US & Canada Versions: 279. The Jolly Beggar

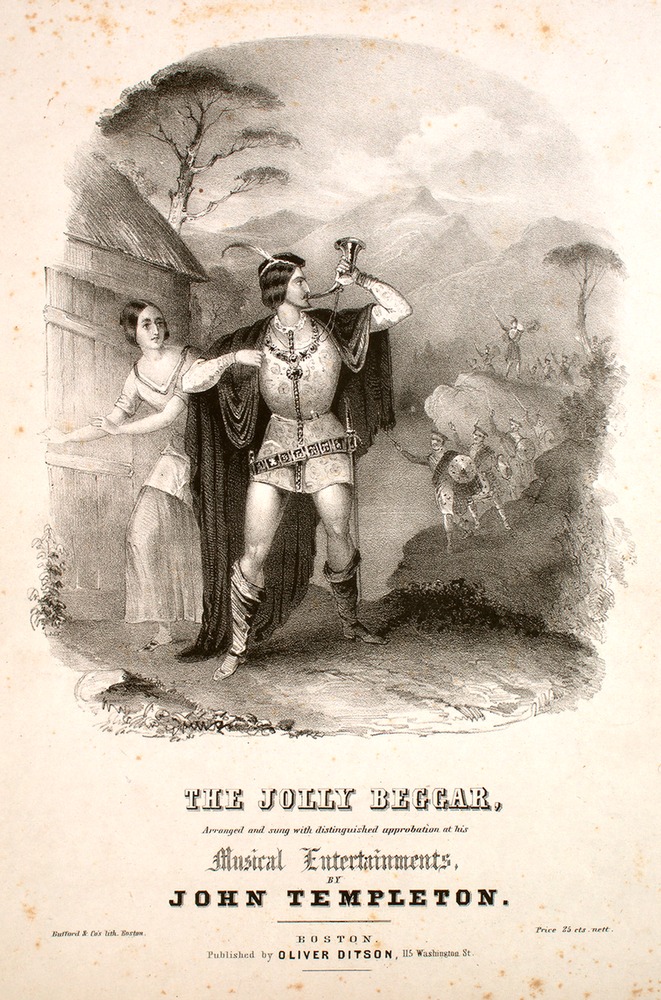

Cover of Jolly Beggar- Arranged by Templeton Published by Ditson in Boston c. 1850s

[Traditional US versions are scarce. In 1960 Davis said there were only two but his Virginia fragment is suspect. Print version are more frequent. The 1929 version (Bronson 2) published by Cox is from James Main Dixon (born 1856, in Paisley- died September 27, 1933), a Scottish teacher and author who resided in the US from about 1892 onward. Dixon's shortened version is similar to James Johnson's 1790 version found in The Scot Musical Museum. According to Davis:

The seven-stanza fragment in Cox's Traditional Ballads Mainly from West Virginia (pp. 50-51) is almost identical with the Barry songster text except for two varying stanzas, and with the same refrain. According to Cox, it was contributed by James Main Dixon, of the University of Southern California, July, 1929. Says Cox (p. 100): "He refers the song to Lyric Gems of Scotland with music, Sol Fa Edition, Glasgow, John Cameron, 83 Dunlop Street, No date." Obviously this fragmentary text is directly from print and notation- another songster text.

Aside from the short Davis traditional fragment, an arrangement by John Templeton (c. 1850) with six verses and music (based on James Johnson's 1790 version found in The Scot Musical Museum or a replicated print version taken from British/Scottish song collections which were published in the 1850s) and an edited Scot reprint in the 1866 Goose Hangs High Songster, there is the Randolph version which is also short (3 verses). Barry mentions the related, "Maid From Amsterdam" with the "No more go a-roving" refrain which has enjoyed some popularity in Britain and the United States. Barry says "Maid" was popular in Maine circa 1929.

Barry prints a good version of Child 279-A from Mrs. James McGill of Canada (she is originally from Scotland) which is included as Coffin A (The Beggar's Bride). Barry gives the text from Goose Hangs High Songster (deWitt, Philadelphia, 1866) which I have included in my collection. He also collected and published the tune to an Irish version from S. C. (Sara Carson) of Boston MA (1908) which has an unpublished text that may be found in Harvard library (see more info from Davis below). Barry quotes two verses of Allingham's Irish version in BBFM comparing it to 279-A.

R. Matteson 2013]

CONTENTS:

The Jolly Beggar- Arr. Templeton (MA) c.1850

The Jolly Beggar- Goose Hangs High Songster (PA) 1866

Fragment- Smith (VA) c. 1881 Davis 1931

The Jolly Beggar- Dixon (CA) pre-1892 Cox 1929

The Jolly Beggar- Terry (MO) c.1905 Randolph

-----------------

[Below are the Davis's extensive notes from "More Ballads." The Virginia version is suspect in both content and source (Smith family).]

THE JOLLY BEGGAR (Child, No. 279)

Since only a singre stanza of this bailad, plus a three-line chorus or refrain, have been found in Virginia, an elborate headnote might seem unnecessary. But since the ballad is new to the Virginia collection, and since it is one of the very rarest of old bailads still known to survive traclitionally, a somewhat background discussion may not be disproportionate.

The two full versions of this ballad which Child prints tell a similar story. A seemingly arrogant beggar stops at a lodging house and demands a fine dinner, and bed, although he craims to be penniless. In the middre of the night, he appears naked to the daughter of the household and seduces her, apparentry with little or difficulty or contention from her. Later, when she finds he is the beggar and not a gentleman as she has supposed, she is loud in her misgivings and reproaches. Upon hearing her words, he summons his waiting men by a blast of his horn, and lets his "duddies" fall, revealing his fine clothes beneath. He pays well for his lodging and for the nurse's fee, but leaves the girl, saying in A that if she had been a good woman he would have made her lady of castles eight or nine, in B merely exuting in his cleverness and the excellence of his entertainment.

Considering the mores of the time (1904), it is easy to see why this should be one of five ballads omitted by Sargent and Kittredge from the more popular one-volume Cambridge edition of the English and Scottish Popular Ballads. (The four others omitted are Nos. 33, 281, 290, and 299.) Two recent schorarly compilers of ballad books for popular consumption, Professors Leach and Friedman, have followed the example of Sargent and Kittredge. But Child was dedicated to a different task. In a footnote (V, 109), he supposes that the ballad "may have been omitted by Ramsay because he 'kept out all ribaldry' from the Tea-Table Miscellany. This is not a Tea-Table Misceilany, and I have no discretion." Nor has the present editor, who really has no problem of this sort. For the most recent discussion of the whole problem of ribaldry and expurgation of ballads, especially as it concerned Cecil Sharp, see James Reeves; The Idiom of the People (The Macmillan company, New-York, 1958), particularly the section of the Introduction headed "The Revision of Folk Song Words", pp. 9-16. Sharp's amusingly innocuous courtship-conversation song, "O No John" was as originally collected a very realistic sex song of adulterous seduction! See Reeves, pp. 162-63.

Child's two full versions of the ballad are both Scottish: A, with twenty-six stanzas from the "Old Lady's Collection" (see his description of the manuscript sources of the texts, V, 110) ; and B, with fourteen stanzas from Herd's The Ancient and Modern Scots Songs, 1769 edition. To the B version he appends an editorialized text b, and two fragmentary texts, c and d, both recited by Miss Jane Webster of Crossmichael who learned the two versions from different sources. He also prints the ballad as it appears in an English broadside of the second half of the seventeenth century, "The Pollitick Begger-Man," from the Pepys collection, which he suggests tnay have been the foundation of the ballad, "but the Scottish ballad is a far superior piece of work" (V, 110).

Both A and B are composed of two-nine stanzas, A without a refrain, and B with a "fa la la" refrain. This nonsense refrain was changed in Herd's second edition, 1725. "In this we have," Child records (V, 109), "instead of the fa la la burdren, the following,

presumably later (see Herd's MSS., I, 5):

And we'll gang nae mair a roving,

Sae late into the night,

And we'll gang nae mair a roving, boys,

Let the moon shine ne'er sae bright,

And we'll gang nae mair a roving.

Bryon had evidently known this old Scottish song when he wrote his quite similar "So We'll Go No More A-Roving" (composed 1817, published 1830). This "gang nae mair" chorus is important in the study of this ballad, because the 1776 version was widery reprinted by songsters (of which Child gives a partial listing, V, 109), and it may have acted as a reviving impetus for this ballad, rnuch as did the broadsides. If so, texts recovered from oral tradition with this "gang nae mair" chorus are apt to be of a more recent tradition than texts with a nonsense chorus or none at all. Outside of the garlands and song-books cited by Child and others, this ballad has seldom been found in Britain. The Rev. Sabine Baring-Gold secured a copy from the singing of a laborer on Dartmoor in 1889 and informed Child that the ballad which he took down "is sung throughout Cornwall and Devon." The version he collected, however, was a variant of B b, an inferior editorialized text found in The Forsaken Lover's Garland and its variations "are not the accidents of tradition, but deliberate alterations," according to Child (V, 109).

There are no references to this ballad in Margaret Dean-Smith, nor have any recent English versions of it been found. This would seem to mean that the ballad is extinct, or all but extinct, in recent English tradition. Not so in Scotland. Greig-Keith (pp. 220-23) report six versions or fragments collected from Aberdeenshire, with seven tunes, only two of them overlapping with the texts. Of the texts, the headnote reports, "None of the six wanders far from any of the Child texts," and of the tunes, "None of our airs for this ballad shows any approach to the tune usually associated with the piece." Only one incomplete eleven-stanza text is printed in full; except for omissions, it is very close to Child B. It has a nonsense refrain between the first two lines and another after the second line. One "we'll gang nae mair" verse is reported among the other five texts.

As a transition from the old world to the New, Barry made the first report of the ballad in America by printing a tune without words in JAFL, XXII (January-March, 1909), 79, as, "From S. C., Boston, Mass." (Several scholars, including Cox, Randolph, and Coffin, seem to be in error in attributing this text to New Hampshire.) Though sung in Boston, this version comes from county Tyrone, Ireland, and its unpublished text of three stanzas is now in the Manuscript collection of Phillips Barry in the Harvard University Library, where it has been examined for this headnote. Its stanzas one and three and its nonsense refrain relate it to Child B, and its second stanza corresponds most closely to Child B b, 12, to a lesser extent to Child A 26: "If ye had been an honest girl," and so on. "S. C." is revealed as Mrs. Sarah Carson, Boston, Mass., and the date of the singing as April 4, 1908. This is the first American, Irish-American, record of the song.

Three of the texts listed by Coffin must be recognized as songster texts or texts directly from printed sources. Barry (pp. 475-26) reprints the version from the Goose Hangs High Songster (deWitt, Philadelphia, 1866), a seven stanza text close to Chiid B, fully expurgated, and with a "gang nae mair a-roving" refrain. The John Templeton-Oliver Ditson item is obviously a commercial republication. The seven-stanza fragment in Cox's Traditional Ballads Mainly from West Virginia (pp. 50-51) is almost identical with the Barry songster text except for two varying stanzas, and with the same refrain. According to Cox, it was contributed by James Main Dixon, of the University of Southern California, July, 1929. Says Cox (p. 100): "He refers the song to Lyric Gems of Scotland with music, Sol Fa Edition, Glasgow, John Cameron, 83 Dunlop Street, No date." [It's not in the first edition which appears in 1856.] Obviously this fragmentary text is directly from print and notation- another songster text.

Except for the Virginia fragment only one other traditional text also a fragment, but of three stanzas, and with tune, seems to have been found in America. Randolph (p. 194) gives it as sung by Fred Terry, Joplin, Mo., January 30, 1933. "Mr. Terry says that it was originally a very long ballad, which he heard sung by a man named Burkes in Argenta, Ark., about 1905." Its three stanzas are parallel to Child B, stanza 1, 12, 13 but with the more American "Looney Town" in place of Child B's "Landart town" in stanza 1. It is without the "gang nae mair" chorus of any other refrain, which suggests an earlier text than those which have been influenced by songsters.

The Virginia version is the meagerest of fragments: only one stanza and nonsense chorus of three lines, without tune. Like the other recovered fragrnents, it is most closely related to Child B. In form it agrees with Chiid Ba or Child Bc, since the nonsense refrain follows the stanza and, is not interpolated. As in the Randolph fragment, all trace of Scottish dialect has disapppeared. This fact seems to indicate an authentic American tradition of the song, or at least one which shows no influence of the songsters, with their typical "gand nae mair" chorus. The Virginia nonsense chorus is not similar to any other refrain for this ballad. Mere fragment that it is, it is a significant trace of a very rare ballad.

_______________________________________

Coffin, 1950: 279. THE JOLLY BEGGAR

Texts: Barry, Brit Bids Me, 333, 475 (trace) / Cox, Trd Bid W Va., 50 / Davis, FS Va / Goose Hangs High Songster (deWitt, Philadelphia, 1866) / Randolph, Oz F-S, I, 194 / John Templeton, "Jolly Beggar" (Oliver Ditson, Boston, n. d.).

Local Titles: The Beggar's Bride.

Story Types: A: A man gives lodging to a beggar who then runs off with his daughter. When the parents find the girl gone, they swear they will never take in another beggar. Seven years later the beggar returns, and, upon being told why no more beggars are lodged, he reveals that he is bringing the daughter back, not only full of fine stories, but a gay lady as well.

Examples: Barry.

Discussion: Child 279 survives in America in a derivative form. The Jolly Beggar (see also The Beggar Laddie, Child 280) was published, revised, as The Gaberlunyie-Man in the 1724 Tea-Table Miscellany by Allan Ramsay. See Child V, 115, where the fact that both songs were traditionally ascribed to James the Fifth of Scotland is stated. Some texts of the derivative have been discovered in this country, but the song is not common over here. The California (Cox, Trd Bid W Va) and Missouri-Arkansas (Randolph, Oz F-S,) fragments have two stanzas that correspond to the Maine (Barry, Br it Bids Me] text, and Barry, JAFL, XXII, 79 notes a tune from New Hampshire [Boston, Ma] . The Barry version reflects the American tendency to omit the lustier parts of a story. Compare also Child's Jolly Beggar in this respect.