Daniel Wyatt Tate: Singer from Fancy Gap

by Michael Yates

Folk Music Journal, Vol. 4, No. 1 (1980), pp. 3-23

Daniel Wyatt Tate: Singer from Fancy Gap

by MICHAEL YATES

'I like music that's smooth, that counts out well, and has a pretty tune.'

Mrs. Julian of Knoxville April 14th, 1917.

To many people in Britain the term Appalachia is synonymous with the collecting work of Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles,who paid three visits to the Appalachian Mountain regions of North America in 1916, 1917 and 1918. During their trips Sharp and Karpeles spent a total of 46 weeks in five mountain states- North Carolina, Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee and West Virginia-where they managed to note some 1,612 tunes, representing about 500 different songs, from 281 singers.

Following his initial trip, Sharp and an American associate, Olive Dame Campbell, published 122 songs and ballads-with 323 tunes-under the title English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians (1917). A second, and greatly enlarged edition, appeared in 1932 under the editorship of Maud Karpeles, Sharp having died in 1924.

Even today Sharp is often thought responsible for the discovery of so-called English folksongs and music in the southern upland region of North America. In fact this is a misconception, and one that should have been apparent ever since the first edition of his book appeared. Of the 122 songs in the 1917 edition at least a quarter had been collected in Kentucky and Georgia by Olive Dame Campbell during the period 1907 to 1910. Other native collectors had also been at work. In 1889 James Mooney published a paper 'Folklore of the Carolina Mountains' in the Journal of American Folklore. Later Journal articles include 'Some Real American Music' by Emma Bell Miles (1904), 'Old-Country Ballads in Missouri' by Henry Belden (1906), 'Ballads and Rhymes from Kentucky' by George Kitteridge (1907), 'Folk-lore of the North Carolina M ountaineers' by Haywood Parker (1907) and 'Ballads and Songs of Western North C arolina' by Louise Rand Bascomb (1909). Two years later, in 1911, Hubert Gibson Shearin titled a paper that he contributed to the Swanee Review' British Ballads in the Cumberland Mountains'. Sharp, in company with previous native colour-writers-and, I suspect, heavily in fluenced by them-clearly saw the mountaineers as a separate body of people, distinct from those Americans that he had encountered in the northern cities, and I find it interesting to note how many subsequent collectors have been influenced by Sharp's beliefs. In the introduction to English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians Sharp writes,

'The present inhabitants. . are the direct descendants of the original settlers who were emigrants from England and, I suspect, the lowlands of Scotland ... Their speech is English, not American, and, from the number of expressions they use which have long been obsolete elsewhere, and the old-fashioned way in which they pronounce many of their words, it is clear that they are talking the language of a past day ... In their general characteristics they remind me of the English peasant, with whom my work in England for the past fifteen years or more has brought me into close contact'.

In his unpublished field notes he writes, 'really a piece of 18th century or 17th century England ... not so much a case of arrested development so much as arrested degeneracy'. When one considers how vague and innaccurate Sharp was in his notion of the 'English peasant' [2] then it becomes apparent that his Appalachian experiences were even more fanciful. Without doubt his romanticism is lacking i n historical perspective. It is, as I said, clearly based on the viewpoints of 19th century local colour-writers and, put bluntly, just does not stand up to any formol serious historical analysis.

Readers wishing to understand the complexities of mountain life following the civil war and reconstruction periods are advised to ignore Sharp's blinkered history- but not the songs that he so successfully collected- and rather consider some of the writers that I append at the end of this paper. I would especially recommend the works of Paul Gaston, Henry Shapiro and C. Vann Woodward.

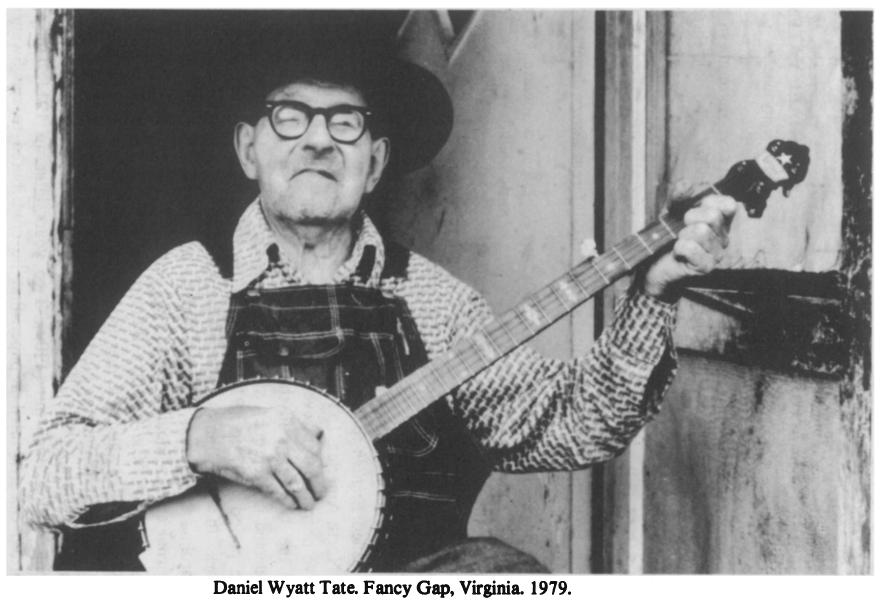

Dan Tate was born in Carroll County, Virginia in the year 1896. Today he lives in Fancy Gap, a few miles fromh is birthplace. Fancy Gap stands at an altitude of 3,000 feet and is some 15 miles to the north of Mount Airy, North Carolina. The Blue Ridge Parkway runs just to the south and the views across N orth Carolina, towards M ount Airy and Pilot Mountain, are truly spectacular. Dan lives off the Hillsville road. Route 775 winds into a low ridge of hills that rise to the Piper's Gap section. His house stands at the side of this road. He has spent most of his life living in this region of the Blue Ridge.

Life was undoubtedly hard for the settlers. During the 1918 influenza epidemic, when some 21 million Americans died, only Dan and his mother survived out of an immediate family of seven. He recalls that each fall prior to 1918 his father would walk down the mountain to Mount Airy carrying six home-made chairs on his back. These he would exchange for a winter's supply of flour, cornmeal, sugar and tobacco, all of which he would then carry the fourteen uphill miles home. In his diary entry for August 27th 1918 Cecil Sharp draws a vivid picture of what travel must have been like along the Virginia-North Carolina border,' to Meadows of Dan... in (a) Ford ... we must have gone up at least 2,000 feet-for our house we stay at is 3,480 feet up-over the worst and most dangerous mountain road I have ever seen. We cautiously got out and walked over especially bad patches. At one very bad corner, with a 700 foot fall on the left, (the driver) asked us to get out as he was afraid (the car) might topple over!'

Most of Dan's songs came to him from the singing of his sister Marguerite, a,lthough his 'frolic' songs-those short stanzas that act as mnemonics for fiddle and banjo tunes-were, to use Dan's own phrase, 'known to anyone who played a fiddle or picked a banjer'. Dan bought his first banjo in 1919 and learnt to play in the clawhammer style [3] from older neighbours who had been playing in this manner for several years. In English Folk Songs from the Southern Mountains Sharp wrote that only one singer sang to an instrumental accompaniment, the guitar; adding that this was in Charlottesville, Virginia, as if to imply that this was an urban corruption. Sharp further states that the only instrumental music heard were jig tunes played by two fiddlers; Michael Wallin of Allenstand, Madison County, North Carolina, and R euben Hensley of Carmen, Alleghany County, North Carolina. Their repertoire consisted of such tunes as 'Sourwood Mountain', 'Johnson Boys', 'CumberlandG ap' and 'High March'. On August 21st, 1918 Sharp noted a further three tunes from Charles Cannady of Endicott, Franklin County, Virginia. These were 'Round Town Girls', 'Sandy River Bell (sic)' and 'Shooting Creek'. Six days later Sharp visited the Blackett family of Meadows of Dan. Sharp's diary records the event thus 'After lunch and a short rest to the Blackett's and stay there a couple of hours. He sang me seven or eight fairly good songs and is a "banjer-man" while I played the piano-quite a nice one.' Sadly Sharp makes no further comment about Mr Blackett's banjo playing. Nor did he note any tunes.

Robert B. Winans [4] suggests that clawhammer banjo existed in Virginia in the 1880's. Other well-known Virginian banjo players, such as Hobert Smith of Saltville, Wade Ward of Independence and Glen Smith of Hillsville, state that they first heard clawhammer playing c. 1900-1904. [5]

The reader may ask precisely why this should be considered an important point. If one is to accept Sharp's findings that there was little, if any, instrumentaml usic in the mountains during the period 1916-1918, then, according to Sharp's argument, it follows that the mountaineers-and their song repertoire-were too isolated to be affected by outsidei nfluence. But, as I briefly said above, this was not the case. In the 1850's Minstrel Shows-the original source of the 5- string banjo that we know today-travelled by road and river throughout West Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky whilst in the 1860's, duringt he Civil War, many mountain soldiers travelled far from their homes, often encountering new musical forms. Can it be that Cecil Sharp, accustomed to an a cappella song tradition in southern E ngland, did not wish to hear singers with banjos or guitars? Can it be that the 'nigger banjer' clashed too harshly with his belief in a transplanted 17th century English peasantry?

Dan Tate first came to the notice of folklorists in 1941 [6] when Professor Fletcher Collins of Elon College, North Carolina, recorded him and Calvin Cole [7], another fine Fancy Gap singer and banjo player. One song from this period has been issued by the Library of Congress[8]. The speed of this performance, together with the inadequate recording machine, has previously made it difficul to fully transcribe the text of the song. The booklet accompanying the Library of Congress recording gives the following transcription:

Sally Brown

1 Old Sally, young Sally, cousin Sally Brown,

Hollow of her foot kept a-diggin' in the ground.

Ho, babe, and-a come on down.

Ho, boys, and you better get around.

Chorus: Swing old Adam and swing old Eve,

Swing once more before you leave.

2. Ho, babe, and-a come on down.

Ho, babe, and you better get around.

Chorus:

3. Swing old Adam and swing old Eve,

Swing once more before you leave. Ho, Babe!

On August 6th, 1979 I recorded Dan singing the following two stanzas. Stanza 1 corresponds with Professor Collins' untranscribed second stanza:

1. Walk in gentlemen, take a drink of gin,

You're just as near to heaven as you'll ever be again.

Walk in gentlemen, take a drink of grog,

Did you ever see a tadpole a-turn into a frog?

2 Saw a little nigger, he's a-coming out of town,

The hollow of his foot kept a-digging in the ground.

Soap, grease and butterheel come melting down the lane,

Black cloud a-rising, don't you think it's gonna rain?

It will clearly be seen that the above two stanzas are hardly connected textually, their only link being a common shared tune.[9] During a two week period I recorded some forty songs from Dan and was struck by the number of items that comprise elements and fragments from other songs. The same may be said for some of the songs that I recorded from other singers in the region. Obviously songs that concern an emotion, say a broken romance, need little narrative and can easily be constructed using so-called 'floating' verses. Dan's version of the song 'Lonesome Dove' is constructed in this manner:

Lonesome Dove

1. Look up, look down that lonesome road,

Hang down your head and cry.

If I knew my true love was false to me

I would take morphine and die.

2. Oh don't you see that lonesome dove,

It's flying from pine to pine.

It's mourning for it's lost true love

Like I would mourn for mine.

3 I'm going away, the Lord knows where,

Away to Tennessee.

For I have no place to lay my head

But on my true love's knee.

4 Repeat stanza 1.

This does not, however, explain the origin of such songs as 'The Waggoner's Boy' that Dan sings:

The Waggoner's Boy

1 Oh I won't be a waggoner's boy,

And I won't work on the farm.

I'd rather stay in my poppa's house

And lay in a pretty girl's arms.

2 Can't come in and I won't come in,

For I haven't got a moment's time.

Heard you had a new sweetheart

And you're no longer mine.

3 Oh if I had a pig in a pen,

Corn to feed it on,

All I'd want is a pretty little girl,

To feed it when I'm gone.

All three stanzas have appeared elsewhere in separate and distinct songs. For example, stanza 1 would appear to be related to the song 'Roll in my Sweet Baby's Arms': [10]

Ain't gonna work on the railroad,

Ain't gonna work on the farm.

Lay 'round the shack' till the mailtrain co mes b ack,

Then I'll roll in my sweet baby's arms.

Stanza 2 shows marked similarities to an 'answer' stanza in the ballad of 'Young Hunting' (Child 68):

I can't come in, I won't come in

And stay this night with thee,

For I have a wife in Old Scotchee

This night a-looking for me.

Stanza 3 occurs as an opening stanza in the fiddle and banjo tune 'Pig in a Pen''.[12] One purpose of my stay with Dan was to re-record songs that had previously been noted by George Foss in 1962 in order to consider any changes that may have occurred over a period of time. Possibly the most interesting textual comparison can be seen in Dan's version of 'The Two Sisters' (Child 10), which he calls 'The Dreadful Wind and Rain'. Text A, recordedo n July 10th, 1962, can be heard on the Blue Ridge I nstitute record listed at the end of this paper. Text B was recorded by me on August 6th, 1979 and a copy is held in the Vaughan W illiams Memorial Library at Cecil Sharp House.

The Dreadful Wind and Rain- Text A

1 Two loving sisters was a-walking side by side,

Oh, the wind and rain.

One pushed the other off in the waters, waters deep,

And she cried, 'A dreadful wind and rain'.

2 She swum down, down to the miller's pond,

Oh' the wind and rain.

She swum down, down to the miller's miller's pond,

And she cried, 'A dreadful wind and rain'.

3 Out run the miller with his long hook and line,

Oh, the wind and rain.

Out run the miller with his long hook and line,

And he cried, 'A dreadful wind and rain'.

4 He hooked her up by the tail of the gown,

Oh, the wind and rain.

He hooked her up by the tail of the gown,

And he cried, 'A dreadful wind and rain'.

5 They made fiddle strings of her long black hair,

Oh, the wind and rain.

They made fiddle strings of her long black hair,

and she cried, 'A dreadful wind and rain'.

6 They made fiddle screws of her long finger bones,

Oh, the wind and rain.

They m ade fiddle screws of her long finger bones,

And she cried,' A dreadful wind and rain'.

7 The only tune that my fiddle would play,

Was, Oh, the wind and rain.

The only tune that my fiddle would play,

And he cried, h e cried, a dreadful wind a nd r ain.

The Dreadful Wind and Rain- Text B

1 Two loving s isters was a-walking side by side,

Oh, the wind and rain.

One pushed the other off in the waters deep,

And she cried,' The dreadful wind and rain'.

2 She swam on down to the miller's pond,

Oh the wind and rain.

She swam on down to the miller's pond,

And she cried,' The dreadful wind and rain'.

3 Out ran the miller with his long hook and l ine,

Oh, the wind and rain.

He hooked her up by the tail of her gown,

And he cried,' The dreadful wind and rain'.

4 Well he made fiddle strings of her long black hair,

Oh, the wind and rain.

They made fiddles trings of her long black hair,

And he cried, 'The dreadful wind and rain'.

5 They made fiddle screws of her long finger bones,

Oh, the wind and rain.

They made fiddles crews of her long finger bones,

And he cried,' The dreadful wind and rain'.

6 Well the only tune that my fiddle would play,

Was, Oh, the wind and rain.

The only tune that my fiddle would play,

Was, he cried,' The dreadful wind and rain'.

Maud Karpeles returned to the Appalachian M ountains in the early 1950's. She was later to write, 'The region is no longer the folk-song collectors paradise, for the serpent, in the form of the radio, has crept in, bearing it's insidious hill-billy and other "pop" songs.[13] No longer the folk-song collectors paradise? It is, I suppose, yet again a question of definition. Possibly the British ballads have declined, but in their place we find much that is exciting and vital. I have selected the following songs from Dan Tate's repertoire to try to give some indication of those songs that I found beings ung in the Appalachian Mountains today. I should like to thank him. His generosity and friendship will be long remembered.

BUGERBOO

1 Come all you jolly boatsman boys,

Who want to learn my trade.

The very first wrong I ever done

Was courting of a maid.

2 I courted her the winter's night,

And a summer season too.

And when I gained her free good will

I knew not what to do.

3 Last night I lay in a fine feather bed

With the squire and a baby.

Tonight I'll lay in a barn of hay

In the arms of Egyptian Daisy.

4 Wake up, wake up, my pretty little miss.

Wake up, for day has come.

Wake up, wake up, my pretty little miss

For the bugerboo has gone.

5 Yes I went to see this little girl,

I loved her as my life.

I took this girl and I married her

And she made me a virtuous wife.

6 But I never tell her of her faults,

And dog me if I do,

But every time the baby cries

I think of the bugerboo.

For a full description of this song see Professor Thomson's article 'The Fearful Foggy Dew' in this Journal. Stanza 3 is a 'stray' from 'The Gypsy Laddie (Child 200). Dan's comment to me that the boatman 'must have been a Lord or something' suggests that the stanza was present when Dan first heard the song.

FISH ON A HOOK

1 Fish on a hook, fish on a line,

Fish no more 'til the summer time.

2 Throw my hook to the middle of the pond,

Fish for the girl with the josy on.

3 Repeat stanza 1

4 See that catfish a-going upstream,

What in Hell does a catfish mean?

5 Fish that catfish by it's snout,

Turn that catfish wrong side out.

6 Repeat stanza I

Stanzas 4 and 5 appear in Brown vol. 3, pp. 220-21. JAFL vol. xliv, p.436, vol. xlix p.235. Scarborough p. 1 99 and Sharp vol. 2, p.36 1.

GET ALONG HOME CINDY

1 Railroad, a plank road,

River and canal.

If it hadn't have been for Doctor Grey,

There never would have been any Hell.

Chorus: Get along home Cindy,

Get along home I say.

Get along home Cindy girl

For I am going away.

2 A railroad, a plankroad,

A river and canoe.

If it hadn't have been for old John Jones,

They never would have killed old Jude.

'Jude became pregnant. She was a slave. She was one of Doctor Grey's slaves and they tried to make her tell who the father of the child was. And she wouldn't tell, so they said they'd make her tell. Well, they beat her as long as they could and old John Jones must have helped them out in beating that lady to death. Well, she crawled to the stream of water to drink, and died. That's the way that slaves was treated by peoplei n this country. She told them she wouldn't tell them who the father of the child was. She told them it was a white man and a gentleman.'

To my knowledge this is a unique version of the well-known song 'Cindy'. I am unable to say if the story is based on fact, although Dan believes it to be true. For a standard version see Lomax p. 233.

GROUNDHOG

1 Hunt up your guns and call up your dogs (x2)

Go to the mountain and catch a big groundhog.

Groundhog.

2 We've turned it over and we've skinned one side (x2)

Hell-fire girls ain't a groundhog wide.

Groundhog.

3 Meat in the cupboard and hide in the churn( x2)

If that ain't groundhog I'll b e durned.

Groundhog.

4 Yonder comes Granny with a snigger and a grin (x2)

Groundhog gravy all over her chin.

Groundhog.

5 Yonder comes Granny with her two canes (x2)

She swore she'd eat them groundhog brains.

Groundhog.

It was a pleasure to drive along the Blue Ridge Parkway in the early morning watching the groundhogs playing along the roadside. Other versions appear in Brown vol. 3, pp. 253-55 and Lomax p. 251. Recordingisn clude Frank Proffit of North Carolina (Folkways FA2360), Doc Watson also of North Carolina (Folkways Fa2366) and Vester Jones of Virginia (Folkways FS3811).

LITTLE FISHERMAN

1 Hey my little fisherman I wish you mighty well (x2)

Have you any sea crabs here for to sell?

Chorus: To my wack, to my foddle and ca-divy.

2 Yes sir, yes sir, I've one, two, three (x2)

And the best one of them I'll sell to thee.

3 He picked it up all by the backbone (x2)

He throwed it 'cross his withers and he wagged off home.

4 Well the old man he got home. for the want of a dish (x2)

He threw it in the pot where the women went to piss.

5 Well the old man got up to piss as you might suppose (x2)

Wack went the sea crab and caught him by the nose.

6 John for the flesh fork and Sally for the ladle (x2)

And they beat the old man clean off to the navel.

For a Kentucky version see Cray p.3-4. The tune is a variant of that used for the song 'Groundhog'.

MOLLY VAN

1 Come all you young men who handle a gun,

Beware of your shooting just after set sun.

2 Jimmy Randal was a-hunting, it was all in the dark,

He shot at his sweetheart and he missed not his mark.

3 Stooped under a beech tree the shower to shun,

With her apron pinned around her, he shot her for a swan.

4 Jimmy Randal was a hunting and the night was coming on.

With her apron pinned around her he shot her for a swan.

5 Jimmy Randal went home with his gun in his hand,

Saying, 'Mother, dear Mother, I have shot Molly Van'.

6 Yes I've killed this fair maiden and I've taken her life,

And I always intended to have made her my wife'.

7 Come all you young women and stand you in a row,

Molly Vanders in the middle as a mountain of snow.

For American versions see Brown vol. 2, p.263, Cox p.339, Eddy p.194, Gardner p.66, Hudsonp. 145, Sharp vol. 2, p.328.

MUCK ON MY HEEL

1 I looked at the sun

And the sun it looked high.

I looked at my boss

And my boss he looked shy.

Chorus: So it's muck on my heel,

Muck on my toe.

There's a muck so hard

That my shovel won't go.

2 I asked my boss,

And he said I might

Go see my girl

Next payday night.

For a negro text, 'Mule Skinner's Song', see Scarborough p.230.

NIGGER AND A MULE

1 Oh I don't like a nigger no how.

No I don't like a nigger no how.

For a nigger and a mule, they're a railroad tool.

So I don't like a nigger no how.

2 I don't like a poor white man.

No I don't like a poor white man.

He has a head like a hoss, and he wants to be the boss,

So I don't like a poor white man.

3 Repeat stanza 1

4 Oh where have you been so long?

Oh where have you been so long?

I have been out on the bend with those rough and rowdy men,

And I'm nothing but a nigger when I'm gone

The only other printed version of this song would appear to be that collected by the poet Carl Sandburg from a Kentucky mountain source, 'I Don't Like No Railroad Man' in Sandburg p.326, and I would suspect that Sandburg's text has been edited to remove the term 'nigger'. Stanza 4 also appears in Dan's version of the song 'Mole in the Ground'.

OLD GREY GOOSE

1 Johnny Gordon lost his cow

And where do you reckon he found her?

Found her up that rocky branch

Witha hundred buzzards round her.

Chorus: Look here, look there,

Look away over yander.

Don't you see that old grey goose

A-smiling at that gander?

2 Johnny Gordon lost his wife

And where do you reckon he found her?

He found her up that rocky branch

With a hundred men around her.

Another song that I have been unable to trace in other collections. The tune does not appear to be related to the Kentucky fiddle tune 'Old blue Goose'.

OLD MISTER RABBIT

1 Oh, what you gonna do when your meat gives out, baby? (x2)

Sit in the corner with your mouth stuck out, babe.

2 What you gonna do when it comes a-snow, baby? (x2)

Catch those rabbits as they go, babe.

3 Catching rabbits ain't no sin, baby (x2)

Turn them loose then catch 'em again, babe.

4 Old Mister Rabbit a-sitting by a log (x2)

Yes, by jove I'm a-watching for a dog, babe.

5 Old Mister Rabbit your ears is mighty thin, baby (x2)

Yes, by jove I split the wind, babe.

6 Old Mister Rabbit your tail is mighty white, baby (x2)

Yes, by George I'm sitting out of sight, babe.

7 Old Mister Rabbit your eyes are might red, baby (x)

Yes, by George I'm darn nigh dead, babe.

Versions of this song have appeared in collections from all over the South, often from negro singers. A version appears in Joel Chandler Harris' 'Uncle Remus, His Songs and Sayings', 1928 edition. For other versions see Brown vol. 3 pp.211-13. JAFL vol. xxiii pp.435-36, vol. xxiv p.317 and 356, vol. xxvi p.132, vol. xli p.573. Scarborough pp.17 3-75. The late Horton Barker of Virginia sang an especially fine version (Folkways FA2362).

OLD TRUE LOVE

1 I went a -roving on one cold winter's night,

A-drinking of sweet wine;

When I fell in love with this pretty little miss

She stole this heart of mine.

2 Now she looked like some pink or some rose

That blossomed in the month of June.

Or some sweet musical instrument

That's newly put in tune.

3 Oh I wish to the Lord I had never been born,

Or died when I was young;

So I never could have kissed your sweet ruby lips

Nor heard your lying tongue.

4 Now I'll put my foot in the bottom of a ship,

I'll sail it on the sea.

I would not have treated you my love

Like you have treated me.

5 Now who will shoe your pretty little feet?

And who will glove your hand?

And who will kiss your sweet ruby lips

When I'm in some far-off land?

6 Papa will shoe my pretty little feet,

And Mama will glove my hand;

And you will kiss my sweet ruby lips

When returned from a far-off land.

7 And the blackest crow that ever flew

It surely will turn white.

Whenever I prove false to you

Bright day will turn to night.

8 And the time rolls on when the seas shall run dry,

And the rocks melt down by the sun.

I never will prove false to you

Till all this work is done.

This is clearly one of Dan's finest songs; and one that contains elements from several other pieces. As 'The True Lover's Farewell' see Arnold p.14, Brewster p.348, Brown vol. 3 pp.299-304 and Sharp vol. 2 pp.113-18.

RABBITS IN THE BOTTOM

1 Oh the rabbits in the bottom,

Kicking up the sand.

Take my girl to shoot them,

Fry 'em in my pan, fry 'em in my pan.

Chorus: Shoot a rabbit down,

Shoot a little rabbit down.

2 Oh when you see that girl of mine,

Oh tell her if you please;

Before she goes to make up dough

Roll up them dirty sleeves, roll up them dirty sleeves.

3 Oh when you see that girl of mine,

Don't you fail to tell her;

Not to fool her time with me

But to hunt some other fella, but to hunt some other fella.

A favourites ong in the area around Fancy Gap. Stanza 2 appears in Galax-a few miles to the west (Folkways FS3832) and the tune is known in the Mount Airy district to the south (County7 01).

ROUSTABOUT

1 Roustabout, my bare footed child,

Take your boat to the shore.

There's a hundred dollar bill

And I've got no change,

So don't you want to go?

2 Walkabout, on Sunday my boys,

What pleasure can I see?

When I've got a woman in New Orleans

And she won't write to me.

3 So roustabout, my barefooted bums,

Take your boat to the shore.

There's a hundred pretty women

On the other side,

Oh don't you want to go?

This would appear to be related to the 'RoustaboutH oller't hat was recorded in 1939 by John Lomax from a Texas singer, Henry Truvillion (AAFS recording 2 658-unissued). The North Carolina singer and musician Fred Cockerham has also recorded a somewhat similar piece (County 717).

THE SAILOR'S SONG

1 Oh the first on deck was the Captain of the ship,

Fine young Captain was he.

He formed a song, 'We've all done wrong'

As we sailed on the lonesome sea.

Chorus: Stormy winds let them blow,

Raging seas let them roar.

While these poor sailors all a-running up the ropes

And the landlord a -crying out below.

2 Well the next on deck was the lady of the ship,

Fine young lady was she.

She formed a song, 'We've all done wrong'

As we sailed on the lonesome sea.

3 The next on deck was the doctor of the ship,

A fine young doctor was he.

He told his patients on their beds so low

They would sink to the bottom of the sea.

4 Well the next o n deck was the drunkard of the ship,

A wicked old cuss was he.

He said he didn't give a damn if the boat would never land,

Let her sink to the bottom of the sea.

Child 289. Several American versions are to be found in volume 4 of Bronson. Of special interest is the version recorded commercially by Ernest V. Stoneman of Galax, Virginia in 1928 and issued on Victor 21648 (Bronson vol. 4 p.378). S toneman's song has also been reissued on Rounder 1008.

Bibliography to song notes:

Byron Arnold, Folksongs of Alabama (Birmingham. 1950).

Paul G . Brewster, Ballads and Songs of Indiana( Bloomington, 1940).

Bertrand Bronson, The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads 4 volumes (Princeton, 1959-72).

The Frank Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore ed. Newman Ivey White, Paul F. Baum, et al., 7 volumes (Durham, 1952-64).

John Harrington Cox, Folk-Songs of the South (Cambridge, 1925).

Ed Cray, Bawdy Ballads (London, 1970).

Mary O 'Eddy, Ballads a nd Songs from O hio (New York, 1939).

Emelyn Elizabeth Gardiner & Geraldine Jencks Chickering, Ballads and Songs of Southern Michigan (Ann Arbour, 1939).

Arthur Palmer Hudson, Folksongs of Mississippi and Their Background (Chapel H ill, 1936).

Journal of American F olklore (1888-in progress).

Alan Lomax, The Folk Songs of North America (New York, 1960).

Carl Sandburg, The American Songbag ( New York,1 927).

Dorothy Scarborough, On the Trail of Negro Folk-Song (Cambridge, 1925).

Cecil J. Sharp, English Folk-Songs from the Southern Appalachians ed. Maud Karpeles. 2 volumes( London, 1932).

Bibliography and Discography relating to Dan Tate

Bertrand Bronson, The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads vol. iii (Harvard, 1966), 481 & 490. Vol. iv (Harvard, 1972), 118-19.

George Foss, 'More on a Unique a nd Anomalous Version of "The Two Sisters" in Southern Folklore Quarterly vol. xxviii N o. 2 (June, 1964), 119-33.

Dan Tate, 'Barbara A llen' and 'Wind and Rain' on Ballads from British Traditions (Blue Ridge Institute Records 002), 1978.

Dan Tate, 'Old True Love' on Clawhammer Banjo vol.3 (County 757), 1978.

Dan Tate, 'Old Sally Brown'-with Calvin Cole-on Play and Dance Songs and Tunes ( Library of Congress AAFS L9).

Charles E. Wray,' Mountain T reasures-Dan Tate' in The Carroll News (Hillsville, Virginia), January 11t h, 1979, 4.

Books relating to 'the New South' that have been useful in preparing this essay.

Dwight Billings, Planters and the Making of a 'New South': Class, Polities, and Development in North Carolina, 1865-1900( Chapel Hill, 1979).

Andrew Buni, The Negro in Virginia Politics, 1902-1965 (Charlottesville, 1967).

Paul M. Gaston, 'The "New South"', in Arthur S. Link and Rembert W. Patrick, eds., Writing Southern History(Baton R ouge,1965), 316-36.

Paul M. Gaston, The New South Creed: A Study in Southern Mythmaking (N ew York, 1970).

Jay Mandle, The Southern Plantation Economy after the Civil War (Durham, 1978).

Allen W. Moger, Virginia: Bourbonism to Byrd, 1870-1925 (Charlottesville, 1968).

Raymond H. Pulley, Old Virginia Restored: An Interpretation of the Progressive Impulse, 1870-1934 (Charlottesville, 1968).

Henry D. Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Conciousness; 18 70-1920 (Chapel Hill, 1978).

Harold Woodman, 'Sequel to Slavery: The New History Views in the Postbellum South', Journal of Southern History, 43 (1977), 523-55.

C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South, 1877-1913 (Baton Rouge, 1971).

C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (3rd ed., New York, 1974).

The following additional songs were also recorded from Dan Tate by Michael Yates:

Claude Allen (Laws E6) Old Dan Tucker

Cluck Old Hen Old Molly Judy

The Cuckoo Old Molly Row

Down the Road Once I Lived in Old Virginia

The Devil's Grandmother Poor Ellen Smith (Laws F 1 1)

Florella (Laws F 1) Pretty Mohee (Laws H8)

The House Carpenter (Child 243) Sally Ann

It Rained a Mist (Child 155) Skinner-My-Dinky-Di-Do

John Hardy (Laws I2) Sugar Hill

The Knife in the Window Walk Jawbone

Little Maggie Waves of the Ocean (Laws K 17)

Lord Ullin's Daughter Who's On the Way?

My Horses Ain't Hungry

Muck on my Heel, p.16. Since writing the above I have found that Dan's text is related to 'Roll on Buddy' as sung by Aunt Molly Jackson on the Library of Congress album L6 1 Railroad Songs and Ballads.

FOOTNOTES

1. Cecil Sharp field notes in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, EFDSS, 2 Regents Park Road, London NW 17AY.

2. See, for example, David Harker, 'Cecil Sharp in Somerset: Some Conclusions' in Folk Music Journal vol. 2 No. 3 pp. 220-40.

3. The so-called 'clawhammer' style of playing the banjo involves a downward picking with the right hand, so that the strings are played with the fingernails. The fingers of the right hand are bent like a claw. Numerous variations are used by traditional banjo players in the mountains.

4. Robert B. Winans, 'The Folk, the Stage, and the five-string Banjo in the Nineteenth Century' in Journal of American Folklore vol. 89 No. 354 (October/December1,9 76) pp. 407-37. Readers a re also referred to Gene Bluestein, 'America's Folk Instrument: Notes on the Five-String Banjo' in Western Folklore vol. xxiii No. 4 (October, 1964), pp. 241-48.

5 Winans pp. 424-25.

6 Dan insists that the Library of Congress recordings were m ade i n 1938. As Dan's memory appears to be accurate with other dates it may be that Professor Collins deposited his recordings with the Library in 1941.

7 Other recordings of Calvin Cole may be heard on the record' Old Originals' (Rounder Records 0058).

8 AAFS L9 'Folk Music-of the United States: Play and Dance Songs and Tunes' Edited by B. A. Botkin.

9 A variant of this tune was recorded in the 1920's by the Skillet Lickers as 'Ride Old Buck to Water'. This has been re-issued on 'The Skillet Lickers Vol. 2' (County 526).

10 'Roll in my Sweet Baby's Arms' was recorded on June 26th, 1931 by Buster Carter and Preston Young (Columbia1 5690-D).

11. Cecil Sharp, English Folk Songs from the Southern A ppalachians (London, 1932) Vol. 1, p. 101.

12 For a version, see Musicfrom South Turkey Creek (Rounder Records 0065).

13 Cecil Sharp: His Life and Work. New edition, edited by Maud Karpeles, 1967, p.170.