 6:

I think you and Anne would enjoy knowing what Bessie and me think of the things coming our way which to us is a miracle and we consider it of devine origin. . . . When things looked dark as it does to one who makes his living as I do . . . there is occasions in the winter when money runs out and no way in view. During the big snow last year was one of thease times. While some people might think a person who sings old songs, jigs . . . and messes around with banjers neaver prays, in this they are wrong in my case. While I dont pray any too often, when I do I do earnestly and with faith. On one of the nights of the big snow I awoke thinking about what I could do. I saw clearly the things I had wanted from the Tom Dooley case was selfish and small minded, so I just asked God for a way to live, a way for my children . . . not money, nesseserily, nor not confined to the Tom Dooley case. . . . A great peace come. From that day till now no doubts has arose but that there's a way for us all. It was not such a blow, the Tom Dooley failure. I had this peaceful assurance inside . . . and that peaceful assurance is now a fact. This letter with its reference to Devine help . . . is not to impress you and Anne that I feel I'm good or that some great change has occured to me in a spiritual way of late. I feel except for some miracles that happen in life spiritual things grow as cultivated. I know very much my weakness, my shortcomings, thease are many. I do hope to overcome more of them as I go along. . . . I look forward to learning more, hoping for new exsperience. It truly is a good way of life this under- standing we share. I am glad you brought me into it with you. . . ."

Some of the things that happened to the Proffitts can be told through excerpts from Frank's subsequent letters. November 13, 1962: "I am thrilled with The Little Sandy Review copy and have a deep apprication of the use of me in its main feature."[10]

November 15, 1962: "I am writing to let you know that Time Magazine has . . . photographed me for use in an article on folk music. [Later, there was a story about him in Life, also.] The Winston Salem Journal is running a story. ... As I see it, this is quite important in record sales, instruments, and general benefits. I think . . . part of the reconition enjoyed by the Kingston Trio is switching now. I hope I can handle it all and remain my own true self, a thing I will seek to do with all my heart.

December 26, 1962: "There is no need to say I was made happy with the check [some Tom Dooley royalties from TRO] ... I have a good plan for it, Ronald's second semester. . . . Some plans are in the making for me to make a concert tour ... to in- clude the University of Indiana, the University of Illinois, a day or two at Wilmette, then on by train or plane to a college in Vermont. . . . Should clear $500 with orders not counted . . . late March. Tobacco done quite well, about $750."

January 14, 1963: "I have recived a letter from J. C. Brown who is [now] the Executive Manager of the Tar Heel Electric Membership Association . . . to sing songs from my album at their annual banquet in Feb. Norman Clapp, National Administrator of the Rural Electrification Administration, will be the speaker. . . . This sort of overwhelms me. ..."

January 28, 1963: "Your letter combined with the check [some royal- ties from Broadcast Music, Inc.] is starting '63 off mighty good I can tell you. . . ."

February, 1963: "My tour has increased to more concerts. It looks now as if I might be away 3 weeks and could clear $1000 or a little more "

February 11, 1963: "I was some- what elated and surprised to get copies of the Readers Digest with the con- densation of the Time article. . . . Ron- ald has passed with excellent ratings. 3 As and 3 Bs. ... He has decided to major in physics. ... As I told you, the house site has been fixed. When weather permits I shall start the house. ... I have hopes of getting a all-elec- tric deal as a demonstrator home, so my heating cost . . . would be a guaranteed rate. I plan to build the house myself. . . ." The letter of April 18 enclosed a fine article by Jim Keith in The State, a North Carolina magazine.

April 23, 1963: "I've not told you of late about my dulcimer making and banjers. I have more difficulty keep- ing orders filled now than ever. ... I have worked out a faster set up, as this is important income for me." About his tour in March, "I enclose some articles of me at the concerts. . . . Really I went over big - excuse my modesty! I sung and talked as to a person. ... I forgot myself in trying to put over the ones who sing to me. ... I was treated deeply and sincerely. . . . When I was in Champaign, Ill. I was photographed and reviewed a day before the concert. Next day my picture come out playing a dulcimer. The title was 'Hill Billy singer plays his frettless banjo.' That night I told them I had progressed to a hill billy so fast I hadn't time to get a cowboy rig, and that the mountain wimmin would kill me if they thought I'd called a dulcimer a banjer. This brought plenty of laughs."

May 29, 1963: "I was flabbergasted with a offer that's come from Wesleyan College, Macon, Ga., that you had told me about. Five Hundred dollars? Whew! I certainly appricate your recomindation."

This was an invitation to be part of an annual Arts Festival, including programs on art, music, drama, etc., to be held in April of 1964. In June of 1963 we met Frank and Bessie in Asheville where Frank Warner and Frank Proffitt participated in the Asheville Folk Festival, produced by James Morris. Our dear friend Buna Hicks was part of it, too. Among others who were there were Alan Lomax, Pete Seeger, Doc Watson, Horton Barker, John Jacob Niles, Sonny Terry, Ed Young, Jean Ritchie, and Hobart Smith.

July 17, 1963: "The North Caro- lina Travel Information Division is adding a folklore addition to their tourist folder called Variety Vacationland. A picture of me in color will headline this. ... I dont know if ... I want to be a 'scenic wonder!' A letter come from the University of California, the Idyllwild Arts Foundation, asking Bessie and me to come the first two weeks of July next year, to teach a class how to make a frettless banjer. . . ."

Also in the summer of 1963 Frank went to the National Folk Festival in Kentucky where he received the Burl Ives Award for his traditional banjo playing. In August, 1963, Frank wrote: Enclosed you will find some pictures taken last Sunday in Happy Valley. We was invited to go down with some friends who previously had been there. The valley is very pretty with behind the times look, and in going up the valley I was impressed when we passed three Dula mailboxes and a Dula grave yard. . . . We went from there to Ridge country. . . . 4 or 5 miles wandering off on narrow roads. At last, driving out on a meadow knoll at a big oak in the meadow which was fresh mowed was Tom's grave. We spent some time there under the oak, eating lunch also. One could not think of murder or sordidness amid the quiet peaceful solatude. The views of low lying hills, the distant mountains and valley below would not allow this for me. There is a dignity to a grave, and while I knew Tom reprisinted the instability of emotions of mtn. folk, one knows this also brought reconi- tion of much degree to the mountain ballad singers all over. . . . One canunderstand why a song could come from such a happening. The hills, the valley, and all combined gives one a desire to sing or tell something thats neaver been told before. It was good to think of Tom roaming as a boy hereabouts in youthful innocents and of Laura following the path to the spring house for the milk crock. . . . I somehow think Tom will appricate my thoughts of him.

[I sit as no judge by a man's grave. But allow him to exsplain the why to a merciful God.]

The strange mysterious workings which has made Tom Dooly live is a lot to think about. Other like affairs have been forgotten. I feel sure you know and I dont have to exsplain that l dont ignore the lack of morals in this matter of long ago. My preference is to believe the old tale, that Tom was meek and repentant, rather than the sensational writers of that day with fiendish brazen braggart pictures. Tom was a personality I feel, weak, easily led. The best that could be said is he didnt conform to rules. I sit as no judge by a man's grave. But allow him to exsplain the why to a merciful God. I have my picture, others can have theirs. For he was one of the mountain folk, and did cridit to himself singing among the homesick North Carolina Rebels during the war. . . ."

On September 27, 1963, after tell- ing of banjo orders, "I get funny let- ters ... for example I got this: 'I hear you make banjos. Could you tell me if they cost anything or not? I would like to have one if they don't cost any- thing, or ... if they do cost something but not much.' "

[I am glad I saw the dunes of Hyannisport and the sandy beaches of Cape Cod]

On October 5, 1963, after he had received his copy of the magazine with Frank Warner's article, "Sing Out! arrived today and I would neaver amagined you could have seen so much in us. I doubt if there is anywhere such a close bond between collector and informer .... There is such a demand for my records now in this area. Just yesterday alone 6 people come from Boone and bought 8."

On December 6, 1963, Oliver got an airlift, Frank wrote, and came home from Spain for two weeks. About President Kennedy's death, "I am glad I saw the dunes of Hyannisport and the sandy beaches of Cape Cod. . . ."

December 30: "We had some visitors .... Earl Scruggs and his wife, and Dr. Nat Winston, head of the Mental Health Division of the State of Tennessee. He is interested in folk music."

January 27, 1964: "The weather has been extreamly bad ... the finish work on the house depends on weather conditions. . . ."

March 2: "I am getting much response for records from the Scenic Wonder picture .... I got a request from the head of Duke's Medical staff for instruments . . . ."

March 21: "I have excepted to go to the World's Fair in New York on June 2 for North Carolina Day." Later, on May 15, he wrote about arrangements made for his coming from Raleigh by bus with other par- ticipants on June 1 . "By the way, that's my birthday. I couldnt foresee this oc- casion when I first met you both at Nathan's. I have a right to be awed, dont you think?"

June 2, 1964, was warm and sunny. We met Frank at the Fair Grounds in Flushing, New York, in Queens County, Long Island. The celebration of North Carolina Day took place outdoors on a large low stage with chairs all around. Participants included the Honeycutt Twins, teenaged boys from Mitchell County who played a guitar and a banjo and sang songs old and new; The North Carolina Military Academy Dance Band; Richard Crowe, a Cherokee Indian who played a leading role in the outdoor drama in Cherokee, N.C., "Unto These Hills"; Lydia Fish, a singer from Chapel Hill;Tom and Dave Whitty, fifteen-year-old singers from New Bern; The Blue Ridge Mountain Dancers; and Frank Proffitt. The Dancers, teen-age boys and girls who have turned the traditional individual clog dance into an electrifying group performance, filled the whole area with the loud rhythms of their pounding feet on the wooden platform. They were a delight. The sound brought people scurrying around to see about the excitement. This insured a large crowd for Frank Proffitt's part, and he didn't let his audience down. Frank Warner introduced him and he took over. It was a proud time.

On June 13, back home, Frank wrote, "I wont forget soon our ex- periences at the Fair as well as your welcome at your home. . . . Gov. San- ford sent me a Distinguished Citizen Award which I am proud of." Before the Fair, in April, he made his trip to Macon and enjoyed it so much he agreed to go back to Georgia in May to the University of Athens. "The money is not as good as Macon but still beats snapbeans at 50C a bushel! . . . Another concert [I have been asked to do] is the Governors School for outstanding high school students at Raleigh. ..."

Later, "I find myself in a position more and more as a source of information of what the problems of mountain people really are ... behind the scenes."

In July of 1964 Frank participated in the Newport Folk Festival, and Bessie, in spite of a recent operation, was able to come with him. After the festival we brought them home to Long Island for a visit - the only time we were able to have Bessie with us. We showed them something of the city and rode the Staten Island Ferry and saw the ocean at Jones Beach. In October we went south to see our sons Jeff and Gerret at Duke University and then spent some time with the Proffitts who had moved into their new home. Frank had done it all himself, with some help from his sons, except for plumbing and wiring. He figured his work on the house, if he had paid someone else to do it, would have cost more than $8,000. It was, and is, a beautiful house - tasteful and simple and comfortable. Bessie had had another operation, this time on her feet which were both in casts while we were there, but she was her cheerful loving self.

[Warner Photo The Proffitt and Warner children on the porch of the second house Frank Proffitt built for his family. 1951.]

In September there was a long feature story about the Proffitts, with photographs, in the Watauga Democrat. December 9, 1964: "I got an inter- esting letter the other day from Wisconsin .... Bill Parson, age 25, single . . . offered to come work a year, staying with me without wadges and me learn him how to play the frettless banjer and be a mountain folk singer. The offer attracted me as I could sitin the shade . . . while he hoed tobacco .... I dont have the heart to cheat fellow humans so badly so I had to refuse . . . ."

Somewhere along the way Frank and Bessie sent us a special country ham. As a matter of fact we had asked him to get it for us, but he wrote, "In today's mail I am sending you all a ham. This is a year old or better, coming from Tripplett, the Post Office sawmill farmer and ham man I told you about. I took two down from the log house rafter myself .... A little off taste Rind still may remain [after trimming] but wait till you hit the center .... In the two trips to Pine- woods I seen your and Anne's pleasure in treating me good along the road up there in the form of good meals, etc. I have bided my time and have the same pleasure now to do a little for both of you. I dont expect you to be selfish and not let me have my pleasure and Bessie hers, but except [accept] this ham with no arguments . . . ."

In reply Frank Warner composed a few verses parodying the old song:

Well I'm going down the street

Gonna get me a ham of meat

Gonna keep my skillet greasy all the time.

Here they are:

That Good Old Mountain Ham

Well I got me a ham of meat

It's the best I ever eat!

I'm gonna keep my skillet greasy

All the time, time, time,

Gonna keep my skillet greasy

All the time.

When I hear that meat a-fryin'

You can see my feet a-flyin'

I'll be singing "Blackjack Davy"

When I get my grits and gravy . . .

Meat for folks, bone for dog,

Warners living high on the hog . . .

Every time I taste that ham I think of good old Beaver Dam.

Every time I get a mess,

Send my love to Frank and Bess

Gonna keep my skillet greasy all the time!

Frank Proffitt was not outdone. In fact, he outdid Frank Warner:

The Greasy Skillett or,

MOUNTAIN HAM NO. 2

(Watch Capital Records)

News has come as you can guess

Both to Frank and unto Bess

About how your skilletts Greasy

All the time, time, time,

About how your skillets Greasy

All the time.

News is good of Frank and Anne

Huddled around the fryin' pan

Keeping the skillet greasy

All the time . . .

As we sing of hams and grits

We might start a batch of hits

Just to keep our skillett

Greasy All the time . . .

But as we sing of ham and lard

We must watch about Dave Gard [11]

Or he'll have his skillet greasy

All the time . . .

For Dave he haint no fool

He's the one who swiped Tom Dool

And has a greasy skillett all the time . . .

Any time you want a ham

Drop a line to Beaver Dam

And keep that skillet good and Greasy

all the time.

January, 1965: "Looks like I'll have a big concert for the Methodist Medical and Ministers Conference at [Lake] Junaluska - 1500 people - with the Jordanaires."

About this time Folk-Legacy Records brought out a recording of Ray Hicks - Bessie's brother- telling Jack Tales, and there was a good deal of interest in it. Frank had become exclusive Southern distributor for Folk-Legacy Records, so he was selling them all wherever he could, some in the Handcraft Shops at Roaring Gap and Blowing Rock for the tourist trade.

February 19, 1965: "I have been granted $2500 under the Economic Aid Program for the perpoise of building a woodworking shop and its equipment. The Supervisor knows me quite well and has spent some visits in theold sñop .... ne also has deep interest in folk music. This is a promissory note arrangement at low interest over a 15 years period - a encouragement of home enterprises . . . you might say anti-poverty."[12]

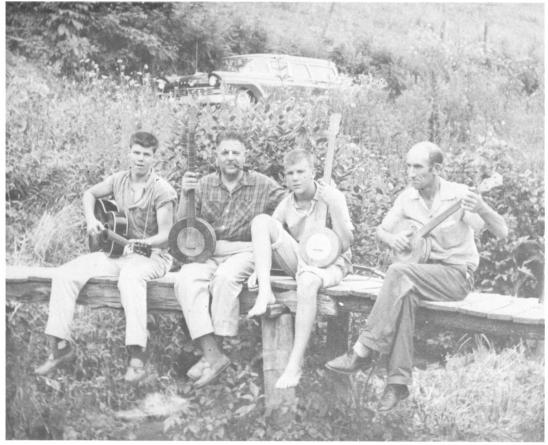

Also, "Frank Jr. is coming along so well with his music I am considering including him in some of my programs .... it's becoming to be a matter I feel not to help him but his helping me." Phyllis had married Lee Hicks the year before, and in the spring of 1965 Charlie was born, to everyone's de- light. Oliver, still stationed in Europe, had married Rita, a German girl, and the Proffitts welcomed her by letters.

And Ronald: "Boy, we had great news today. Ronald wrote that Dr. Weir of the University of Kentucky telephoned him that the Aeronautics & Space Ad- ministration had chosen him for a 3- years Fellowship - $2400 a year - for a masters degree in physics, with a possible PH D .... We are very happy."

March 26: "I have a offer to sing at Appalachian State with Doc Watson, M. C. is Cratis Williams. Cratis dont like anything in song younger than 300 years it seems, so Doc and I will have to be careful!"

April 12: "The weather is getting nice. I got my tobbacco bed sowed . . . and still am going ahead with a better shop set up soon. I reckon I will use the old house [his father's house, behind him and up the hill] since its already built and away from hustle and bustle .... if certain folknics arrive and they dont look to suit me I can dash in the laurels. Ha! I've scrape up enough money and cridit to put in some extra bench power tools. Now I can be as poor or as rich as I can make out of it without worry- ing the government which has enough worry s without me adding to it."

May 10, 1965: "Frank Jr. and I have just arrived back from Berea College where we done the concert. Frank was a smash in his versertility in dulcimer playing. We done some together aliso. His first concert money will be $100 [his share of Frank Sr.'s fee]. Fit to bust is mild. . . . We both autographed many sheets - Frank B. and Frank N. If Frank B. starts cutting too deeply into my prestige I suppose I'll have to find some way to take him down a few notches! Ha."

Both Ronald Proffitt and Jeff Warner graduated that June, Ronald from Berea and Jeff from Duke. June 2: "I was just thinking the other day how strange it is but happy, so when something eventful happens to one of our familys the same thing comes along for the other. Ron and Jeff this year. I get choked up with gratitude sometimes because of it. This has been going on sometime too ... ."

Frank Jr. graduated from high school in June, and though he was accepted at Appalachian State, he decided to get a job for a year at least. In July Frank wrote, "We will try to send a picture of Charlie soon .... I dont recall Bessie or any other member of my family looking at me since this little rascal arrived. Somehow I dont mind. I dont look at them either. Charles I is king . . . ."

[From left to right: Jeff, Frank, and Gerret Warner, and Frank Proffitt, on the foot- bridge leading from the road to the Proffitt house. 1959. Warner Photo ]

There was much correspondence in the summer of 1965 over the hope that Frank could come back to Pinewoods to help celebrate the Country Dance and Song Society's 50th anniversary. Miss Gadd offered Bessie hospitality too, and a scholarship to Frank Jr., but in the end, after deciding one way and then the other, Frank decided it was not possible. Bessie was wearing a back brace to help correct a painful condition, Frank Jr. had a job, and Frank himself was not feeling very good and was having treatment twice a week at the hospital. It was nothing serious, he said. Good news was word of the arrival of Jeffrey Franklin, son of Rita and Oliver.

September 15, 1965: "I've been interviewed for a story for the Atlanta Constitution, and was invited to the Atlanta Festival at Helen, Ga., but I was too busy to go. If I had and seen Jeff wouldnt that have been great!"[13] In the summer Frank Proffitt had written a long letter to Sing Out! magazine and they decided to publish it, and even to pay him a small amount for it, though this is not their usual custom. Frank sent us a copy with some notes: "This is the letter - article - that will appear in Sing Out! . . . not intended for this but excepted anyway. I broke out in poetry when I heared I was to get money and a song resulted - to the tune of 'When I was single, my pockets they'd jingle.' "

I am a writer, I am, I am I am a writer, I am I am a writer, well I'll be dogged, I am a writer, I am!

On October 6 Frank Warner wrote Frank, (Sing Out! came Saturday and we rushed to read your article. It is a splendid piece of work and we are very proud of it and of what you say of us. I am sure it will be read with much interest and appreciation by a lot of people . . . ."

We had a very brief note written on November 13, just a few sentences. It did not sound like Frank at all, and we wrote asking if he was all right. Our last letter from Frank is post- marked November 20, 1965. This was two pages long and sounded much more normal, but, no doubt in reply to our questions, he wrote, "As to my- self, I am not having any unusual problems. I dont cast off worrys as well as I use to I notice. I do my best when concentrating on work projects."

He mentioned a recent visit from John Cohen and his wife Penny and their little daughter. "John is doing a banjer tuning record project and I contributed some old tunings to this." Then he wrote, "Tomorrow, the 21st, I take Bessie to Charlotte for an additional operation on one of her feet. This may require 10 days stay there."

On Thanksgiving morning, November 24, a neighbor of the Proffitts telephoned to tell us that Frank had died. He had taken Bessie to Charlotte, as he wrote us he would do, then he had driven back home, gone to bed, and had not waked again. His going so suddenly, and at the age of 52, was a blow to everyone in the country who had known him or known of him. All the family - Bessie, brought back from the hospital with her foot in a cast, T/Sgt. Oliver, on leave from the Air Force in France, Ronald, from the University of Kentucky, Frank Jr., Phyllis and her family, Eddie, Gerald- and relatives and friends gathered at the Bethel Church on Sunday, November 28, for Frank's services, and then he was buried in the small private Milsap burying ground high on a hillside about a mile from his home.

In January of 1966 there was a Memorial Concert for Frank Proffitt at Hunter College in New York City, to pay tribute to a friend and colleague, and to raise money to pay off the mortgage left on the house. The Newport Folk Foundation helped organize details, the Harold Leventhal office handled the promotion and sale of tickets. As Frank Warner said in his report of the concert to interested friends and contributors, "All of us who participated knew and loved and respected Frank Proffitt and, I think, felt the need to state our feelings openly when he left us so suddenly."

Singing that night were Jean Ritchie, Pete Seeger, Sandy and Caroline Paton, Doc Watson, the New Lost City Ramblers, and Frank Warner. Quoting again from the report, "It was an informal, warm atmosphere all through. Nobody was putting on the act. . . . Everyone was there because he wanted to be. The audience gave complete and rapt attention and the warmest possible response. Frank would have liked it .... At the end all the participants joined in singing 'Amazing Grace.' Doc Watson led off and Jean Ritchie lined it out, and the audience joined in ... and it was very moving and very fine."

Through many dangers toils and snares I have already come

'Twas Grace that led me safe this far

And Grace will lead me home.

And now? Oliver is a Master Sergeant, with two children, soon to return for a tour of duty in the States. Tragically, in 1971, Ronald, having achieved his doctorate and having married Wanda, a fellow student, just a month before, was on his way to his first teaching post in Illinois when he was killed in an automobile accident. It reminded us of Frank's talking from time to time of the many tragedies that had come to his neighbors and his kinfolk in the mountains - tragedies such as he identified with in his old ballads. Frank Jr., his wife Nell, and their two little boys are doing well and Frank is keeping up with his music.

In 1969 Frank Warner had the pleasure of introducing him at the last Folk Festival in Newport where he got a standing ovation. He has a job, but he takes singing engagements whenever they turn up. His daddy would be proud. Phyllis and Lee and their two boys live near Bessie. Eddie and his wife Paulette live in Boone. Last year Gerald graduated from high school. Bessie is courageous and loving, and a dear friend. In 1967, with the help of many friends of Frank Proffitt, we raised the money to put up a headstone at Frank's grave. It is a simple granite marker, befitting Frank's character. It says:

FRANK NOAH PROFFITT

1913-1965

GOING ACROSS THE MOUNTAIN

O, FARE YOU WELL

Mountain people are reserved. Frank Proffitt was reserved. He had no small talk. We sometimes sat with him for a long time without a word being spoken, but there was no break in communication. Afterward we would realize how urban living has filled up all the white spaces in life, leaving little chance for solitude or thought. Mountains encourage thought, and with Frank they had their way. Frank was strong, in character and in body. The kind of farming and hard work he had to do all his life make a man strong, if he doesn't give in.

[Going Across the Mountain. O, Fare You Well.]

Frank didn't give in. He had faults, as he always insisted on stating. He was proud, and he took offense if he felt he was being treated unfairly. But usually, on second thought, his compassion and humor came to his rescue. If he was proud, it was of his mountains and his forebears who came from across the water, settled the land, felled the trees, broke the new ground, kept their songs and traditions, helped build the country. We can all be proud.

Beaver Dam Farm

Old Brookville, New York

NOTES

1 "Dan Doo" is on Folkways Album FA 2360; "Moonshine" and "Tom Dooley" on Folk-Legacy Album FSA-1.