CHAPTER XV

TYPES OF PHONO-PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORDS OF NEGRO SINGERS

We have referred often in these pages to the wealth of material found in the great variety and number of the Negro's songs. We have appraised the collections which have been published and those which are to come as valuable source material for the study of folk life and art and especially for their value in the portrayal of representative Negro life. Adequate analysis and presentation of these values will be possible only after a number of the other collections have been completed and comprehensive studies made.

There are other values not yet presented. For example, the scientific study of the Negro's musical ability has barely begun, but it promises much. The work of Professor Carl E. Seashore and others has resulted in the formulation of various tests and methods for studying musical talent and singing ability. Many valuable studies have been reported from various psychological laboratories. One of the latest developments in this field is the phono-photographic method of recording voices. In this method the phono-photo-graphic machine makes it possible to take pictures of sound waves of all kinds. Among other things, it registers the most delicate variations in pitch, variations which are often too subtle for the human ear to perceive. In short, it gives a picture of exactly what a voice or a musical instrument does.

Naturally this method of sound wave analysis may be of untold value in the study of the human voice. It enables the singer to see his voice in detail. It furnishes the scientist with data for the study of the qualities which make a voice good or poor. It opens up many possibilities, both practical and theoretical, as a method of voice analysis.

Of special interest and importance is the application of this method to the study of Negro singers and Negro voices. It was therefore a fortunate turn of circumstances which made it possible for the authors of this volume to join Professor Seashore and Dr. Milton Metfessel of the University of Iowa in making extensive phono-photographic studies of various Negro singers during the fall of 1925, with headquarters at the University of North Carolina Institute for Research in Social Science. Professor Seashore was able to cooperate personally in the work at Hampton, while Dr. Metfessel remained throughout the entire period of the study. [1]

Among the types of Negro singers whose voices were subjected to the phono-photographic process were practically all of the common types which we have been recording in the pages of this volume and of The Negro and His Songs. There were the typical laborers, working with pick and shovel. There was the lonely singer, with his morning yodel or "holler." There were the skilled workers with voices more or less trained by practice and formal singing. There was the more nearly primitive type, swaying body and limb with singing. The noted quartet from Hampton Institute, as well as individual singers there, cooperated. Men and women from the North Carolina College for Negroes represented other types. Quartets and individuals from the high schools at Chapel Hill and Raleigh, North Carolina, were still other types.

Finally the voices of one hundred and fifty Negro children from the Orange County Training School at Chapel Hill and the Washington School at Raleigh were recorded. Types of songs included in the experiments were the gang work song, the pick-and-shovel song and various other work songs, the yodel, the "1926 model laugh," the blues, formal quartet music, spirituals, and children's songs. It would thus appear that both the selections and the numbers were adequate to make a valuable beginning in a new phase of the subject.

The results of this study will be published fully later. The present chapter is in no sense a report of the results. It is intended merely to describe the phono-photographic study, to give some examples of records obtained during the study, and to indicate certain possibilities of this method as a scientific means of research into Negro singing abilities and qualities.

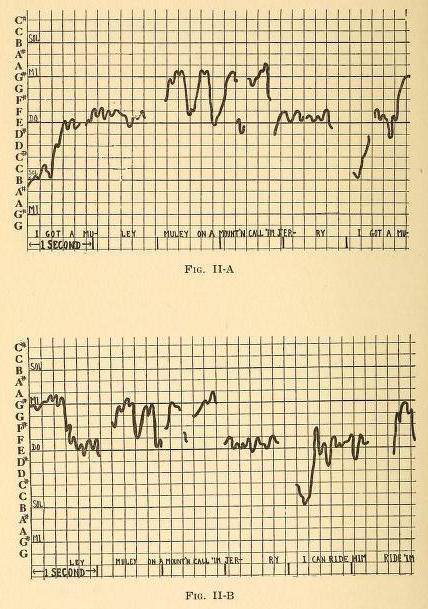

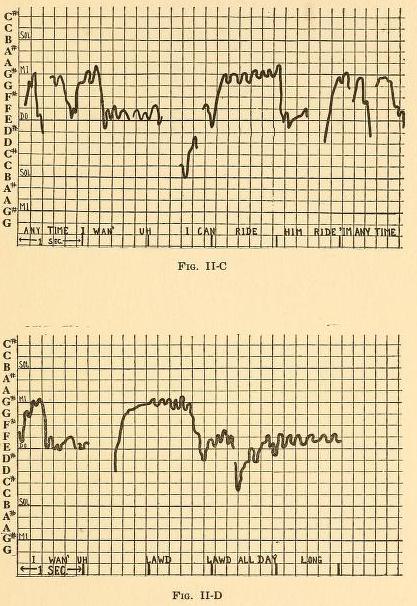

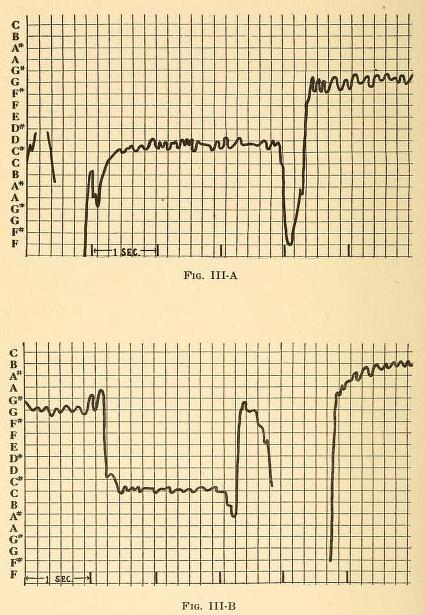

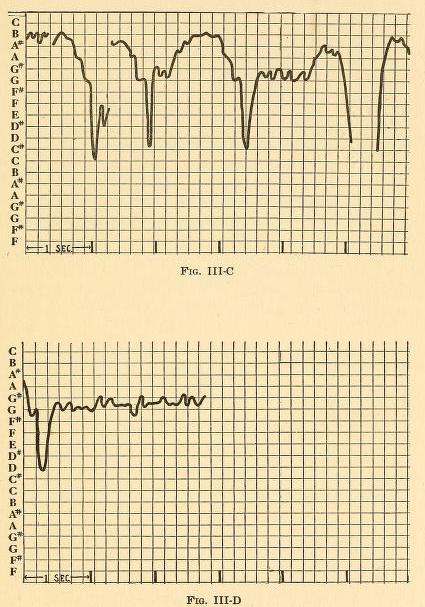

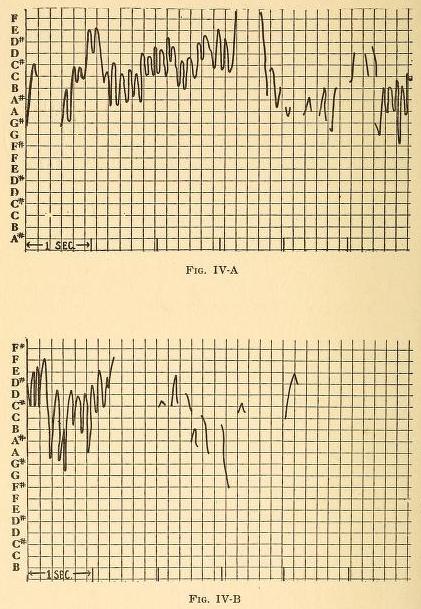

The following explanation will suffice to acquaint the reader with the method of reading the photographic records presented in this chapter. Along the left side of each graph are the notes of the scale in half steps. When the heavy line which represents the voice rises or falls one space on the graph, the voice has changed a half tone in pitch. Time value is shown along the bottom of the graph. The vertical bars occurring every 5.55 spaces along the bottom mark off intervals of one second.

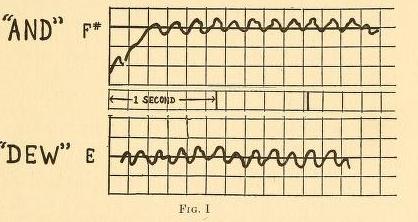

If one were to sing a perfectly rigid tone, its photographic record would be a horizontal straight line. Such a thing is very rare, however, in any type of singing, for most sustained tones photograph as more or less irregular wavy lines. Indeed, a voice whose sustained tones photographed as a straight line would not produce as good tones as one with rapid and regular variations of the vocal cords. A good singing voice possesses what is called the vibrato. In terms of the photographic records, the pitch vibrato consists of a rise and fall of pitch of about half a tone about six times a second. In Figure I are given samples of tones photographed by Seashore and Metfessel from the singing of Annie Laurie by Lowell Welles. The first represents the singing of the word "dew" in the line, "Where early fa's the dew." The second is the word "and" from the line, "And for bonnie Annie Laurie." The vibrato is present in both tones. Note how the voice line varies above or below the note E on "dew" and F-sharp on "and," sometimes as much as a quarter of a tone. Note also the smoothness and regularity of the pitch fluctuations. It is this smoothness of the vibrato which characterizes good singing.

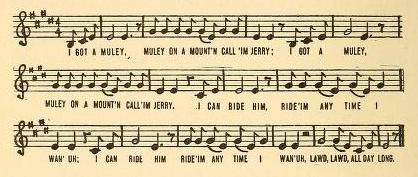

To illustrate their scope, methods, and possibilities three specimens of photographic records of Negro voices are presented : a song, / Got a Muley, [3] by Odell Walker; a yodel or "holler," as it is commonly called, by Cleve Atwater; and Cleve's "1926 Model Laugh."

Figure II is the photographic notation of I Got a Muley. The music of the song as best it can be represented in ordinary notation is given below. Several interesting things are revealed by the song picture in Figure II. [4] For one thing, we have here a picture of some of those elusive slurs which are so common among Negro singers. Take the words "muley on a mount'n" in Figure II-A, for example.

When one hears these words as they were sung by Odell Walker, one is apt to feel that with the exception of the last syllable of "mount'n" they are all sung on the same pitch. The graph shows that this is not so. There are really drops in pitch of one and a half or two whole tones at two places in this phrase. Or take the word "ride," as it occurs in the phrase, "ride 'im any time I wan' uh," which phrase occurs twice in the song. One can tell while listening to the song that there is some sort of slur present, but it is impossible to tell by means of the ear alone exactly what is happening. The graph reveals the fact that the singer actually begins the word "ride" between D-sharp and E and carries it as high as G-sharp. The outstanding tone heard, however, is G-sharp. Other pitch changes not shown in the ordinary musical notation may be easily detected by the reader.

The vibrato is present in places in the record of this song. It section A there is a trace of it on the word "muley" the first time it occurs. In section B there is an approach to it on the word "Jerry." In section C it occurs on the word "ride" the first time it appears. In section D there is a tendency toward it on "Lawd, Lawd," but is shows best in "long", the last word of the song. A comparison with the examples of artistic singing in Figure I shows that our Negro workman's vibrato is rough and irregular and that it does not maintain a steady general pitch level as does Welles's vibrato. It must be borne in mind, however, that this particular song does not afford good opportunties for sustained tones and that the Negro singer's vibrato might have shown to better advatnage on a different song.

In Figure III is a picture of a yodel or "holler." It is the sort of thing which one hears from field hands as they go to work in the morning, or from some gay-spirited pick-and-shovel man as he begins digging on a frosty morning.

No attempt is made to include the ordinary musical notation of the yodel, for it would give but a suggestion of the vocal idiosyncrasies involved in the execution of the yodel. The most remarkable thing about this record is the sudden changes of pitch which it portrays. In Figure III-A just at the beginning of the fifth second interval the voice takes a sudden drop. Then it rises from F to G in the octave above in about a third of a second. In section B of the yodel, near the end of the fifth second interval, the same spectacular rise occurs, this time from F-sharp to G-sharp in about one-tenth of a second. Still more remarkable are the several rapid rises and falls in pitch in section C. In the production of such sudden changes the vocal cords must undergo a snap. Even in speech, where pitch changes are very rapid, such sudden ascents and descents do not occur.

It is also interesting to note that the vibrato is present at times in the yodel. It is fairly plain on C-sharp along the middle of section A and still better on G at the end of the same section. It also shows at the end of section B, continuing into section C; and the yodel ends with a semi-vibrato. There is an approach to it in several other places. The vibrato of our Negro worker, however, is rather erratic and wavering in comparison with the vibrato of the vocal artist in Figure I. Yet one must remember that our subjects, both in Figure II and Figure III, were Negro workers whose voices have never had a touch of formal

training.

In Figure IV [below] we have a photographic record of a hearty Negro laugh. Its musical quality is at once evident. In the first three seconds of the laugh there is an unusual effect. It would not be called a vibrato because the pitch changes are too rapid and too extensive to give the vibrato effect. Near the beginning of the fifth second of the laugh the voice breaks up into a series of interrupted speech sounds. During the sixth second it suddenly becomes musical again and remains so for about two seconds. Then, after a rest, (see section B) the speech sounds reappear and continue intermittently to the end of the laugh.

These observations indicate some of the possibilities of the phono-photographic method of studying Negro voices and Negro songs. When the complete results of the recent study are ready for publication we may have data which will make it possible to compare scientifically the voices of different kinds of Negro singers as well as the voices of Negro and white singers.

Other studies and correlations may be made through the articulation of the moving pictures of the singers, their faces, their bodily movements, their emotional expressions, and whatever reactions the camera may reveal. In nearly all instances where phono-photo-graphic records were made of Negro voices in the recent study, moving pictures were made of the singers. In

addition to these, moving pictures were made of groups of workmen while singing. Some remarkable examples of skill in movement, of coordination of song with work, of mixture of humor, pathos, and recklessness with work and song were brought to light. These have been incorporated into a series of three reels. Some of these pictures of facial expression during singing will be included in the report of the study when it is published in complete form.

Many interesting questions may find their solutions if the scientific method is applied to the study of Negro singing ability. Is the vibrato a native endowment? Is the vibrato more frequent among Negroes than among whites? At what age does it appear in the voice? [5] What other qualities cause the rank and file of Negroes to excel as singers? Is the Negro's capacity for harmony greater than the white man's? Is his sense of rhythm better? These are some of the questions which science should be able to answer in the near future.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Dr. Metfessel, using the perfected machine which long years of work at the University of Iowa psychological laboratories have produced, was successful in obtaining a large number of satisfactory records. He also took

moving pictures of the singers. Needless to say, we are indebted to him for the material of this chapter.

[3] The tune is slightly different from the music of the song of the same name given in Chapter XIV. It is variously called / Got a Mule on the Mountain, I Got Mule Named Jerry, I Got a Muley, Jerry on Mountain.

[4] A measure on the graph is equivalent to approximately nine spaces on the horizontal scale. Note that the singer did not keep accurate time. His measures range from six to twelve spaces.

[5] A study of the voices of white and Negro school children now being made by Milton Metfessel and Guy B. Johnson may throw some light upon some of these questions.