CHAPTER XIV

SOME TYPICAL NEGRO TUNES

We have pointed out again and again the utter futility of trying to describe accurately the singing of a group of Negroes when they are at their best. A group of twenty workers singing, carrying various parts, suiting song to work, and vying with one another for supremacy in variations and innovations — this is a scene which defies musical notation and description. And yet the picture which we have tried to present in this volume would certainly be incomplete without the addition of some of the simple melodies of typical workaday songs. They are added, therefore* merely as final touches to the picture rather than as attempts to reproduce the complex harmonies of Negro songs. Heretofore the spirituals have received most of the attention of those who were working toward the preservation of Negro music. The secular songs have nothing like the standardization of words and music that the spirituals have, simply because they have not been preserved. It is inevitable, however, that due attention will be given to Negro secular music. Indeed much has recently been done toward that end. [1] But the task of recording the majority of Negro secular tunes is yet to be done. It is to be hoped that the forth coming volume of secular songs which is. being edited by James Weldon Johnson will go a long way toward giving the Negro's secular music the place which it deserves.

Any one who has tried to record the music of Negro songs knows that it is very difficult to do more than approximate the tunes as they are actually sung. Several reasons may be cited to account for this. In the first place, there are slurs and minute gradations in pitch in Negro songs which it is impossible to represent in ordinary musical notation. Some of these effects can be reproduced on a stringed instrument, but they cannot be shown on a musical scale which is only divided into half-step changes of pitch. A notation in the form of curved lines would come nearer representing the Negro's singing than does the system of definite notes along a staff. It is what the Negro sings between the lines and spaces that makes his music so difficult to record.

Another factor which must be reckoned with is the inconsistency of the singer. When the recorder thinks that he has finally succeeded in getting a phrase down correctly and asks the singer to repeat it "just one more time," he often finds that the response is quite different from any previous rendition. Requests for further repetition may bring out still other variations or a return to the previous version. Again, after the notation has been made from the singing of the first stanza of a song, the collector may be chagrined to find that none of the other stanzas is sung to exactly the same tune. The variations are not marked. They are elusive and teasing, and they add beauty to the song.

How often the song collector wishes for some instrument which will record group singing in its native haunts! He cannot hope to catch by ear alone all of the parts — and there are undoubtedly six or eight of many of these songs — that go into the making of those rare harmonies which only a group of Negro workers can produce. If he coaxes the singers to keep repeating their song, some of them become self-conscious and drop out. Perhaps the whole group will refuse to sing any more. If perchance he gets one or two singers to give him some special help, he gets but a suggestion of the group effect. He must be contented with securing the leading part of the song and harmonizing it later as best he can.

So these rare work harmonies have never been faithfully reproduced in musical notation. [2] Rather than give an artificial harmonization to the tunes recorded in this chapter, we are presenting only the leading part of each song.

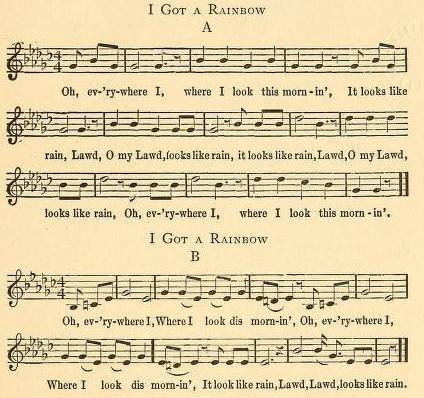

Since several of the songs in this chapter are work songs, let us examine for a moment the technique of the worker-singer. Many work songs, of course, are not really work songs except in the sense that they are sung during work. When the work is such that it does not necessitate continuous rhythmic movements, one song is about as good as another. But rhythmic movements, being especially adapted to song accompaniment, have given rise to a distinct type of work song. Digging, hammering, steel-driving, rowing, and many other kinds of work fall in the rhythmic class. The technique for all of these is practically the same.

Let us take digging as an example, since it is a very common type of Negro labor in the South. Typical pick-song patterns are as follows:

I got a rainbow,

Rainbow 'roun' my shoulder;

I got a rainbow,

Rainbow 'roun' my shoulder;

'Tain't gonna rain,

Lawd, Lawd, 'tain't gonna rain.

Well, she asked me

In her parlor

An' she cooled me

Wid her fan;

Lawd, she whispered

To her mother,

"Mama, I love

That dark-eyed man."

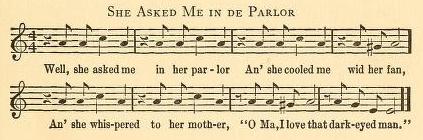

Now in the type of song illustrated by the first of the above patterns the strokes of the pick are not all of equal length. The rhythm of the song demands a short stroke alternated with a longer stroke. In the second type of song, however, the meter is such that all of the strokes of the pick may be of equal length. At the end of each line there is a caesura or pause. This represents the time during which the worker swings his pick from the upright position to the ground. When the pick strikes the ground, the worker gives a grunt, loosens the pick, and raises it. It is during this loosening and upward movement that he sings. The down-stroke calls for much more effort than raising the pick, so he rarely ever sings on the down-stroke. The time required for a digging stroke is, however, shorter than the time required for loosening and raising the pick, so that ordinarily the pauses in the song are relatively brief.

It is in a group that the work song is to be heard at its best. When a group is digging and singing, picks are swung in unison. On a few occasions we have observed that one or two men took their strokes out of unison in order to singcertain exclamations or echoes during the pauses in the singing of their com panions. This, however, is a rare procedure, for the most striking variations in both music and words can be introduced without breaking the unison of the strokes.

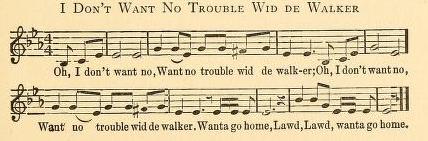

To call a song a pick song does not mean that it is not also a good song for general purposes. I Got a Rainbow, I Don't Want No Trouble Wid de Walker, and other pick songs are quite effective when sung as solos with guitar accompaniment. On the other hand, many general songs can easily be converted into pick songs by slight changes in meter. [3]

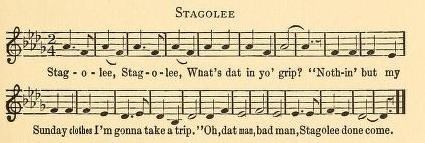

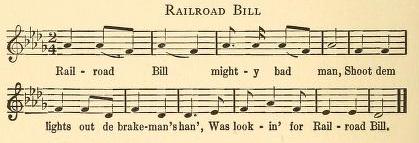

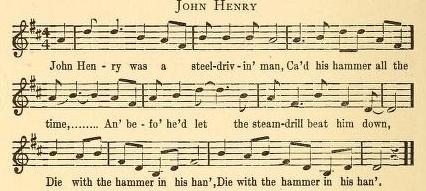

A few of the tunes presented in the following pages are the older Negro secular tunes. Stagolee and Railroad Bill are rarely heard now, but they were common twenty years ago, and their music is included in the present collection for whatever its preservation may be worth. The words of Stagolee, Railroad Bill and She Asked Me in de Parlor are reprinted in full from The Negro and His Songs, but only the first stanzas of the other songs are given, since the rest of the words can be found in the preceding chapters of the present volume. The songs in every case are written in the key in which they were sung.

Stagolee

Stagolee, Stagolee, what's dat in yo' grip?

"Nothin' but my Sunday clothes, I'm gonna to take a trip,"

Oh, dat man, bad man, Stagolee done come.

Stagolee, Stagolee, where you been so long?

I been out on de battle fiel' shootin' an' havin' fun.

Oh, dat man, etc.

Stagolee was a bully man, an' ev'ybody knowed

When dey seed Stagolee comin' to give Stagolee de road.

Stagolee started out, he give his wife his han';

"Goodby, darlin', I'm goin' to kill a man."

Stagolee killed a man an' laid him on de flo',

What's dat he kill him wid? Dat same ol' fohty-fo'.

Stagolee killed man an' laid him on his side,

What's dat he kill him wid? Dat same ol' fohty-five.

Out of house an' down de street Stagolee did run,

In his hand he held a great big smok'n' gun.

Stagolee, Stagolee, I'll tell you what I'll do;

If you'll git me out'n dis trouble I'll do as much for you.

Ain't it a pity, ain't it a shame?

Stagolee was shot, but he don't want no name.

Stagolee, Stagolee, look what you done done:

Killed de best ol' citerzen, now you'll have to be hung.

Stagolee cried to de jury, "Please don't take my life,

I have only three little children an' one little lovin' wife."

Railroad Bill

Railroad Bill mighty bad man,

Shoot dem lights out o' de brakeman's han',

Was lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

Railroad Bill mighty bad man,

Shoot the lamps all off de stan',

An' it's lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

First on table, next on wall;

01' corn whiskey cause of it all,

It's lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

01' McMillan had a special train;

When he got there was shower of rain,

Wus lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

Ev'ybody tol' him he better turn back;

Railroad Bill wus goin' down track,

An' it's lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

Well, the policemen all dressed in blue,

Comin' down sidewalk two by two,

Wus lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

Railroad Bill had no wife,

Always lookin' fer somebody's life,

An' it's lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

Railroad Bill was the worst ol' coon:

Killed McMillan by de light o' de moon,

It's lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

0l' Culpepper went up on number five,

Goin' bring him back, dead or alive,

Wus lookin' fer Railroad Bill.

She Asked Me in de Parlor

Well, she ask me in her parlor

An' she cooled me wid her fan,

An' she whispered to her mother,

"O Ma, I love that dark-eyed man."

Well, I ask her mother for her

An' she said she was too young.

Lawd, I wished I never had seen her

An' I wished she'd never been born.

Well, I led her to de altar,

An' de preacher give his comman',

An' she swore by God that made her

That she never love another man.

John Henry

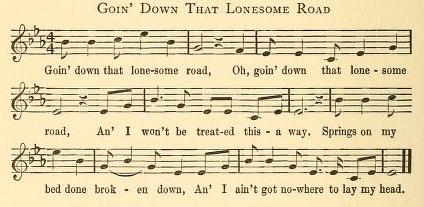

Goin' Down That Lonesome Road

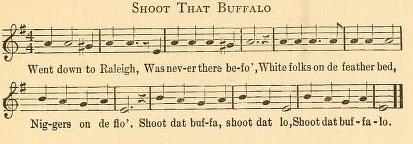

Shoot That Buffalo

I Got a Rainbow

I Don't Want No Trouble Wid de Walker

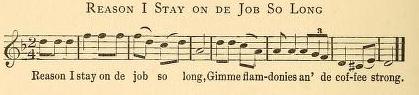

Reason I Stay on de Job So Long

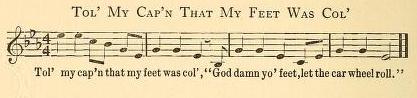

Tol' My Cap'n That My Feet Was Col'

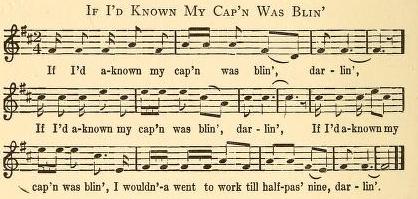

If I'd Known My Cap'n Was Blin'

[1] For a discussion of the recent collections of Negro songs, see Guy B. Johnson, "Some Recent Contributions to the Study of American Negro Songs," Social Forces, June, 1926.

[2] The nearest approach ever made to accurate recording of such songs is found in the work of the late Natalie Curtis Burlin. See her Negro Folk Songs, Hampton Series, vols. Ill and IV.

[3] For other discussions of work songs, see Natalie Curtis Burlin, Negro Folk Songs, vols. III and IV; Dorothy Scarborough, On the Trail of Negro Folk Songs, chapter VIII; R. Emmet Kennedy, Mellows; Odum and Johnson, The Negro and His Songs, chapter VIII.