English and other Versions: 20. The Cruel Mother

[For detailed notes on the Child texts A-Q see English and Other Versions attached to this page. The O and P texts from the Percy Papers are the oldest versions given by Child. P, a broadside titled The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty, is dated c. 1690 by Kittredge.

According to Cazden and Wiki, Hyder Rollins listed a broadside print dated 1638. Since the title doesn't appear in Rollins' Analytical Index to the Ballad Entries in the Stationers Register, that information seems to be inaccurate. Surely by now, someone would have uncoverd that document.

R. Matteson 2012]

CONTENTS:

1) The Cruel Mother- Herd (Scotland) 1776 Child A

2) Fine Flowers in the Valley- Burns 1792 Child B a.

3) Lady Anne- Scott 1803 Child B b.

4) The Cruel Mother- Motherwell 1827 Child C

5) The Cruel Mother- Beattie 1827 Kinloch; Child D

6) The Cruel Mother- Lyle (Kilbarchan) 1825; Child E

7) The Cruel Mother- Buchan 1828; Child F

8) There Was A Lady- Barry; Notes and Queries 1853; Child G

9) The Cruel Mother- Laird (Kilbarthan) 1825 Child H

10) The Minister's Daughter of New York- 1828; Child I

11) Hey wi' the Rose- Christie 1876 Child I c.

12) The Rose o' Malindie O- Harris c. 1850s Child J a.

13) Lady Margaret- Motherwell c. 1825 Child K

14) Fine Flowers in the Valley- Smith c. 1823 Child L

15) O Mother Dear- Reburn (Ireland) 1860 Child M

16) The Loch o the Loanie- Campbell pre1830 Child N

17) Duke's Daughter- Percy; Late 1600s; Child O

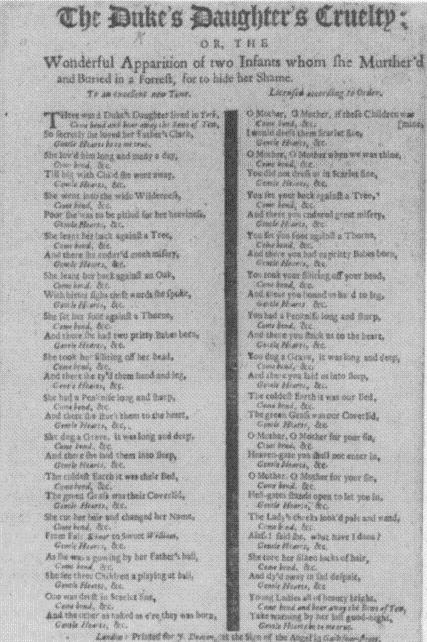

18) The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty- Pepys; c. 1690; Child P This is the broadside ballad The Duke’s Daughter’s Cruelty, or, The Wonderful Apparition of Two Infants whom she Murther’d and Buried in a Forrest, for to hide her shame, printed by J Deacon at the Sign of the Angel in Guiltspur-street, London.

19) The Cruel Mother- Warton; Shropshire 1885 Child Q

20) The Minister's Dochtor o' Newarke- Percy Soc. 1846 (See also Child I)

21) The Sun Shines Fair on Carlisle Wall- Gilpin; 1866

22) The Minister's Dochtor o' Newarke- 1871

23) The Cruel Mother- Russell (Upwey) 1907

24) The Cruel Mother- Case (Dorset) 1907

25) The Cruel Mother- Bowring (Dorset) 1907

26) The Cruel Mother- Hollingsworth (Thaxted) 1911

27) River Sáile- Fergus (Dublin) early-1900s

Old Muvver Lee- Opie (London) pre-1950

Weela Wallia- Clancy Brothers 1965

The Cruel Mither- Higgins (Aberdeen) 1973

____________________

--------SUPPIMENTAL ARTICLES & VERSIONS---------

The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty

Roud 9, Child 20

[A version of this article was published in English Dance and Song Volume 64 part 3; Published here by permission of the current editor, Derek Schofield. This article states, " Of the few Scots versions in Child which mention where the lady's from, one mentions 'Lurk' and another 'New York', both obviously derived from York" which ignores the likely city, Newark.

R. Matteson 2012]

The Cruel Mother is one of our more popular and celebrated ballads, widespread yet not frequently collected in Britain, with most oral versions tending to be fragmentary. It has an impressive pedigree with seemingly little help from print, whereas many of the Child Ballads collected since Child's time can be traced back to printed sources. In fact the most collected ballad of all, Barbara Allen, Roud 54, Child 84, has been constantly in print for at least two centuries, on broadsides and in sheet music form. There appears to be no broadside versions of The Cruel Mother other than the one here shown.

This late 17th century version shows signs of having been tampered with by an amateur poet yet it contains all of the elements found in traditional versions. Almost all of the thirteen versions given in Child's first volume are from Scotland, but plenty of versions have been collected since Child's time in England and America. English versions come from the southern counties and the midlands although the burlesque/children's version is more widespread. This may just be a reflection of the fact that relatively little collecting has been done in the north of England until more recently.

Although there is no evidence to suggest that any of the English versions derive from the broadside, the one major link is the lady's hailing from York, which is common to all English versions that mention a place. Of the few Scots versions in Child which mention where the lady's from, one mentions 'Lurk' and another 'New York', both obviously derived from York.

Danish versions referred to by Child follow the same events pretty closely but cast no light on where the ballad may have originated. We tend to assume that if one of our ballads existed in Scandinavia or elsewhere in Europe then it must have originated there, but it could just as easily have travelled from this country to Europe. Some Danish ballads are actually set in England, although that does not mean they originated here. Often in Danish ballads the word England is used to denote some vague country off to the west.

Child did include the broadside version in his appendix to his second volume: presumably he wasn't aware of it when his first volume was published.

By far the most common refrain for the ballad is the 'All alone and aloney-o … Down by the greenwood side'. The refrain given in the broadside version occurs in no other version, but the last line of the ballad 'Take warning by her last goodnight' is echoed in the second refrain of Child's A version, from the Herd MSS 'Ten thousand times good-night and be wi' thee', the 'last good-night' having the same meaning as another Child Ballad Johnny Armstrong's Last Goodnight, Roud 76, Child 169, i.e., impending death.

The

Duke's Daughter's Cruelty

or the

Wonderful Apparition of two Infants whom she Murther'd

and Buried in a Forrest, for to hide her Shame.

To an excellent new Tune. Licensed according to Order.

There was a Duke's Daughter lived in York

Come bend and bear away the Bows of Yew

So secretly she loved her Father's Clerk,

Gentle Hearts be to me true.

She lov'd him long and many a day,

Till big with Child she went away.

She went into the wide Wilderness,

Poor she was to be pitied for her heaviness.

She leant her back against a Tree,

And there she endur'd much misery.

She leant her back against an Oak,

With bitter sighs these words she spoke.

She set her foot against a Thorne,

And there she had two pritty Babes born.

She took her filliting off her head,

And then she ty'd them hand and leg.

She had a Penknife long and sharp,

And there she stuck them to the heart.

She dug a Grave, it was long and deep,

And there she laid them into sleep.

The coldest Earth it was their Bed,

The green Grass was their Coverlid.

She cut her hair and changed her Name,

From Fair Elinor to Sweet William.

As she was gowing by her Father's hall,

She see three Children aplaying at ball.

One was drest in Scarlet fine,

And the other as naked as e're they was born.

O Mother, O Mother, if these Children was mine,

I would dress them Scarlet fine.

O Mother, O Mother, when we was thine,

You did not dress us in Scarlet fine.

You set your back against a Tree,

And there you endur'd great misery.

You set your foot against a Thorne,

And there you had us pritty Babes born.

You took your filliting off your head,

And there you bound us hand and leg.

You had a Penknife long and sharp,

And there you stuck us to the heart.

You dug a Grave, it was long and deep,

And there you laid us into sleep.

The coldest earth it was our Bed,

The green Grass was our Coverlid.

O Mother, O Mother, for your sin,

Heaven-gate you shall not enter in.

O Mother, O Mother, for your sin,

Hell-gates stands open to let you in.

The Lady's cheeks look'd pale and wand,

Alas! said she, what have I done?

She tore her silken locks of hair,

And dy'd away in sad despair.

Young Ladies, all of beauty bright,

Take warning by her last good-night.

London, Printed for J Deacon at the Sign of the Angel in Guiltspur-street. (c.1684)

(Filliting: a narrow band for encircling the head or binding the hair)

This version reproduced in The Jersey Collection, The Osterley Park Ballads, p150, and The Pepys Ballads Volume 5, p4.

The Cruel Mother Revisisted; a follow-up to Dungheap article 6

Having analysed the majority of the extant texts of Child 20 and closely compared them stanza by stanza I herein present further findings, mainly covering those motifs not found in the Deacon broadside version reprinted in Pepys Vol.5, p.4; Osterley Park Ballads p.150; and Roxburghe Ballads (Ebsworth) Vol.9, part 1, lvi.

First though, further thoughts on the continental analogues described by Child. It is apparent that some American editors of anthologies of the interwar period had not read Child's notes to the ballad thoroughly in that several of them misquote Child claiming that the ballad had been found in Denmark and Germany. Child does state that four versions of the ballad had turned up in Denmark, but not before 1870. He states that the two versions found in Jutland 'approach surprisingly near to Scottish tradition'. However he fails to link this with his statement two pages later that Grundtvig translated and collated several Scottish versions and published two versions in his Engelske og Skotske Folkeviser in the 1840s. It is surprising how quickly literary ballads and translations enter oral tradition, often helped by reprintings in other anthologies. Twenty-five years, in oral tradition, is a long time.

As for the German connection, any similarity between German ballads and The Cruel Mother is rather stretched. As Child states himself 'the resemblance is rather in the general character than in the details': In fact the plot of the German ballads is much closer to Child 21 The Maid and the Palmer as Child acknowledges in a later volume.

In Dungheap 6 I stressed the fact that nearly all versions that have the appropriate introductory stanza follow the broadside in setting it in York, or a derivative of it (New York, Newark, Lurk), but a few versions go further than this and echo the broadside in that the mother is a duke's daughter of York; a single stanza found by Greig (Greig -Duncan Collection, Vol.2, p.31) and a Massachusettes version traced back to the early nineteenth century (Flanders' Ancient Ballads Traditionally Sung in New England Vol.1, p.236, version D). In Child's I version (Buchan) she has become a minister's daughter of New York and in a Scottish version found in Wiltshire she has become a minister's daughter in the North. Kinloch (Child D) is alone in placing her in London and Crawfurd transposes New York into Newark (Crawfurd's Collection, Lyle, 1975, Vol.1, p.36 and Vol.2, p.92).

Stanzas not found in the broadside version appear to have been introduced at a later stage, some developments or extensions of what was already there, but Scottish versions particularly, and about half of the North American versions, end with anything upto six stanzas of the penances found in Child 21 The Maid and the Palmer. None of the English versions contain these stanzas which usually replace the broadside stanzas in which the ghostly babes deny the mother entrance to heaven and condemn her into hell.

Two more stanzas, seemingly lifted directly from the blood-stained hands scene acted out by Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth, are also found in a few widely dispersed versions (not Scottish), (See Williams Folk Songs of the Upper Thames p.295, stanzas 4 and 5; and Child Q from Shropshire Folklore stanza 4). The mother wipes the murder weapon, a penknife, in the sludge or a river then unsuccessfully tries to wash the blood from off her hands. This intrusion also occurs in some versions of the Dublin/Liverpool children's version.

Some versions have introduced the commonplace idea that having disposed of the babes she could then return home a maid, as shown in Child's D version (Kinloch) stanza 6, and the I version (Buchan) stanza 6. In Child 21 the murderess can become a maid again only when she has completed the abovementioned penances.

Often linked into this stanza, though more common on its own, is the unlikely but popular idea of her burying the babes beneath a marble stone, instead of the green grass coverlid of the broadside. The idea that a desperate pregnant girl should go out secretly into the greenwood to kill her babes and then have access to a marble stone rather stretches the imagination, but of such things ballads are made and marble stones are almost synonymous with burials in the ballad world so it is natural that this should have crept in.

In three Scottish versions, Child A (Herd) and B (Johnson/Scott) and Duncan's F version (Greig-Duncan Collection Vol.2, p34, stanza 7) is a stanza in which she asks the babes not to smile at her as it will kill her. As these are the only versions of this it is probable that the other two derive from Herd. This single stanza was expanded by one of the Scottish poets into a ballad all of its own (See Child Vol.1, p.227).

Four American versions name the children as Peter and Paul (Two Maine versions, B and C in Flanders Vol.1, pp.234-5; and a Georgia version B and a North Carolina version L in Sharp and Campbell English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians Vol.1, p.56 and p.62). This is echoed in another literary remake of the plot Lady Anne found in Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border and elsewhere (See Child Vol.1, p.227). A glance at Child's O version (wrongly designated as N) from the Percy papers shows 'Peter and Paul' as likely to be a corruption of 'purple and pall'. Curiously in this version she kills her two pretty babes but then on arriving home sees not two but three babes playing at ball, two clothed and one naked. Presumably the two clothed ones must be hers.

In a few versions, e.g., Child C (Motherwell) and N (Campbell) the everpresent stanzas 'babes, if you were mine, I'd dress you in silks so fine' and the response that they are her children and she had her chance, have spawned repetitious extensions of these ideas, usually 'I'd dress you in silk and wash you in milk' which is a ballad commonplace.

There are other intrusions into the general stock of motifs that only occur in a single version, but as these have not gained a foothold on the tradition I have ignored them. Of course another avenue of study would be the versions of the children's game and street versions of Dublin and Liverpool.

Anyone interested in an analysis of the tunes need go no further than Bronson The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads Vol.1.

Dungbeetle - 13.2.07

------The Minister's Dochtor o' Newarke---From: Early English poetry, ballads, and popular literature: Volume 17 - Page 96

Percy Society - 1846

VII.

The minister's dochter o' Newarke,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

Has fa'en i' luve wi' her father's clerk,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

She courted him sax years and a day,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

At length her fause-luve did her betray,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

She did her doun to the green woods gang,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

To spend awa' a while o' her time,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

She lent her back unto a thorn,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

And she's got her twa bonnie boys born,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

She's ta'en the ribbons frae her hair,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

Boun' their bodies fast and sair,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

She's put them aneath a marble stane.

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

Thinkin' a may to gae her home,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

Leukin' o'er her castle wa',

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

She spied twa bonny boys at the ba' ,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O;

O bonny babies if ye were mine,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

I wou'd feed ye wi' the white bread and wine,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O;

I wou'd feed ye with the ferra cow's milk.

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

An' dress ye i' the finest silk,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

O, cruel mother! when we were thine,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

We saw nane o' your bread and wine,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

We saw nane o' your ferra cow's milk,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

Nor wore we o' your finest silk,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

O, bonny babies can ye tell me,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

What sort o' death for ye I maun dee,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

Yes, cruel mother, we'll tell to thee,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

What sort o' death for us ye maun dee,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

Seven years a fool i' the woods,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

Seven years a fish i' the floods,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

Seven years to be a church bell,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

Seven years a porter i' hell,

Alane by the green burn sidie, 0.

Welcome, welcome, fool i' the wood,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

Welcome, welcome, fish i' the flood,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

Welcome, welcome, to be a church bell,

Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, O;

But heavens keep me out o' hell,

Alane by the green burn sidie, O.

This ballad is on the same subject as the preceding one, and appears to be more ancient. It is well known in Scotland under the title of "The Minister's Daughter of New York" an evident and ludicrous corruption of Newark, the village of Newark on Yarrow being the locality. By "minister" is meant a minstrel, as in Chaucer:—

"A gret host of ministers

With instruments and sounes diverse."

Chaucer's Dreamt, 1. 2132.

By "clerk," the editor is inclined to think, is not meant a person in holy orders, but a student. The term, when so applied by Chaucer, Gower, Douglas, &c. signifies a student at an university, as, "the clerk of Oxenforde"; but our student appears to be only a young man learning "al maner of mynstralcie."

The burden of this ballad is very ancient, and when coupled with the purgatorial nature of the punishment of the heroine, affords a strong presumption of the antiquity of the whole composition. The "lindie" is the lime or lindentree, a tree which figures in the burdens of the old Scalds. The word is derived from an Icelandic verb signifying to bind, bonds or ropes having been formerly made of the bark of that tree. The linden, under the term " lynde" or " linde" often occurs in the old English authors, as in

Chaucer:— "Be ay of chere, as light as lcfe on linde."

Clerke's Tale, 1. 0087.

In the old ballad of " Adam Bell, Clym of the Clouch, and William of Cloudesly," in Percy's Reliques, the "lynde" occurs twice:—

"Thus be these good yemen gon to the wood

And lygbtly as lefe on lynde.''

"Cloudesle walked a lytle beside,

He looked under the grene wood lynde."

The ancient ballad-writers seem to have rung the changes between the expressions " under the lynde," and " under the green-wood tree," both being frequently to be met with in the works of writers of the same age. The reason why, more than any other tree, the linden was so great a favourite with the Scalds, whose compositions our old ballad authors copied, may perhaps be found in the fact of bow-strings having been made from the bark.

The instances in very old ballads of burdens containing the names of trees, shrubs, and flowers, are very numerous, and many examples might be adduced; the oak, the lime or linden, the willow, the mulberry, the rose, the juniper, the rosemary, the birk, the broom, the lily, cfcc.; all of these may be found in different old burdens.

P. 50, v. 3.—In this verse, (the only one where it is so), the rhyme is deficient. The reciter has no doubt made a mistake in the first line, which is not such an one as an old minstrel would have written. There can be little question that the true reading is—

"She did her doun to the green wood linde."

This reading, the word linde, being, after the Scottish manner, pronounced lin\ would no doubt be thought by the writer, a good rhyme with "time."

P. 51, v. 4,—Ferra cow.] A ferra cow is a cow that is not with calf, and therefore, continues to give milk through the winter. Dr. Jamieson supposes the phrase to be derived, (on the Incus a non lucendo principle), from the Belgic vare koe, i.e. a milkless cow; "the original idea being that a cow that did not carry, would, by degrees, lose her milk entirely."

P. 52, v. 3.—A fool.] A fowl. The spelling being in accordance with the pronunciation.

THE CRUEL MOTHER [From: The ballad Minstrelsy of Scotland: romantic and historical]

Various versions of this ballad, more or less varied, have appeared, as under:—

I "A few mutilated stanzas," in Herd's Scottish Songs, vol. it, p. 237, with the refrain of—

"Ota, and alas-a-day! oil, and alas-a-day!

Ten thousand times good night and [joy] be wi' thee."

II. "Fine Flowers in the Valley," Johnson's Musical Musam, vol. iv., p. 331, aa communicated by the poet Burns. The title is taken from the first line of the refrain, the other line being— "And the green leaves they grow rarely."

The lines quoted below by Scott, from memory, are almost identical with stanzas 1, 2, 5, 6, and 7 of this version.

III . "Ladye Anne," in Scott's Minstrelsy, vol . iii., p. 18, and "communicated" to him "by Mr. Charles Kirkpatriek Sharpe of Hoddom, who mentions having copied it from an old magazine. Although it has probably received some modern corrections, the general turn seems to be ancient and corresponds," says Scott, "with that of a fragment, containing the following verses, which I have often heard sung in my childhood:—

"She set her back against a thorn.

And there she haa her young son bom.

'Oh, smile na sae, my bonnie babe!

An ye smile sae sweet, ye'll smile me dead.'

An' when that ladye went to the church,

She spied a naked boy in the porch."

' Oh, bonnie boy, an yo were mine,

I'd clead ye in the silks sae fine.'

'Oh, mother dear, when I was thine,

To me ye were na half sae kind.'"

"Ladye Anne" was reprinted by Buchan, with the addition of one stanza, in his Gleanings of Old Ballads, p. 90. IV. "The Cruel Mother," in Motherwell's Minstrelsy, p. 161. The second and fourth lines, composing the refrain, are respectively—

"Three, three, and three by three;"

and,

"Three, three, and thirty-three."

V. "The Cruel Mother," in Kinloch's Ancient Scottish Ballads, p. 44. The opening line describes "London" as the place of the lady's residence. Mr. Kinloch mentions that '' the Scottish Parliament, in 1690, had recourse to a severe law, which declared that a mother concealing her pregnancy, and not calling in assistance at the birth, should be presumed guilty of murder, if the child were" amissing or found dead. Sir Walter Scott's Heart of Midlothian is chiefly founded on a breach of this law. The refrain of Mr. Kinloch's version is the one here adopted.

VI. "The Minister's Daughter of New York," in Buchan's Ancient Ballads, vol. ii., p. 217; or, "The Minister's Dochter o' Newarke," as the title is given in an improved copy of the same, which appears in Scottish Traditional Versions of Ancient Ballads, Percy Society, vol. xvii., p. 51. The refrain is—

"Hey wi' the rose and the lindie, 0;"

and,

"Alane by the green burn sidie, 0."

VII. "The Cruel Mother," which also appears in Buchan's Ancient Ballads, vot ii., p. 222, and m the Percy Society series, vol. xvii., p. 46. It closes with this stanza—

"She threw hersell ower the castle-wa'—

Edinbro! Edinbro!

8he threw hersell ower the castle-wa'—

Stirling for aye;

She threw hersell ower the castle-wa';

There I wat she got a fa'—

So proper Saint Johnston standsfair upon Tay."

VIII. Smith's Scottish Minstrel, vol. iv., p. 33, contains a still different version under the same title, and with the same refrain as that contained in Johnson's Musical Museum.

Five German and three Wendish ballads of a similar nature are referred to by Professor Child, in English and Scottish Ballads, vol ii., j.. 262.

The annotator of "The Minister's Dochter o' Newarke" (Percy Society series, vol . xvii., p. 96) explains that " by 'minister' is meant a minstrel, as in Chaucer:—

* A grot host of minister*

With instruments and sounes diverse.'

Chaucer's Dreame, l., 2132."

And "by 'clerk,' " he infers that it is not "a person in holy order", but a student or young man learning "al maner of mynstralcie," that meant.

The same writer regards "the village of Newark, on Yarrow," as "the locality" indicated. Mr. Furnivall may, however, feel inclined to claim the heroine and ballad as English, and localize both at Newark, in Nottinghamshire—a noted stage on the road from York to London. Or some zealous American may contend that Mr. Buchan's title is perfectly correct For our own part, with the impartiality and fairness so specially characteristic of Scotsmen, we forbear to dogmatize.

The writer already quoted remarks, that ''the burden of this ballad [version VI. ] is very ancient, and, when coupled with the purgatorial nature of the punishment of the heroine, affords a strong presumption of the antiquity of the whole composition."

Pythagorian, in place of purgatorial, is probably the more correct term.

This feature is peculiar to version VI., which is the one chiefly followed in the text here printed.

1. The minister's dochter of Newarke,

All alone, and alonie,

Has fallen in love with her father's clerk,

Down by the greenwood sae bonnie.

2. She courted him sax years and a day;

At length her false love did her betray.

3. She has ta'en her mantle her about,

And sat her down on an auld tree root.

4 She leant her back unto an aik:

First it bow'd, and syne it brake.

5 She leant her back unto a thorn,

And there she has her twa babes born.

6. "Oh, smile na sae, my babes sae sweet,

Smile na sae, for it gars me greet."

7 She's ta'en the ribbons frae her hair,

And bound their bodies fast and sair.

8 Then she's ta'en ont a little penknife,

And twined each sweet babe of its life.

9 She's honkit a grave baith deep and wide,

And put them in baith side by side.

10 She's cover'd them o'er with a big whin stane,

Thinking to gang like maiden hame.

11 She's gane back to her father's castle hall,

And she seem'd the lealest maid of them all.

12 As she look'd o'er her father's castle wall,

She saw twa pretty babes playing at the ball.

13 "Oh, bonnie babes, if ye were mine,

I wou'd feed and dead ye fair and fine.

14 "I would feed you with the ferra cow's* milk,

And clead you in the finest silk!"

15 "It's oh, cruel mother! when we were thine,

Ye did neither feed nor clead us fine;

16 "But oh, cruel mother! when we were thine,

Ye tied us with ribbons and hempen twine;

17 "And then ta'en out your wee penknife,

And twined us each of our sweet life."

18 "Oh, bonnie babes I can ye tell me

What sort of penance for this I maun dree?"

19 "Yes, cruel mother! we will tell thee

The penance ye for this maun dree:

20 "Seven years a fool in the woods,

Seven years a fish in the floods;

21 "Seven years to be a church bell,

Pealing joy to us, but woe to yoursel';

22 "Seven years a porter to hell,

And then evermair in its torments to dwell.

23 "But we shall dwell in the heavens hie,

While you your penance and torments dree."

24 "Welcome! welcome! fool in the woods,

Welcome! welcome! fish in the floods;

25 "Welcome! welcome! to be a church bell,

But Gude preserve me out of hell!"

* "Fern cow:" a coir not with calf, bat which continues to yield milk.

_____________

THE BONNIE BAIRNS- [From: The book of British ballads - Page 81 by Samuel Carter Hall, Park Benjamin - 1844 ]

This very beautiful ballad may be considered as the composition of Allan Cunningham, who published it in his "Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern;" though he modestly states that he has " ventured to arrange and eke out these old and remarkable verses." Buchan has printed another version, entitled the " Minister's Daughter of New-York," but in the quotation given from it by Mr. Hall we find no local interest, nor any cause for attaching to it this name. Allan Cunningham differs from other annotators in making his children intercede for their cruel mother at the throne of grace, instead of denouncing and consigning her to eternal misery.

The lady she walk'd in yon wild wood,

Aneath the hollin tree,

And she was aware of two bonnie bairns

Were running at her knee.

The tane it pulled a red, red rose,

With a hand as soft as silk;

The other it pull'd a lily pale,

With a hand mair white than milk.

'Now why pull ye the red rose, fair bairns?

And why the white lily?'

O, we sue wi' them at the seat of grace,

For the soul of thee, ladie!'

'O bide wi' me, my twa bonny bairns!

I'll cleid ye rich and fine;

And all for the blaeberries of the wood,

Yese hae white bread and wine.'

She heard a voice, a sweet low voice,

Say, 'Weans, ye tarry long'—

She stretched her hand to the youngest bairn,

'Kiss me before ye gang.'

She sought to take a lily hand,

And kiss a rosie chin—

'O naught sae pure can bide the touch

Of a hand red-wet wi' sin!'

The stars were shooting to and fro,

And wild fire filled the air,

As that lady follow'd thae bonny bairns

For threelang hours and mair.

'O! where dwell ye, my ain sweet bairns!

I'm woe and weary grown!'

'O! lady, we live where woe never is,

In a land to flesh unknown.'

There came a shape which seem'd to her

As a rainbow 'mang the rain:

And sair these sweet babes pled for her,

And they pled and pled in vain.'

And O! and O!' said the youngest babe,

'My mother maun come in:'

'And O! and O!' said the eldest babe,

'Wash her twa hands frae sin.'

'And O! and O!' said the youngest babe,

'She nursed me on her knee;'

'And O! and O!' said the eldest babe,

'She's a mither yet to me.'

'And O! and O! said the babes baith,

'Take her where the waters rin,

And white as the milk of her white breast,

Wash her twa hands frae sin.'

________________

LADY ANN from Cunningham, Songs of Scotland, I, 340, 1825 (Reprinted from Scott 1803).

Fair lady Ann walked from her bower,

Down by the greenwood side,

The sweet flowers sprang, and wild birds sang,

The simmer was in pride.

Among the flowers that lady went,

As white as was the swan;

And she thought on her love and sighed,

The gentle lady Ann.

Out of the wood came three bonnie boys,

As naked as they were born,

And they did sing and play at the ba',

Beneath a milk-white thorn.

A seven lang years would I stand here,

All noon, and night, and dawn,

And all for one of thae bonnie boys,

Quo' gentle lady Ann.

Then up and spake the eldest boy:

Now listen, thou fair ladie—

O we lay a' at ae milk-white breast,

And nursed were on ae knee;

Ae sweet lip smiled on us as we smiled,

And there was a snaw-white han',

As gentle and kin', and fair as thine,

That watched us, lady Ann.

O come to me, thou lily-white boy,

The bonniest of the three !

O come, O come, thou lily-white boy,

My little bower-boy to be !

I'll deed thee all in silk and gold,

And nurse thee on my knee—

Oh mother, oh mother, when I was thine,

Sic love I couldna see.

I found this song imperfect, and I know not that either to supply or discover the concluding verses would add much to the interest of the story. The death of the children is imputed to a false nurse, in an older copy published in the Minstrelsy; but one of the verses accuses the lady herself, and the traditional fragments quoted by Sir Walter seem to countenance the charge. I remember a verse, and but a verse, of an old ballad which records a horrible instance of barbarity. A lady was in a condition like that of many ladies who figure in ballad and romance:

She set her back against a thorn,

And there she has her young son born:

O smile na sae, my bonnie babe!

An ye smile sae sweet, ye'll smile me dead.

At this moment a hunter came—one whose suit the lady had long rejected with scorn—the brother of her lover:

He took the babe on his spear point,

And threw it Upon a thorn:

Let the wind blow east, the wind blow west,

The cradle will rock alone.

It is as well to let such narratives perish, and I am glad I remember no more of it. I have some suspicion that the fine old song of Lady Mary Ann had once a meaning much less reputable for the lady than it has at present: the commencing lines have an older air than the remainder of the song.