Carolina Tar Heels Biographies-1927

The Carolina Tar Heels recorded their first sides on Feb. 19, 1927 for Ralph Peer on Victor Records. Atlanta was the first of three southern locations Peer brought his new portable recording system. The Tar Heels featured a cast of talented Country musicians revolving around three-finger banjo virtuoso Dock (Doctor Coble) Walsh. In 1925 Walsh made his first recordings for Columbia as a solo artist and formed the Carolina Tar Heels with harmonica wizard Gwen Foster and Tom Ashley. Ashley was not present at the first session so Foster played harmonica and guitar with Walsh playing banjo.

Eventually Garley Foster (no relation) replaced Gwen Foster. Coincidentally both men played harmonica (French harp) and guitar. One of the unusual things about the Carolina Tar Heels was the absence of a fiddler, standard fare for most early string bands. Gwen Foster has been recognized as one of the finest harmonica players in early Country Music. His “Wilkes County Blues,” and the Tar Heel’s “Drunk Man Blues” or “My Sweet Farm Girl” showcase Fosters brilliant harmonica work.

The career of Walsh was rivaled by band member Clarence (Tom) Ashley who would record solo (banjo and vocal) and with Gwen Foster, also with Byrd Moore and his Hot Shots, The Blue Ridge Entertainers and later in the 60s with Doc Watson, Clint Howard, Fred Price and Gaither Carlton. Ashley also played an important role introducing songs like “Rising Sun Blues (House of the Rising Sun),” “Little Sadie,” “Dark Holler,” and “Greenback Dollar.” A new CD is out entitled Greenback Dollar which chronicles Ashley’s recordings with different groups from 1928 to 1933.

The Carolina Tar Heels

The Carolina Tar Heels featured a rotating group of four musicians from the North Carolina mountains: Dock Walsh (banjo and lead vocals); Gwen Foster (guitar, vocals and harmonica); Tom Ashley (banjo; guitar and lead vocals) and later Garley Foster (guitar, harmonica vocals) who replaced Gwen Foster (they are not related). Ralph Peer named the group (Walsh and Gwen Foster) at their first Victor session in Atlanta. According to some sources Walsh and Tom Ashley met at a fiddler's convention in 1925. Later he asked Ashley to join the Tar Heels as a guitarist and singer (both vocal lead and harmony). The Carolina Tar Heels made 18 records (36 songs) in seven sessions for the Victor label (Feb. 19, 1927 in Atlanta; Aug. 11-14 1927 in Charlotte; Oct 10-14, 1928 in Atlanta; Nov. 14, 1928 in Atlanta; April 4, 1929 in Camden, NJ; Nov. 19, 1930 Memphis and lastly Feb. 25, 1932 in Atlanta). The last two sessions were made after the Great Depression (Oct. 1929) which was largely responsible putting an end to the recordings of The Carolina Tar Heels. Most groups folded in the early 1930s and looked for suitable work outside the music business.

Ashley wasn’t present at the first sessions in 1927, which were made by Dock Walsh and Gwen Foster, or the last in 1932. Some of the songs recorded for Columbia by Walsh in 1925 and 1926 were recorded again for Victor with different titles (“Going Back to Jericho” became “Back To Mexico”) to avoid copyright infringement. Individual members of the group (Ashley with Byrd Moore and his Hot Shots and solo for Columbia at The Johnson City Sessions in 1929 and Gwen Foster with the Carolina Twins) would make records with different groups until the Ashley- Gwen Foster sessions for Vocalion in Sept. 1933.

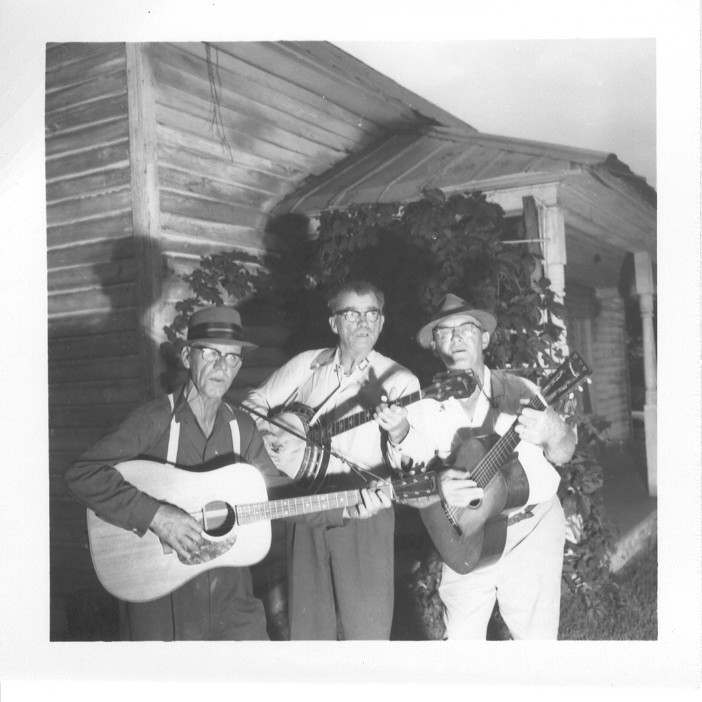

During the 1960s folk revival Walsh reorganized the Carolina Tar Heels with his son Drake and former member Garley Foster. The new band recorded an LP for Folk Legacy produced by Eugene Earl and Archie Green. I interviewed Green briefly and obtained his permission to use the liner notes, which I received from Sandy Patton. Many of the original Tar Heel’s songs were covered on the 1962 recording. “Gene had an Ampex recorder and I was his assistant,” recalled Green. “I remember Dock telling me, ‘Wilkes County has a lot of moonshiners’, they claimed it was moonshine capital of the world. We recorded a bunch of songs and picked out what we thought were the most representative.”

Complete Recordings of The Carolina Tar Heels (Gwen Foster; then Garley Foster; Doc Walsh; Tom Ashley) Back To Mexico; Bring Me A Leaf From The Sea; Bulldog Down In Sunny Tennessee; Can’t You Remember When Your Heart Was Mine; Farm Girl Blues; Goodbye My Bonnie, Goodbye; Got The Farm Land Blues; Hand In Hand We Have Walked Along Together; Hen House Door Is Locked; Her Name Was Hula Lou; I Don’t Like The Blues No How; I Love My Mountain Home; I’ll Be Washed; I’m Going To Georgia; Lay Down Baby Take Your Rest; My Home’s Across The Blue Ridge Mountains; My Mama Scolds Me For Flirtin’; Nobody Cares If I’m Blue; Oh How I Hate It; Old Grey Goose; Peg And Awl; Roll On Boys; Rude And Rambling Man; She Shook It On The Corner; Shanghai To China; Somebody’s Tall And Handsome; There Ain’t No Use Workin’ So Hard; There’s A Man Goin’ Round Takin’ Names; Times Ain’t Like They Used To Be; Train’s Done Left Me; Washing Mama’s Dishes; Who’s Gonna Kiss Your Lips Dear Darling; When The Good Lord Sets Me Free (Shout Mourner); Why Should I Care; You Are A Little Too Small; Your Low Down Dirty Ways;

Dock Walsh- Biography

A Wilkes County, NC musician born on a farm in Lewis Fork (now named Ferguson) to Lee Walsh and Diana Elizabeth Gold Walsh on July 23, 1901, Doctor “Dock” Coble Walsh was one of eight children who played music. His first banjo, fretless and made out of an axle grease box, was given to him by his older brother when he was just four years old. As a teen he began playing banjo and singing locally where earned some money performing. Besides his trademark three-finger style, Dock played "knife-style" or slide banjo on some of his recordings by placing pennies under the instrument's bridge and playing the strings with a knife, somewhat similar to bottle-neck slide guitar playing.

When Dock was in his teens he started playing at dance parties with his friends and alone; sometimes he earned some money. Soon he bought a good Bruno banjo in Lenior, which he used until his 1925 recording sessions. In 1921 Dock became a public school teacher after receiving his teaching certificate at Mountain View. After he heard Henry Whitter’s recording of “Wreck of the Old 97” on Okeh Records, Dock became determined to make a record.

He wrote Okeh and then Columbia records but got no response. Undeterred, he quit his teaching position and moved to Atlanta where both companies did field recordings and got a job working in cotton fields. After six months he arranged an audition with Columbia’s Bill Brown. On October 3, 1925, he recorded four songs under the supervision of Frank Walker, who put pillows under his feet to "stop the racket” Walsh made keeping time with his shoe heels. His first single was “I’m Free At Last,” backed by “East Bound Train.” He next did a parody of “The Girl I Loved In Sunny Tennessee” called “Bulldog Down In Sunny Tennessee” and “Educated Man,” a version of “I’m A Highly Educated Man” known as “I Was Born 4,000 Years Ago.” After his triumphant recording session he walked home from Atlanta to Wilkes County; a distance of over 300 miles!

No longer interested in teaching, Walsh devoted himself to being a professional musician. He traveled the highways and byways, entertaining lumber haulers and sawmill workers along the way. The Columbia catalogue for 1927 read: “Dock Walsh is hard to catch. So great is the demand for him at country-dances and entertainments in the South, that it’s mighty hard to tell where he’ll be next. However when you catch him, it’s worth all the trouble.”

He played primarily in the claw hammer style but along with Charlie Poole and Dock Boggs, was another forerunner of the three-finger style. On April 17, 1926 Walsh once again returned to Atlanta to wax “We Courted in the Rain,” “Knocking on The Henhouse Door,” “Going Back To Jericho,” “Traveling Man” and the very first recording of “In The Pines” for Columbia. He met some of the musicians soon to be named the Skillet Lickers including Riley Puckett, Clayton McMichen, Gid Tanner and Fate Norris.

In the summer of 1926 Dock was playing banjo and harmonica (on a rack) in Gaston County when a listener offered to take him to see a good harmonica player, Gwen Foster. Gwen, who was a doffer in a Dallas NC mill, began playing with Walsh. They teamed up with two Gastonia area guitarists, Dave Fletcher and Floyd Williams forming the Four Yellowjackets. A Victor talent scout heard them and they traveled to Atlanta where Ralph Peer recorded four duets with Foster and Walsh naming them the Carolina Tar Heels.

Dock Walsh billed himself as the "The Banjo King of the Carolinas." Charlie Poole, a similar three-finger style mountain banjo picker who also recorded for Columbia in 1925, had a smash hit (selling 102,000 copies) with “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down.” Walsh was well aware of Poole’s career with Columbia and covered one of his songs, “The Girl I Loved In Sunny Tennessee,” with his parody called “Bulldog Down In Sunny Tennessee.” It’s probable that Poole’s success with Columbia was a bone of contention for Walsh as Columbia boasted in their catalogue: Charlie Poole is unquestionably the best-known banjo picker and singer in the Carolinas.

Walsh never again recorded for Columbia. On one concert poster for the original Tar Heels, Dock Walsh was billed as the Banjo King of the Carolinas and Garley Foster as The Human Bird (for his bird calls). In his last solo session Walsh recorded the folk hymn “Bathe in that Beautiful Pool” for Victor on Sept. 25, 1929. The other songs from the session were: “Laura Lou,” “A Precious Sweetheart From Me Is Gone” and “We’re Just Plain Folks.”

Walsh married in 1929 and immediately began raising a family. To make ends meet he went “bustin” or “ballying” on the streets (playing for spare change) with Garley. On May 30, 1931 Walsh and Garley Foster also recorded under the name, Pine Mountain Boys, which curiously is the same line-up as the next to last Carolina Tar Heel session in November 1930. The five songs that emerged from the session were: “The Gas Run Out,” “She Wouldn’t Be Still,” “Roll On Daddy Roll On,” The Apron String Blues” and “Wild Women Blues.”

After his recording career ended in the early 1932, Walsh worked in the poultry business to support his growing family- two boys and two girls. Later in the 1950s he became an outside salesman for a North Wilkesboro auto parts firm, C.D. Coffee and Sons.

After decades of inactivity, Dock the group reformed in 1961. Walsh has been dead for several years but played at the Union Grove Old Time Fiddlers Convention as recently as 1959. The second generation of the Carolina Tar Heels featured his son, Drake Walsh of Millers Creek, recently a member Elkville String Band as well as original member Garley Foster. They recorded an album for Folk Legacy in 1964. Drake, born on Dec. 28, 1930, played fiddle and guitar, played with his Danc-A-Lons at the North Wilkesboro VFW on Saturday nights.

New Carolina Tar Heels Recordings (Dock Walsh, Drake Walsh, and Garley Foster) Recorded in sixties by Eugene Earl and Archie Green for Folk Legacy): Ain't Gonna Be Treated This A-Way; Bull Dog Down in Sunny Tennessee; Courtin' in the Rain; Crescent Limited; Dango; Drake's Reel; Garley's Fox Chase; Go Wash in That Beautiful Pool; Goin' to Georgia; I Was Born About 4000 Years Ago; If I Was a Mining Man; Jimmy Settleton; Knockin' On the Henhouse Door; Mama Scolds Me For Flirtin'; My Brushy Mountain Home; This Morning- This Evening -Right Now; Hide-A-Me

Gwen Foster- Biography

Besides being one of the finest early harmonica players Gwen Foster was also an excellent guitarist and singer. He played 2nd guitar or back-up guitar on the Tar Heel recordings. Foster used a “rack” to hold his harmonica so he could play guitar at the same time. His friend David McCarn (composer of “Cotton Mill Colic” and “Everyday Dirt”) recalled that with his dark skin, and an oriental look to him, Gwen acquired the nickname "China" pronounced “Chinee.” McCarn worked with Foster at the Victory Mill in South Gastonia said Gwen “entertained them when the work slowed down and they thought his French harp (harmonica) was as powerful as a pipe organ. Gwen ruined a flour barrel full of harps by his constant playing” [Archie Green]. Although Gwen Foster was a musical genius, he drank too heavily at times. Tom Ashley would laugh and tell about sobering him up on cider and moonshine before they went to play.

Foster was a mill worker like many musicians (Charlie Poole, Henry Whitter) from the Gastonia, NC area. One of the favorite gathering places for Foster and other local musicians was in front of Lackey's Hardware Store in Old Fort, North Carolina. Regulars at Lackey's were Foster on guitar and harmonica, Clarence Greene on fiddle and Roy Neal on three-finger style banjo. Occasionally, musicians from out of town, like Will Abernathy, who played the autoharp, would join the mob assembled on the front porch of the store. The musicians left a hat out front for bystanders to pitch a penny but never made much money from it.

Foster became known for his playing and drinking as well as his antics. At Lackey's he first met talented guitarist Walter Davis. The two musicians became fast friends and frequently could be found playing on street corners for pennies all across North Carolina. Walter remembers one time in particular when they were together in Morganton, North Carolina:

"Me and Gwen were in Morganton one time broke, and looking for some way to make a little money. Gwen said he knew of a way to make some money fast. He was going to pretend that he was blind while we played on the street corner in front of the courthouse. He put on some sunglasses, and told me to pass the hat around. I told him, 'no, you attach the tin cup to your guitar strap and people will sympathize with you more. I don't want any part of this deal.' So he played for a while and some lady came up and tried to put a fifty cent piece in his cup. But she missed the cup and the coin went rolling down the street. Gwen went right after that coin like a man who could see. That lady said something like 'That boy don't look so blind to me.' At that point me and Gwen took off running, and I believe that was our last engagement in Morganton."

Gwen Foster Solo Recordings (Charlotte; August, 1927 on Victor): Black Pine Waltz; Wilkes County Blues

The Carolina Twins

After the Tar Heels Foster played in a duo with David Fletcher, one of the original members of the Four Yellowjackets, called The Carolina Twins. These were credited to 'Fletcher and Foster' -- Gennett, and 'The Carolina Twins' -- Victor. Gwen Foster's importance lies not in some great ability to create original songs, but in his innovation and improvisation in dealing with basically traditional material, and his fine musicianship...Another waltz from the Carolina Twins. Probably this one dates back top the American Civil War. The Song is interesting because Fletcher and Foster have added a yodel which would never have been present in more traditional versions.

The Carolina Twins Recordings (Fletcher and Gwen Foster) Feb. 20, 1928 Victor Records – last session Champion Sept. 23, 1930: A Change Of Business All Around; Boarding House Bells Are Ringing; Charlotte Hot Step; Gal Of Mine Took My Licker From Me; Going A Courtin’; I Sat Upon The River Bank; I Want My Black Baby Back; Mr. Brown Here I Come; New Orleans Is The Town I Like Best; Off To the War I’m Going; One Dark And Rainy Night; Red Rose Rag; She Tells Me I Am Sweet; Since My Baby’s Gone Away; Southern Jack; Travelin’ North; When You Go A- Countin’; Where Is My Mama; Who’s Going To Love Me; Working So Hard; Your Wagon Needs Greasing

The Blue Ridge Mountain Entertainers

From the group that gathered at Lackey’s Hardware store came The Blue Ridge Mountain Entertainers made up of Tom Ashley, guitar and vocals; Clarence Green, fiddle; Gwen Foster, harmonica; Will Abernathy, autoharp and harmonica; and Walter Davis, lead guitar.

The Blue Ridge Entertainers Recordings- Nov. 30, 1931; ARC: Baby All Night Long; Bring Me A Leaf From The Sea; Cincinnati Breakdown; Corrina Corrina; Crooked Creek Blues; Drunk Man Blues; Far Across the Deep Blue Sea (unissued); Goodnight Waltz; Ham and Eggs (unissued); Haunted Road Blues; Honeysuckle Rag; I have No Loving Mother Now; My Sweet Farm Girl; Nine Pound Hammer (unissued); Penitentiary Bound; Short Life Of Trouble; There Will Come a Time (unissued); Washington and Lee Swing; Gwen Foster recorded his last songs fronting a group (probably the Three Tobacco Tags- Luther Baucom, Reid Summey and Sam Pridgin) in Rock Hill SC for Bluebird in Feb., 1939: “How Many Biscuits Can You Eat?” and “Side Line Blues.”

Garley Foster was born in Purlear, Wilkes County, NC on Jan. 10, 1905 only from the Walsh farm. His parents were Gilbert “Monroe” Foster (1885-1975) and Dora Belle Shepherd. Garley’s grandfather owned a mountain store and his grandmother gave him a harmonica when he was a little boy. From his father he learned the fiddle and the banjo. Whne Garley was a teenager he began playing with Dock Walsh, first practicing with him on a log in the woods and then playing with him at square dance parties. In his late teens he began playing guitar and devised a way to play harmonica at the same time before he knew harmonica racks existed. Self taught, he did learn harmonica piece from recordings by DeFord Bailey, the only African-American to ply on the Opry at that time.

After Dock began recording as the Carolina Tar Heels, his partner Gwen Foster who lived far away in Dallas, became difficult to play with. Walsh turned to his old friend and Garley and used him on many subsequent sessions and later in 1962 recorded with him as The Carolina Tar Heels.

On a Carolina Tar Heels promotion poster Garley is called “The Human Bird” for his remarkable birdcalls: “Mr. Foster will entertain you with his mockery of many, many birds including Red Bird, Mocking Bird, Wren, Pewee, Owls, Hawks etc. Also a saw mill in operation. Nothing used in these imitations except the voice. You’ll marvel at the unusual talent Foster will display on the guitar and the harmonica.”

During the Depression years (1929-1933) Dock and Garley performed at fairs, theaters and schools. They had a poster printed entitiled “Look Who’s Coming” with a photo of Garley holding an owl. In May 1931 he made a solo recording of his famous birdcalls for Victor but unfortunately they were never issued. His bird calls can be heard on my “Home’s Across the Blue Ridge Mountain” or on the “My Brushy Mountain Home” LPs.

Besides his solo work across the “bacco belt,” he also played with Clarence Green and Byrd Moore. Garley worked as a carpenter and built roads when he wasn’t playing music. In the 1950s he was a self-employed carpenter in the Taylorsville area.

Clarence "Tom" Ashley- Biography

Clarence "Tom" Ashley (1895-1967) was a revolving member of the Carolina Tar Heels and started recording with them in 1928. He was lead vocalist (which he shared with Dock Walsh) and guitarist for the Tar Heels and also an accomplished banjo picker, entertainer and comedian. During the 40s Ashley even worked as a blackface comedian in the live shows of Charlie Monroe and The Stanley Brothers. Ashley developed his skills as he traveled in the summers with the same medicine show from 1911 to 1943.

Besides Ashley’s importance as a musician he was also the mentor for two future Country Music Hall-Of-Famer’s; Roy Acuff and Doc Watson. It was during Ashley's medicine show days that he played with Roy Acuff, now known as the King of Country Music. Ashley related the experience to a reporter for the Tennessee paper in the following way: Just before one summer, the Doc told me he had a neighbor boy who could sing a little and play a little and said he'd like to take him along. He asked if I'd train him, and I said I would. That boy stayed with us two summers and I taught him some songs, and after that he went off on his own and did right well. He was Roy Acuff. When Ashley was rediscovered by Ralph Rinzler in the 1960s, Tom introduced him to Doc Watson, who is recognized as one of the greatest Country Music guitarists of all time. Watson and Ashley (along with other musicians) would record two albums entitled “Old-Time Music At Clarence Ashley’s.”

Ashley’s Early Life

From the time of Tom Ashley's birth on September 29, 1895, the old-time music and the ballads that were brought to America from the British Isles surrounded him. The Ashley family came to America from Ireland eventually settling in Ashe County, North Carolina. Shortly after the Civil War, Joe Ashley's son Enoch married Tas Robinson's daughter Martha (Mat). Enoch and "Mat" were a musical pair, both singing the old ballads that they had learned from family and friends. This marriage was blessed with three daughters who, like their parents, developed a love for music. Ary and Daisy played the banjo and sang, and Rosie-Belle sang with a beautifully clear voice [Much of this information in this section, though rewritten in part, comes from Minnie M. Miller, August 1973 masters thesis: Tom Clarence Ashley: An Appalachian Folk Musician]

In 1894, Rosie-Belle, the youngest daughter, married George McCurry, an accomplished fiddler. After Rosie-Belle and George had been married about a year, Enoch Ashley acquired information that George was married to at least one other young lady. George was run out of town and Rosie-Belle returned to her father's home. Later, it was suspected that George had given his name in marriage to at least four or five women. On September 29, 1895, shortly after Rosie-Belle returned to her father's home in Bristol, Tennessee, she gave birth to a son, Clarence Earle McCurry. After moving from Bristol back to Ashe County, North Carolina, Enoch Ashley's family finally settled in Mountain City, Tennessee, in 1899. Enoch found work in the local lumberyard and started a boarding house.

Although Rosie-Belle named her son Clarence Earl McCurry, no one knew him by that name. Young Clarence was full of energy and mischief, and his grandfather nicknamed him "Tommy Tiddy Waddy." As Clarence grew older, the "Tiddy Waddy" was dropped, but the "Tommy" stuck. Since Tom was raised by his grandfather and his mother, he used the Ashley name. By the time he was grown, he had completely dropped the Earle from his name and was known as Thomas Clarence Ashley. Early recordings listed him as Tom Ashley or Clarence Ashley. When Rinzler looked for Ashley in the sixties he looked for Clarence Ashley but no in the county even knew that was his name.

When Ashley was a boy, he was ambitious and quick-witted. He dropped out of school in the fifth grade, but he appeared to be a smart boy and learned things exceptionally fast. The year that Ashley dropped out of school, his mother, Rosie-Belle, married a man by the name of Walsh. His first musical instrument was a "peanut banjo" which his grandfather gave him when Ashley was about eight years old. Aunt Ary and Aunt Daisy taught him to play a little banjo; and at the age of twelve, he learned to play the guitar. Ashley learned many of the songs that he knew when he was quite young.

The Ashley's often had people in to sing and play the old songs, and it was seldom that work in the neighborhood was not accompanied with singing and picking. The entire community was often involved in events such as a "lassy-makin." All of these events were usually accompanied by music; and when there was music to be played or a song to be sung, Ashley was right in the middle of it. Ashley jokingly referred to his oldest songs as "lassy-makin' tunes". He tuned his banjo to what he called "saw-mill key" or "lassy-makin'" tuning: DCGDG (starting with the first string and ending with the shorter fifth string).

Ashley Joins the Medicine Show

When Ashley was sixteen, a medicine show came to Mountain City, and before the show left town, Ashley had joined the show as a banjo picker and singer. He first traveled with Doc White Cloud, supposedly a full-blooded Indian. The medicine show had a great deal of influence on Ashley. It was there where he first performed professionally and from that time on he made his living mainly with his music. The medicine show was a seasonal occupation operating during the summer months. It toured small towns in the rural areas, stopping at each place for about one to two weeks. The length of time was determined by how long the people continued to buy medicine. Some of the towns included on the circuit were Hampton, Mountain City, and Greenville, all in Tennessee, and Abingdon, Virginia. If there was a fair going on, the medicine show usually set up outside the fair to sell the medicine. The medicine show started with the entertainers, usually two, on stage doing songs, jokes, and comedy routines. It was with the medicine show that Ashley learned his black-faced comedy act, Rastus. People began to gather as the entertainment got underway on the stage, a platform attached to a wagon. Since there were no seats for people, everyone stood to watch the show. There were usually two entertainers and a Doc. The Doc was always the head of the show. It was his secret formula that prepared the cure-all medicine.

Ashley traveled in the summers with the same medicine show from 1911 to 1943. The ownership of the show changed several times, but the only two Docs that the people of Johnson County can remember were Doc Whitecloud and Doc Hauer. Ashley was never the owner of the show; he was one of the entertainers. Apparently, some class distinction existed in the group because the Doc traveled in a smart horse-drawn carriage, while Ashley and the other entertainer rode in a prairie-schooner covered wagon along with the platform, lanterns, and rigging for the stage. In addition to Ashley's duties as singer, comedian, banjoist, and guitarist, he was responsible for hauling water and feeding the horses.

The medicine shows did not afford the opportunity to become wealthy, but Ashley managed to make a living during the summers by traveling with the shows. During the remainder of the year, Ashley would organize a local band and play wherever they could make a few dollars. When Ashley was in his early teens, he and some other Johnson Countians organized a brass band. They gave shows to earn enough money to pay their instructor to come to Shouns School to teach them. They earned enough money from these shows to pay for their uniforms, instruments, and lessons, with a few dollars left over occasionally.

Ashley Get Married

When Ashley could not earn enough money playing music, he took a job at anything he could find. He was working for the J. Walter Wright Lumber Company at Shouns, Tennessee, when he became friends with a man named Osborne from Ashe County, North Carolina. It was through Osborne that he met his future wife, Hettie. Hettie was Osborne's sister, and about a year after Ashley met her, he married her. Ashley was seventeen, and Hettie was fourteen. They bought a small tract of land from Denver Miller at Shouns and settled there. Ashley continued to make their living by traveling with the medicine shows in the summers and playing with local bands. Hettie stayed home and raised a garden. They had plenty of fresh vegetables in the summer, and she canned and preserved food for the winter. They kept a cow for milk, and they kept chickens for eggs and meat. The responsibility of caring for the garden, milking the cow, gathering the eggs, and killing a chicken now and then usually fell to Hettie since Ashley was "on the road" much of the time.

Ashley Plays with GB Grayson, Others

When there was not enough demand for music to make a living in Johnson County, Ashley set out on a career of what he called 'busting' (commonly called 'busking' in the British Isles). He would sing in the streets, on the edge of carnivals, outside of the main building of mines on pay days for nickels and dimes. During the 1920s, he played a great deal with G.B. Grayson, an accomplished fiddler from Laurel Bloomery, Tennessee. Also, he played with the Cook Sisters from Boone, North Carolina, and with the Greer Sisters. In these trios, Ashley played guitar while the sisters played mandolin and fiddle. Ashley formed a band with Dwight and Dewey Bell known as "The West Virginia Hotfoots." Hobart Smith was another old-time musician Ashely met.

Ashley Recordings

Besides the Carolina Tar Heels sessions Tom Ashley made his fist recordings under his own name for Gennet in Richmond Indiana on Feb 2, 1928. Accompanied by Dwight Bell on banjo, Tom sang and played guitar on the old-time standards “You’re A Little Too Small” and a version of the humorous Our Goodman named “Four Night’s Experience.”

When Frank Walker of Columbia Records conducted the famous Johnson City Sessions on October 23, 1929 Ashely was there, recording with Byrd Moore and his Hot Shots. The group consisted of Byrd Moore, finger style banjo or lead guitar; Clarence Greene, fiddle or guitar; and Clarence T. Ashley, guitar or banjo.

Byrd Moore and his Hot Shots: Careless Love; Frankie Silvers; Hills Of Tennessee; Three Men Went A Hunting

At the session Ashley volunteered some "lassy-makin' tunes" and after demonstrating a song was asked to record solo, accompanied on his five string banjo with a strange "sawmill" tuning. One of the songs produced from this session was his famous recording of "The Coo-Coo Bird." There’s also a video of him made years later of him playing and singing the haunting Appalachian melody.

According to Minnie Miller’s article on Ashley: “The recording company was most impressed with Tom and later wired him to come to New York to make further recordings. They offered him a contract but his friends were not included. Ashley rejected the offer because he felt that they should take all of them or none of them. Tom's son J.D. thinks that his dad might have become a famous recording star if he had accepted the offer of that contract.” The facts are that the Great Depression would negatively effect the recording industry for the next ten years. On April 14, 1930 Ashley went to Atlanta and recorded songs including “The House Carpenter” a song Walsh had already recorded for Columbia by a different title and “Old John Hardy.” Since Ashley did go record more solo recordings for Walker at Columbia, it seems that more likely that prevailing economic climate of the country prevented him from succeeding.

Ashley Solo Recordings Feb 2, 1928- April 14, 1930 Gennett and Columbia: Coo-Coo Bird; Dark Holler Blues; Four Night’s Experience; House Carpenter; (Old) John Hardy; Little Sadie; Naomie Wise; You’re A Little Too Small;

From Nov. 30, 1931 to Dec 2, 1931 Ashley recorded with his friends from the gathering at Lackey’s Hardware Store. The called themselves The Blue Ridge Mountain Entertainers and featured Tom Ashley- guitar banjo vocals, Clarence Greene- fiddle; Gwen Foster- guitar harmonica; Walter Davis-guitar and Will Abernathy- autoharp and harmonica.

Blue Ridge Entertainers (Nov. 30, 1931 to Dec 2 1931) Tom Ashley; Clarence Greene; Gwen Foster; Walter Davis) Baby All Night Long; Bring Me A Leaf From The Sea; Drunk Man Blues; Cincinnati Breakdown; Corrina Corrina; Crooked Creek Blues; Far Across the Deep Blue Sea (Uniss); Goodnight Waltz; I Have No Loving Mother Now; Ham and Eggs (Uniss); Haunted Road Blues; Honeysuckle Rag; My Sweet Farm Girl; Nine Pound Hammer (Unissued); Penitentiary Bound; Short Life Of Trouble; There Will Come a Time (uniss); Washington and Lee Swing

The last recording sessions Ashley made until the 1960s were in NYC for Vocalion on Sept. 6-8, 1933, long after the Depression had forced cutbacks and layoffs.

Ashley & Foster; Vocalion Sept. 6-8, 1933: Ain’t No use To High Hat Me; Bay Rum Blues; Down At The Old Man’s House; East Virginia Blues; Faded Roses; Frankie Silvers; Go Way And Let Me Sleep; Greenback Dollar; Let Him Go God Bless Him; My North Carolina Home; Old Arm Chair; On Dark And Stormy Night; Rising Sun Blues; Sadie Ray; Sideline Blues; Time Ain’t Like They Used To Be;

A off-color blues, “My Sweet Farm Girl,” was also recorded at the 1931 Ashley and Foster session with the Blue Ridge Mountain Entertainers. When asked about the origin (it had already been recorded by the Ashley earlier-Carolina Tar Heels in 1930) Guthrie Meade said, “Tom Ashley heard this sung by a work gang around 1900.” In fact Clarence Williams, the black jazzman and bandleader issued this song for Columbia, 7/20/1928, as "Farm Hand Papa," and this is where Ashley got it. Williams accompanies himself on a very rockin' piano and throws in an occasional yodel. This illustrates the length Ashley and other pioneers of the recording industry would go to disguise the source of their songs; thus avoiding copyright infringement.

Ashley After The Depression

Although music was Ashley's life, he had many other occupations. He raised tobacco, raised cattle, hauled furniture, coal, and beans, and worked at sawmills. He was one of the best at ricking lumber for air-drying. The degree of perfection with which he ricked lumber often earned him a job when twenty others were waiting in line ahead of him. In 1943 Ashley gave up the medicine show circuit, bought a truck and worked with his son J.D. hauling furniture, coal and lumber.

In the early forties, times were better, and musicians began to return to their professions. Charlie Monroe hired Ashley as a black-faced comedian for the group known as "The Kentucky Pardners." It was with this group that Ashley met Tex Isley with whom he played again in the 1960's. In the late forties, Ashley injured the index finger of his right hand, and the finger became stiff. Thinking he could no longer play, he laid up his banjo and guitar although he still sang occasionally. He started teaching his songs to Clint Howard, who played guitar, and Fred Price, who played fiddle. He continued to attend fiddlers' conventions where he could once again see his "old cronies" and talk about music.

Ashley Is Rediscovered

Had it not been for a chance meeting with Ralph Rinzler at The Old Time Fiddlers' Convention at Union Grove, North Carolina, in 1960, perhaps thousands of people, who later thrilled to his banjo picking, singing and witticisms, would not have had that opportunity. Rinzler, a man devoted to traditional folk music, struck up a conversation with Ashley. Learning only that Tom was an Ashley, Rinzler asked if he knew a Clarence Ashley. Ashley said that he thought he had heard of him but was not quite sure. Rinzler talked about how much he liked the early recording of "The Coo-Coo Bird." He told about writing letters and sending telegrams to Clarence Ashley at Mountain City only to have them returned saying there was no such person. Ashley admitted his true identity, but he would not play an instrument at all and would sing only one song, "Put My Little Shoes Away."

After writing to Ashley and calling him many times, Rinzler and Eugene Earle came to Shouns in September of that year to record him. Ashley would not play, but he sang many songs, which were released on Folkways Records. Rinzler was able to convince Ashley of a sincere interest by the people in the cities in his kind of music. Ashley picked up his banjo once more, and a very active career followed in the next few years. Ashley and his friends appeared before large audiences in cities such as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, and they recorded two albums for Folkways.

The group that performed in the sixties included now world-famous Doc Watson of Deep Gap, North Carolina. Ashley's arrangement of "The Coo-Coo Bird," with Doc Watson on guitar and Ashley on the banjo, often left huge audiences completely hushed. In May of 1966, the highlights of Ashley's career came when he and Tex Isley, a talented guitarist from Reidsville, North Carolina, made a musical tour through England with eighteen engagements on the itinerary.

Ashley had been invited to go back to England the following summer and was planning to go, but he became sick and found that he had cancer. On June 2, 1967, four days before he was to go to England for the second tour, Ashley died. The life and career of one of the best traditional musicians was part of the past. Ashley was buried on his little hillside near his home, the place he requested to be buried and the subject of a song he wrote entitled "Little Hillside."

Ashley's songs brought together the mountain combination of the struggle for life and the romantic. He delivered his songs and "ballets" with the magic ingredient of personal involvement that the best singers own. Ashley preferred music that had feeling, and he named as his favorite performers Bill Monroe, Jimmy Rodgers, and Mahalia Jackson. Ashley said, "A lot of people in the city are playing old-time music these days. But country people play their feelings and feel their playing. That's the big difference."

Old Time Music At Clarence Ashley’s (Vol. 1- 1961 and Vol. 2-1963) with Tom Ashley, Doc Watson, Tommy Moore Clint Howard, Fred Price, Jack Johnson, Eva Ashley Moore, Jack Burchette, and one cut with Garley Foster: A Short Life Of Trouble; Amazing Grace; Banks Of The Ohio; Brown's Dream; Carroll County Blues; Chilly Winds (Lonesome Road Blues); Claude Allen; Cluck Old Hen; Coo-Coo Bird; Corrina, Corrina; Crawdad Song; Cumberland Gap; Daniel Prayed; East Tennessee Blues; Fire On The Mountain; Footprints In The Snow; Free Little Bird; God's Gonna Ease My Troublin' Mind; Handsome Molly; Haunted Woods; Humpbacked Mule; Honey Babe Blues; I Saw A Man At The Close Of Day; I'm Going Back To Jericho; John Henry; Lee Highway Blues; Little Sadie; Looking T'ward Heaven; Louisiana Earthquake; Maggie Walker Blues; My Homes Across The Blue Ridge Mountains; Old Man At The Mill; Old Ruben; Poor Omie (Omie Wise); Pretty Little Pink; Rambling Hobo; Richmond Blues; Rising Sun Blues; Run, Jimmie, Run; Sally Ann; Shady Grove; Shout Lulu; Sitting On Top Of The World; Skillet Good And Greasy; Sweet Heaven When I Die; Tough Luck; True Lovers; Walking Boss; Way Downtown; Wayfaring Pilgrim; Will The Circle Be Unbroken; Willie Moore