The Career of "John Henry"

by Richard M. Dorson

Western Folklore, Vol. 24, No. 3 (Jul., 1965), pp. 155-163

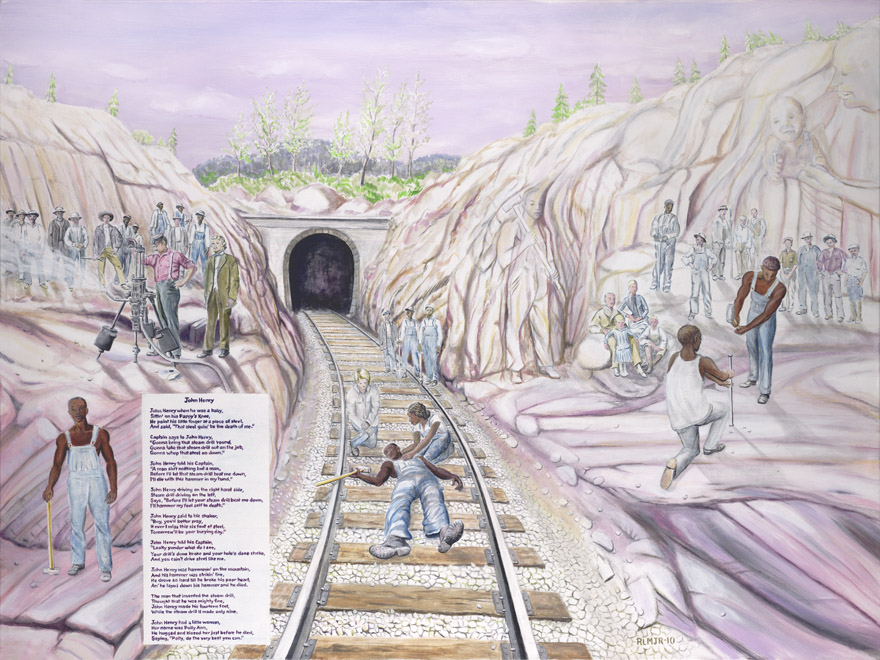

Painting by Richard L. Matteson Jr.

The Career of "John Henry"

RICHARD M. DORSON

FOR THIRTY-SEVEN YEARS after the completion of the Big Bend Tunnel in West Virginia, where John Henry presumably defeated the steam drill, his ballad escaped attention. Then in 1909 it received a short and cryptic note in the pages of the Journal of American Folklore. A collector of folk songs from the North Carolina mountains, Louise Rand Bascom, coveted a ballad on "Johnie Henry," of which she possessed only the first two lines.

Johnie Henry was a hard-workin' man,

He died with his hammer in his hand.

Her informant declared the ballad to be sad, tearful and sweet, and hoped to secure the rest "when Tobe sees Tom, an' gits him to larn him what he ain't forgot of hit from Muck's pickin'." [1] Apparently, Tobe never did see Tom, but the key stanza was enough to guide other collectors. In the next decade, five contributors to the Journal expanded knowledge of the work song and the ballad carrying the name of John Henry.

In 1913 the pioneer collector of Southern folk rhymes and folk songs, E. C. Perrow, printed four snatches of the hammer song and the first full ballad text, though from a manuscript. Perrow noted that workmen on southern railroads knew a considerable

body of verse about the famous steel-driving man, John Henry.[2] An as yet little-known collector, John Lomax, printed a splendid text of eleven stanzas in 1915, saying this was the ballad sung along the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad in Kentucky and West Virginia, but he provided no source at all, nor the tune.[3]

The next year, W. A. McCorkle, governor of West Virginia from 1893 to 1897, published an article in the Journal mixing John Henry with John Hardy, a Negro desperado hung in West Virginia in 1894. His view was followed by the folk song collector John H. Cox in the Journal in 1919 and again in his standard collection of 1925, Folk-Songs of the South, in which he mingled ballad texts of the two Negroes.[4] However the confusion between the two folk song characters became apparent to Newman I. White, who separated their texts in his American Negro Folk-Songs of 1928.[5]

Meanwhile two scholars had dedicated themselves to the task of recovering and weighing every last scrap of evidence surrounding John Henry. A professor of sociology at the University of North Carolina, Guy B. Johnson, included a chapter of texts on "John Henry, Epic of the Negro Workingman," in Negro Workaday Songs, a collection he made in 1926 with Howard W.

Odum.[6] At this time Johnson believed the song hero to be a "myth," but he changed his mind during the next three years and ended up accepting Big Bend Tunnel as the factual basis for the ballad. Johnson interviewed many Negroes and advertised his quest in Negro newspapers in five states, even staging John Henry contests to secure song texts and information. The resulting

harvest of letters and statements revealed a pervasive and widespread tradition, deeply enough rooted to manifest all the vagaries and inconsistencies of popular legend. Nearly every state in the south, and several in the north, claimed John Henry as their offspring. One particularly circumstantial account placed the steam drill contest in Alabama in 1882-but no documentary support could be found. However, struck by the relative stability of the ballad as compared with the fluctuations in narrative accounts, Johnson searched for and uncovered a printed broadside by one W. T. Blankenship, undated, which presumably both drew upon and contributed to the singing of the ballad. Johnson presented his book-length study in 1929-John Henry, Tracking

Down a Negro Legend.[7]

Coincidentally, a second sleuth had been pursuing John Henry, and trailed him to Big Bend Tunnel before Johnson. Louis W. Chappell, an associate professor of English in West Virginia University, published John Henry, A Folklore Study in 1933.[8] It took the form of a minutely detailed critique of Johnson's methods and interpretation, mainly because they preceded, and

derived from, his own. Chappell accused Johnson of using without acknowledgement a preliminary report he had made in 1925 on his findings at Big Bend Tunnel. The evidence painstakingly gathered and skillfully evaluated by Chappell builds a powerful case for the historicity of John Henry at Big Bend.9

With Chappell's exhaustive monograph, the scholarly probe into John Henry virtually ceased, and the two main questions-the relationship of John Henry to John Hardy and the factual basis for the steam-drilling contestwere laid to rest. Popular interest in the Negro hero, however, continued to grow.

Already, in his inquiry into the John Henry tradition, Guy B. Johnson had anticipated its potentialities for the creative arts. "I marvel" (he wrote) "that some of the 'new' Negroes with an artistic bent do not exploit the wealth of John Henry lore. Here is material for an epic poem, for a play, for an opera, for a Negro symphony. What more tragic theme than the theme of John

Henry's martyrdom?" [10] A response was not long in coming. Within two years, a book-length story of John Henry had been published and distributed by the Literary Guild. Its author, Roark Bradford, while not a "new Negro," had grown up on a Southern plantation near the Mississippi River and seen Negroes closely. Exploring Southern Negro culture for literary themes, he struck a profitable formula with fictional works depicting the childlike Negro conception of the world based on Scripture. Bradford achieved his greatest success with 01' Man Adam an' His Chillun (1928), rendered by Marc Connolly into the Broadway hit, The Green Pastures. The revelation of a tragic Negro folk legend seemed timed to assist his literary career. In Bradford's John Henry, the contest with the machine occupies only 5 out of 223 pages, but it serves as the dramatic climax for such structure as the book possesses. A cottonrolling steam winch on the levee replaces the rock-boring steam drill, and New

Orleans and the Mississippi River form the locale. John Henry is a cottonloading roustabout, when he is working; much of the time he is loving and leaving his girl Julie Anne, who follows him into death after his fatal contest with the new machine. At other times, he performs great feats of lifting, eating, and brawling. The whole narrative is written in a repetitious, rhythmic stage dialect, interspersed with plaintive little songs and centering around Negro literary stereotypes. The sporting man, the hell-busting preacher, the woman of easy acquaintance, the old conjure mammy are all present. John Henry is a new stereotype for the Negro gallery, but a well-established one in American lore-the frontier boaster-and he reiterates his tall-tale outcries on nearly every page.

In 1939 an adaptation of John Henry, billed as a play with music, appeared on the Broadway stage. Co-author with Roark Bradford was Jacques Wolfe, [Norman, Okla.: 1930]), "Steel-Drivin' Man," pp. 413-415). Gordon H. Gerould in his wellknown

study, The Ballad of Tradition (Oxford, 1932), pp. 264-268, discussed the confusion of "John Henry" with "John Hardy," speculated that "John Henry" was of Negro origin, and reprinted a 22-stanza text from Johnson, pp. 289-292. Louise Pound lauded Johnson's John Henry in her review in the Journal of American Folklore, XLIII (1930), 126-127. who supplied the musical scores for the song numbers. The play followed closely the original story, which contained obvious elements for a musical

drama. Paul Robeson starred as John Henry. The Broadway production closed after a short run."

The book and the play of Roark Bradford, with attendant newspaper reviews and magazine articles,[12] popularized the name of John Henry, and fixed him in the public mind as a Negro Paul Bunyan. In many ways, the growth of the John Henry legend and pseudolegend parallels that of the giant logger, who was well established as a national property by the 1930's. Bradford's John Henry resembles James Stevens' Paul Bunyan of 1925 as a fictional portrayal of an American "folk" hero based on a slender thread of oral tradition-in one case a few northwoods anecdotes, in the other a single ballad. Bradford, like Stevens, created the picture of a giant strong man, although with a somber rather than a rollicking men, as befit a Negro hero. In 1926 Odum and Johnson called John Henry the "black Paul Bunyan of the Negro workingman." Carl Sandburg made the comparison the following year in The American Songbag, saying both heroes were myths. Newspapers referred to John Henry as the "Paul Bunyan of Negroes," "the Paul Bunyan of his race, a gigantic river roustabout whose Herculean feats of work and living are part of America's folklore." [13]

In the later history of the two traditions, the parallelism persists. Writers, poets, and artists attempted to wrest some deeper meaning from the Paul Bunyan and John Henry legends and failed. But both figures lived on triumphantly in children's books of American folk heroes and in popular treasuries of American folklore.

The first presentation of John Henry as a folk hero came in 1930 in a chapter of Here's Audacity! American Legendary Heroes, by Frank Shay, who had published books of drinking songs. His account of "John Henry, the Steel Driving Man," followed Guy B. Johnson's preliminary essay of 1927 on "John Henry: A Negro Legend." [14] Shay's formula was repeated by a number of other writers for the juvenile market, all of whom inevitably included the story of John Henry and his contest with the steam drill in their pantheon of American comic demigods. Such folk-hero books were written by Carl Carmer (1937), Olive Beaupr6 Miller (1939), Anne Malcolmson (1941), Carmer again (1942), Walter Blair (1944), and Maria Leach (1958).[15]

Other authors of children's books found it rewarding to deal individually and serially with Paul Bunyan and his kin. Consequences were John Henry, the Rambling Black Ulysses, by James Cloyd Bowman (1942), John Henry and the Double-Jointed Steam Drill by Irwin Shapiro (1945), and John Henry and His Hammer, by Harold W. Felton (1950). Of these, Bowman's nearly three hundred pages went far beyond the ballad story to give a full-length improvisation of John Henry's career, from a slave boy on the old plantation through the Civil War to freedom times.

John Henry encourages unruly

freedmen to mine coal, cut corn, pick cotton, and drive railroad ties. He outsmarts

confidence men and gamblers, stokes the Robert E. Lee to victory over

the Natchez, and at long last dies with his hammer in his hand at the Big Bend

Tunnel. But a final chapter presents an alternate report, that John Henry

recovered from overwork and resumed his ramblin' around. In Shapiro's much

briefer story, John Henry never dies at all, but after beating the steam drill

pines away to a ghost, until his old pal John Hardy convinces him that he

should learn to use the machine he conquered, and the tale ends with John

Henry drilling through the mountain, and the steam drill shivering to pieces

in his hands! So for American children John Henry unites the Negroes in

faithful service to their white employers and accepts the machine. In these children's books, the full-page illustrations of a sad-faced Negro giant swinging a hammer contributed as much as the printed words to fixing the image of John Henry.[16] In the 1930's, Palmer Hayden completed twelve oil paintings, now hanging in the Harmon Foundation in New York, on the life story of John Henry.[17]

Folklore treasuries and folk song collections also continued to keep the story and song steadily before the public. In his best-selling A Treasury of American Folklore (1944), currently in its twenty-third printing, B. A. Botkin reprinted accounts of John Henry in oral hearsay, balladry, and fiction; he gave him further notice in A Treasury of Southern Folklore (1949) and A Treasury of Railroad Folklore, done with Alvin C. Harlow (1953).[18] The lavishly illustrated Life Treasury of American Folklore (1961) offered a picture of John Henry spiking ties on a railroad track rather than driving steel in a tunnel, and in a skimpy headnote to the retelling of the ballad story revived the discredited hypothesis that the contest might have occurred in Alabama in 1882.[19]

John A. and Alan Lomax, naturally sympathetic to the ballad hero first presented in a full text by the elder Lomax in 1915, always included John Henry ballads, some adapted and arranged, some recorded in the field, in their popular folk song compilations: American Ballads and Folksongs (1934), Our Singing Country (1941), Folksong U.S.A. (1947), and The Folksongs of North America (1960). "John Henry" was the opening song in their first book, and in Our Singing Country they called it "probably America's greatest single piece of folklore." In the latest and most ornate garland, Alan Lomax (the

sole author), having meanwhile shifted from a Marxian to a Freudian analysis,

found John Henry equally receptive to his altered insights. The steel-driver

shaking the mountain is a phallic image; singers know that John Henry died

from lovemaking, not overwork:

This old hammer-WHAM!

Killed John Henry-WHAM!

Can't kill me-WHAM!

Can't kill me-WHAM!

Thus the hammer song vaunted the sexual virility of the pounder.[20] Lomax had returned full cycle to the psychoanalytic views of Chappell. The steeldriver also appealed to social reformers. In American Folk Songs of Protest (1953; reprinted as a paperback in 1960), John Greenway called "John Henry" the "best-known (and best) Negro ballad, the best-known Negro work song, the best song of protest against imminent technological unemployment." [21]

While collected folk songs and literary retellings of the John Henry theme

poured into print, only one or two folk tales landed in the net of collectors. A

curious folk narrative, mixing tall-tale elements of the Wonderful Hunt, the

Great Eater, and Schlaraffenland with heroic and erotic legends, was told to

Howard Odum in 1926 by a Negro construction camp worker in Chapel Hill.[22]

Yet subsequent Negro tale collections added only one substantial text to the

John Henry tradition, while a whole cycle of trickster John tales dating from

slavery times were being uncovered.[23] A folk tale volume of 1943, prepared by

the Federal Writers' Project in North Carolina, contained a graphic and fantastic

prose tradition of John Henry's birth, deeds, and death in the contest

with the steam drill on the Santa Fe Railroad. Data are given on the informant,

an aged Negro of Lillington, North Carolina, who asserted John Henry was

born north of him on the Cape Fear River, and worked with him on the Santa

Fe road, but the text is obviously edited.[24] The talented Negro novelist and

folklorist, Zora Neale Hurston, explicitly asserted in Mules and Men (1935)

that the ballad was the only folklore item connected with John Henry.[25]

The greatest impact of John Henry on American culture has come outside

the printed page through commercial recordings. In 1962 the most widely

recorded folk song sold to the public was "John Henry." That year the Phonolog

Record Index listed some fifty current renditions of the ballad "John

Henry" and fifteen of the work song "Nine Pound Hammer." As many popular

singers have made recordings for the general public as have folk singers for

collectors in the field. The Library of Congress Copyright Catalogue reveals

over one hundred song titles devoted to John Henry from 1916 on, embracing

all kinds of musical arrangements from simple melodic line and text to full

orchestral composition. Arrangers staking out claims include: the well-known American composer, Aaron Copland; the Negro song-compiler, John W. Work; the musicologist, Charles Seeger; the celebrated Negro ex-convict, Huddie Ledbetter (Lead Belly); W. C. Handy, the "father of the blues"; concert arranger, Elie Siegmeister; and popular singer Bob Gibson. Chronologically, only ten copyrights are registered before 1937, ten in the period 1938- 1945, twenty from 1946-1954, and eighty from 1955-1963.[26] While the general popularity of "John Henry" has dramatically climbed in the past decade,

fresh field texts are rarely reported.[27] Still the commercial recordings are frequently traditional or semitraditional in source.[28]

Popular singers and recording artists have altered the formless sequence of

independent stanzas which comprised the folk ballad into a swift-moving,

tightly knit song story. John Henry has shifted from the sphere of Negro

laborers and white mountaineers into the center of the urban folk song revival

and the entertainment world of jukebox and hootenanny, radio and television.

The earlier texts from tradition show the usual variation characteristic of

folklore. John Henry drives steel chiefly on the C&O, but once it is located in

Brinton, New Jersey, and he also drives on the AC and L, and Air Line

Road, the L and N, and the Georgia Southern Road. He comes from Tennessee

most often, but also from East Virginia, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama.

His hammer weighs nine, ten, twelve, sixteen, twenty and thirty

pounds; sometimes he carries a hammer in each hand. His girl is named

Julie Ann, Polly Ann, Mary Ann, Martha Ann, Nellie Ann, Lizzie Ann, and

Mary Magdalene. In one unique text, John Henry's partner kills him with

the hammer. Among the visitors to his grave are, in one instance, Queen

Elizabeth.

Yet the shifts and twists of tradition are perhaps less surprising than the

tenacity and recurrence of key phrases, lines, and stanzas. Analyzing his thirty-odd texts, Guy Johnson determined that the three most frequent

stanzas, and therefore probably the earliest, were the opening stanza of John

Henry sitting on his papa's (or mama's) knee, the declaration to his captain,

"A man ain't nothin' but a man," and the verse about his gal dressed in red,

Polly Ann. Otherwise, the story line varied considerably, and Johnson observed,

"The stanza, not the song, is the unit" (p. 87), a conclusion later supported

by Alan Lomax. Phonograph, radio, and record-player have however

given the episodic stanzas of the ballad a structure and symmetry; already in

1929 Johnson could list eleven examples of "John Henry" on commercial

records, and in 1933 Chappell added eleven more. One of the most astute folk

song scholars in America, Phillips Barry, believed that mountain white song

tradition, perhaps in the person of John Henry's white woman, helped stabilize

the ballad. He pointed to its parallelism with the opening stanza of the

well-known old English ballad of "Mary Hamilton":

When I was a babe and a very little babe,

And stood at my mither's knee,

Nae witch nor warlock did unfauld

The death I was to dree.

"Mary Hamilton" and other English and Scottish ballads lingered in the

southern mountains and so could easily have influenced the new ballad.29

Today the ballad of John Henry lives on in remarkably stable form for an

anonymous oral composition. It has been refashioned by the urban folk song

revival into a national property, shared by singers and composers, writers and

artists, listeners and readers. The ballad commemorates an obscure event in

which several lines of American history converged-the growth of the railroads,

the rise of the Negro, the struggle of labor. Various interpreters have

read in the shadowy figure of John Henry symbols of racial, national and

sexual strivings. Negro and white man, teenager and tot, professor and performer,

have levied upon the John Henry tradition. The explanation for

these multiple appeals lies in the dramatic intensity, tragic tension, and simple

poetry combined in one unforgettable American folk ballad.[30]

Indiana University

1. "Ballads and Songs of Western North Carolina," Journal of American Folklore, XXII (1909), 249.

2 "Songs and Rhymes from the South," Journal of American Folklore, XXVI, 163-165.

3. "Some Types of American Folk-Song," Journal of American Folklore, XXVIII, 14.

4. "John Hardy," Journal of American Folklore, XXXII, 505-520; and Folk-Songs of the South (Cambridge, Mass.: 1925), pp. 175-188. The same identification of John Henry with

5. John Hardy was made by Dorothy Scarborough, On the Trail of Negro Folk-Songs (Cambridge, Mass.: 1925), pp. 218-222.

6. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1928), pp. 189-191, "John Henry." a (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press).

7. Ibid.

8. (Jena: Frommannsche Verlag, Walter Biedermann).

9. Between the two monographic studies, various related items were published. Chappell demanded an explanation from Johnson in American Speech, VI (Dec., 1930), 144 ff. Lowry C. Wimberly wrote a note in admiration of Johnson's John Henry and praised the ballad as great literature, for its theme "of the individual pitting his lone strength and courage against an environment" and "its ringing hammer music" and portrayal of "the struggle of sentient humanity against the unfeeling machine" (Folk-Say, A Regional Miscellany, ed. B. A. Botkin

10 Johnson, John Henry, p. 150.

11. Published by Harper and Brothers (New York & London: 1939). Josh White played the part of Blind Lemon, a folk singer, and in his 25th anniversary album (ca. 1955) recorded "The Story of John Henry," based on songs in the stage production (Elektra Records 1 123-A). Time and Newsweek carried notices on Jan. 22, 1940, and Theatre Arts in its March issue

(XXIV, 166-167). Roark Bradford wrote a piece for Collier's on "Paul Robeson in John Henry"

(Jan. 13, 1940), pp. 105 f.

12 Howard W. Odum and Guy B. Johnson, Negro Workaday Songs (Chapel Hill: 1926), p.221;

13. Carl Sandburg, The American Songbag (New York: 1927), p. 24 ("In southern work camp

gangs, John Henry is the strong man, or the ridiculous man, or anyhow the man worth talking

about, having a myth character somewhat like that of Paul Bunyan in work gangs of the Big Woods

of the North"); R. M. Dorson, "Paul Bunyan in the News, 1939-1941" Western Folklore, XV

(1956), 193, citing newspaper notices of the Bradford-Wolfe music-drama in which John Henry

was likened to Paul Bunyan.

14 The chapter "John Henry, the Steel Driving Man" in Frank Shay, Here's Audacity! (New

York: 1930), pp. 245-253, was based on Guy B. Johnson's chapter in Ebony and Topaz, A

Collectanea, ed. Charles S. Johnson (New York: 1927), pp. 47-51, "John Henry-A Negro

Legend."

15. The titles are Carmer, The Hurricane's Children (New York and Toronto: 1937), "How John Henry Beat the Steam Drill Down," pp. 122-128; Miller, Heroes, Outlaws and Funny Fellows (New York: 1939), "John Henry's Contest with the Big Steam Drill," pp. 147-157; Malcolmson, Yankee Doodle's Cousins (Boston: 1941), "John Henry," pp. 101-107; Carmer, America Sings (New York: 1942), "John Henry," pp. 174-179; Blair, Tall Tale America (New York: 1944), "John Henry and the Machine in West Virginia," pp. 203-219; Leach, The Rainbow Book of American Folk Tales and Legends (Cleveland and New York: 1958), "John Henry," pp. 33-35.

16. One such volume, Their Weight in Wildcats (Boston: 1946), carried only the name of the

illustrator, James Daugherty, on the title page. The selection of hero tales reprinted from earlier

volumes was made by an editor, Paul Brooks, at Houghton Mifflin, the publisher. For John

Henry he reprinted the statements of one of Guy B. Johnson's informants, Leon R. Harris of Moline, Illinois. Brooks saw in John Henry only "brute strength and dumb courage" (p. 170).

17 Ray M. Lawless, Folksingers and Folksongs in America (New York: 1960), pp. 12-13.

18A Treasury of American Folklore (New York: 1944), pp. 230-240; A Treasury of Southern

Folklore (New York: 1949), pp. 748-749; A Treasury of Railroad Folklore (New York: 1953), pp.

402-405.

"9The Editors of Life, Life Treasury of American Folklore (New York: 1961), pp. 168-169.

Other popular publications to retell the story of John Henry and reprint a ballad text are

Freeman H. Hubbard, Railroad Avenue (New York: 1945), pp. 58-64, "The Mighty Jawn Henry";

The Book of Negro Folklore, ed. Langston Hughes and Arna Bontemps (New York: 1958),

"John Henry," pp. 345-347; American Heritage, XIV (Oct., 1963), 34-37, 95, Bernard Asbell,

"A Man Ain't Nothin' but a Man."

20Alan Lomax( The Folk Songs of North America (New York: 1960), pp. 551-553. For the

work song, cf. Chappell, p. 99, Support for Lomax's position is given by Roger D. Abrahams in

his note and ballad text on John Henry as a sexual hero of South Philadelphia Negroes (Deep

Down in the Jungle, Hatboro, Pa.: 1964), p. 80.

21 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), p. 107. Reprinted as paperback by A. S.

Barnes & Co. (Perpetua edition, 1960).

22. Negro Workaday Songs, pp. 238-240.

23. There is no connection between the trickster John cycle and John Henry, as Alan Lomax

suggests (The Folk Songs of North America, p. 553). For folk tales of John the slave and his Old

Marster, see R. M. Dorson, Negro Folktales in Michigan (Cambridge, Mass.: 1956), chap. 4, and

Negro Tales from Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and Calvin, Michigan (Bloomington, Ind.: 1958), pp.

43-62.

24. Bundle of Troubles and Other Tarheel Tales, ed. W. C. Hendricks (Durham, N. C.: 1943),

pp. 37-51, "John Henry of the Cape Fear." (Told by Glasgow McLeod to T. Pat Matthews.)

25 Hurston, Mules and Men (Philadelphia and London: 1935), p. 306. She prints nine "verses of

John Henry, the king of railroad track-laying songs," pp. 80-81, 309-312.

26 This information was kindly supplied to me by Joseph C. Hickerson, Reference Librarian

in the Archive of Folk Song, Library of Congress.

'27Field-collected texts are reported by G. Malcolm Laws, Native American Balladry (Philadelphia:

1950), p. 231. "John Henry" is I1 in his index. He refers to thirty-nine recordings from

eleven states and the District of Columbia in the Library of Congress folk song archives, including

five releases. He cites, in addition to works already mentioned, Mellinger E. Henry, Folk-Songs

from the Southern Highlands (New York: 1938), pp. 441-442, 446-448, for a text and many

references. In Folk-Songs of Virginia, A Descriptive Index and Classification (Durham, N.C.:

1949), p. 294, Arthur K. Davis lists six John Henry texts collected between 1932 and 1934. Only

one full text of eight stanzas is presented in The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina

Folklore, Vol. II, Folk Ballads (Durham, N.C.: 1952), 623-627. The editors, H. M. Belden and

A. P. Hudson, say, "Few if any folk songs of American origin have been so extensively and

intensively studied as John Henry."

28 Some representative examples of commercially released "John Henry" recordings currently

available, which appear indebted at least indirectly to traditional southern Appalachian sources,

are Laurel River Valley Boys, Music for Moonshiners (Judson L3031); Mainer's Mountaineers,

Good Ole Mountain Music (King 666); Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys, New John Henry

Blues (Decca 45-31540); George Pegram and Walter Parham, Banjo Songs from the Southern

Mountains (Riverside RLP 12-610); Harry Smith, Anthology of American Folk Song (Folkways;

re-recordings of early hillbilly and race records), No. 18, Williamson Brothers and Curry,

"Gonna Die with my Hammer in my Hand" and No. 80, Mississippi John Hurt, "Spike Driver

Blues"; Merle Travis, Back Home (Capital T891). Neil Rosenberg and Mayne Smith kindly

furnished me information for this list from their personal record collections.

29 Phillips Barry, review of L. W. Chappell, John Henry, in Bulletin of the Folk-Song Society

of the Northeast, VIII (1934), 24-26. As further evidence of "non-tunnel" influences, Barry cites

a "John Hardy" tune transferred to "John Henry" but known only to white mountaineers.

30 That new surprises are still possible in the career of John Henry was shown in the remarkable

paper by MacEdward Leach presented at the regional meeting of the American Folklore

Society at Duke University on April 23, 1964, "John Henry in Jamaica," suggesting the possibility

of the John Henry tradition's originating among Jamaican Negroes.