The Hill Billies/Al Hopkins Bios- 1925

“Hear, folks, the music of the Hill Billies! These rollicking melodies will quicken the memory of the tunes of yesterday. The heart beats time to them while the feet move with the desire to cut a lively shine. These here mountaineers sure have a way of fetching music out of the banjo, fiddle, and guitar that surprises listeners, old and young, into feeling skittish. Theirs is a spirited entertainment and one you will warm to.” Okeh “Old-Time Tunes” catalogue April, 1925.

On Jan 8, 1925 when Ernest Stoneman returned to Okeh’s NYC studio and re-waxed “The Titanic” at a slower tempo, he also recorded “Me and My Wife” and “Freckle-Faced Mary Jane,” two songs he learned from his friend and protege Joe Hopkins. Joe and his brother Al had started a band and wanted to do a recording. Okeh and Ralph Peer had heard about the group- later dubbed the Hill Billies: John Rector, their banjoist, had recently recorded for Okeh backing up Henry Whitter; Ernest Stoneman was one of the groups mentors. Stoneman, who would later become a talent scout for Peer, [Ralph would soon quit Okeh and move to Victor] surely made an endorsement of the group since he has recently recorded two of band member John Hopkins’ songs. The next week on Jan. 15, 1925 Ralph Peer invited the Hopkins brothers and their band to the studio.

On their way to their session in New York City they stopped to visit their father in Washington DC. Hopkins’ father asked his son Al, “What do you think you hillbillies can do up there?” His father’s words echoed in bandleader Al Hopkins’ mind several days later in New York City when Peer asked him what he should call the group, and got the response “We’re nothing but a bunch of hillbillies from North Carolina and Virginia; call us anything.” It was Peer who then came up with the official name for the band: The “Hill Billies.” Soon the name would come to describe all early country music and its musicians.

It’s ironic that a string band whose bandleader Al Hopkins played piano and came from an upper class family would be identified with the term. At first the members of the group didn’t like the name. They didn’t want to be regarded as uneducated, backward, country bumpkins. Band members Al, John and Joe Hopkins were the sons of a former state legislator from NC, John Benjamin Hopkins, who was employed as a census taker in Washington, DC. The Hopkinses were originally from Ashe County, NC but grew up in Washington DC. Another member Alonzo Elvis “Tony” Alderman was the son of a surveyor, civil engineer and justice of the peace. When they returned to Galax their friend and mentor Earnest Stoneman assured them, “You couldn’t have ever got a better name.”

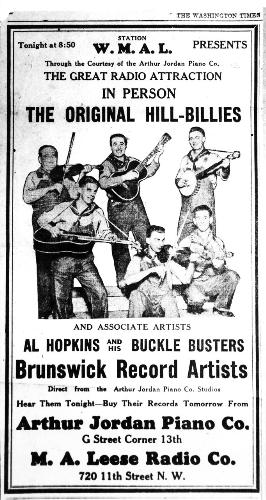

Still, the group felt that folks in Galax wouldn’t approve. Fiddler Tony Alderman thought hillbilly was a “fighting word” and later recalled, “I was afraid to go home as the country people played and sang this type of music. And now I had gone to New York and put their music on records and called it a bad name to boot. So I just didn’t go home for four years.” [The band was stationed out of the Hopkins home in Washington DC.] During the next year the band later known as Al Hopkins and His Buckle Busters finally embraced the name. In the next publicity photo of the group, taken outdoors, shows them clowning around wearing overalls and Tony’s hat’s on backwards. Clearly, they were having fun as hillbillies.

Peer, ever the astute businessman, used similar publicity when describing the Carter Family at their debut recording in Bristol in 1927 saying “He was dressed in overalls, and the women are country woman from way back there- calico clothes on- the children are very poorly dressed. They look like hillbillies.” In fact The Carters dressed up for the occasion and A.P. was wearing a tie. According to Wolfe; “Peer realized that the commercial appeal of this newly-discovered old-time music lay in its rustic, mountain quality.”

Early Years

John Benjamin Hopkins (1858-1934), farmer, house-builder, and North Carolina state legislator, like many of his Watauga County neighbors knew the songs and fiddle tunes prevalent in the Blue Ridge Mountains. [Most of the next sections are from Archie Green’s Hillbilly: Source and symbol; used with permission from the author.] His wife, Celia Isabel Green Hopkins (1863-1953), knew the old ballads and church music as well as her husband's repertoire. After their marriage in 1878, they reared a large family of boys and girls, all with musical talent. In 1904 the elder Hopkins moved the brood to Washington, D.C., where he found employment in the Census Bureau. His hobby was organ building, and he taught several of his boys piano and organ tuning. Seemingly, they taught themselves to play any available instruments. In 1910 Al, Joe, Elmer, and John – ages twenty-one through eleven – formed an Old Mohawk Quartet and began entertaining in Washington's Majestic Theater. Music was to remain Al's main concern for the rest of his short life.

About 1912 Mr. Hopkins built a large family house at 63 Kennedy Street in Washington's then open-field Northwest section. In the hot summers Mrs. Hopkins took the younger children back to their Gap Creek home farm. Daughter Lucy, until her recent retirement a Washington public school music teacher, recalls a variety of fiddle tunes, hymns, old ballads, and pop songs from both homes. In the early 1920's the eldest son, Jacob, had established a country hospital-clinic in Galax, Virginia. Many anecdotes cluster about his early use of musical therapy – bringing local banjo players into the hospital to cheer his patients. Doctor Hopkins was renowned and active as a surgeon and musician. As his practice grew, he brought his brother Al down from Washington to act as hospital office manager and secretary. Meanwhile, brother Joe, a Railway Express agent at White Top Gap, Virginia, had become an itinerant guitarist between regular jobs. He, too, gravitated towards his brother's office on his "bustin" trips.

On a Monday morning in the late spring of 1924, Joe found himself in a Galax barber shop where one of the young journeyman, Alonzo Elvis "Tony" Alderman, kept a fiddle on the wall. The guitarist and fiddler became friends at once, formed a duet on the spot, and began to make music. Tony cut no hair that week. On Saturday Al came for a shave – and for his brother – and joined in the harmony. Word of the new trio reached John Rector, a Fries general store keeper and five-string banjo player of local renown. In fact John had just recently returned from New York City where he, Henry Whitter, and James Sutphin had made three string-band records for Okeh as The Virginia Breakdowners. There seemed to be a great deal of competition among the Grayson-Carroll musicians. Rector felt that the Alderman-Hopkins' talent and his banjo could outshine the Breakdowners. Since he was looking for an opportunity to make the exciting New York trip to stock up on fall merchandise, he asked Al, Tony, and Joe if they wanted to record.

Victor Session

The group’s first recording session in New York was awkward and a bit lackluster. It took three days in Al’s 1921 model T Ford to reach the city where Rector had arranged an audition with Clifford Cairns, Victor A& R man. In the studio Joe, John, and Tony used guitar, banjo, and fiddle while Al took vocal leads as well as acting as the group’s leader. Also he turned the piano into a country music instrument—a precedent infrequently followed by subsequent string-bands. Good techniques for recording mountain string-bands were not yet perfected in 1924. The music was still relatively unknown in the industry; there were problems with balance and placement.

The boys were agreeable, for they preferred music to their respective trades. Tony's musical skill was considerable. As a lad he had played the trumpet in his father's Dixie Concert (brass) Band. From his many uncles and a particular family friend, Ernest V. "Pop" Stoneman, he had learned to fiddle at mountain dances. Tony's memory of the summer New York trip is both clear and amusing. It took three days in Al's 1921 model T Ford to reach the city where Rector had arranged a session with Clifford Cairns, Victor A & R (Artist and Repertoire) man. In the studio Joe, John, and Tony used guitar, banjo, and fiddle while Al took vocal leads as well as acting as the group's leader. Also he turned the piano into a country music instrument – a precedent infrequently followed by subsequent string bands. Good techniques for recording mountain string bands were not yet perfected in 1924. The music was still relatively unknown in the industry; there were problems in balance and placement. Tony recalls the scene:

“We played in front of a big horn, banjo ten feet back in the corner. I was fiddling like mad on a fiddle with a horn on it, which I couldn't hear. John Rector couldn't hear me either, and no one could hear the guitar. Nobody could hear anybody else, to tell the truth. Victor played the record back to us and my father could have done better on his own Edison! (No reflection on Victor; it was us.) So we went home a little sad and ashamed that we had not done better.”

The Victor sessions were not kept or entered in their files; it was more like an audition- they choose not to use. Fortunately, the quartet was not daunted by its failure.

First Okeh Session

In January, 1925, they planned a trip to the Okeh studio – this time in Rector's new Dodge. The weather was cold; hence they improvised a hot brick heater for the journey. To break the long trip from Galax north, they descended on the Hopkins family residence in Washington for shelter. Mr. Hopkins asked his two sons and their mountain companions, "What d'you hillbillies think you'll do up there?" His paternal jibe was to prove effective. In the city, having learned from their previous failure with Victor, the band members were in good form. Ralph Peer supervised the session and recorded six pieces. At the end of the last number Peer asked for the group's name. Al was unprepared. They had no name and he searched for words. "We're nothing but a bunch of hillbillies from North Carolina and Virginia. Call us anything." Peer, responding at once to the humorous image, turned to his secretary and told her to list The Hill Billies on her ledger slips for the six selections. The recording-christening date was January 15, 1925; labels, as well as dealer release sheets, were soon printed and by February the first disc with the new band name was on the market.

The band was not entirely sure of their new name and was somewhat worried about how people in the South would decipher the word. Tony seemed particularly sensitive: “Hillbilly was not only a funny word; it was a fighting word.” Although he had grown up in an isolated log cabin at River Hill, ten miles southwest of Galax, he was in no sense back-woodsy or backwards. His father, Walter, was a self-educated surveyor and civil engineer, a justice of the peace, and a man of literary and musical skill. Tony felt that his family might be critical of the undignified name selected up North and half wished that he could reach Peer to alter the band’s name.

The band did receive positive reinforcement from a hometown friend, Pop Stoneman. Stoneman had already journeyed north on September 1, 1924, to record for Okeh “The Ship That Never Returned/The Titanic.” He, too, like Rector, had felt that he could improve on Whitter. Stoneman’s first record was not yet released at the time of the Hill Billies’ Okeh session. Naturally he was most curious about their luck with Peer. In response to his query, they reported success and the christening of their name, “The Hill Billies.” Pop laughed until tears came too his eyes. “Well boys, you have come up with a good one. Nobody can beat it.”

Listed by Okeh as the Hill Billies with Vocal Chorus by Al Hopkins, they specialized in playing fast breakdowns: “Old Joe Clark;” “Silly Bill;” “Cripple Creek;” “Whoa, Mule;” “Sally Ann;” and “Old-time Cinda” (Cindy).

Following the New York success the band put on its first live show in a Carroll County high school under its Peer-selected name. After their brother Jacob Hopkin’s died their was no reason to stay in the Galax area and Al moved the band to Washington DC. He now turned his father's home into band headquarters, and following the release of their initial record the boys began a heavy schedule of personal appearances in nearby states, as well as radio work in the Capitol City. About March 1925, as The Hill Billies, they made their broadcast debut on WRC with the theme song, "Going Down The Road Feeling Bad" and began broadcasting regularly on Saturday nights. Al's mother frequently accompanied her boys to the station and joined in singing the old ballads that were interspersed between the breakdown instrumentals and humorous skits. Fan mail began to come in addressed to The Hill Billies. Simultaneously, record buyers and radio listeners responded to the new association, hillbilly music.

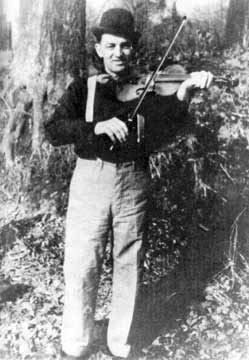

Charlie Bowman

On May 8, 1925, the Hill Billies, stars of WRC, were invited to a tremendous fiddlers convention in Mountain City, Tennessee. At the gathering Charlie Bowman (born July 30, 1889, Gray Station, Tenn., died May 20, 1962 Union City, Ga.) a young country fiddler from Gray Station, near Johnson City, Tennessee, joined the band. He was the first of many newcomers to augment the original group's rank. Not only did he contribute his fine talent and humor at that time, but in later years he was to convey much of the band's story to discographers and folklorists.

Bowman, who quickly became the star of the group, was born in 1889 in Fordtown, Tennessee and came from a talented family of musicians. He won 28 of the first 32 fiddle contests he entered and played originally with his band, Charlie Bowman and His Brothers. In addition to the fiddle, Charlie could also play 15 standard and several not-so-conventional instruments, including brooms, saws, washtubs, thick balloons, a homemade one-string bass, and even an underfeed furnace. Charlie displayed his comedic talent in the song, “Donkey On the Railroad Track,” a skit recorded on Vocalion Records on October 23, 1926. Al Hopkins provided the narrative, and Charlie imitated both the train and the donkey on his fiddle. A favorite of the audience was when Charlie and Tony Alderman stood one behind the other and bowed each other’s fiddle yet fingered his own fiddle.

Following Mountain City a heavy schedule of personal appearances from South Carolina to New York commenced – at schools, vaudeville shows, fiddlers' competitions, political rallies, and even a White House Press Correspondents' gathering before President Coolidge. Much of the roadwork was correlated with trips to New York for recording sessions. A March 6, 1926 Radio Digest article titled “Hill Billies Capture WRC”. A subtitle said “Boys from Blue Ridge Mountains Take Washington with Guitars, Fiddles, and Banjos; Open New Line of American Airs”. Response to the broadcast was amazing with letters, postcards, and phone calls pouring in to the station from a wide area.

Vocalion- Al Hopkins And His Buckle Busters- 1926

After Peer left Okeh in 1925 the Hill Billies signed with A&R man Jimmie O'Keefe at Vocalion/Brunswick and had their first session on April 30, 1926 with Bowman and Alderman playing twin fiddles. They cut some of their finest music including their hit, “Mountaineer’s Love Song,” a version of “Goodbye Liza Jane,” backed by “Cripple Creek.”

All their post-Okeh discs were released for dual sales purposes as The Hill Billies on Vocalion and as Al Hopkins and His Buckle Busters on Brunswick. For personal dates they used both names interchangeably. During one New York recording session they were surprised to see on the Hippodrome Theater marquee lights, The Ozark Hillbillies. They responded to the competitive threat by having a Washington lawyer incorporate (January 21, 1929) their group – complete with an embossing seal and stock shares – as Al Hopkins' Original Hill Billies. But the gesture was of no avail. Other bands, singers, and units in show business appropriated their name. In time, they accepted the rivalry philosophically – especially when hillbilly became the generic term for southern country music.

In 1927, Jack Reedy was recruited to play banjo with The Hill Billies, replacing Tony Rector. In May of 1927, the group traveled to New York City to make recordings for the Brunswick and Vocalion labels, including a fine rendition of Cluck Old Hen, a tune that would become Jack Reedy's signature piece. The record showcased Reedy's skillful fingerpicking and the twin fiddles of Alderman and Bowman, with Al Hopkins providing vocals and Al's brother John Hopkins on ukulele. Another change was Bowman’s brother, Elbert, playing guitar.

Banjoist Jack Reedy also played at the 1928 Bristol Sessions with Smyth County Ramblers featuring fiddler Jack Pierce of the Tenneva Ramblers and guitarist Malcom Warley and Carl Cruise from Damascus, Va. Reedy was born in 1895 in the Grassy Creek community of North Carolina. He was a three-finger picker and would record with many other groups. As a boy he learned to play on a homemade banjo with a head made of groundhog hide. He spent most of his life in Marion, Virginia, which is in Smyth County. The Smyth County Rambers would go on to fame as the Southern Bucaneers. Reedy also recorded for Brunwick (Jack Reedy and His Walker Mountain String Band) in Ashland Ky on Feb. 1928 Chinese Breakdown and Ground Hog with Fred Roe, Frank Wilson and Walter “Sparkplug” Hughes. The last session was Jack Reedy and His River Boys Knoxville TN April 7, 1930 both songs were not released. Reedy and Frank Blevins achieved some notoriety for performing for first Lady Eleanor Roosevelt at the White Top Folk Festival and by making a Paramount newsreel.

In the late 1920’s Hill Billies were national stars. They performed at a White House social before President Calvin Coolidge. Warner Brothers asked them to make a fifteen- minute Vitaphone “short” for the Al Jolson movie “The Singing Fool,” appropriately called “The Hill Billies.” It was certainly the first movie to couple the sound and sights of hillbilly music. Each time the band went to New York City to record for Vocalion and Brunswick, the Broadway Theatre booked them for performances.

The 1929 Depression curtailed their recording career. A few years later Al Hopkins died following a car accident at Winchester, Virginia in 1932. The band did not survive his death. The Hill Billies made several important contributions to early Country Music. Bowman’s “East Tennessee Blues” is still widely recorded and is a bluegrass standard. The group was the first to record “Nine Pound Hammer” and the companion song “Roll on Buddy” from a tune Bowman had heard from some railroad workers. They were one of the first groups to use steel or Hawaiian guitar when Frank Wilson played in their recording sessions.

The Hillbillies Complete Discography (Al Hopkins and His Buckle Busters) 1925-1928:

Baby Your Time Ain't Long; Betsy Brown; Black Eyed Susie; Blue Bell; Blue Eyed Girl; Blue Ridge Mountain Blues; Boatin’ Up the Sandy; Bristol Tennessee Blues; Buck-Eyed Rabbits; Bug In The Taters; Buffalo Gal(s); Cackling Hen; Carolina Moonshiner; C. C. O. No. 558; Cinda; Cluck Old Hen; Cripple Creek; Cumberland Gap; Daisies Won't Tell; Darling Nellie Gray; Donkey On The Railroad Track; Down The Old Meadow Lane; Down To The Club; East Tennessee Blues; Echoes Of The Chimes; Feller That Looked Like Me; Fisher's Hornpipe; Georgie Buck; Gideon's Band; Going Down The Road Feeling Bad; Governer Alf Taylor's Fox Chase; Hear Dem Bells; Hickman Rag; Johnson Boys; Kitty Wells; Kitty Waltz; Long Eared Mule; Lynchburg Town; Marosovia Waltz; Medley Of Old Time Dance Tunes (Intro: Soldier's Joy - Turkey Buzzard - When You Go A Courtin'); Mississippi Sawyer; Mountaineer's Love Song; Nine Pound Hammer; Oh Didn’t he Ramble; Oh Where Is My Little Dog Gone; Old Dan Tucker; Old Joe Clark; Old Uncle Ned; Old Time Cinda; Polka Medly (Intro: Rocky Road To Dublin, Jenny Lind); Possum Up A Gum Stump, Cooney In The Hollow; Ragged Annie; Ride That Mule; Roll On The Ground; Round Town Girls; Sally Ann; Silly Bill; She'll Be Comin' 'Round The Mountain; Shoot the Turkey Buzzard; Silly Bill; Sleep Baby Sleep; Soldier's Joy; Sourwood Mountain; Sweet Bunch Of Daisies; Texas Gals (Texas Gales); Walking in the Parlor; Wasn’t She A Dandy; Western Country; West Virginia Gals; When You Were Sweet Sixteen; Whoa! Mule; Wild Hoss

Charlie Bowman: Boys, My Money's All Gone; Caroline Moonshine; Forked Deer; Hickman's Rag; Moonshiner and his Money; Money Musk; Nancy Rowland; Possum Up A Gum Stump; Raise a Ruckus (Tonight); Roll On Buddy; Wild Horse;

Bowman Sisters (With Charlie Bowman): Old Lonesome Blues; Railroad Take Me Back