The Great South: An Excerpt

By Edward King 1874

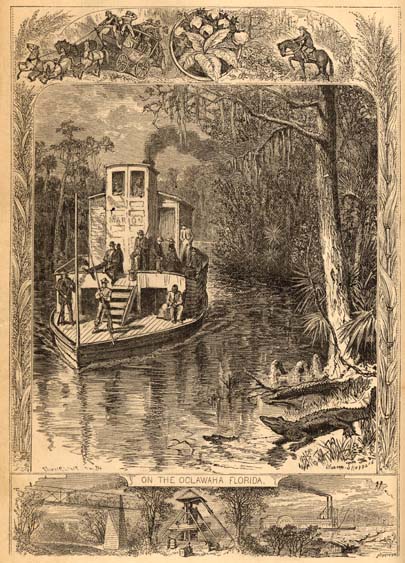

[This is an excellent book describing in detail the US south in the post Civil War era. The excerpt here is Chapter 68 "Negro Songs and Singers." Published in 1975 this is one of the early publications of texts.

There are some excellent illustrations (like the frontispiece below). The entire book has been digitized and is available on-line. R. Matteson 2011]

The Great South; A Record of Journeys in Louisiana, Texas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland:

King, Edward, 1848-1896

LXVIII

NEGRO SONGS AND SINGERS

THE negro would deserve well of this country if he had given it nothing but the melodies by which he will be remembered long after the carping critics who refuse to admit that he is capable of intellectual progress are forgotten. His songs of a religious nature are indisputable proofs of the latent power for an artistic development which his friends have always claimed for him. They are echoes from the house of bondage, cries in the night, indistinct murmurs from an abyss. They take directly hold upon the Infinite. They are sublimest and most touching when they partake of the nature of wails and appeals. They have strange hints and gleams of nature in them, mingled with intense spiritual fervor. In this song, which the toilers in the tobacco factories of Virginia used to sing, there is a wild faith, and a groping after the proper poetry in which to express it, which touch the heart:

"May de Lord — He will be glad of me,

In de heaven He'll rejoice;

In de heaven once, in de heaven twice,

In de heaven He'll rejoice.

Bright sparkles in de churchyard,

Give light unto de tomb;

Bright summer, spring's ober,

Sweet flowers in de'r bloom."

This is the incoherence of ignorance; but when sung, no one can doubt the yearning, the intense longing which prompted it. The movement of the melodies is strong and sometimes almost resistless; the rhythm is perfect; the measure is steady and correct.

But little idea of the beauty and inspiration of the "slave music" can be conveyed by the mere words. The quaintness of the wild gestures which accompany all the songs cannot be described. At camp-meetings and revivalgatherings the slaves give themselves up to contortions, to stampings of feet, clappings of hands, and paroxysms affecting the whole body, when singing. The simplest hymns are sung with almost extravagant intensity.

ENTHUSIASM OF NEGRO SINGERS

The songs are mainly improvisations. But few were ever written; they sprang suddenly into use. They arose out of the ecstasy occasioned by the rude and violent dances on the plantation; they were the outgrowth of great and unavoidable sorrows, which forced the heart to voice its cry; or they bubbled up from the springs of religious excitement. Sometimes they were simply the expression of the joy found in vigorous, healthy existence; but of such there out"—that is, each line is read by the deacon or preacher, and then sung by the congregation; but this is quite unnecessary, as all are usually familiar with the words. In hymns and songs which are purely enthusiastic, the lines are never read; the worshipers will sometimes spontaneously break into a rolling chorus, which almost shakes the rafters of the church. Then their enthusiasm will die away to a tearful calm, broken only now and again by sobs and "Amens!" The appended hymns, sung in seasons of great enthusiasm by the negroes in and around Chattanooga, Tennessee, will serve to indicate the character of all of that class:

"Oh, yonder come my Jesus,

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

Oh, how do you know it's Jesus?

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

I know Him by his garments,

I know him by his garments.

His ship is heav-i-ly loaded,

His ship is heav-i-ly loaded,

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

It's loaded wid bright angels,

It's loaded wid bright angels,

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

Oh, how do yo' know dey are angels?

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

I know dem by deir shining,

I know dem by deir shining,

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

* * * *

"O, John! my Jesus' comin',

He is comin' in de mornin';

Jesus' comin'; He's comin' by de lightning,

Jesus' comin'; He's comin' in de rainbow.

Don't you want to go to Heaven?

Jesus' comin."

* * * *

"Oh, rock away chariot,

Rock all my crosses away;

Rock me into de Heavens.

I wish't I was in Heaven—

I wish't I was at home.

I wish't I was in Heaven —

Lord, I wish't I was at home!"

The pilgrimages of the "Jubilee " and Hampton singers through this country and England, and the brilliant success which attended their concerts, is a notable event in the history of the American negro. When the Jubilee Singers first went North to earn money for the University which was giving them their education, they met with some slights—were now and then called "niggers" and "negro minstrels," and were variously scoffed at. Here and there in the North and West they were refused admission to hotels on account of their color; their success was at first a matter of doubt; but their mission pleaded its way into the hearts of men when the sweet melodies and wild burdens of their

THE ''JUBILEE" AND "HAMPTON" SINGERS

songs were heard. In all the great cities of the North their concerts were attended by large audiences; Henry Ward Beecher welcomed them in Brooklyn, introducing them to his congregation at a Sunday evening prayer-meeting, when they sang some of their most effective songs; and straightway thereafter they were the rage in the Metropolis as well as in Brooklyn. Their tour through the Eastern States was productive of much profit, and the little band of singers carried home twenty thousand dollars to place in the treasury of Fisk University, as the result of their first campaign in the North.

Encouraged by this success, Prof. George L. White, who originally conceived the idea of teaching these emancipated slaves to sing the plantation hymns of the old times, and to give a scries of concerts embodying them, took the singers to England. All the world knows how enthusiastically they were received in Great Britain. The Queen, the nobility, and the great middle class heard them sing, gave them kind words and money, and praised them highly; and in March of 1874 this little band of blacks had collected ten thousand pounds, to'be used to pay for the building of Jubilee Hall, at the University at Nashville. Of the eleven singers, eight arc emancipated slaves.

The Hampton Student Singers at first numbered seventeen. They made their first appearance in 1872, under the direction of Mr. Thomas P. Fenner, of Providence, Rhode Island, who was of peculiar service in aiding them to a faithful musical rendering of the original slave songs. The singers were all regular students of the Hampton Normal Institute, and, even while journeying on their concert tour, carried their school-books with them. Their songs were heard with delight throughout the Middle, Eastern, and Western States, and their concerts have been attended with financial success.

The spirituality, the pathos, the subtle plaintivencss of the fresh, pure voices of these bands of black singers, invest the commonest words with a beauty and poetry which cannot be understood until one hears the songs. Once while listening to the singing of "Dust an' Ashes," one of the sweetest and sublimest chorals ever improvised, I tried in vain to analyze its mysterious fascination. The words were few and often repeated; the melody was from time to time almost monotonous. I could not fix the charm; yet the tears stood in my eyes when the wild chant was over,—and I was not the only one of the large audience gathered to hear the singing who wept. I give some of the words; but they will hardly serve to convey to the reader's mind any idea of the beauty of the choral:

"Dust, dust an' ashes

Fly over on my grave.

Dust, dust an' ashes

Fly over on my grave, (bis)

An' de Lord shall bear my spirit home, (bis)

Dcy crucified my Savior

And nailed him to dc cross, (bis)

An' de Lord shall bear my spirit home.

He rose, he rose,

He rose from de dead, (repeat)

An' dc Lord shall bear my spirit home."

SPECIMENS OF SPIRITUAL SONGS

One of the most effective of the spiritual songs is "Babylon 's Fallin','' which is often used at Hampton Institute as a marching song. The words are as follows:

"Pure city,

Babylon 's fallin' to rise no mo'.

Pure city,

Babylon 's fallin' to rise no mo'.

Oh, Babylon 's fallin', fallin', fallin',

Babylon 's fallin' to rise no mo'.

Oh, Jesus tell you once befo'

Babylon 's fallin' to rise no mo';

To go in peace and sin no mo'—

Babylon 's fallin' to rise no mo'."

Another note of aspiration is sounded in the hymn "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" the music of which is full of earnest prayer:

"Oh, swing low, sweet chariot;

Swing low, sweet chariot, (bis)

I don't want to leave me behind.

Oh de good ole chariot swing so low,

Good old chariot swing so low,

I don't want to leave me behind."

Even the religious hymns and songs are not devoid of that humor with which the negro is so freely endowed, and some of the words to hymns intended to be of the most serious character are highly ludicrous, as when we are informed, concerning a " pore sinner," that

"Vindictive vengeance on him fell,

Enough to sqush a world to hell;"

or when we hear a hundred negroes loudly singing—

"Jesus ride a milk-white hoss,

Ride him up and down de cross—

Sing Hallelujah!"

It is difficult to repress a smile when listening to the story of the deluge and Noah's voyage, as detailed in the popular choral hymn entitled, "De Ole Ark a-Moverin' Along." The last verse will give the reader a taste of its quality:

"Forty days an' forty nights, de rain it kep' a fallin',

De ole ark a-moverin', a-moverin' along;

De wicked dumb de trees, an' for help dey kep' a callin',

De ole ark a-moverin', &c,

Dat awful rain, she stopped at last, de waters dey subsided,

De old ark a-moverin', &c,

An' dat old ark wid all on board on Ararat she rided,

De old ark a-moverin', &c.

CHORUS—Oh, Ac ole ark a-moverin'," &c.

LAUGHABLE SONGS — HINTS AT DELIVERANCE

A hymn called the "Danville Chariot," which is very popular with the negroes in Virginia, has this verse:

"Oh shout, shout, de deb'l is about;

Oh shut yo' do' an' keep him out;

I don' want to stay here no longer.

For he is so much-a like-a snaky in de grass,

Ef you don' mind he will get you at las',

I don' want to stay here no longer.

Chorus—Oh, swing low, sweet chariot," &c.

The quaintness of the following often induces laughter, although it is always sung with the utmost enthusiasm:

"Gwine to sit down in de kingdom, I raly do believe

Whar Sabbaths have no end.

Gwine to walk about in Zion, I raly do believe,

Whar Sabbaths have no end.

Whar ye ben, young convert, whar ye ben so long?

Ben down low in de valley for to pray,

And I ain't done prayin' yit."

"Go, Chain de Lion Down," is the somewhat obscure title of a hymn in which this verse occurs:

"Do you see dat good ole sister,

Come a-waggin' up de hill so slow?

She wants to get to Heaven in due time,'

Before de heaven doors clo'.

Go chain de lion down,

Go chain de lion down,

Befo' de heaven doors clo'."

Many years before the period of bondage was over, and when it seemed likely to endure so long as the masters pleased, the negroes hinted in their hymns at their coming deliverance. They often compared themselves to the Israelites, and many of their most touching songs have some allusion to King Pharaoh and the hardness of his heart. A few of the more noted of the songs, which were the outgrowth of the negro's prophetic instinct that some day he should be free, are still sung in the churches and schools. This is a favorite among the blacks:

"Didn't my Lord deliber Daniel,

Didn't my Lord deliber Daniel,

And why not ebery man?

He delibered Daniel from de lion's den,

And Jonah from de belly of de whale,

An' de Hebrew children from de fiery furnace,

And why not ebery man?"

ANALYSIS OF THE NEGRO'S "HEART-MUSIC"

"Go Down, Moses," was another warning of the "wrath to come," which those in power did not soon enough accept. It was sung at many a midnight meeting, when the masters did not listen; and the oppressed took comfort as they joined in its chorus. The free children of parents who were born in slavery will look upon this song with a tearful interest:

"When Israel was in Egypt's land,

Let my people go;

Oppressed so hard dey could not stand,

Let my people go.

Go down, Moses,

Way down in Egypt land,

Tell ole Pha-roh,

Let my people go.

"Thus saith de Lord, bold Moses said,

Let my people go;

If not I'll smite your first-born dead,

Let my people go.

Go down, Moses," &c.

"No more shall dey in bondage toil,

Let my people go;

Let dem come out wid Egypt's spoil,

Let my people go.

Go down, Moses," &c.

The "first-born" have indeed been smitten, and Israel has come up out of Egypt.

Mr. Theodore F. Seward, of Orange, New Jersey, in his interesting preface to the collection of songs sung by the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University, makes the following remarks, which may help to a proper comprehension of the negro's heart-music:

"A technical analysis of these melodies shows some interesting facts. The first peculiarity that strikes the attention is in the rhythm. This is often complicated, and sometimes strikingly original. But although so new and strange, it is most remarkable that these effects are so extremely satisfactory. We see few cases of what theorists call mis-form, although the student of musical composition is likely to fall into that error long after he has mastered the leading principles of the art.

"Another noticeable feature of the songs is the entire absence of triple time, or three-part measure, among them. The reason for this is doubtless to be found in the beating of the foot and the swaying of the body which are such frequent accompaniments of the singing. These motions are in even measure, and in perfect time; and so it will be found that, however broken and seemingly irregular the movement of the music, it is always capable of the most exact measurement. In other words, its irregularities invariably conform to the 'higher law' of the perfect rhythmic flow.

"It is a coincidence worthy of note that more than half the melodies in this collection are in the same scale as that in which Scottish music is written; that is, with the fourth and seventh tones omitted. The fact that the music of the ancient Greeks is also said to have been written in this scale suggests an interesting inquiry as to whether it may not be a peculiar language of nature, or a simpler alphabet than the ordinary diatonic scale, in which the uncultivated mind finds its easiest expression."

THE "SPIRITUALS" — HOW THEY WERE PRESERVED

The teachers attached to the educational mission of the Port Royal Islands carefully studied the music of the half-barbarous negroes among whom they were stationed, and the result was an excellent collection of slave songs, which, without their efforts, would have been entirely lost.

The old planters sometimes say, with a shake of the head and a frown, that the negroes no longer sing "as they used to when they were happy." It is true that the freedmen do not sing as of yore; that they sing as much, however, there is little doubt. We have seen that the better class of their songs is filled with a vein of reproachful melancholy, that it everywhere has the nature of an appeal for help, a striving for something spiritual, dimly seen, and but half understood. These were the songs which the slaves sung at their work, but since their emancipation they are no longer compelled to voice their talents in such sombre music. The Port Royal teachers took down from the lips of the colored people hundreds of songs whose crude dialect and cruder melancholy rendered the task very difficult.

According to the testimony of the teachers the negroes always keep exquisite time in singing, and readily sacrifice a word and the sense attached to it if it stands in the way of the rhythm. The voices have a delicate and mellow tone peculiar to the colored race. There is rarely part singing, as it is not generally understood, and yet the Port Royal teachers say that when a number of blacks are singing together no two appear to sing the same thing. The leaders start the words of each verse, improvising many tunes, and the others, who "base" him, as they call it, will strike in with the version, or when they know the words, will join in the solo. They always succeed in producing perfect melody, out of whose network the transcribers have found great difficulty in extracting sounds that can be properly represented by the gamut.

The teachers testify that "the chief part of the negro music is civilized in its character, partly composed under the influence of association with the whites, and partly actually imitated from other music; but," they add, "in the main it appears to be original in the best sense of the word." Passages in some of the songs are essentially barbaric in character, and the teachers believe that most of the secular songs in use among the negroes contain faint echoes from the rude music of the African savages. A gentleman visiting at Port Royal is said to have been much struck with the resemblance of some of the tunes sung by the watermen there to boatmen's songs he had heard on the Nile. Colonel Higginson, who spent some time among the negroes on the South Carolina islands, gives a curious description of the way in which negro songs were originated. One day, as he was crossing in a small boat from one island to another, one of the oarsmen, who was asked for his theory of the origin of the spirituals, as the negroes call their songs, said, "Dey start jess out o' curiosity. I ben a raise a song mysel' once," and then described to Colonel Higginson that on one occasion when a slave he began to sing, "O, de old nigger-driver."

THE "SHOUT" RELIGIOUS DANCES

Then another said, "Fust ting my mammy tole me was, notin' so bad as niggerdrivers." This was the refrain, and in a short time all the slaves in the field had made a song which was grafted into their unwritten literature. Another negro, in telling Mr. J. Miller McKim, one of the teachers on the island, how they made the songs, said, "Dey work it in, work it in, you know, till dey get it right, and das de way."

The "shout," one of the most peculiar and interesting of the religious customs of the slaves, still kept up to some extent among the negroes on the coast, is discountenanced by many of the colored preachers now-a-days. It is what may be called a prayer-meeting, interspersed with spasmodic enthusiasm. The population of a plantation gathers together in some cabin at evening, and, after vociferous prayer by some of the brethren, and the singing of hymns in melancholy cadence by the whole congregation, all the seats are cleared away, and the congregation begins the genuine "walk-around" to the music of the "spiritual."

The following description of the dance, which is a main feature of these shouts, appeared in the New York Nation, in 1867:

"The foot is hardly taken from the floor, and the progression is mainly due to a jerking, pitching motion, which agitates the entire shouters, and soon brings out streams of perspiration. Sometimes they dance slowly; sometimes, as they shuffle, they sing the chorus of the spiritual, and sometimes the song itself is also sung; but more frequently a band composed of some of the best singers and of tired shouters stands at the side of the room to " base " the others singing the body of the song, and clapping their hands together or on their knees. Singing and dance are alike extremely energetic, and often when the shout lasts into the middle of the night, the monotonous thud of the feet prevents sleep within half a mile of the 'Praise-House.'"

SONGS OF SOUTH CAROLINA NEGROES

I append three or four of the most beautiful of the songs sung by the negroes of the lowland coast of South Carolina. That entitled "Lord Remember Me " attracted universal attention when it first appeared, shortly after the war, at the North. It was set to weird music, and had the genuine ballad flavor:

I HEAR FROM HEAVEN TO-DAY

Hurry on, my weary soul,

And I yearde from heaven to-day,

My sin is forgiven, and my soul set free,

And I yearde, etc.

A baby born in Bethlehem,

De trumpet sound in de oder bright land;

My name is called and I must go,

De bell is a-ringin' in de oder bright world.

--------------------------------

LORD REMEMBER ME

Oh Deat' he is a little man,

And he goes from do' to do';

He kill some souls and he wounded some,

And he lef some souls to pray.

Oh, Lord, remember me,

Do, Lord, remember me;

Remember me as de year roll round,

Lord, remember me.

------------------------------

NOT WEARY YET

O me not weary yet, (repeat)

I have a witness in my heart;

O me no weary yet, Brudder Tony,

Since I ben in de field to fight.

O me, etc.

I have a heaven to maintain,

De bond of faith are on my soul;

Ole Satan toss a ball at me,

Him tink de ball would hit my soul;

De ball for hell and I for heaven.

---------------------------

HUNTING FOR THE LORD

Hunt till you find him,

Hallelujah!

And a-huntin' for de Lord,

Till you find him,

Hallelujah!

And a-huntin' for de Lord.

-------------------------------------

I SAW THE BEAM IN MY SISTER'S EYE

I saw de beam in my sister's eye,

Can't saw de beam in mine;

You'd better lef your sister's door,

Go keep your own door clean.

And I had a mighty battle, like-a Jacob and de angel,

Jacob, time of old;

I did n't 'tend to lef 'em go,

Till Jesus bless my soul.

---------------------------------

RELIGION SO SWEET

O walk Jordan long road,

And religion so sweet;

O religion is good for anything,

And religion so sweet.

Religion make you happy,

Religion gib me patience;

0 'member, get religion.

I long time ben a huntin',

I seekin' for my fortune;

O I gwine to meet my Savior,

Gwine to tell him bout my trials.

Dey call me boastin' member,

Dey call me turnback Christian;

Dey call me 'struction maker,

But I don't care what dey call me.

Lord, trial 'longs to a Christian,

0 tell me 'bout religion;

I weep for Mary and Marta,

I seek my Lord and I find him.

------------------------------------

MICHAEL, ROW THE BOAT ASHORE

Michael, row de boat ashore,

Hallelujah!

Michael boat a gospel boat,

Hallelujah!

I wonder where my mudder deh,

See my mudder on de rock gwine home,

On de rock gwine home in Jesus' name;

Michael boat a music boat,

Gabriel blow de trumpet horn,

0 you mind your boastin' talk;

Boastin' talk will sink your soul.

Brudder, lend a helpin' hand;

Sister, help for trim dat boat.

Jordan's stream is wide and deep;

Jesus stand on t' oder side.

1 wonder if my massa deh;

My fader gone to unknown land,

O de Lord he plant his garden deh.

-----------------------------------

I WISH I BEN DERE

My mudder, you follow Jesus,

My sister, you follow Jesus,

My brudder, you follow Jesus,

To fight until I die.

I wish I ben dere,

To climb Jacob's ladder;

I wish I ben dere,

To wear de starry crown.

------------------------------------

JESUS ON THE WATER-SIDE

Heaven bell a-ring, I know de road,

Heaven bell a-ring, I know de road;

Jesus sittin' on de water-side,

Do come along, do let us go,

Jesus sittin' on de water-side.