Jimmie Rodgers Biography-1927

In 1927 Charles Lindbergh became the first individual to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean; Babe Ruth hit sixty home runs in a single season; "The Jazz Singer" ushering in the first motion picture with a sound track; and “The Father of Country Music” made his first recording.

Jimmie Rodgers, known as the Singing Brakeman and also as America’s Blue Yodeler, was the first performer inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. His brass plaque in the Country Music Hall of Fame reads, "Jimmie Rodgers name stands foremost in the country music field as the man who started it all." With this statement Country Music has ignored the real founders like Fiddlin’ John Carson, yodeler Riley Puckett and Vernon Dalhart, whose record sales Rodgers could never match. Jimmie was someone that the average Country fan could understand, but more than that he was Country Music’s first real star. These are the words inscribed on his statue in his hometown of Meridian, Mississippi:

"His is the music of America. He sang the songs of the people he loved, of a young nation growing strong. His was an America of glistening rails, thundering boxcars, and rain-swept night, of lonesome prairies, great mountains and a high blue sky. He sang of the bayous and the cornfields, the wheated plains, of the little towns, the cities, and of the winding rivers of America."

Rodgers music embraced many different styles: traditional melodies and folk music of his southern upbringing, early jazz, stage show yodeling, Hawaiian music, the work chants of railroad section crews and, most importantly, African-American blues. As the first Country Music star Rodgers was immensely popular in his own time, and a major influence on generations of country artists. Johnny Bond, Crystal Gayle and Lynyrd Skynyrd have recorded his songs. Gene Autry, Ernest Tubb, Jimmie Davis, Hank Snow, Lefty Frizzell, Bill Monroe, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Tanya Tucker, Steve Earl and Dolly Parton are only a few of the dozens of stars who have acknowledged the impact of Jimmie Rodgers’s music on their careers.

Nolan Porterfield, who helped me with some details in my biography, said this about Jimmie: "Folks everywhere knew about Jimmie Rodgers, and although some of them were reluctant at first to believe that he was really there in person, playing their own town, they soon learned that he was as much at home in Sweetwater or O'Donnell as in front of a Victor microphone or on the stage of some fancy big-city theater. Vernon Dalhart and Gene Austin might make a lot of records, but they didn't come out into the boondocks to rub shoulders and tell bawdy jokes and laugh with the plain folks who bought them. The effects of the Blue Yodeler's tours had been apparent for some time. Just when the first baby was named after Jimmie Rodgers isn't known, but there would be many to follow; and everyone had a personal story to tell about him what Jimmie had said the time he played Wetumpka or Conroe, how he'd given his guitar to a blind newsboy in McAlester, the way he sang his way out of jail after killing his girlfriend, the time he invented the yodel, ran off with the mayor's wife, threw beer bottles off the hotel balcony, shot up the city square, or paid off the mortgage for a destitute widow. Most of the stories were pure fabrication, a few had some basis in fact, but all were derived from the simple, eloquent circumstance that Jimmie Rodgers was a genuine hero to those who needed one most-the plain, ordinary people across the land."

First Recording Sessions- Bristol Sessions

Rodgers and the Carter Family were both discovered at the Bristol recording sessions called the “big bang” of Country Music in August 1927. On Aug. 4 Rodgers recorded two songs for Ralph Peer, Victor’s A &R man at a temporary recording studio in Bristol, a city on the Tennessee and Virginia border. From the accounts by Peer, Country Music historian Charles Wolfe, biographer Nolan Porterfield and other sources we can see that Rodger’s burning desire to succeed and just plain luck helped him on the road to fame. “The best things in life seem to occur by pure accident,” said Peer. “We strive to accomplish something worthwhile; success finally comes to us, but usually from an unexpected source.” Aug. 4 was Rodgers unexpected source.

By March 1927 Rodgers had moved to the mountains in Asheville, North Carolina and wrangled a regular unpaid spot on local radio station WWNC. With typical charm he had persuaded the Tenneva Ramblers (brothers Claude and Jack Grant, with Jack Pierce on fiddle), a string band from Bristol, to join him in on the radio in May. Rodgers played banjo and guitar for the new group he named: The Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers. When the radio program was abruptly canceled in June, they began booking engagements, eventually finding regular work at a plush resort in the Blue Ridge Mountain town of Marion.

Rodgers was planning to go north to Washington, DC before going to NYC to audition in person with record companies. Rodgers need better transportation so he and Jack Pierce went back to Bristol to get a newer car. Pierce’s father loaned Jimmie $300 for a two-year old Dodge until Carrie’s sister could wire the money from Washington, DC. That night they found out that Ralph Peer, an agent for the Victor Talking Machine Company, was making recordings in Bristol and the next morning arranged an audition for the band with Peer for Aug. 3. Rodgers and Pierce drove back to Marion, gave notice to the resort that they were leaving and after picking up Carrie and Anita in Asheville, the whole group headed back to Bristol to audition. They dropped Anita and Carrie Rodgers at the boarding house run by Jack Pierce's mother located just across State Street from the temporary recording studio Peer had set up, tuned up their instruments and headed to the studio.

Peer was done recording and auditioned The Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers as soon as they arrived. Not happy with their repertoire of current dance tunes (Peer wanted new hillbilly songs he could copyright) or Rodgers he nevertheless scheduled them to record the next day. Peer was impressed with the Tenneva Ramblers and thought that Rodgers fronting the band was a mismatch. “The records wouldn’t have been any good if Jimmie had sung with this group (Tenneva Ramblers),” said Peer. “He was singing blues and they were doing old-time fiddle music. Oil and water don’t mix.”

According to Charles Wolfe, Peer gave an interview in 1928 in which he recalled that Jimmie Rodgers had been “running around in the mountains before his session in Bristol, and that when he tried out he was laughed at.” After the audition The Tenneva Ramblers decided they didn’t want record the next day as “The Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers.” After all, they had only played with Rodgers a few months, had no great loyalty to him (they formed four years earlier in 1923) and he was planning to leave for Washington, DC.

That night the group met at the boarding house to rehearse. Claude Grant said, “At some point Jimmie brought up the question of how we would record; would it be “Jimmie Rodgers and the Entertainers or what?” An argument between Jimmie and Jack Grant ensued and the band broke up. Jimmie announced, “All right, I’ll just sing one myself,” and immediately went to Peer and arranged a solo for the next day.

“I did feel sorry for Jimmie on the first go-round,” explained Peer. The Ramblers quickly recruited a banjo player and recorded by themselves. Their classic “The Longest Train I Ever Saw,” a version of the well known "In the Pines," was one result-- it was to be the start of a long recording career for the band members.

Jimmie showed up the next day at 2:00pm on Aug 4th wearing a faded old suit and carrying his old Martin guitar. Peer was disappointed to find that most of the songs Rodgers had been singing were fairly new pop songs and asked him for ones that sounded old but could be copyrighted. “We ran into a snag almost immediately because, in order to earn a living in Asheville, he was singing mostly songs originated by New York publishers—the current hits,” said Peer. “Actually, he had only one song of his own, "Soldier's Sweetheart," written several years before. When I told Jimmie what I needed to put him over as a recording artist, his perennial optimism bubbled over. If I would give him a week he could have a dozen songs ready for recording. I let him record his own song, and as a coupling his unique version of "Rock All Our Babies to Sleep." This, I thought, would be a very good coupling, as "Soldier's Sweetheart" was a straight ballad and the other side gave him a chance to display his ability as a yodeler.”

"I thought his yodel alone might spell success," Peer recalled years later that showing he had already put a positive spin on the session, after all Rodgers became one of his top artists and made him a lot of money. “He was quite ill at the time, and decided that instead of trying to return to Asheville he would visit a relative in Washington, D.C. The money was enough to pay for this trip.”

Second Session

Jimmie put his daughter and Aunt Lottie May on a train to Alabama and he and Carrie drove his newly purchased Dodge to Washington DC where they stayed temporarily at a Carrie’s sister’s house. Carrie found work as a waitress and Rodgers played whenever he could. His first single was released in October 7, 1927 was selling modestly. A month later was anxiously waiting to find out the exact sales status of the first recordings, and to arrange another session with Peer. They used their entire savings, “a whole ten dollars” for Rodgers to travel to NYC to visit Peer in the Victor offices. In November Rodgers went to NY, managed to charge a fancy hotel on credit to Victor Records and called Peer: “I just happened to be in town and decided to see if you needed any more recordings.” Peer agreed to record him again, and the two met in Philadelphia before traveling to Camden, New Jersey, to the Victor studios.

“Actually we did not have enough material to record,” said Peer, “and I decided to use one of his blues songs to fill in.” That blues song, “T for Texas” also known as “Blue Yodel Number 1,” was Rodger’s first hit song and would catapult him to fame.

At the second session on Nov. 30 recorded "Ben Dewberry's Final Run"; "Mother Was A Lady"; "Away Out on the Mountain"; and "T for Texas" in Victor’s Camden, NJ studios. Rodgers and Peer had issued "Mother Was A Lady" as a Jimmie Rodgers composition “If Brother Jack Were Here.” [When the single was released eight months later a lawsuit was threatened by the composers. Victor stopped selling the initial pressing and it was released under the titile "Mother Was A Lady." Many of Rodgers’ songs were arranged from traditional sources; an example is his “In the Jailhouse Now” and many of his blue yodels.] The single “T for Texas/Away Out on The Mountain” released in Feb. 1928 sold slowly at first.

After receiving his first royalty check for a meager $27 early in 1928, Rodgers was not happy with Peer or Victor and approached Columbia for an audition in Atlanta. Frank Walker, head of Columbia’s Old Familiar Tunes that had recorded the Skillet Lickers and would one day sign Hank Williams, listened to Jimmie sing. He turned to his assistant Bill Brown and said, “Who needs Jimmie Rodgers, we’ve got Riley Puckett.”

Roger’s went back in the studio at Camden, New Jersey on Feb. 14 and 15 with two members of the Blue and Gray Troupadors, Ellsworth Cozzen and Julian Ninde. The songs recorded included “In the Jailhouse Now,” “Brakeman’s Blues,” and two more blue yodels: “Blue Yodel No. 2 (My Lovin’ Gal, Lucille)”, and “Blue Yodel No. 3 (Evening Sun Yodel).”

In April Rodgers received his second check for $400 from Victor reflection over 100,000 in sales. Then by the summer of 1928 “T for Texas” really took off giving Rodgers his first hit single. He was averaging $1,000 a month in royalties. The singles he recorded in 1928 would reportedly all sell over a million copies. Jimmie Rodgers was a star.

Early Life

Born James Charles Rodgers on September 8, 1897, in the east Mississippi town Pine Springs near Meridian, Jimmie was the youngest of three boys of Eliza and Aaron Rodgers. Aaron was a section foreman on the Mobile and Chic Railroad and his work kept him away from home much of the time. Eliza was a frail woman for much of her life, and died during childbirth when Jimmie was five years old.

After their mother died, Jimmie’s oldest brother Walter, who was seventeen, worked with their father on the railroad while Jimmie and Tal went to live with relatives first in Scooba, Mississippi then in nearby Geiger, Alabama. In October 1904 Jimmie’s father Aaron remarried, moved the family to Lowndes County and began an ill-fated attempt to become a farmer. Soon Aaron returned to work as section foreman on the New Orleans and Northern Railroad and Jimmie and Tal were sent to Pine Springs to live with their Aunt Dora Bozeman because their stepmother and new baby traveled with their father.

From 1906 when Jimmie was nine to 1911 he lived with Dora, a former teacher who held degrees in music and English. She exposed him to a number of different styles of music, including vaudeville, pop and dance hall. It was during this time that he had the most stability in his early life, he went to school, picked cotton and started picking guitar. According to Rodgers in an interview, “I played guitar at night after picking cotton when I was a kid.” During this time Rodger’s learned guitar and banjo. He also added mandolin at a later time.

Jimmie’s affinity for entertaining came at an early age, and the lure of the road was irresistible to him. Attracted to music and wanting to be a performer, he organized his first homemade tent show from his sister-in-laws bedsheets at age eleven. Brought back home by his father several towns away, he had managed to make enough money to pay for the materials for his “tent.” For the second venture with his troupe, he had charged to his father, without his knowing, an expensive sidewall canvas tent. Again he was brought back home.

When he was twelve Jimmie won an amateur contest sponsored by Meridian’s Elite Theater where he sang “Bill Bailey” and “Steamboat Bill,” accompanying himself on the banjo. This taste of fame helped him get an unpaid spot performing with a medicine show that was passing through town. When the medicine show left so did Jimmie and his family did little to stop him. “Making a little money and having a good time too,” wrote Rodgers to his Uncle Tom Bozeman, who ran a barbershop where Rodgers hung out.

Young Jimmie quit the show in Birmingham because, “The show man wouldn’t treat me right.” Undaunted about being stranded 100 miles from home, Jimmie got a job working for a Mr. Tuggles for 50 cents a day and board. Jimmie wrote aunt Dora that he ‘Had many friends and a sweet girl too.” At the show he learned black-face comedy, and various singing styles and songs to add to his banjo, mandolin, and guitar repertoire. After a few months Aaron Rodgers retrieved his son and told him, “You got to go to school or work on the railroad,” so Rodgers opted to work on the railroad.

Jimmie was 13 when his father found him his first job working on the railroad as waterboy on his father's gang. In her 1935 biography of her late husband, Carrie Rodgers presents Jimmie Rodgers as a crucible in which the “African-American” songs he learned as a waterboy were forged within his “Irish soul” into something distinctive and new. Of the early influence of the African-American railroad laborers with whom Jimmie had extensive contact as a waterboy, she writes: The grinning, hard-working blacks who took Aaron Rodgers’s orders made his small son laugh—often. Though small he was white. So, even when they bade him “bring that water ‘round” they were deferential. During the noon dinner-rests, they taught him to plunk melody from banjo and guitar. They taught him their songs: moaning chants and crooning lullabies.

Singing Brakeman

Jimmie became a flagman then baggage-master. Then in 1914 he got a job as brakeman on New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad. He wrote to his aunt Dora, “I am making a man of myself.”

Whatever his musical ambitions might have been at that time, he kept coming back to Meridian and to railroading, like his father and older brother. Jimmie enjoyed hopping on board, pulling the whistle, and entertaining the work crews with songs on his guitar. More important, as he traveled the miles and spent long hours "waiting for a train," he learned how, the yardmen, switchers, and hoboes amused and impressed themselves with gandy dancing, lullabies, and the blues. Mississippi in the 1920s was a haven for black blues artists. Jimmie Rodgers had extensive contact with these musicians and singers through his work and travel on the railroad. The simplicity, directness, and depth of feeling inherent in the blues also became essential elements in Rodgers' music, and his interpretation of the black blues was instrumental in his success.

Rodgers Marriages

In January 1917 Jimmie was a guest at the home of Tom Conn, a fireman on the Illinois Central who lived in Durant, Mississippi. Rodgers was looking for a permanent job there since he had no regular train assignment at this time on the railroad. There he met Conn’s cousin, Stella Kelly. On May 1, after a short courtship, they were married; Jimmie and his new bride were only nineteen. The newlywed got an apartment near the rails in Durant and Jimmie began working as an apprentice mechanic. The job didn’t work out and they moved to Louisville, Stella’s hometown. Jimmie got a part-time job as a railroad brakeman and returned to his nomadic ways; playing music, drinking and spending what little money he made on a good time with his friends. Later Stella would comment on Jimmie’s music, “I didn’t think it would ever amount to anything. I didn’t think he was very good.”

“He was kind,” said Stella. “He was just as sweet as he could be, but he was the poorest businessman I ever saw.”

After six months of asking her father for money to pay the rent, her parents stepped in and Stella, two months pregnant, moved back home with them. When Jimmie landed a job as a baggage man and brakeman on the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad for thirty dollar a week The Kelly’s moved to Oklahoma, not letting Rodgers know of their location. After their daughter Kathryn was born Feb. 16, 1918, the Kelly’s didn’t want to have anything to do with Rodgers. Jimmie claimed he never knew he had a daughter until many years later.

In the summer of 1919, he met sixteen year old Carrie Williamson, a preacher's daughter. After he became officially divorced, the New Orleans & Northeastern Railroad laid off Jimmie, and he began performing various bluecollar jobs, looking for opportunities to sing. He then married Carrie on April 7, 1920 without her parent’s permission while she was still in high school. The Williamsons, making the best of the situation, accepted Jimmie into the fold. Times were hard for the Rodgers for the next several years, railroad wages dropped and there were frequent layoffs, the only bright spot was their first child Carrie Anita born Jan. 30, 1921.

Billy Terrell’s Comedians

In November of 1923 Rodgers auditioned for Billy Terrell’s Comedians, a traveling tent show, that was performing in Meridian. Jimmie’s first performance was at the next stop in Hattieburg. It was during this time that became being known as a “blue yodeler.” According to Terrell: “The big tent was packed that night and I gave him a real build-up. Out came Jimmie with that big smile on his face. He walked to the center of the stage and started whipping that guitar- then he pulled his train whistle and had them in his hand.”

Rodger’s tour came to an aburpt halt when the second of their two daughters died of diphtheria six months after her birth in December. By that time, Rodgers had made it to New Orleans with Terrell’s troupe, and returned home in a boxcar- broke with no money for the funeral. Carrie’s family helped out and after the funeral Rodger’s found work on a railroad which traveled west through Texas, New Mexico Arizona and Colorado. When he returned to Meridian he had a bad cold and hacking cough.

Tuberculosis

He went back working on the rail that summer but his cough just got worse. In 1924, at the age of 27, Jimmie started coughing up specks of blood and while visiting his father in Geiger, Alabama, suffered a hemorrhage. The local doctor diagnosed tuberculosis, a disease for which there was no cure and from which many people died. Rodgers entered the TB ward near Meridian and soon felt better. He discharged himself from the hospital to form a trio with fiddler Slim Rozell and his sister-in-law Elsie McWilliams. They played a few dances in the Meridian area. He also played with a tent show in 1925 featuring Hawaiian music “Hawaiian Show and Carnival” two guitar and steel guitar. When Rodgers wasn’t working the rails he did blackface comedy with medicine shows while he sang.

After a stint in Florida from fall of 1925 until Feb 1926, he moved his family out to Tucson, Arizona, believing the change in location would improve his health. He was employed as a switchman by the Southern Pacific. In Tucson, he continued to sing at local clubs and events. Rodgers was sick and started missing work. Then after he played at a dance and missed work, the yard superintendent fired him. The job lasted less than a year, and the Rodgers family (wife Carrie and daughter Anita) had settled back in Meridian by late 1926.

Asheville, NC- The Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers- Tenneva Ramblers 1926

In early 1927 Rodgers moved to Asheville, NC in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Albert Fullam had urged Jimmie to go there for his health and Fillam had relatives there that would help him until he found work. Jimmie began working as a janitor and a cab driver, as well as doing odd-jobs for the Chief of Detectives, Fred Jones. Soon Rodgers earned enough money to bring Carrie and Anita to Asheville to but music was always on his mind. “I managed to make a living entertaining, playing for dances and giving programs,” he said in a later interview, “but it was hard sledding.”

In February of 1927, Asheville's first radio station, WWNC, went on the air, and on April 18, at 9:30 p.m., Jimmie and Otis Kuykendall performed for the first time on the station. Rodgers went to Johnson City soon after he learned of the upcoming 52nd District Rotary Clubs’ annual convention being held on April 24-26, hoping to find an opportunity to perform on several entertainment programs being offered to the attendees during the three-day event.

In addition to Rodgers, numerous other talents arrived from across the area, including a popular group from Bristol, the Tenneva Ramblers, choosing their abbreviated name from the fact that the city’s main street is divided between Tennessee and Virginia. The spirited group consisted of Claude Grant (lead vocals, guitar), Jack Grant (mandolin), and Jack Pierce (fiddle). Greatly impressed with this band, Jimmie invited them to return with him to Asheville to broadcast over WWNC, giving the impression that he was rapidly becoming a celebrity. Although the Ramblers were interested they decline Jimmie’s offer because they were already booked for the next few weeks. Sensing the trio might later reconsider his offer, Rodgers gave them his phone number to contact him after he returned to North Carolina.

In May, after the Tenneva Ramblers finished their planned engagements, they contacted Jimmie who told them the radio offer was still available. They headed toward Asheville in a worn-out jalopy, riding on slick tires and traveling over unpaved mountainous roads so steep, winding, and treacherous, they were almost impassable. On May 30 they debuted on the radio with a new name: the Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers, establishing Rodgers as the leader of the group. The performances provoked two separate comments that hinted at Rodgers' future success. A review in The Asheville Times remarked that "Jimmy (sic) Rodgers and his entertainers managed...with a type of music quite different than [the station's usual material], but a kind that finds a cordial reception from a large audience." And from another columnist: "whoever that fellow is, he either is a winner or he is going to be."

Their radio stint would prove to be a brief one ending June 13; the station bosses did not like the music they were playing and singing. The Rodgers Entertainers began working anywhere they could find appearances. “I’ll never forget the time Jimmie booked us at Hendersonville,” Claude Grant remembered. “He quickly got some handbills printed out and we spent most of the day around the drugstore singing and playing. But when we went out there that night only the janitor showed up.”

In June 1927, the group made a second visit to Johnson City, this time attracted by news of an upcoming Trade Exposition and Tri-State Fair (now called the Appalachian District Fair). Upon arriving Rodgers booked the group a spot during the festivities. On July 2 a storm destroyed part of the bandstand and the band performances were delayed several days. The crowd dissipated and most of the bands barely broke even.

The next day Rogers booked a theater in Marion, near Asheville. That led to a continuing engagement at the plush North Fork Mountain Resort, with free rooms and rather substantial salary. The Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers were popular with the guests and had a place to play for the summer season. Rodgers had been trying to get recorded, first he wrote Victor and then Brunswick. Both had turned him down. He was planning on heading north towards NY studios to audition in person. Since his sister-in-law lived in Washington, DC he was planning relocate in the Nations Capitol. Pierce and Rodgers went back to Bristol to see if Pierce’s father would buy a newer car to make the trip. It was then that they found out that Ralph Peer was in town and managed to meet him. “Bring the whole bunch in,” Peer told them. “I’ll listen to you. No promises- we’ll see.” [For the complete details about The Bristol Sessions in August, 1927 see: First Recording Sessions- Bristol Sessions at the beginning of this biography]

Blue Yodels

Rodgers became known as “The Blue Yodeler” and because of his great popularity influenced many Country singers. Curiously, he even influenced African singers: Such was the magnetic power of Jimmie Rodgers' late 1920s commercial recordings. What made them so irresistible was Jimmie's 'blue yodel'. Within months of their release in the States, Jimmie's records were available in South Africa, and by 1932 a black South African singer named William Mseleku had 'recorded some songs directly modeled on Rodgers's 'Blue Yodel' series'.

Rodgers’ recording and performing successes in the late 1920s and early 1930s ensured that yodeling “became not only an obligatory stylistic flourish, but a commercial necessity.” By the 1930s yodeling was a widespread phenomenon and had become almost synonymous with country music. By the 40s yodeling was largely a thing of the past; identified with the 20s and the string band era. The new honky-tonk style used an occasional yodel flourish within the context of the song but the extended yodel breaks and fills were gone.

The Blue Yodel songs are a series of thirteen songs written and recorded by Jimmie Rodgers during the period from 1927 to his death in May 1933. The songs were based on the 12-bar blues format and featured Rodgers’ trademark yodel refrains. Rogers was the first Country singer to add a yodel as a tag (ending) to a standard 12 bar blues and other songs.

Ralph Peer, who was impressed by Rodgers yodel remembered in a 1953 interview: “We worked hard far into the night getting enough material in shape for the first recording session. Actually, we did not have enough material, and I decided to use some of his blues songs to "fill in." When we recorded the first blues I had to supply a title, and the name "Blue Yodel" came out. The other blue yodels made at the same time had titles suggested by the words, but when I witnessed the tremendous demand for the original, I decided to change these names to "Blue Yodel No. 2," "Blue Yodel No. 3," etc.”

Regardless of Peer’s assertion that he named “T for Texas” the first “Blue Yodel,” he didn’t give Jimmie his nickname. Billy Terrell already referred to Rodgers as a “Blue Yodeler” as early as 1923. Another reference [It was in Johnson City Tennessee in April 1926 that a man seeing Jimmie Rodgers in a return engagement said to his girlfriend that blue yodeler’s come back to town again] shows that Rodgers was already known by that nickname.

Rodgers didn’t create blue or blue yodeling he only made it popular. African-American yodelers had already adapted Swiss Alpine yodeling in American song. The American yodel gained momentum in 1840 with minstrel troupe quartets based on the success of the Tyrolese Rainer Family. Touring the Eastern states from 1839 to 1843, the Rainers performed simple, mixed-voice arrangements of Tyrolese folksongs, with yodeling. America's most popular nineteenth-century singing family, the Hutchinsons, made regular use of yodeling. Quick to parody the singing-family idea, minstrel show quartets took up yodeling as “tyrolesian business.” An 1853 program for Christy's Minstrels announces their burlesque of the Hutchinson Family singing “We Come from the Hills with Tyrolean Echo.”

In 1905 Beulah Henderson (Washington) was the first vaudevillian known to offer a combination of yodel songs and blues/ragtime songs. Her advertisements in the Freeman claimed she was 'America's Only Colored Lady Yodeler'. In 1908 Monroe Tabor yodeled with the Dandy Dixies: “Mr. Tabor is a new tenor with a good voice, which suffers only from a lack of training. While there was not quite enough comedy and ragtime, the Yodel song, “Sleep, Baby, Sleep,” was greatly in atonement and showed Monroe Tabor to be unexcelled as a yodeler.” Rodgers first record featured the same yodel song “Sleep, Baby, Sleep.”

In 1923 “Sleep, Baby, Sleep,” was recorded by an African-American yodeler named Charles Anderson. Not mentioned, however, is the fact that Anderson's total record output - eight sides from 1923 and 1924 - is a near even mixture of yodels and blues songs. The Indianapolis Freeman, a nationally distributed weekly newspaper that catered to black entertainers, said that Charles Anderson was one of several black yodelers who performed extensively in front of black and white audiences during the first two decades of this century.

“Yodeling Blues” was copyrighted by the Clarence Williams Music Publishing Company on March 31, 1923, and commercially recorded twice that same year. Sara Martin and Eva Taylor (Clarence's wife) recorded it on May 4, 1923 (Okeh 8067). The label credits “Piano Accomp. by Clarence Williams” and “Yodel Cornet Obligate by Thomas Morris.” Between twelve-bar blues verses about losing a man, the singers warble a distinct, "yodel-odel-odel, de-yodel-odel-odel". On June 14, 1923, Bessie Smith recorded a darker version of Yodeling Blues (ColumbiaA3939). On both of these recordings the yodeling is more implied than realized. The yodel is expressed as an echo and comment on the blues:

I'm gonna yodel my blues away, I said, my blues away,

I'm gonna yodel, yodel my blues away, yeee-hoo,

I'm gonna yodel 'til things come back my way.

There were also white yodelers that recorded before Rodgers. Riley Puckett, Columbia Records yodeling star had already recorded the same yodel song, “Sleep Baby Sleep” in 1924. Emmett Miller, a blackface yodeler, who recorded “Lovesick Blues” in 1925, surely could have been an influence. To what extent Jimmie Rodgers was aware of the African-Amercian blues recording or the earlier Country recordings is not known.

Carrie Rodgers, Jimmie's second wife and first biographer, said he was “fascinated by shows and show people. Jimmie haunted the show lots and stage entrances of theaters ... As long as he could possibly scare up a dollar that wasn't busy he would spend it for shows - any kind - (and) for phonograph records. He bought phonograph records by the ton, and toward the betterment of his own brand of music-making, he would play those records over and over.”

Jimmie Rodgers Blue Yodel Song Details

"Blue Yodel” [aka “Blue Yodel No. 1 (T for Texas)”], recorded on November 30, 1927 at Camden, New Jersey; released on February 3, 1928 (BVE 40753-2).

“Blue Yodel No. 2 (My Lovin’ Gal, Lucille)”, recorded on February 15, 1928 at Camden, New Jersey; released on May 4, 1928 (BVE 41741-2).

“Blue Yodel No. 3 (Evening Sun Yodel)”, recorded on February 15, 1928 at Camden, New Jersey; released on September 7, 1928 (BVE 41743-2).

“Blue Yodel No. 4 (California Blues)”, recorded on October 20, 1928 at Atlanta, Georgia; released on February 8, 1929 (BVE 47216-4).

“Blue Yodel No. 5 (It’s Raining Here)”, recorded on February 23, 1929 at New York, New York; released on September 20, 1929 (BVE 49990-2).

“Blue Yodel No. 6 (She Left Me This Mornin’)”, recorded on October 22, 1929 at Dallas, Texas; released on February 21, 1930 (BVE 56453-3).

“Anniversary Blue Yodel (Blue Yodel No. 7)”, recorded on November 26, 1929 at Atlanta, Georgia; released on September 5, 1930 (BVE 56607-3) - Jimmie Rodgers and Elsie McWilliams (Rodgers' sister-in-law).

“Blue Yodel No.11 (I’ve Got a Gal)”, recorded on November 27, 1929 at Atlanta, Georgia; released on June 30, 1933 (BVE 56617-4), after Jimmie Rodgers had died.

“Blue Yodel No. 8 (Mule Skinner Blues)”, recorded on July 11, 1930 at Hollywood Recording Studios, Los Angeles, California; released on February 6, 1931 (PBVE 54863-3).

“Blue Yodel No. 9 (Standin’ On the Corner)”, recorded on July 16, 1930 at Hollywood Recording Studios, Los Angeles, California (with Louis Armstrong, cornet, and Lil Armstrong, piano); released on September 11, 1931 (PBVE 54867-3).

“Blue Yodel No. 10 (Ground Hog Rootin’ in My Backyard)”, recorded February 6, 1932, at Dallas, Texas; released on August 12, 1932 (BVE 70650-2).

“Blue Yodel No. 12 (Barefoot Blues)”, recorded on May 17, 1933 at New York, New York; released on June 27, 1933 (BS 76138-1), a month after Jimmie Rodgers’ death.

“Jimmie Rodger’s Last Blue Yodel (The Women Make a Fool Out of Me)”, recorded on May 18, 1933 at New York, New York; released on December 20, 1933 (BS 76160-1), seven months after Jimmie Rodgers had died.

Fame- Elsie McWilliams; 1928-1929

By 1928, Jimmie Rodgers had experienced a meteoric rise from obscurity to stardom similar in many ways to the later experiences of Hank Williams and Elvis Presley. By summer was making in excess of $1,000 a week in royalties. On top of this, according to Rodgers, he made “$1,500 a week” playing the Loew’s vaudeville circuit. He bought a fancy new Buick, new clothes and all the trappings of success.

His concerts continued to feature traditional songs like "Frankie and Johnny," sentimental favorites like "Mother Was a Lady," railroad songs, and his calling card Blue Yodels. Victor was releasing one of his records regularly every month and he was constantly looking for new material. One source was his sister-in-law, Elsie McWilliams, Rodgers former playing partner, who began sending him songs. Carrie's piano-playing sister composed and collaborated extensively with him during the critical early phases of his recording career. In May 1928 Mc Williams moved to Washington DC to write songs and help Jimmie learn her songs and polish some of his own ideas.

Rodgers did three sessions for Victor in 1928, five in 1929; and only one long session in June/July 1930 in Hollywood. In 1929 he did a tour with the Paul English Players. During the tour he got sick and one night couldn’t perform. Bill Bruner, a seventeen-year-old messenger boy for Western Union, who had learned every new Rodgers song as soon as it appeared on record, was in the audience with his girlfriend waiting to hear his idol.

Paul English announced that although there had been a slight delay, the show was about to begin. He asked if there was a fellow named Bill Bruner in the crowd. According to Porterfield: Heads turned in Bill's direction, and a low murmur rose. Spurred on by his girl's admiring gaze and the applause from friends around him, the surprised youngster managed to stand up shakily and identify himself. English promptly motioned him backstage. There the showman took his arm solicitously. "Some of my company tell me you sing and play like Jimmie Rodgers. Is that right?"

"Well I try awful hard."

"Do you have your guitar?"

"No, it's at home."

"Can you get it? We'll send you in cab. Jimmie is too sick to go on and we want you to take his place. Will you do it?"

Bill hesitated. "Don't you want to hear me first?"

"Happy Gowland has heard you. The comedian over there. He was in the restaurant today while you were playing. He says you sound just like Jimmie, and I'll take his word." Still in a daze, Bruner found a cab, went across town for his guitar, and returned as English was about to introduce the concert attraction.

"Many of you have been hearing Jimmie Rodgers here this week," he told the audience, "and you've also seen him around town, where he has been making personal appearances at the music stores. Unfortunately, being out so much in this damp weather, he has caught a bad cold ---" The crowd saw what was coming, and began to groan its disapproval. "However we have with us another Meridian boy who is also a fin entertainer. He sings and plays in Jimmie's style, and we think he deserves a chance to show you what he can do." Learning that Rodgers replacement was "another Meridian boy" helped to mollify the crowd, and English silenced the last dissenters by offering a full refund at the box office to anyone who still wanted his money back after hearing, 'Bill Bruner, the Yodeling Messenger Boy."

Bill did four or five numbers, ending as Jimmie characteristically did with a rollicking version of "Frankie and Johnny." The enthusiastic audience brought him back for six encores. A lengthy story in Billboard called it "a typical Horatio Alger incident in which the youthful hero steps in at the critical moment and saves the day." According to the trade journal's report, "The crowd went wild over the boy's efforts, and his imitation of Jimmie was so good that one could shut his eyes and imagine on of Jimmie's records being played. The young artist was a huge success, and when he returned to the dressing room, manager English found him not the least affected by his success.

Young Bruner took pride in the fact that no one asked for a refund; at the time that seemed as important as his ability to do an "almost perfect imitation" of Jimmie Rodgers. But his biggest thrill came the next evening, when English invited him back to the show as a guest and took him to Jimmie's dressing room in a small tent near the main canvas. Although many stars would have resented being upstaged by an unknown, Rodgers greeted the boy warmly, complimented him on his performance, and thanked him for helping out. "Jimmie gave me ten dollars," Brunner recounted, 'and I was tickled to death. Of course I though that was it, and I started to go." But Jimmie stopped him, went over to his instrument case, took out a guitar, and handed it to the boy. Recalling the incident later, Bruner's gentle Southern voice wavered slightly. "He said, 'Bill, this is a guitar I made some of my first records on, and I want you to have it.' Well, I just filled up - I didn't know what to say. Finally, I managed to thank him."

Rodgers Moves to Texas- 1929

For the last four years of his life, 1929-1933, Rodgers resided in Kerrville and then in San Antonio. The choice of the Lone Star State was natural- his first “Blue Yodel” was also known as “T for Texas.” In “Waiting for a Train,” recorded the next year, he recalled his hobo days and being unceremoniously tossed off a train in Texas, “a place I dearly love.” The Lone Star State creeps into other Rodgers’s tunes, including “The Land of My Boyhood Dreams,” “Anniversary Blue Yodel,” “Mother, Queen of My Heart,” and “Jimmie’s Texas Blues” with its hearty declaration: “Give me sweet Dallas, Texas, where the women think the world of me.” He also recorded three times in Dallas and once in the Alamo City.

A headline in the Friday, March 15, 1929, edition of the Abilene Daily Reporter announced: “Blue Yodel Singer Coming Here.” The article said, “A quest for health brought Rodgers out here, chiefly. He is going to buy a ranch and stay away from the stage and large cities for awhile.”

At first The Rodgers rented a private resident in Kerrville and by May were building their $50,000 dream-home named “Blue Yodeler’s Paradise.” Rodgers met Burt Ford who worked for Victor’s Dallas distributor, the T. E. Swann Music Company. Through the encouragement of the Swann Company or on their own initiative, the two men apparently decided to team up to promote the sale of Rodgers’s Victor records. As the West Texas representative for Victor, Ford lived in and worked out of Sweetwater, forty-three miles west of Abilene. The plan appears to have been for Rodgers to “headquarter” in Sweetwater using the town as base of operations to “fulfill West Texas vaudeville engagements.”

In the next few years, Rodgers was very busy. Jimmie headlined another tour in 1929 with R-K-O’s Interstate Circuit tour from May until late July across the south and southwest. He met the Burkes Brothers, Billy and Weldon who would perform and record with him the next few years.

I’ve watch Jimmie singing the three songs in his short film "The Singing Brakeman" for Columbia Victor Gems in the made in the fall of 1929 in Camden, NJ by Columbia Pictures. The fifteen-minute short features Rodgers singing “T for Texas,” “Waiting for a Train” and “Daddy and Home.” Film excerpts, which can be viewed on-line, is the only “live” video of Rodgers that exists today.

On another grueling tour that began on April 29, 1930 with Swain’s Hollywood Follies Rodgers once again became ill and even with Bill Bruner filling in for him dropped out on May 31. During this tour Stella, Rodger’s first wife, met him again at his performance in Oklahoma. It was then that she told him about their child whom most biographies say Rodgers was not aware existed. Stella was two months pregnant when she left Rodgers- it seems more likely that Rodgers ignored his past after losing all contact with her. Stella filed a lawsuit against Rodgers on Feb. 3, 1931 asking for child support and an additional monetary settlement. On June 9, 1932 their daughter Kathryn was awarded $50 per month child (equal to approximately $800 today) support until she reached her eighteenth birthday, a total sum of $2,650.

On July 16, 1930, Peer organized a session in Hollywood with a young jazz trumpeter named Louis Armstrong, whose wife, Lillian, played piano on the recording. Rodgers, who was notoriously difficult to play with because he had his own sense of rhythm, sang “Blue Yodel No. 9 (Standing On The Corner)” but never played with Satchmo again.

In January 1931 Jimmie teamed up with humorist Will Rogers as part of a Red Cross tour across the Midwest. Rogers called Jimmie his “long lost son” and began a friendship that would last the rest of Jimmie’s life [Later that year Jimmie would celebrate Will’s birthday with him on Nov. 4 in San Antonio]. Because of Jimmie increasingly poor health he dropped out of the grueling tour in February, only a month it started.

“I wouldn’t say Jimmie Rodgers was extremely clever,” said Peer in a 1958 interview, “but that he had a good intelligence from a hillbilly base. Above average (for a hillbilly). I looked after him. Of course looking after him was giving him all the money he asked for. And warning him when he got in too deep…I remember when he owed me a hundred thousand dollars at one time, so he must have made out okay. But I certainly never lost anything on Jimmie Rodgers.”

T.B. Blues- 1931

While T.B. was killing him and thousands of other Americans on January 31, 1931, at San Antonio, Texas, he recorded his version of “T.B. Blues” (Victor 23535). Although it was not the first version that was a hit for Victor [Victoria Spivey had a hit entitled “Dirty TB Blues in 1929], the song is one that Rodgers will always be identified with.

This is from Porterfield: As both an artistic achievement and a statement of his own mortality, "T.B. Blues" is perhaps the ultimate manifestation of Rodgers curiously dual attitude toward the disease that was killing him. For obvious reasons of taste and "image," the nature of his poor health was never named in news stories or publicity; but Jimmie himself made no effort to conceal it from those with whom he associated, nor was it a secret to most of his audiences, who, when he occasionally caught by a coughing spell on stage, were known to applaud sympathetically and shout, "Spit 'er up, Jimmie, and sing some more." Yet he rarely spoke to anyone about his health and appears to have simply ignored the whole matter as much as possible. This seeming ambivalence may explain why "T.B. Blues" is at once intensely authentic and yet calmly impersonal, as if the ominous disease and certain death are someone else's afflictions. How otherwise could he sing, so eloquently, so stoically, "I've been fighting like a lion, looks like I'm going to lose -- 'cause there ain't nobody ever whipped the T.B. Blues."

From beginning to end, from the singer's refusal to let his "good gal" make a fool of him by telling him he doesn't have T.B., to the final acknowledgement that "that old graveyard is a lonesome place" where "they put you on your back, throw mud in your face," "T.B. Blues" is both artistic achievement and the most eloquent evidence of Jimmie Rodger's tragic vision. It was a vision borne of his own courage and will, of his great zest for life and his own coming to terms with the transience of it, a vision substanial enough to elevate him to the ranks of poets and painters and artisans whose work illuminates and eases all our human lives.

When Jimmie Rodgers sang "T.B. Blues," his audiences knew that he meant it. It is what country music fans mean today when they bestow their highest accolade on an artist by calling them "sincere." The greatest evil lies in taking nothing seriously, a little sincerity goes a long way."

Jimmie and the Carter Family; Move to San Antonio 1931-32

Ralph Peer set up a recording session with Jimmie and the Carter Family in Louisville, Ky which began June 10, 1931 [For details see: The Carter Family biography]. It featured two skits (dialogue with music included) that Rodgers and Peer organized on short notice to capitalize on the success of the Skillet Lickers skits. June Carter Cash said, “They recorded with Jimmy Rodgers, and I remember once that mother (Maybelle) said Jimmy was too sick to play his guitar so she played it for him.” The first release “Jimmie Rodgers Visits the Carter Family” backed by Rodgers “Moonlight and Skies” by the two top Country recording artists for Victor was a big success by post 1929 standards. The other songs from that session (except Jimmie’s solo “Let Me Be Your Side Track”) were released five years later after Rodgers was dead and the Carters had spilt up.

By now the Great Depression’s effects began to severely cut into Rodger’s income which was largely based on his royalty checks from Victor. Even though he was one of the few recording stars popular enough to warrant recording during this period of time his record sales, which were averaging 500,000, slipped below 50,000. This figure would eventually slide in 1932 to around 15,000 and below, still much more than the average Country recording at that time. His health was deteriorating rapidly and he couldn’t depend on his performing to pull himself out.

Consequently Rodger’s sold his expensive Kerrville resort home, “The Blue Yodeler’s Paradise” in December 1931and moved to a duplex bungalow in San Antonio’s Alamo Heights. To avoid bankruptcy Rodgers still needed to performed occasionally (in Skeeter Kell and His Gang’s show for example) and make recordings. In 1932 Rodgers recorded with famous fiddler Clayton McMichen and his guitarist Slim Bryant in a series of session beginning August 10, 1932 and continuing for a week. Jimmie also recorded with Byrant on other sessions the following week. He also performed in short tours with the J. Doug Morgan Show in 1932 and again in Feb. 1933 before he was hospitalized.

Last Days

Despite his condition, he refused to stop performing, telling his wife that "I want to die with my shoes on." By early 1933, the family was running short on money, and he had to perform whenever he could -- including vaudeville shows and nickelodeons -- to make ends meet. For a while he performed on a radio show in San Antonio, but in February he collapsed and was sent to the hospital. Realizing that he was close to death, he convinced Peer to schedule a recording session in May. Rodgers, who received $250 per side up front, wanted to record a dozen sides to provide needed financial support for his family.

According to Peer, “What he wanted to do was come to New York and record about ten selections and get $2,500. I couldn’t see any objection.” Both Peer and Oberstein, Victor’s top recording engineers, were not available to be at the session so Fred Maisch ran the booth.

Rodgers was accompanied by his nurse, Mrs. Bedell, arrived in New York City on May 14. Peer met Rodgers and was concerned about his appearance telling him to get a few days rest before the session. On May 17 and 18 Rodgers recorded six sides with him singing and playing his guitar. At the end of the second day he was so weak had to be carried to a cab. Maisch telephoned Victor assistant Bob Gilmore and advised that further recordings be postponed. Rodgers phoned Gilmore from his hotel assuring him he could continue.

The next day Rodgers showed up and recorded two sides. He was still weak and had to be propped up with pillows on an easy chair. Gilmore refused to let him continue and told Rodgers to take two days off and get some rest. According to Porterfield: “Restless and impatient with his illness, Jimmie agreed only reluctantly. Gilmore suggested that he leave town for a day or two, and Rodgers decided a short trip into New England would do him good.” Jimmie and his nurse went to Cape Cod for two days; returning for the session on May 24.

“After a few days in Cape Cod, Jimmie returned to New York and called Peer's office to schedule the final four sides. However Peer was in Camden, where (among other matters) he was negotiating a new contract for Rodgers. Bob Gilmore made the arrangements in Peer's stead, scheduling studio time for the afternoon of Wednesday, May 24. He also suggested that they hire a musician or two to accompany Jimmie and spare him as much exertion as possible.” John Cali and Tony Colicchio were hired to back Jimmie who lasted for three straight hours before he could go no more. After resting on the cot in the rehearsal hall, they cut two takes of “Somewhere down below the Dixon Line” before Cali and Colicchio left for the day. Jimmie rested then cut “Years Ago,” the final song he would record in his lifetime.

The next day Rodgers, Alex Nelson and his nurse went to Coney Island where he rested on the beach. That evening after dinner Jimmie began to hemorrhage, coughing up blood. He seemed to get better but around midnight had a severe attack and the house doctor was called. Before he could arrive Jimmie slipped into a coma and simply drowned in his own blood. He died in the early hours of May 26, 1933- only 35 years old.

A train with a converted baggage car took his casket, covered in lilies, to Meridian. Hundreds of Country fans awaited the body's arrival in Meridian, and the train blew its whistle consistently throughout its journey. His body lay in state in the Scottish Rite Cathedral all day Monday 29 before it was taken to Oak Grove Cemetery and laid to rest beside his baby daughter, June.

Awards

When the Country Music Hall of Fame was established in 1961, Rodgers was one of the first three (with Fred Rose and Hank Williams) to be inducted. He was elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970 and, as an early influence, to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1997. "Blue Yodel No. 9" was selected as one of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll.

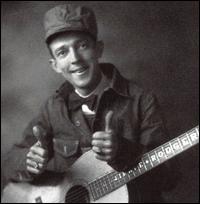

On May 24, 1978, the United States Postal Service issued a 13-cent commemorative stamp honoring Rodgers, the first in its long-running Performing Arts Series. The stamp was designed by Jim Sharpe (who did several others in this series), who depicted him with brakeman's outfit and guitar, giving his "two thumbs up", along with a locomotive in silhouette in the background.

Rodgers was ranked #33 on CMT's 40 Greatest Men In Country Music in 2003. Rodgers popularity soared in 1930s but by the start of World War II in 1942 Rodgers songs had almost disappeared from RCA Victor’s catalogue.

Nolan Porterfield: Hundreds of stories attest to what Jimmie Rodgers did with his voice, but the one that is most vivid to me is the short, simple one that Dick Furman in Kerrville told me about his father's death. Not long ago, more than forty years after he'd rambled the Texas Hill Country with Jimmie Rodgers, fishing and hoorawing and sipping drugstore bourbon, John Furman lay dying, alert but speechless, immobile, all but his right hand paralyzed from a massive stroke. By a system of squeezes with the good hand, he made it known that he wanted to hear music from the phonograph. Said Dick Furman, "Of course that meant Jimmie's records. I asked him, and he said yes. While the record played, he closed his eyes and died, squeezing my hand in time to the music."

Norm Cohen suggests the following as Rodgers' major contributions to country music:

a) Increased reliance on new compositions by contemporary writers and composers;

b) Increased reliance on studio musicians

c) Popularization of yodeling

d) Popularization of "white blues"-a hillbilly offshoot of the classic 12-bar blues popular with both white and black audiences in the mid- 1920s

e) Creation of a stable of lasting country music repertoire, still actively in use

f) Creation of a singing /guitar style emulated by many major artists during his lifetime and afterward

Jimmie Rodgers’ Complete Chronological Recordings

“The Soldier’s Sweetheart” (Victor 20864), recorded August 4, 1927, at Bristol, Tennessee.

“Ben Dewberry’s Final Run” (Victor 21245), recorded November 30, 1927, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Mother Was a Lady (If Brother Jack Were Here)” (Victor 21433), recorded November 30, 1927, at Camden, NJ.

“Blue Yodel” (Victor 21142), recorded November 30, 1927, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Away Out on the Mountain” (Victor 21142), recorded November 30, 1927, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Dear Old Sunny South by the Sea” (Victor 21574), recorded February 14, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Treasures Untold” (Victor 21433), recorded February 14, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“The Brakeman’s Blues” (Victor 21291), recorded February 14, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“The Sailor’s Plea” (Victor 40054), recorded February 14, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“In the Jailhouse Now” (Victor 21245), recorded February 15, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Blue Yodel No. 2 (My Lovin’ Gal, Lucille)” (Victor 21291), recorded February 15, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Memphis Yodel” (Victor 21636), recorded February 15, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Blue Yodel No. 3” (Victor 21531), recorded February 15, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“My Old Pal” (Victor 21757), recorded June 12, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“My Little Old Home Down in New Orleans” (Victor 21574), recorded June 12, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“You and My Old Guitar” (Victor 40072), recorded June 12, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Daddy and Home” (Victor 21757), recorded June 12, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“My Little Lady” (Victor 40072), recorded June 12, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Lullaby Yodel” (Victor 21636), recorded June 12, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Never No Mo’ Blues” (Victor 21531), recorded June 12, 1928, at Camden, New Jersey.

“My Carolina Sunshine Girl” (Victor 40096), recorded October 20, 1928, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“Blue Yodel No. 4 (California Blues)” (Victor 40014), recorded October 20, 1928, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“Waiting for a Train” (Victor 40014), recorded October 22, 1928, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“I’m Lonely and Blue” (Victor 40054), recorded October 22, 1928, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“Desert Blues” (Victor 40096), recorded February 21, 1929, at New York, New York.

“Any Old Time” (Victor 22488), recorded February 21, 1929, at New York, New York.

“Blue Yodel No. 5” (Victor 22072), recorded February 23, 1929, at New York, New York.

“High Powered Mama” (Victor 22523), recorded February 23, 1929, at New York, New York.

“I’m Sorry We Met” (Victor 22072), recorded February 23, 1929, at New York, New York.

“Everybody Does It in Hawaii” (Victor 22143), recorded August 8, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“Tuck Away My Lonesome Blues” (Victor 22220), recorded August 8, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“Train Whistle Blues” (Victor 22379), recorded August 8, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“Jimmie’s Texas Blues” (Victor 22379), recorded August 10, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“Frankie and Johnnie” (Victor 22143), recorded August 10, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“Whisper Your Mother’s Name” (Victor 22319), recorded October 22, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“The Land of My Boyhood Dreams” (Victor 22811), recorded October 22, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“Blue Yodel No. 6” (Victor 22271), recorded October 22, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“Yodelling Cowboy” (Victor 22271), recorded October 22, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“My Rough and Rowdy Ways” (Victor 22220), recorded October 22, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“I’ve Ranged, I’ve Roamed and I’ve Travelled” (Bluebird 5892), recorded October 22, 1929, at Dallas, Texas.

“Hobo Bill’s Last Ride” (Victor 22241), recorded November 13, 1929, at New Orleans, Louisiana.

“Mississippi River Blues” (Victor 23535), recorded November 25, 1929, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“Nobody Knows But Me” (Victor 23518), recorded November 25, 1929, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“Anniversary Blue Yodel (Blue Yodel No. 7)” (Victor 22488), recorded November 26, 1929, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“She Was Happy Till She Met You” (Victor 23681), recorded November 26, 1929, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“Blue Yodel No.11” (Victor 23796), recorded November 27, 1929, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“A Drunkard’s Child” (Victor 22319), recorded November 28, 1929, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“That’s Why I’m Blue” (Victor 22421), recorded November 28, 1929, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“Why Did You Give Me Your Love?” (Bluebird 5892), recorded November 28, 1929, at Atlanta, Georgia.

“My Blue-Eyed Jane” (Victor 23549), recorded June 30, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“Why Should I Be Lonely?” (Victor 23609), recorded June 30, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“Moonlight and Skies” (Victor 23574), recorded June 30, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“Pistol Packin’ Papa” (Victor 22554), recorded July 1, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“Take Me Back Again” (Bluebird 7600), recorded July 2, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“Those Gambler’s Blues” (Victor 22554), recorded July 5, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“I’m Lonesome Too” (Victor 23564), recorded July 7, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“The One Rose (That’s Left in My Heart)” (Bluebird 7280), recorded July 7, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“For the Sake of Days Gone By” (Victor 23651), recorded July 9, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“Jimmie’s Mean Mama Blues” (Victor 23503), recorded July 10, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“The Mystery of Number Five” (Victor 23518), recorded July 11, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“Blue Yodel No. 8” (Victor 23503), recorded July 11, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“In the Jailhouse Now, No. 2” (Victor 22523), recorded July 12, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“Blue Yodel No. 9” (Victor 23580), recorded July 16, 1930, at Los Angeles, California.

“T.B. Blues” (Victor 23535), recorded January 31, 1931, at San Antonio, Texas.

“Travellin’ Blues” (Victor 23564), recorded January 31, 1931, at San Antonio, Texas.

“Jimmie the Kid” (Victor 23549), recorded January 31, 1931, at San Antonio, Texas.

“Why There’s a Tear in My Eye” (Bluebird 6698), recorded June 10, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“The Wonderful City” (Bluebird 6810), recorded June 10, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“Let Me Be Your Sidetrack” (Victor 23621), recorded June 11, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“Jimmie Rodgers Visits the Carter Family” (Victor 23574), recorded June 12, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers in Texas” (Bluebird 6762), recorded June 12, 1931, at Louisville, KY.

“When the Cactus Is in Bloom” (Victor 23636), recorded June 13, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“Gambling Polka Dot Blues” (Victor 23636), recorded June 15, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“Looking for a New Mama” (Victor 23580), recorded June 15, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“What’s It?” (Victor 23609), recorded June 16, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“My Good Gal’s Gone - Blues” (Bluebird 5942), recorded June 16, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“Southern Cannon-Ball” (Victor 23811), recorded June 17, 1931, at Louisville, Kentucky.

“Roll Along, Kentucky Moon” (Victor 23651), recorded February 2, 1932, at Dallas, Texas.

“Hobo’s Meditation” (Victor 23711), recorded February 3, 1932, at Dallas, Texas.

“My Time Ain’t Long” (Victor 23669), recorded February 4, 1932, at Dallas, Texas.

“Ninety-Nine Years Blues” (Victor 23669), recorded February 4, 1932, at Dallas, Texas.

“Mississippi Moon” (Victor 23696), recorded February 4, 1932, at Dallas, Texas.

“Down the Old Road to Home” (Victor 23711), recorded February 5, 1932, at Dallas, Texas.

“Blue Yodel No. 10” (Victor 23696), recorded February 6, 1932, at Dallas, Texas.

“Home Call” (Victor 23681), recorded February 6, 1932, at Dallas, Texas.

“Mother, the Queen of My Heart” (Victor 23721), recorded August 11, 1932, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Rock All Our Babies to Sleep” (Victor 23721), recorded August 11, 1932, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Whippin’ That Old T.B.” (Victor 23751), recorded August 11, 1932, at Camden, New Jersey.

“No Hard Times” (Victor 23751), recorded August 15, 1932, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Long Tall Mama Blues” (Victor 23766), recorded August 15, 1932, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Peach-Pickin’ Time Down in Georgia” (Victor 23781), recorded August 15, 1932, at Camden, New Jersey.

“Gambling Barroom Blues” (Victor 23766), recorded August 15, 1932, at Camden, New Jersey.

“I’ve Only Loved Three Women” (Bluebird 6810), recorded August 15, 1932, at Camden, New Jersey.

“In the Hills of Tennessee” (Victor 23736), recorded August 29, 1932, at New York, New York.

“Prairie Lullaby” (Victor 23781), recorded August 29, 1932, at New York, New York.

“Miss the Mississippi and You” (Victor 23736), recorded August 29, 1932, at New York, New York.

“Sweet Mama Hurry Home (or I’ll Be Gone)” (Victor 23796), recorded August 29, 1932, at New York, New York.

“Blue Yodel No. 12” (Victor 24456), recorded May 17, 1933, at New York, New York.

“The Cowhand’s Last Ride” (Victor 24456), recorded May 17, 1933, at New York, New York.

“I’m Free (From the Chain Gang Now)” (Victor 23830), recorded May 17, 1933, at New York, New York.

“Dreaming With Tears in My Eyes” (Bluebird 7600), recorded May 18, 1933, at New York, New York.

“Yodeling My Way Back Home” (Bluebird 7280), recorded May 18, 1933, at New York, New York.

“Jimmie Rodger’s Last Blue Yodel” (Bluebird 5281), recorded May 18, 1933, at New York, New York.

“The Yodelling Ranger” (Victor 23830), recorded May 20, 1933, at New York, New York.

“Old Pal of My Heart” (Victor 23816), recorded May 20, 1933, at New York, New York.

“Old Love Letters (Bring Memories of You)” (Victor 23840), recorded May 24, 1933, at New York, New York.

“Mississippi Delta Blues” (Victor 23816), recorded May 24, 1933, at New York, New York.

“Somewhere Down Below the Dixon Line” (Victor 23840), recorded May 24, 1933, at New York, New York.

“Years Ago” (Bluebird 5281), recorded May 24, 1933, at New York, New York.

Song Title- Recording Artist- Chart Year

Blue Yodel (T For Texas)- Jimmie Rodgers- 1- 1928

In The Jailhouse Now Webb Pierce- 1- 1955

New Mule Skinner Blues- Dolly Parton- 3 1970

T For Texas- Grandpa Jones- 5- 1963

The Brakeman's Blues- Jimmie Rodgers –7- 1928

In The Jailhouse Now- Jimmie Rodgers- 7- 1955

In The Jailhouse Now- Johnny Cash- 8- 1962

The Soldier's Sweetheart- Jimmie Rodgers- 9- 1927

Blue Yodel No. 3- Jimmie Rodgers- 10- 1928

In The Jailhouse Now- Jimmie Rodgers- 14- 1928

Waiting For A Train- Jimmie Rodgers- 14- 1929

In The Jailhouse Now- Sonny James 15- 1977

Roll Along, Kentucky Moon- Jimmie Rodgers 18- 1932

Anniversary Yodel (Blue Yodel No. 7)- Jimmie Rodgers- 19- 1930

T For Texas- Tompall & Outlaw Band- 36- 1976

Miss The Mississippi And You- Crystal Gayle- 3- 1979 (album)