BAHAMA SONGS AND STORIES

by Charles Edwards 1895

[This page has the Title Page; Preface; Contents; Introduction; Appendix (Negro Music Song Notes); Bibliography. The Songs are attached on one page and the Stories on another. The songs were collected in the late 1880s and early 1890s and show a direct parallel to African-American spirituals and folk songs.]

Channel between a "Cay'' and "the Main"

A Village Street

BAHAMA SONGS AND STORIES

A CONTRIBUTION TO FOLK-LORE

BY

CHARLES L. EDWARDS, Ph. D.

PROFESSOR OF BIOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI

« « «

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

Published for the American Folklore Society

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

LONDON: DAVID NUTT, 270, 271 STRAND

LEIPZIG: OTTO HARRASSOWITZ, QUERSTRASSE, 14

Copyright, 1895,

By The American Folk-Lore Society.

The Riverside Press Cambridge Mass. U.S.A.

Electrotyped and printed by H. O. Houghton and Company.

To

MY FATHER AND MOTHER

------------------------------------------------------------------

PREFACE

While this work is intended as a contribution to folk-lore, yet it is hoped that the songs and stories will appeal to those not specially interested from the scientific standpoint. The genetic relation existing between the tales and music of the Bahama and of the United States negroes will be readily discerned. Parallels from accessible collections of American, and of native African, folk-lore are indicated. The material for this paper was collected during the sum-mer of 1888, at Green Turtle Cay, of 1891, at Harbour Island, and of 1893, at Bimini. The stories I.-XI., and XXXIV., and a portion of the Introduction, were published in "The American Journal of Psychology," vol. ii. No. 4, Worcester, 1889; and stories XXXI. and XXXV.- XXXVIII., in the "Journal of American Folk-Lore," vol. iv, Nos. XII. and XIV^, Boston and New York, 1891. I wish to express my thanks to President G. Stanley Hall, who has kindly permitted me to use again the material which appeared in "The American Journal of Psychology" to Mr. A. E. Sweeting, of Harbour Island, Bahamas, who was good enough to note down the music to most of the songs ; and to Mr. William Wells Newell, for valuable advice and assistance in connection with the publication.

C. L. E

University of Cincinnati,

June, 1895.

-----------------------------------------------------------

CONTENTS

Introduction 13

SONGS

I. I Looked o'er Yander 23

II. Lord, I wish I could Pray 24

III. Hail! King of the Jews 25

IV. Didn't it Rain, my Elder 25

V. Git on Board 26

VI. Who built de Ark? 27

VII. Beautiful Sta'h 27

VIII. Go Down, Moses 28

IX. Dear Sister, yi Feet Strike Zion 28

X. Love bro't de Savye' down 29

XI. When de Moon went down 30

XII. Jesus heal the Sick 31

XIII. O! Look-A Death 32

XIV. I tho't I Saw My Brothe' 33

XV. Everybody wants to Know 34

XVI. Ev'ry Day be Sunday 35

XVII. Good News in the Kingdom 36

XVIII. Dig my Grave Long and Narrow 37

XIX. I Wish I Could Pray 38

XX. Don't you feel the Fire a-burnin' 39

XXI. Opon de Rock 40

XXII. Turn Back an' Pray 41

XXIII. Come out the Wilderness 42

[XXIV. Um Died once to Die no Mo' 43

XXV. Thb-r Heaven Bells are Ringin' 44

XXVI. Jesus bin Hyere 45

XXVII. Do You Live by Prayer? 45

XXVIII. I can't stay in Egypt Lan' 46

XXIX. Nothin' but the Righteous 47

XXX. Death was a Little T'ing 48

XXXI. My Jesus led me to the Rock 49

XXXII. Com' 'long, Brother 49

XXXIII. Never a Man Speak like this Man .... 50

XXXIV. Goin' to Ride on de Cross 51

XXXV. Don't you Weep after me 52

XXXVI. Oh I We all got Religion 55

XXXVII. I Wan' to Go to 'Evun 57

XXXVIII. I Long to See That Day 58

XXXIX. Lawd, Remember me 59

XL. We 'll git Home by and by 60

STORIES

I. B' Rabby in de Corn-Field 63

II. B' Helephant and B' Vw'ale 65

III. B' Rabby, B' Spider, an' B' Bouki 65

IV. B' Man, B' Rat, an' B' Tiger-Cat 66

V. B' Bouki an' B' Rabby 67

VI. B' Baracouti an' B' Man 68

VII. B' Loggerhead and B' Conch 69

VIII. B' Crane-Crow, B' Parrot, and B' Snake 70

IX. B' Cricket and B' Helephant 70

X. B' Crane-Crow an* B' Man 71

XI. De Big Worrum 72

XII. B' Rabby an' B' Tar-Baby 73

XIII. B' Big-Head, B' Big-Gut, an' B' Tin-Leg. ... 75

XIV. B' Rabby had a Mother 76

XV. B' Man, B' Wobian, an' B' Monkeys y6

XVI. B' Rabby, B' Bouki, an' B' Crow 77

XVII. De Man an' de Dog 79

XVIII. B' Loggerhead, B' Dog, an' B' Rabby 80

XIX. B' Devil an' B' Goat 80

XX. B' Hellibaby an' B' Dawndejane 82

XXI. 'Bout A Bird 83

XXII. A Young Lad an' 'is Mother 84

XXIII. B' Parakeet an' B' Frog 85

XXIV. 'Bout B' Dog, B' Cat, B' Rabbit, an' B' Goat 86

XXV. The Lady an' 'er Two Dawtahs an' 'er Husband 87

XXVI. A Young Lady an' 'er Son 87

XXVII. B' Goat, B' Bouki, an' B' Rabbit 88

XXVIII. The Woman an' 'eh Husban' 89

XXIX. B' Big-Head an' B' Little-Head 90

XXX. A Boy an' Sheep 90

XXXI. De Girl an' de Fish 91

XXXII. Three Boys an' One Woman 92

XXXIII. A Lady an' 'er Two Dawtahs 93

XXXIV. B' Jack an' B' Snake 94

XXXV. B' Little-Clod an' B' Big-Clod 95

XXXVI. De Woman an' de Bell-Boy 97

XXXVII. Greo-Grass an' Hop-o'-my-Thumb 97

XXXVIII. De Debble an' Young Prince had a Race 99

Appendix 101

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Channel between a "Cay" and "the Main" (front)

A Village Street (Front)

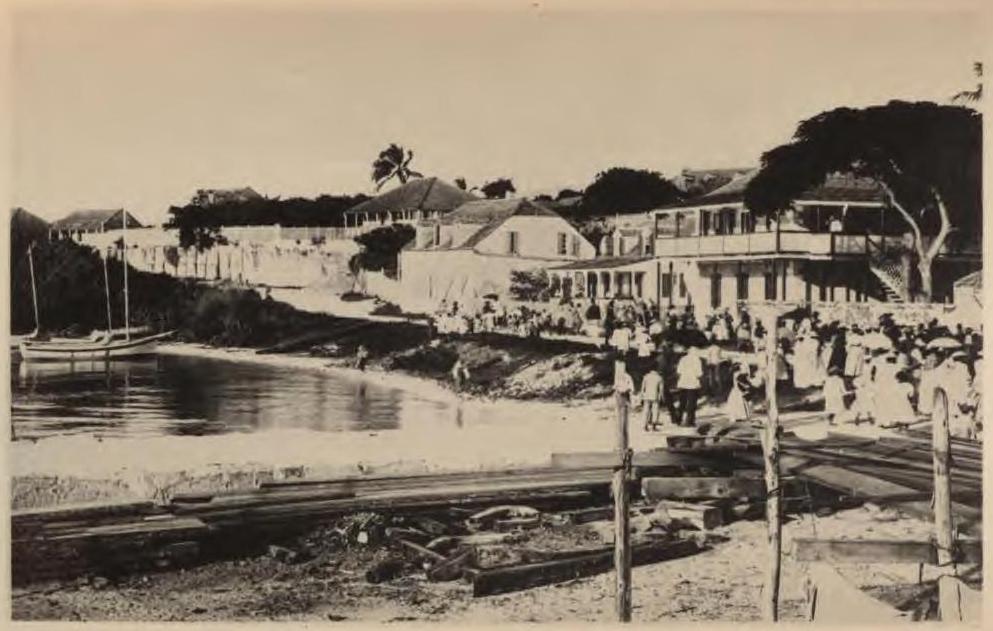

Celebration of Emancipation, Harbor Island 18

A Group of Children

Celebration OF Emancipation — the Procession 84

Scene at the Celebration of Emancipation 90

BAHAMA SONGS AND STORIES

---------------------------------------------------------------

INTRODUCTION

The Bahamas include over three thousand islands, most of which are quite small. As a whole, these islands, not being separated by great distances, present a striking homogeneity, both in their coralline origin and in the life and surroundings of the people. Just as the biologist acquires an insight into the complex problems of structure and function presented by a living thing, by comparing its life-history with the environment, so in studying a folk-lore, a knowledge of its philosophy is gained by considering the life-history of the community in which the folk-lore has developed in relation to the surrounding conditions.

In the Bahamas are found a most interesting succession of three generations of coral formations. First is the main island, sometimes from fifty to one hundred miles long and from one to ten miles wide, with hills reaching the height of one hundred feet, and forests of large pine-trees.

Then extends the chain of cays [From the Spanish cayo, a rock] a few miles to seaward, each from a few acres to three or four square miles in area, seldom being more than one half or three quarters of a mile wide, with hills not higher than eighty feet. Upon these cays, with the exception of the cocoa-palms, grow only small bushes and stunted trees, while coral plantations still flourish on the ocean side.

Lastly arises still farther at sea the present reef, with living polyps almost to the crest, where, broken into caps of foam, the waves from the deep Atlantic are somewhat arrested in their impetuous course.

Seen from a distance, the islands appear as dark, low-lying sandbars, but when closely approached the vegetation, as intensely green as the deep sea is blue, adds beauty to the monotonous land. The coralline sand of the shore is made up of the triturated skeletons of corals and of echinoderms, the shells of mollusks, and the stony secretions of many other animals and of algae. It is washed over and over by water as pure as crystal, and bleached in the sun of unending Summer until it becomes as white as snow. The shoals about are also of this constantly shifting sand, and so the shallow water is rendered a chalky green shade, affording a remarkable contrast with the wonderful blue of the subtropical sea. [These shoals sometimes reach gigantic proportions, as in the Great Bahama Banks, where, for over hundreds of square miles, the water is but a few fathoms in depth. Upon these shallows, beyond the sight of land, one has the peculiar impression of sailing over a submerged Sahara, or an infinite mill-pond!]

Between " the main" island and its series of satellite cays extends a generally navigable channel, which, protected from the ocean swell and yet with every advantage of the ocean breeze, affords an excellent roadstead for vessels. Here the water takes on every shade over the white sand, according to the varying depth, from palest green to deepest blue. It is a sight of peculiar beauty to see, in the early morning, the small boats of the natives, which, with large white sails, are almost like gulls skimming over the transparent waters.

As nature first leaves the coral island, there is but little soil, and so the plants found are such as can adapt themselves at the

root to crannies in the rock and thus gain some sustenance from the mould of their ancestors, while from the air the leaves breathe in the rich supplies of gases and moisture. The formation longest exposed, the main island, has thus accumulated the most soil, and supports forests or prairies of considerable extent. The first settlements were in some cases made by families of loyalists who fled from the American colonies during the Revolution, while in other cases the colonists have come directly from Great Britain. The towns have grown slowly, for the most part by the natural increase of the few first families; and, because of repeated intermarrying among these family stocks, at present nearly all of the people are interrelated.

The population is about evenly divided on the basis of color, although, as in the West Indies, the percentage of increase of the negroes over the whites is becoming greater every year. Whether the pessimistic predictions of Trollope and of Froude, of negro supremacy and a return to African barbarism, shall be fulfilled in the Bahamas, as apparently already in Hayti, it is difficult to say. The comparatively poorer soil of the Bahamas, compelling the negro to work if he would survive, will be a strong factor in keeping up the civilization already attained.

Usually, among the " out islands," the town is found upon one of the cays, on the side facing the channel. Imagine a seacoast town in North Carolina, isolated as much as possible from railroads and ocean steamers, and its people leading a seafaring life with farmwork at odd intervals, transport it to a small coral island, then you can gain a very fair outline for the picture of one of these Bahama towns. But there are touches of local coloring quite necessary to complete the picture.

Horses and carriages are rarely found on the " out " islands, so roads for their accommodation are not essential, and the streets are often not wider than a city sidewalk. The squares into which the town is divided are proportioned to the streets in size, so that the first effect is of an overgrown doll-town! The streets are made by smoothing off the naturally jagged points left by the action of water upon the coral sandstone of which the cay is composed, and they are of dazzling whiteness. The houses are generally of frame, three or four sometimes crowded upon the same small lot, and, whenever the owner can afford the display, painted white, a most disagreeable continuation of the glare from the street and seashore.

The principal industries are the raising of pineapples, oranges, and sisal, and the gathering and curing of sponges. Many ships are of native manufacture, and all the lads, from the earliest years, are taught the various trades of the sea. The sea, too, is a storehouse of food, for fish is to the Bahaman what beef is to the Englishman, and nowhere will one find the fish more delicious. Sweet potatoes, cocoanuts, bananas, oranges, sapodillas, avocado-pears, plantains, soursops, star-apples, rose-apples, and many other tropical luxuries add to the delights of the table.

The fields are scattered along " the main " for ten miles on either hand, whither the men sail in the morning, coming back at night.

The chief farming implements in the Bahamas, as has been aptly said, are the pickaxe and the machete. With the former a natural crevice in the rock is somewhat widened, and therein a pineapple slip or some seed is planted ; while with the machete, a long, broadsword sort of knife, the weeds and bushes arc cut down.

The Bahamas have been subjected to periodical booms. Before the days of the lighthouses, "wrecking" was the most profitable business. Many richly-laden vessels went to pieces on the treacherous coral reefs, and the people of the nearest communities secured, in the name of salvage, a large percentage of the valuables from the wreck. The story is told that when one of the governors was going back to England he asked, at a farewell meeting, what he could do of most importance for the colony. With one voice the people said, "Have the laws establishing the lighthouses repealed!"

Then sugar became the one thing to raise, and only after much expensive machinery had been imported was it discovered that the soil was not rich enough to grow sugar, Then blooded horses for the American market claimed attention, but a lack of proper diet for the horses ended that enterprise, Now it is sisal, the plant which in Yucatan has given the world most of its best hemp. The native Bahama variety is said to produce a better quality of fibre than that of Yucatan ; so everybody is raising the young plant, and thousands of acres of previously unoccupied lands are being devoted to the culture of sisaL There seems a fair chance that this industry will prove of lasting benefit to the colony.

The Bahama people are intensely pious. The whole social life centres in the church. Those mad days of the buccaneers are gone. For the ribald songs of the riotous pirates we have the solemn hymns of the Wesleyans, and the chant of the English Church. Lighthouses have taken from the coral reefs their former terror. The laws against swearing are quite severe; and, what is even more necessary, the good old patriarch, who holds all the offices from chief magistrate to street commissioner, is strict in the enforcement of the laws, so that the ordinary street talk is quite a relief to one who is familiar with the profanity of American streets.

The colored people, everywhere gossipy, good-natured, and religious, having here been emancipated for over fifty years, have become somewhat educated and unusually independent. Socially the races are more nearly equal than anywhere else on the globe. Schools and churches are occupied in common. Miscegenation, so prevalent in Nassau, the capital, has not prevailed in the " out " islands to any extent. Of course, in each community one may find a circle of intelligent white people to whom the negroes can never be more than servants. But to keep up this satisfactory relation is every year a more perplexing problem. Some of the first negroes who came to the cays were slaves of the loyalists ; but aside from these, the large majority indeed, have come by direct descent from native Africans. There yet lives in Green Turtle Cay one old negro, " Unc' Yawk," who, bowing his grizzled head, will tell you, " Yah, I wa' fum Haf'ca."

It is with the negroes that one associates the picturesque and beautiful surroundings in the Bahamas. Their huts, so often

thatched with palmettos, are built on the low, sandy soil of the town. There grow the graceful cocoa palms with long, green leaves which rustle as sadly as do those of oak and chestnut in the autumn woods of the north, suggesting the gentle murmur of falling raindrops. There, too, the prickly pear, like an abatis, bristling all over with needles, seems to guard the luxuriant blossoms of the great oleander bush, dispensing sweetest perfume from its midst. Apparently every hut has its quota of a dozen little black "Conchs," [The native Bahamans have been nicknamed " Conchs," from the predominance there of a mollusk of that name.] of as sorted sizes, who think the palmetto-thatched cottage a palace and the yard a menagerie, wherein the pigs and chickens and dogs are animals created for their special amusement.

There are but few stoves and chimneys in the Bahamas. Boiling and frying are done in a small shed, over an open fire built on a box of sand; while for the baking is employed an oven of the same sort as our foremothers knew by the name of the "brick oven." It is a cone, made of coral sandstone, into the upper half of which is hollowed an oven. The "mammy" and children do most of the housework; while the lord and master, when not at sea or on the farm, plays checkers or lies in a hammock reading a novel.

There is one piece of work, however, in which husband and wife share, and that is the chastisement of the children. They chastise with a club, and regularly every twenty-four hours the screaming of the tortured child comes from the hut, or surrounding bushes, to tell its sad tale of remaining barbarism; but the negro child has a disposition full of sunshine, and in a few moments after being beaten will sing like the happiest being on earth.

The evening is the playtime of the negroes. The children gather in some clump of bushes or on the seashore and sing their songs, the young men form a group for a dance in some hut, and the old people gossip. The dance is full of uncultured grace ; and to the barbaric music of a clarionet, accompanied by tambourines and triangles, some expert dancer " steps off " his specialty in a challenging way, while various individuals in the crowd keep time by beating their feet up (in the rough floor and slapping their hands against their legs. All applaud as the dancer finishes ; but before he fairly reaches a place in the circle a rival catches step to the music, and all eyes are again turned toward the centre of attraction. Thus goes the dance into the night.

The strangest of all their customs is the service of song held on the night when some friend is supposed to be dying. If the patient does not die, they come again the next night, and between the disease and the hymns the poor negro is pretty sure to succumb. The singers, men, women, and children of all ages, sit about on the floor of the larger room of the hut and stand outside at the doors and windows, while the invalid lies upon the floor in the smaller room. Long into the night they sing their most mournful hymns and "anthems,'* and only in the light of dawn do those who are left as chief mourners silently disperse. The "anthem " No. 1 (given below) is the most often repeated, and, with all the sad intonation accented by tense emotion of the singers, it sounds in the distance as though it might well be the death triumph of some old African chief! Each one of the dusky group, as if by intuition, takes some part in the melody, and the blending of all tone-colors in the soprano, tenor, alto, and bass, without reference to the fixed laws of harmony, makes such peculiarly touching music as I have never heard elsewhere.

As this song of consolation accompanies the sighs of the dying one, it seems to be taken up by the mournful rustle of the palms, and to be lost only in the undertone of murmur from the distant coral reef. It is all weird and intensely sad.

This custom of coming together and singing all night is generally called the "settin' up." It has its merry as well as its sad side. On great occasions, as "Angus eve night," the celebration of the emancipation of African slaves on British soil, and "Chris'mus," the "settin' up" gives us the negro in his best mood. It is about two hours after nightfall, when the sun dropping like a great golden ball below the distant sea-line has surrendered the sky to the myriad stars, that the dusky forms of the negroes begin gliding into the scene of the "settin' up." It is a long time beginning, with much mirth and joking and gleaming of "ivory." But at last the largest room of the largest hut is filled with chairs, and the chairs with gayly dressed colored folk. One man, better dressed than the others and probably better educated, "lines off," in sonorous voice, the words of some good old hymn.

Around the centre table with him are the principal singers, and standing back of these, with a shining "beaver" on his head as a badge of office, is the leader. He lifts his hands, his face shines with pride, his rich baritone voice pours forth the line, and the hymn begins. Then all voices, joining together every shade of tone, send out into the beautiful night that rapturous, voluptuous music of the civilized Africans. The hymn swells, the ivory teeth gleam, and the wave of sound rolls on. The leader reaches out his great hands, as if to raise the song aloft, and shouts his commands of "Not so fas', now!" "Min' de word!" and other encouraging words, while his body sways back and forth.

Then the old men interject their admonitions, "Not so much talkin'!" "Dem ladies dere is la'flSn' too much!" "Now, j'ine in!" and so on. The hymns continue until after midnight, when comes a pause, with refreshments of coffee and bread. After this

come the "anthems," or folk-songs, that have not been learned from a book. The negro sings now ; body, soul, voice, smile, eyes, all his being sings, as if he were created only for music! Some woman or man carries the refrain and all "j'ine in," from the wise patriarch, with his crown of yellow-gray wool, to the veriest pickaninny. But how can one describe this music, vibrating in the dead of night to the pulse-beats of human hearts ? As well try to describe the song of the thrush or the voice of the palm!

The folk-tales are most popular among the children, and indeed are handed down from generation to generation principally by them.

Celebration of Emancipation, Harbor Island

After the short twilight and the earlier part of the evening, when singing and dancing amuse the children, comes the story-telling time par excellence. This is usually about bedtime, and the little "Conchs" lie about upon the hard floor of the small hut and listen to one of the group, probably the eldest, "talk old stories." With eyes that show the whites in exclamation, and ejaculations of "O Lawd ! " "Go'!" "Do now!" etc., long drawn out in pleasure, the younger ones nestle close together, so " De Debbie " won't get them, as he does " B' Booky " or " B' Rabby " of the story.

These tales are divided into two classes, "old stories" and fairy stories; the former particularly constituting the negro folk-lore, while the latter have been introduced from the same sources as the ordinary fairy tales of English children. It is often difficult to make the class distinction, for it is a curious fact that some of the fairy tales have been translated, so to speak, into old stories, and one easily recognizes in such a tale as " B' jack an' de Snake " its English ancestor of Jack the Giant-Killer.

The folk-lore proper is mostly concerning animals, which, personified, have peculiar and ofttimes thrilling adventures. Where, in our own negro-lore, the animals are called "Brer" by Harris, and "Buh" by Jones, among the Bahama negroes the term is contracted to "B'," and so one finds in " B' Rabby, who was a tricky fellow," the "Brer Rabbit " whom Uncle Remus has made famous to us as the hero of the folk-lore of the South.

The conventional negro dialect, generally used in our American stories, will apply to the Bahama negroes only in part ; for their speech is a mixture of negro dialect, "Conch" cockney, and correct English pronunciations. In the following stories, which are given as nearly as possible verbatim, this apparent inconsistency will be noticed, for in the same story such expressions, for example, as " All right " and " Never mind " may be given in the cockney "Hall right" in negro dialect "N'er min', " or pronounced as written in correct English, and one never knows which pronunciation to expect.

In these stories one readily detects the influence of physical environment and the play of native invention in the predominance given to those animals and plants locally prominent, acting their parts among scenes borrowed from local surroundings. On the other hand, the introduction of the hon, elephant, and tiger suggests an heredity from African ancestors ; while similarly the rabbit, in the title role of hero, as rabbits are not indigenous to the Bahamas, points to the influence of American negro-lore. The isolation of the "out" islands from foreign influences, the scanty supply of books and newspapers, and the great lack of what are generally termed amusements, have given especially good conditions for the development of a folk-lore at once recognized as peculiar and sectional.

An indescribable flavor is added to these tales by the environment of the people. An island out in the Atlantic arises, with low

shores, from that indescribable blue water, and is covered by the paler blue of the skies of "Summerland." Heated by the glaring sun of midday, the smooth streets and long, hard beaches dazzle one with their whiteness; or, bathed in silver radiance by the queen of night, these bare spaces stretch out like great ghosts of themselves, cloaked in the grim darkness of surrounding vegetation.

Querulous gulls catch fish in the tide-pools; cunning little lizards, from orange-tree and stone wall, watch your every step ; and along the ocean beach sand-crabs swiftly run to the sheltering holes when you approach. In the clear water of the sea-gardens, one beholds the fans and feathers of the sea waving in response to tide and billow, and beneath them the creeping stars, the spiny urchins, and long, brown sea-cucumbers crawling among the tentacled annelids and anemones. Chasing in and out, above and around these more simply organized creatures, are fishes, banded in gold and black and orange, with long, waving filaments to their fins, and high foreheads which solemnly suggest an intellect only developed in higher forms.

Then, finally, those colonies of coral animals which inhabit the top of a submarine precipice built of the skeletons of their ancestors through millions of generations, and which erelong will die to complete the foundation for another island or series of islands, are the highlights, as well as the shadows, of the picture.

There is perpetual beauty on land and in the sea, while the balmy, equable air invites one to sail over the blue waters, or to lie in a hammock beneath the palms and listen to some black "Conch" "talk old stories." In each community one boy becomes much the best story-teller, and from such a source I took most of the following tales. But the quick, short gesture, the peculiar emphasis on the exciting words and phrases, the mirth now bubbling from eyes which anon roll their whites in horror, in short the Othello part of the tales, I cannot give.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

APPENDIX

NEGRO MUSIC

The subject of negro music has received such a varied treatment from so many writers, in the course of the present century, that it seems impossible to say anything new. But as a matter of folklore, — not from the standpoint of musical analysis, — the character of negro music in Africa and in America may be reviewed, and certain genetic relationships between the primitive and the civilized music indicated.

Waitz[1] (p. 237) says of the native Africans in general that without question they, of all primitive races, possess the most considerable gift, and the most decided preference, for music; and Hartmann [2] characterizes instrumental music, dancing, and singing as the element in common of the happy, pleasure-seeking Africans.

The musical instruments, of which Ratzel [3] (p. 149) says no other primitive people possess such a multiplicity, have been described by every student of African ethnology.

Throughout Africa the drum is the chief instrument. It varies in size from that of a cylinder a number of feet long to that of the

smallest kettle-drum. At certain festivals of the Betschauen, a number of women encircle an ox-hide, and then, stretching it, beat upon it with long sticks, and so, according to Ratzel [3] (p. 148) originated the drum. There is the greatest variety of stringed instruments, from the one-stringed violin, simple lutes, and harps to a zither of seventeen strings. A gourd is used as a resonance-box, and for strings the hairs of an elephant's tail are generally employed.

Johnston [4] (p. 434) says the natives of the Congo produce upon the five-stringed lyre melodies both quaint and touching: and according to Hahn (see Ratzel, [3] p. 170) the Bushmen can play beautiful tunes upon an old European violin, or upon the native substitute. Pan-pipes, and simple flutes, long clarinet-like wooden trumpets, and war-horns made of ivory or antelope-horn, are universally distributed. Among the best instruments are the balafo and the marimbo, from which we have the xylophone. They are constructed of a series of from fourteen to twenty graduated keys of hard-wood bars, underneath wHich are fastened gourds to form resonance-chambers, and, as in the xylophone, the keys are struck with little hammers. The

music of a band of these instruments is wild, chromatic, and rich in discords. (Hartmann,[2] p. 197.)

Schweinfurth, [5] describing the great festivals of the Bongo, says (p. 288): "The orchestral results might perhaps be fairly characterized as cats' music run wild. Unwearied thumping of drums, the bellowings of gigantic trumpets, for the manufacture of which great stems of trees come into requisition, interchanged by fits and starts with the shriller blasts of some smaller horns, make up the burden of the unearthly hubbub which reechoes miles away along the desert. Meanwhile women and children by the hundred fill gourd-flasks with little stones, and rattle them as if they were churning butter; or again, at other times, they will get some sticks or dry faggots and strike them together with the greatest energy."

The dance takes place at night, about a great fire, and is especially enjoyable when there is moonlight. Rum, beer, and palm-wine excite the dancers to Pandean excesses. The movements of wild animals are cleverly imitated. The dance, often sensual, is accompanied by the stamping of feet and the clapping of hands, orchestral music, and singing.

Concerning these orgies Schweinfurth * (pp. 354, 355) gives a most vivid description: " Slowly and mournfully some decrepit old man or toothless old woman begins with broken voice to babble out a doleful recitative; ere long, first one and then another will put in an appearance from the surrounding huts, and point with the forefinger at the original performer, as if to say, 'This is all his fault,' when suddenly all together they burst forth in universal chorus, taking up the measure, which they work into a wondrous fugue. At a given signal the voices rise in a piercing shriek, and then ensues a series of incredible contortions: they jump, they dance, and roll themselves about as though they had bodies of india-rubber; they swing themselves as if they were propelled with the regularity of machines; it would almost seem as if their energy were inexhaustible, and as if they would blow their trumpets till their lungs gave way, and hammer at their drums till their fists were paralyzed. All at once everything is hushed; simultaneously they make a pause, but it is only to fetch their breath and recover their strength, and once more the tumult breaks out as intense as ever." Page 289: " Difficult were the task to give any adequate description of the singing of the Bongo.

It must suffice to say that it consists of babbling recitative, which at one time suggests the yelping of a dog and at another the lowing of a cow, whilst it is broken ever and again by the gabbling of a string of words which are huddled up one into another. The commencement of a measure will always be with a lively air, and every one, without distinction of age or sex, will begin yelling, screeching, and bellowing with all his strength; gradually the surging of the voices will tone down, the rapid time will moderate, and the song be hushed into a wailing, melancholy strain. Thus it sinks into a very dirge, such as might be chanted at the grave, and be interpreted as representative of a leaden and a frowning sky, when all at once, without note of warning, there bursts forth the whole fury of the negro throats ; shrill and thrilling is the outcry, and the contrast is as vivid as sunshine in the midst of rain."

In the singing, one voice generally leads, and the chorus regularly alternates with the solo. Among the Sotho (Endemann,[6] p. 30) the vocal solo begins in a high register, and, regardless of any rule, goes to the lower notes. At the dance, and among the laborers at work in company, choruses are sung in perfect time to the movement of the performers.

The solo singer divides at will the lines of the text, often beginning in the middle and afterwards singing the first part. Sometimes there are two choruses. One will begin the cadence in a higher, the other in a lower pitch, and these may be sung together, or follow each other. Besides the wild and stormy choruses of the nocturnal carousals, there is abundant evidence of sweeter and more tender songs. Heuglin (Ratzel, [3] p. 516) says that the songs of the Upper Nile negroes are very harmonic. They are mostly of a melancholy nature, as so many real folk-songs are, and, too, in a minor key. The Bushmen (pp. 3, 69) and the Hottentots (pp. 3, 103) have an especial musical talent, and, after once or twice hearing songs like "O Haupt voU Blut und Wunden " and "Long, Long Ago," although not understanding the words, they will sing

them through correctly. Among the Waganda (pp. 3, 465, 466) are singers of great renown, who are kept at court to improvise in praise of the king. The following from Wilson is addressed to King Mtesas : —

"Thy feet are hammers,

Thou son of the woods.

Great is the fear of thee,

Great is thine anger,

Great is thy peace,

Great thy power."

Du Chaillu ^ heard at night a chant for the dead, which he describes as a wail whose burden seems to be "There is no hope."

The words were as follows : —

^ Lion.

*' Oh, you will never speak to us any more,

We cannot see your face any more,

You will never walk with us again,

You will never settle our palavers for us.**

(Cf. Laing® (pp. 233, 237), Waltz ^ (pp. 240,243) and Endemann®

(pp. n^ 63).)

Although the words of these primitive compositions are often senseless, as sometimes happens in the songs of the Southern negroes of the United States, yet they are just as freely applauded.

The best-developed music is that of Dahomey, which has been brought to complete accord ; and that of Aschanti, which moves in fifths and octaves, but seldom in thirds.

Now, turning to America, we find, in the many articles and books written about the negro, a large number of references to his music, of which we can only give those most pertinent. Stedman (pp. 258-290) describes the negroes of Guinea as found in slavery in Surinam Guiana. The musical instruments, the dance, and vocal

music had suffered scarcely any modification from American environment. This, no doubt, was due to the constant infusion of native Africans, as at that time the importation of slaves was unlimited

In a defence of slavery published at Paris in 1802-3, an "ancient counsellor and colonist of San Domingo," signing himself V. D. C.,^ says of the negroes (p. 331) : "They are so musically inclined that all their pleasure consists in the pipe and dance ; nay, negroes have performed in the oratorios of St. Domingo. Their songs and tales run generally on love, either in a lamentation, a hymn, or a satire, and they will join in the choruses with the leader." Here, too, is a near approach to primitive African conditions.

Cable ^^ describes the dances of the Creole slaves, which before

1843 were celebrated on the Sabbath afternoons of summer, in

Place Congo, New Orleans. The instruments of the orchestra were

primitive African drums and wooden horns, the marimbabrett, Pan's

pipes, gourds filled with pebbles or grains of corn, and the jawbones

of oxen or horses, over the teeth of which metal keys were rattled.

These native African instruments were reinforced by triangles, jews'-

harps, and banjos, which are always associated with the American

negro. Cable agrees with Harris, however, that the favorite musical

instrument of the Southern negro is not the banjo, but the fiddle.

These dances were essentially of primitive African nature, with

survivals from many different tribes represented. As they were

gradually suppressed, there arose instead the "shout" (described

farther on), and the various forms, often complicated, of the shufl3e

and the double shufl3e, with the natural addition of the various

dances in vogue with the white people.

rst*3fstinctive period of American negro vocal music was the

era of negro minstrelsy ushered in about 1835 with the song "'Jim

Crow." ^ Then " Zip Coon," " Long-tailed Blue," " Ole Virginny

Nebber Tire," and " Settin' on a Rail " soon followed, and became

universally popular. The airs were whistled, sung, and played by

everybody, everywhere. They voiced the happier hours of the slave,

and were so true to nature, and so appealed to the genuine Ameri-

can heart, that for a few years these simple ballads became the

songs of the nation. With "Ole Dan Tucker," perhaps the most

famous of all, these ballads reached their highest mark. Soon after

1S41, a mass of spurious sentimental songs and miserable parodies

flooded the country, and negro minstrelsy fell into disrepute. The

real minstrel, who loved the sunshine and the moonlight of the old

plantation, was displaced by the corked imitation of the stage.

Brown ^^ gives the following classification of the songs of the

slave : —

(r.) Religious Songs, e. g. "The Old Ship of Zion," where the re-

frain of " Glory, halleloo," in the chorus, keeps the congregation well

together in the singing, and allows time tor the leader to recall the

next verse.

(3.) River Songs, composed of single lines separated by a barbar-

ous and unmeaning chorus, and sung by the "deck-hands" and

" roustabouts," mainly for the howl.

(3.) Plantation Songs, accompanying the mowers at the harvest,

in which strong emphasis of rhythm was more important than

words.

(4.) Songs of Longing ; dreamy, sad, and plaintive airs describing

the most sorrowful pictures of slave life, sung in the dusk when

returning home from the day's work.

(5.) Songs of Mirth, whose origin and meaning, in most cases for-

gotten, were preserved for the jingle of rhyme and tune, and sung,

with merry laughter and with dancing, in the evening by the cabin

fireside.

(6.) Descriptive Songs, sung in chanting style, with marked em-

phasis and the prolongation of the concluding syllable of each

line. One of these songs, founded upon the incidents of a famous

horse-race, became almost an epic among the negroes of the slavehold-

ing States.

Concerning the songs of the negroes of the regions bordering the

Gulf and the Caribbean Sea, which show in a special manner the in-

fluence of French and Spanish music, Cable" (p. S05) says : " It is

strange to note in all this African-Creole lyric product how rarely its

producers seem to have recognized the myriad charms of nature.

His songs were not often contemplative. They voiced, not outward

nature, but the inner emotions and passions of a nearly naked ser-

pent-worshipper, and these looked not to the surrounding scene

for sympathy ; the surrounding scene belonged to his master. But

love was his, and toil, and anger, and superstition, and malady.

Sleep was his balm, food his reinforcement, the dance his pleasure,

rum his longed-for nepenthe, and death the road back to Africa.

These were his themes, and furnished the few scant figures of his

verse."

The most important of these classes of songs is undoubtedly that

of the religious songs, or " spirituals," as they were generally called.

They were at first often connected with the " shout," a certain sur-

vival of the primitive African dance, and were then called " running

spirituals." The best description of the "shout" is given by a

writer in " The Nation," ^ May 30, 1867, who says: "When the

'sperichir is struck up, they begin first walking, and by and by

shuffling round, one after the other, in a ring. The foot is hardly

taken from the floor, and the progression is mainly due to a jerk-

ing, hitching motion, which agitates the entire shouter, and soon

brings out streams of perspiration. Sometimes they dance silently,

sometimes as they shuffle they sing the chorus of the spiritual, and

sometimes the song itself is also sung by the dancers. But more

frequently a band, composed of some of the best singers and of tired

shouters, stand at the side of the room to " base " the others, sing-

ing the body of the song and clapping their hands together or on

their knees." In the " hand-shake," or " love-feast," ^^ which follows

the general services in the negro church, is found an interesting

modification of the " shout."

Of the singing, Allen ^"^ (p. iv.) says: "The voices of the colored

people have a peculiar quality that nothing can imitate; and the

intonations and delicate variations of even one singer cannot be

reproduced on paper. And I despair of conveying any notion of

the effect of a number singing together, especially in a complicated

shout, like " I can't stay behind, my Lord," or " Turn, sinner, turn,

O ! " There is no singing in parts as we understand it, and yet no

two appear to be singing the same thing : the leading singer starts

the words of each verse, often improvising, and the others, who

" base " him, as it is called, strike in with the refrain, or even join in

the solo, when the words are familiar. When the "base" begins,

the leader often stops, leaving the rest of his words to be guessed

at, or it may be they are taken up by one of the other singers. And

the " basers " themselves seem to follow their own whims, beginning

when they please and leaving off when they please, striking an oc-

tave above or below (in case they have pitched the tune too low or

too high), or hitting some other note that chords, so as to produce

Appendix. 109

the effect of a marvellous complication and Variety, and yet with the

most perfect time, and rarely with any discord. And what makes it

all the harder to unravel a thread of melody out of this strange net-

work is that, like birds, they seem not infrequently to strike sounds

that cannot be precisely represented by the gamut, and abound in

"slides from one note to another, and turns and cadences not in

articulated notes." And Harris ^ (p. 11) says of these songs : " They

are written, and are intended to be read, solely with reference to

the regular and invariable recurrence of the caesura, as, for instance,

the first stanza of the Revival Hymn : —

Oh, whar | shill we go | w^en de great | day comes, |

Wid de blow | in' er de tnimpits | en de bang | in' er de drums ? |

How man | y po' sin | ners '11 be kotch'd out, late |

£n fine | no latch | ter de gold | in' gate. |

" In Other words, the songs depend for their melody and rhythm

upon the musical quality of time, and not upon long or short, ac-

cented or unaccented syllables."

The words of these spirituals are generally either taken from the

Bible, or suggested from texts therefrom which abound in imagery.

(For collections of songs see Pike,^ Armstrong,^ Harris,^^,*

Deming,2i Trotter,^^ Woodville,^^ and Fortier.^*)

They may, however, come from a very different source. Higgin-

son ^ (p. 692) gives this account of the genesis of one, from the lips

of the originator. " Once we boys," he said, " went for tote some

rice, and de nigger-driver he keep a-callin' on us ; and I say, * O, de

ole nigger-driver.' Den anudder said, 'Fust ting my mammy tole

me was, notin' so bad as nigger-driver.' Den I made sing, just put-

tin' a word, and den anudder word." From such an origin, or from

the fevered imagination of some great exhorter passing through the

fiery furnace of a negro revival, arose most of these songs. Lines,

or parts of lines, of one song are often sung to the music of another,

and almost any combination of words can be sung to any tune. Oc-

tave Thanet^ says, "They all have the same characteristics, an

erratic melody, a formless yet sometimes brilliant imagination, per-

vading melancholy, and no trace of what we call sense."

The use of the pentatonic scale (the fourth and seventh being

omitted) was noted in the music of the natives of the Congo (John-

ston,* p. 434), and also in over half of the songs of the Jubilee Singers

(Seward ^^). This, however, is a characteristic of all barbaric mu-

sic, but, together with many traits mentioned above, shows in this

case, a sustained relationship to primitive African music. On the

contrary, from the frequent occurrence of melodies borrowed from

hymn-books, as e. g, the refrain of the jubilee song, " I 'm So Glad,"

which is the same as the first half of Fleyel's Hymn, we can im-

no Appendix.

agine the great influence of the music of the white people upon

the imitative negroes. The well-known custom of sitting up and

singing all night, noticed of the Southern negroes (Woodville^, and

which is such a striking feature of Bahama life (see Introduction),

has been described among the native tribes of Africa by every

explorer. We may, I think, safely say that the American negro has

largely borrowed the higher music of the civilized white people, into

which he has breathed the weird poetic feeling inherited from his

naked ancestor who sang and danced in the African moonlight

After his emancipation, the negro, impressed with the dignity and

responsibility of his position, and under the ban of a severe struggle

for existence, becomes more serious, and less given to the jollifications

which were so natural on the old plantation. Secular songs and

dancing are beginning to fade away, and a new class of music more

imitative of that of the white man'is coming in vogue. Sad indeed

will be the loss if these wonderful melodies, formed from a union of

the highest music of civilization with the best that is found among

all primitive peoples, should pass away forever.

A few of the songs in this volume may have been heard among

the negroes of the Southern States, although, so far as I know, none

have appeared in the published collections. Syllables may be omit-

ted at the whim of the singer, and the same words sung to the

music of several songs.

1 Waitz, Theodor, AnthropolgU der Naturvblker, ii Bd., Negervolker, Leip-

zig, i860.

^ Hartmann, R., Die Volker Afrikas^ Leipzig, 1879.

• Ratzel, Friedrich, Vblkerkunde^ i Bd., Die Naturvolker Afrikas, Leipzig, 1885.

• Johnston, H. H., The River Congo, from its Mouth to B6l6b6, etc., London,

1884.

• Schweinfurth, Georg, The Heart of Africa, vol. ii., London, 1873.

• Endemann, K., " Mittheilungen iiber die Sotho-Neger," Zeitschriftf Ethno-

logie. Heft L, Berlin, 1874.

' Du Chaillu, Paul B., Explorations ank Adventures in Equatorial Africa, New

York, 1871.

8 Laing, Major A. G., Travels in Western Africa, London, 1825.

• Stedman, Captain J. G., Narrative of a Five Years* Expedition against the

Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of S, America, etc,

vol. ii., London, 1796.

^<* Examen de lEsclavage en general, et particulierement de P Esclavage des Nh

gres dans les Colonies franqaises de PAmerique, par V. D. C, Paris, 1802-3, R^^*

in Edinburgh Rev, vol, vi. pp. 326-350, 1805.

" Cable, George W., " The Dance in Place Congo," The Century Magazine,

vol. xxxi. pp. 517-532, February, 1886.

^ "Negro Minstrelsy, Ancient and Modem," Putnam's Magazine, vol. v.

pp. 72-79, January, 1855.

^ Brown, John Mason, " Songs of the Slave," LippincotPs Magazine, voL ii.

pp. 617-623, December, 1868.

Appendix^ 1 1 1

*^ Cable, George W., " Creole Slave Songs," The Century Magazine^ vol.

xxxi. pp. 807-828, April, 1886. A number of songs with music.

" Allen, W. F., " Negro Dialect," The Nation, vol. i. pp. 744, 745. Descrip-

tion of the " shout."

^'^ Hopkins, Isabella T., Scribner's Monthly ^ vol. xx. pp. 422-429, 1880. A

vivid description of the negro church service.

1^ Slave Songs of the United States, New York, 1867. Introduction by W.

F. Allen. 136 songs with music, representing the entire South.

^** Harris, Joel Chandler, l/ncle Remus j His Songs and his Sayings, New York,

1880. Nine songs, words only, two of which are " spirituals " and the rest are

secular.

^^ Pike, G. D., The Jubilee Singers, etc., Boston and New York, 1873. 61 re-

ligious songs.

^ Armstrong, Mrs. M. F., and Ludlow, Yl^Vf ., Hampton and its Students, New

York, 1874. With 50 Cabin and Plantation Songs.

^ Deming, Clarence, By- Ways of Nature and Life, New York, 1884, pp. 370.

Negro Songs and Hymns. Negroes of the Mississippi Bends, from Helena, Ar-

kansas, to Vicksburg, Miss.

^ Trotter, Jas. M., Music and Some Highly Musical People, Boston and

New York, 1878. Biographical sketches of some famous negro singers like The

Black Swan, Blind Tom, The Luca Family, etc., with selections of instrumental

music composed by negroes.

® Woodville, Jennie, " Rambling Talk about the Negro," Lippincotfs Maga-

zine, vol. xxii. November, 1878.

^ Fortier, Alc^e, Trans, and Proc, of the Mod, Lang. As, of Am, vol. iii.

Baltimore, 1888, pp. 159-168.

® Higginson, T. W., " Negro Spirituals." Atlantic Monthly, vol. xix.

June, 1867. A collection of 36 religious and 2 secular songs.

* Harris, Uncle Remus and his Friends, Boston and New York, 1892. Wrth

16 songs, words only.

^ Octave Thanet, Jour, Am, Folk-Lore, vol. v., 1892. Words of 3 songs.

ADDITIONAL NOTES TO THE STORIES.

I. p. 54. Among a number of nominies used by the country-folk in England,

reproduced from the London Globe, April 28, 1890, in Jour, Am, Folk-Lore, vol.

viii., 1895, p. 81 and p. 153, is the following: —

Be bow bended, my story 's ended.

If you donH like it, you may mend it ;

A piece of [Sudden for telling a good un,

A piece of pie for telling a lie.

This, instead of some forgotten African phrase, may be the source of e, bo, ban,

Cf. I. and X., Fort\er, Louisiana Folk- Tales, Memoirs of the Am. Folk- Lore Soc.

vol. ii., Boston and New York, 1895, pp. 7, 29.

II* P* 55> Island of Mauritius, Gerber, Jour, Am, Folk-Lore, vol. vi. 1893, p.

250 ; I., Fortier, /. c, p. 3.

III. p. 55, Bouki is Ouolof for hyena. Fortier, /. c, p. 94.

IV. p. ^6, Qi, XVIII., Chatelain, Folk-Tales of Angola, Memoirs of the Am.

Folk-Lore Soc. vol. i., Boston and New York, 1894, p. 157.

X. p. 61, Gerber, /. c, p. 253.

XII. p. 63, Gerber, /. c, p. 251 ; XII., Fortier, /. c, p. 35.

XVI. p. 67, Gerber, /. c, p. 251.