DRAMAS AND PORTRAITS

[This chapter alone has had a big impact on American music. The Kingston Trio released the calypso song John B. Sails based on Sandburg's arrangement in 1958. Then the Beach Boys covered the Kington Trio's version, changing the name to "Sloop John B." and also a few lyrics on their 1960 album, Pet Sounds.

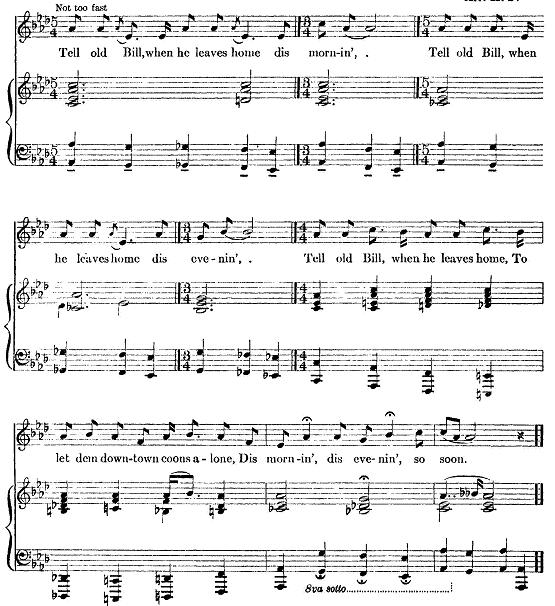

The early version of Dis Morning, Dis Evening, So Soon is known as "Tell Old Bill" was collected in the early 1920's in St. Louis and was the first version of this song printed with music. It was collected earlier by Howard Odum (1911) and others.

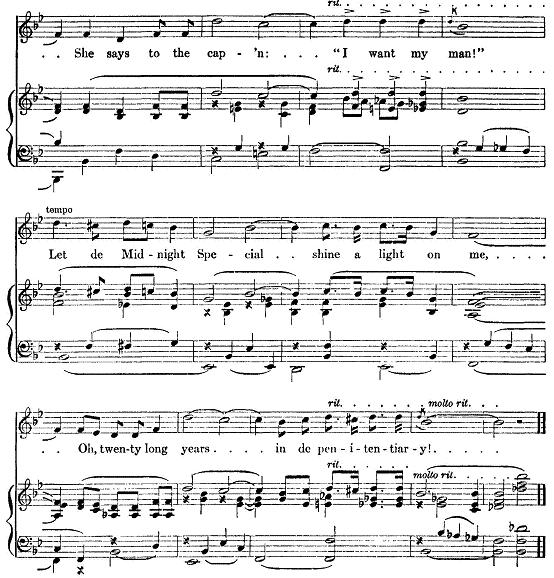

The other well-known song in this chapter first published by Sandburg is the "Midnight Special," a song popularized by Leadbelly who first recorded it in 1934. It has been recorded by many groups including Creedence Clearwater Revival and was the theme song for "The Midnight Special" a TV series in the 1970s hosted by Wolfman Jack.]

HARMONIZATION BY

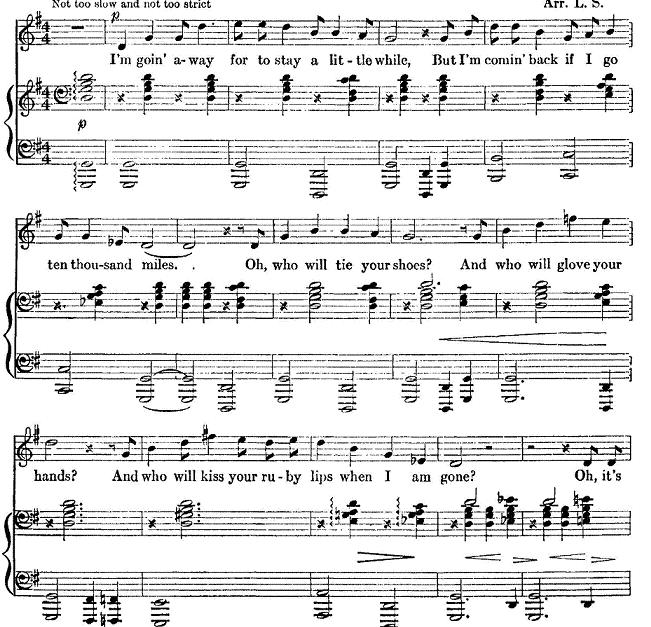

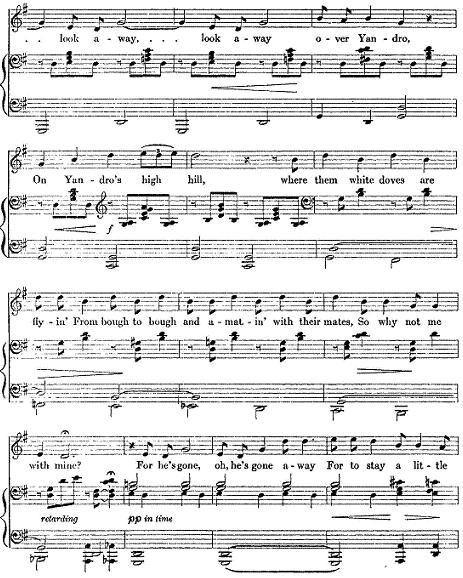

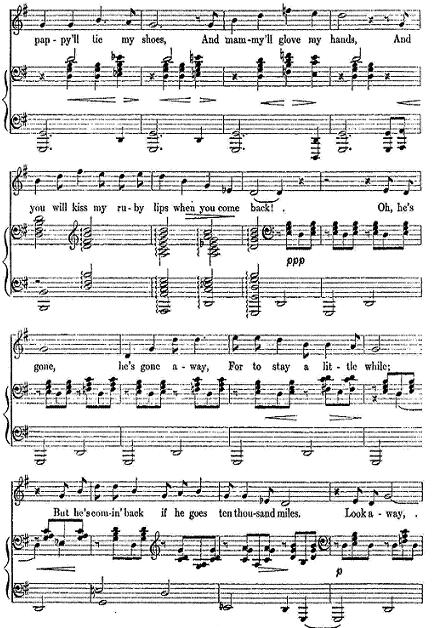

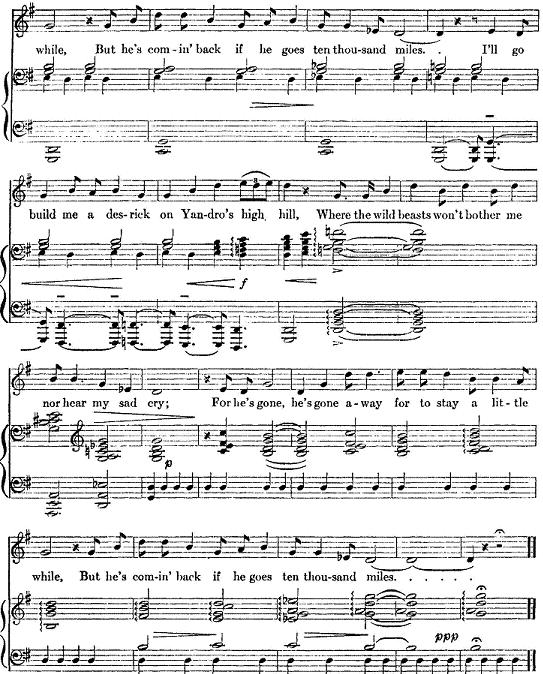

HE'S GONE AWAY Leo Sowerby

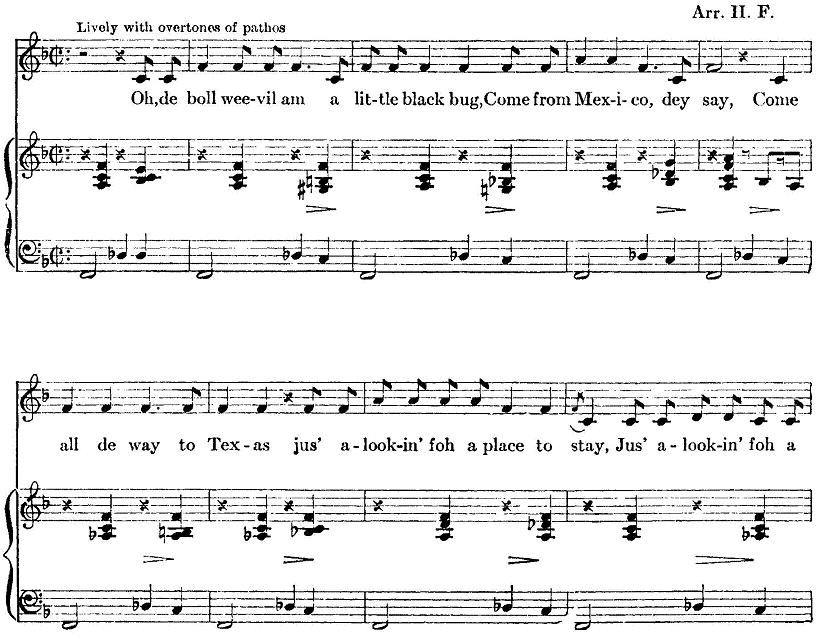

BOLL WEEVIL SONG Hazel Felman

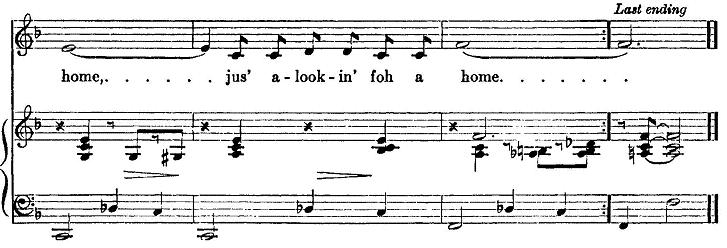

MOANISH LADY! Henry Francis Parks

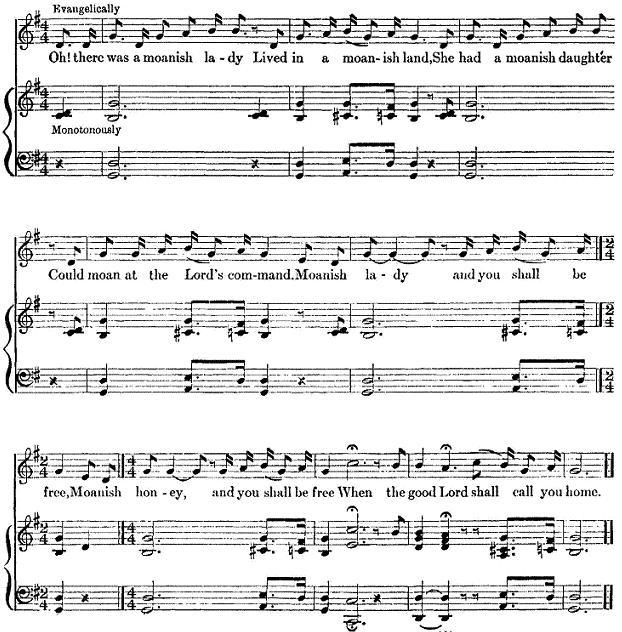

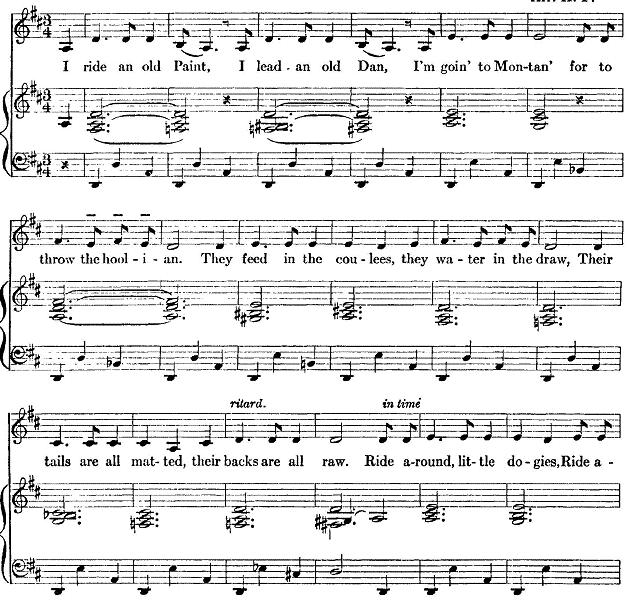

I RIDE AN OLD PAINT Hazel Felman

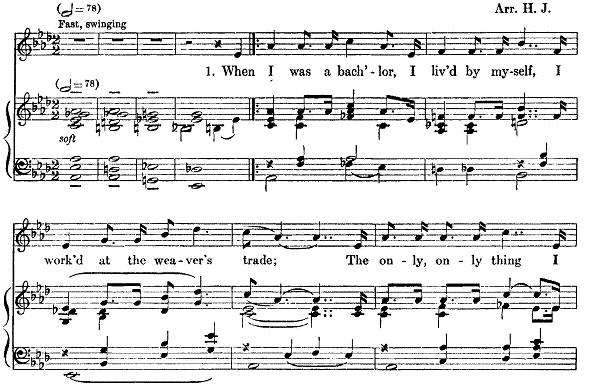

FOGGY, FOGGY DEW Henry Joslyn

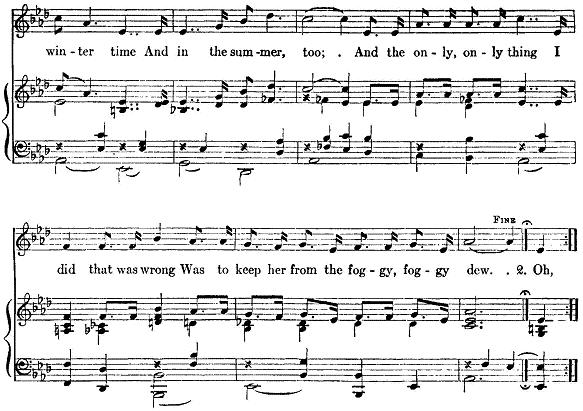

WAILLIE, WAILLIE! Henry Joslyn

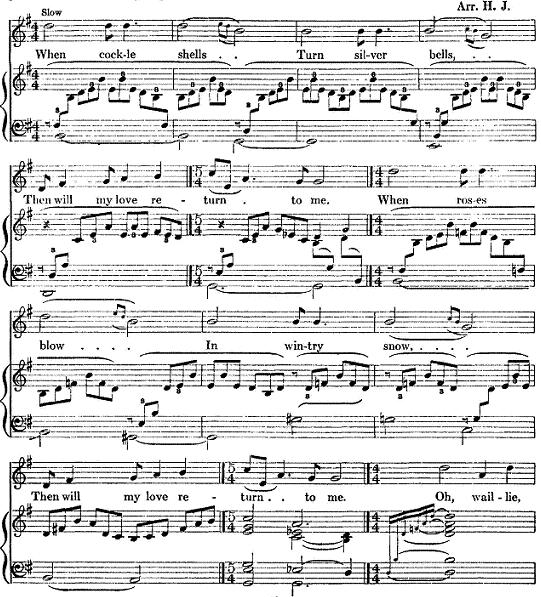

DIS MORNIN', DIS EVENIN', SO SOON Hazel Felman

OH, BURY ME NOT ON THE LONE PRAIRIE Hazel Felman

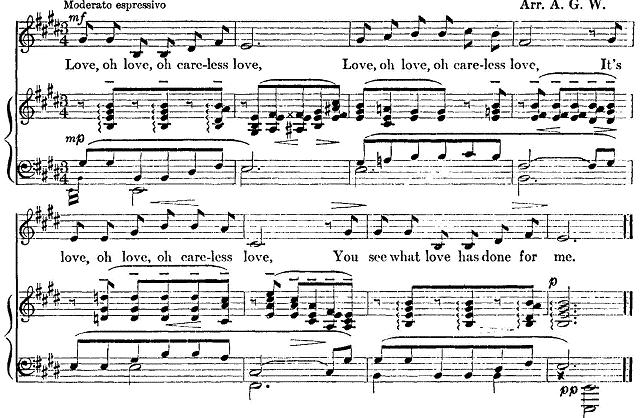

CARELESS LOVE Alfred G. Wathall

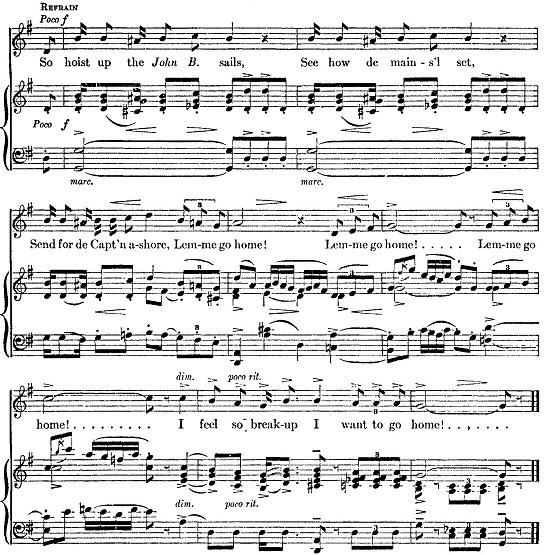

THE JOHN B. SAILS Alfred G. Wathall

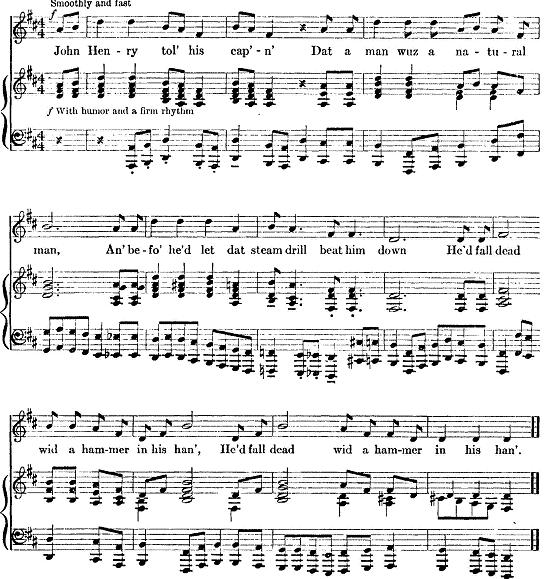

JOHN HENRY Thorvald Otterstrom

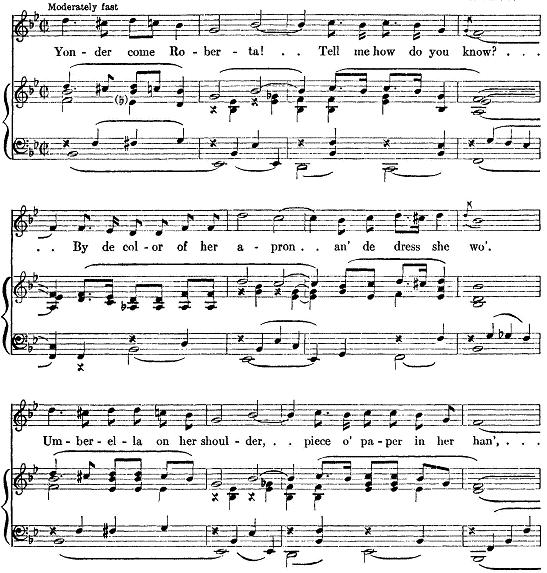

MIDNIGHT SPECIAL Henry Joslyn

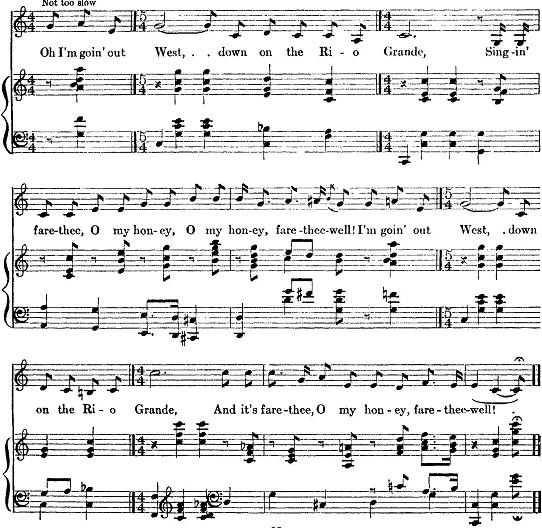

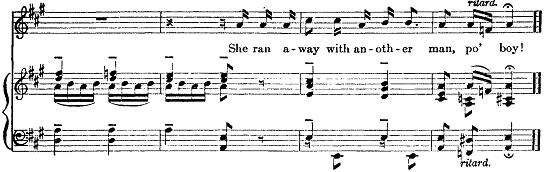

ALICE B. Alfred G. Wathall

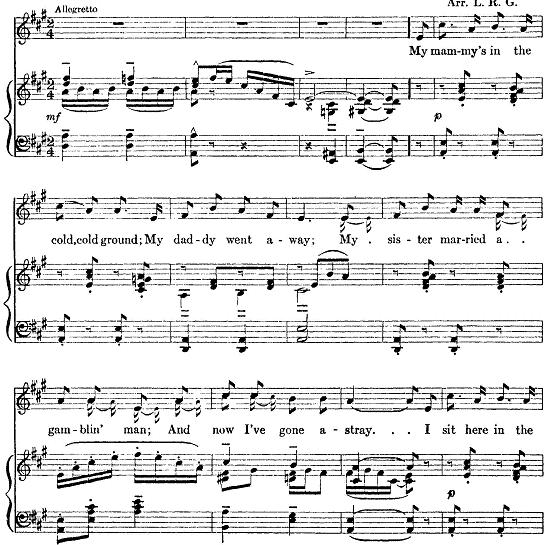

PO' BOY Lillian Rosedale Goodman

The world grows more majestic but man diminishes. Why is this? We carry within us greater things than the Greeks, but we ourselves are smaller. It is a strange result. . . . The whole secret of remaining young in spite of years, and even of gray hairs, is to cherish enthusiasm in one's self by poetry, by contemplation, by charity. . . . The modern haunters of Parnassus carve urns of agate and of onyx; but inside the urns what is there? Ashes. Their work lacks feeling, seriousness, sincerity, and pathos in a word, soul and moral life. I cannot bring myself to sympathize with such a way of understanding poetry. The talent shown is astonishing, but stuff and matter are wanting. It is an effort of the imagination to stand alone a substitute for everything else. We find metaphors, rhymes, music, color, but not man, not humanity. Poetry of this factitious kind may beguile one at twenty, but what can one make of it at fifty? It reminds me of Pergamos, Alexandria, of all the epochs of decadence when beauty of form hid poverty of thought and exhaustion of feeling. I strongly share the repugnance which this poetical school arouses in simple people. It is as though it only cared to please the world-worn, the over-subtle, the corrupted, while it ignores all normal healthy life, virtuous habits, pure affections, steady labor, honesty, and duty. It is an affectation, and because it is an affectation the school is struck with sterility. The reader desires in the poet something better than a juggler in rhyme, or a conjurer in verse; he looks to find in him a painter of life, a being who thinks, loves, and has a conscience, who feels passion and repentance. FREDERICK AMIEL

HE'S GONE AWAY

This is an arrangement from a song heard by Charles Rockwood of Geneva, Illinois, during a two-year residence in a mountain valley of North Carolina. It stages its own little drama and characters. The mountain called Yandro was the high one of this valley. A "desrick," Mr. Rockwood was told, is a word for our shack or shanty. The song is of British origin, marked with mountaineer and southern negro influences. Other mountain places in the southern states have their song about going away ten thousand miles; this one weaves in the exceptional theme of the white doves flying from bough to bough and mating, "so why not me with mine?" Mr. Sowerby was lighted with a rich enthusiasm about this song and has met its shaded tones with an accompaniment that travels in fine companionship with the singer.

HE'S GONE AWAY

I'm goin' away for to stay a little while,

But I'm comin' back if I go ten thousand miles.

Oh, who will tie your shoes?

And who will glove your hands?

And who will kiss your ruby lips when I am gone?

Oh, it's pappy'll tie my shoes,

And mammy'll glove my hands,

And you will kiss my ruby lips when you come back!

Oh, he's gone, he's gone away,

For to stay a little while;

But he's comin' back if he goes ten thousand miles.

Look away, look away, look away over Yandro,

On Yandro's high hill, where them white doves are flyin'

From bough to bough and a-matin' with their mates,

So why not me with mine?

For he's gone, oh he's gone away

For to stay a little while,

But he's comin' back if he goes ten thousand miles.

I'll go build me a derrick on Yandro's high hill,

Where the wild beasts won't bother me nor hear my sad cry;

For he's gone, he's gone away for to stay a little while,

But he's comin' back if he goes ten thousand miles.

BOLL WEEVIL SONG

A boll weevil couple, arriving in a cotton field in the springtime, will have, by the end of summer, more than twelve million descendants to carry on the family traditions. So it is estimated. They are a species of creatures among whom there is no talk at all about "the first families." The billion dollar devastations of this little eater of cotton crops are of America's traditions of tragedy. J. Russell Smith, the geographer, says the economic loss caused by the boll weevil equals in amount that of the four year war in the 'sixties. John Lomax first sang this for the present writer, and of four different airs and sets of words the Lomax version is the most important; the other boll weevil songs are worth printing, however, for artistic and scientific purposes. I have known this song for eight years, since the year John Lomax and his family lived in Indian Hill, Illinois, and it never loses its strange overtones, with its smiling commentary on the bug that baffles the wit of man, with its whimsical point that while the boll weevil can make a home anywhere the negro, son of man, hath not where to lay his head, and with its intimation, perhaps, that in our mortal life neither the individual human creature, nor the big human family shall ever find a lasting home on the earth. Elements, weather, crop gambling, fate, Lady Luck, flit in the backgrounds. It is a paradoxical blend of moods: quickstep and dirge, hilarious defiance and bowed resignation.

BOLL WEEVIL SONG

1. Oh, de boll weevil am a little black bug,

Come from Mexico, dey say,

Come all de way to Texas, jus' a-lookin' foh a place to stay,

Jus' a-lookin' foh a home, jus' a-lookin' foh a home.

2. De first time I seen de boll weevil,

He was a-settin' on de square.

De next time I seen de boll weevil, he had all of his family dere.

Jus' a-lookin' foh a home, jus' a-lookin' foh a home.

3 De farmer say to de weevil:

"What make yo' head so red?"

De weevil say to de farmer, *' It's a wondah I ain't dead,

A-lookin' foh a home, jus' a-lookin' foh a home."

4. De farmer take de boll weevil,

An' he put him in de hot san'.

De weevil say: " Dis is mighty hot, but I'll stan' it like a man,

Dis'll be my home, it'll be my home."

5. De fanner take de boll weevil,

An' he put him in a lump of ice;

De boll weevil say to de farmer: "Dis is mighty cool and nice,

It'll be my home, dis'll be my home."

6. De farmer take de boll weevil,

An' he put him in de fire.

De boll weevil say to de farmer: "Here I are, here I are,

Dis'll be my home, dis'll be my home."

7. De boll weevil say to de farmer:

"You better leave me alone;

I done eat all yo' cotton, now I'm goin' to start on yo' corn,

I'll have a home, I'll have a home."

8. De merchant got half de cotton,

De boll weevil got de res'.

Didn't leave de farmer's wife but one old cotton dress,

An' it's full of holes, it's full of holes.

9. De farmer say to de merchant:

"We's in an awful fix;

De boll weevil et all de cotton up an* lef ' us only sticks,

We's got no home, we's got no home."

10. De farmer say to de merchant:

"We ain't made but only one bale,

And befoh we'll give yo' dat one we'll fight and go to jail,

We'll have a home, we'll have a home."

11. De cap'n say to de missus:

" What d' you t'ink o' dat?

De boll weevil done make a nes' in my bes' Sunday hat,

Goin' to have a home, goin' to have a home."

12. An' if anybody should ax you

Who it was dat make dis song,

Jus' tell 'em 'twas a big buck niggah wid a paih o' blue duckin's on.

Am' got no home, ain' got no home.

MOANISH LADY!

This offshoot of the spiritual, "Mourner, You Shall be Free," has been widely known for many years among barber shop harmonizers. The other stanzas of the barber shop version, however, are so lackadaisical that they don't do justice to the stately cadence of that solemn promise that when the good Lord shall call you home you shall be free. Any one requiring foolish verses for this air can easily improvise as silly ones as have been left out here. The music is too superbly serious to have cheap lines.

I RIDE AN OLD PAINT

This arrangement is from a song made known by Margaret Larkin of Las Vegas, New Mexico, who intones her own poems or sings cowboy and Mexican songs to a skilled guitar strumming, and by Linn Riggs, poet and playwright, of Oklahoma in particular and the Southwest in general. The song came to them at Santa Fe from a buckaroo who was last heard of as heading for the Border with friends in both Tucson and El Paso. The song smells of saddle leather, sketches ponies and landscapes, and varies in theme from a realistic presentation of the drab Bill Jones and his violent wife to an ethereal prayer and a cry of phantom tone. There is rich poetry in the image of the rider so loving a horse he begs when he dies his bones shall be tied to his horse and the two of them sent wandering with their faces turned west.

I RIDE AN OLD PAINT

1. I ride an old Paint, I lead an old Dan,

I'm goin' to Montan' for to throw the hoolian.

They feed in the coulees, they water in the draw,

Their tails are all matted, their backs are all raw.

Ride around, little dogies,

Ride around them slow,

For the fiery and snuffy are a-rarin' to go.

2. Old Bill Jones had two daughters and a song,

One went to Denver and the other went wrong.

His wife she died in a poolroom fight,

Still he sings from mornin' till night.

Ride around, little dogies,

Ride around them slow,

For the fiery and snuffy are a-rarin ' to go.

3. Oh, when I die, take my saddle from the wall,

Put it on my pony, lead him out of his stall.

Tie my bones to his back, turn our faces to the West,

And we'll ride the prairie that we love the best.

Ride around, little dogies,

Ride around them slow,

For the fiery and snuffy are a-rarin' to go.

FOGGY, FOGGY DEW

This arrangement is from a song rather widely known, which I heard first from Arthur Sutherland and his bold buccaneers at the Eclectic Club of Wesleyan University. A middle verse is censored from this version as being out of key and probably an interpolation. At least, it is what they call apocryphal and of the twilight zone. Observers as diverse as Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, Arthur T. Vance and D. W. Griffith say this song is a great condensed novel of real life. After hearing it sung with a guitar at Schlogl's one evening in Chicago, D. W. Griffith telegraphed two days later from New York to Lloyd Lewis in Chicago, "Send verses Foggy Dew stop tune haunts me but am not sure of words stop please do this as I am haunted by the song."

FOGGY, FOGGY DEW

1. When I was a bach 'lor, I lived by myself,

I worked at the weaver's trade;

The only, only thing I did that was wrong

Was to woo a fair young maid.

I wooed her in the winter-time

And in the summer, too;

And the only, only thing I did that was wrong,

Was to keep her from the foggy, foggy dew.

2 Oh, I am a bach'lor, I live with my son;

We work at the weaver's trade;

And ev'ry single time I look into his eyes

He reminds me of the fair young maid.

He reminds me of the winter-time

And of the summer too;

And the many, many times that I held her in my arms,

Just to keep her from the foggy, foggy dew.

WAILLIE, WAILLIE!

An arrangement of an old-time British piece as made known by Daniel Read and Isadora Bennett Read of Chicago, Illinois, and Columbia, South Carolina. Its stately diction might be compared to certain laced ladies and ruffled gentlemen imprisoned in fine porcelain works of England a century or two ago. It is a deep heart cry, too profound and prolonged to be called poignant, yet shaken with memory of passion.

WAILLIE, WAILLIE!

When cockle shells turn silver bells,

Then will my love return to me.

When roses blow, in wintry snow,

Then will my love return to me.

Oh, waillie! waillie!

But love is bonnie

A little while when it is new!

But it grows old and waxeth cold,

And fades away like evening dew.

DIS MORNIN', DIS EVENIN', SO SOON

This arrangement is from the ballad as sung by Nancy Barnhart, painter and etcher, of St. Louis. It is a monotone of life in songtones of dusk colors and rhythms that emerge from shadows. The final verse is a scenario for a pantomime.

DIS MORNIN', DIS EVENIN', SO SOON

1. Tell old Bill, when he leaves home dis mornin',

Tell old Bill, when he leaves home dis evenin',

Tell old Bill, when he leaves home,

To let dem down-town coons alone

Dis mornin', dis evenin', so soon.

2. Bill left by de alley gate dis mornin',

Bill left by de alley gate dis evenin',

Bill left by de alley gate,

Old Sal says: Now don' be late,

Dis mornin', dis evenin', so soon.

3 Bill's wife was a bakin' bread dis mornin',

Bill's wife was a bakin' bread dis evenin',

Bill's wife was a bakin' bread,

When she got word dat Bill was dead

Dis mornin', dis eveiiin', so soon.

4. O dear, dat can't be so, dis mornin',

O dear, dat can't be so, dis evenin',

O dear, dat can't be so;

For Bill left home 'bout a hour ago,

Dis mornin', dis evenin', so soon.

5. O dear, dat cannot be, dis mornin',

O dear, dat cannot be, dis evenin',

O dear, dat cannot be,

Dey shoot my husband in de firs' degree,

Dis mornin', dis evenin', so soon.

6. Dey brought Bill home in a hurry-up wagon dis mornin',

Dey brought Bill home in a hurry-up wagon dis eveiiin,'

Dey brought Bill home in a hurry-up wagon,

Dey brought Bill home wid his toes a-draggin',

Dis mornin'. dis evenin', so soon.

OH, BURY ME NOT ON THE LONE PRAIRIE

This arrangement is from a song tnown to boys of the Crossroads Club at the University of Oregon. After a recital and reception there one evening three years ago, we held a song and story session lasting till five o'clock in the morning. Nearly all nations and the seven seas were represented. A contingent from the Black Hills of South Dakota sang this version of The Cowboy's Lament. They put their arms on each other's shoulders, stood in a circle, and cried the lines almost as a ritual from lonesome flat lands, the arms on each other's shoulders signifying that no matter how tough life might be they could meet it if they stood together. They pronounced "wind" with a long "i" as in "find" or "blind," and said the cowhands always sang it in that classical manner.

OH, BURY ME NOT ON THE LONE PRAIRIE

1 Oh, bury me not on the lone prairie,

Where the wild kiyotes will howl o'er me;

Where the rattlesnakes hiss and the wind blows free,

Oh, bury me not on the lone prairie!

They heeded not his dying prayer,

They buried him there on the lone prairie,

In a little box just six by three,

His bones now rot on the lone prairie.

CARELESS LOVE

This poem, trying to ease heartbreak, uses the simplest of words. They go to a soft, brave melody. R. W. Gordon, from whose handsome collection this comes, says it reckons among authentic folk fabrics; he has heard it with slight variations in several southern regions. Its lyric cry is brief, poignant as Sappho. Its measures are close to silence and to art "to be overheard rather than heard."

CARELESS LOVE

1. Love, oh love, oh careless love,

Love, oh love, oh careless love,

It's love, oh love, oh careless love,

You see what love has done for me.

2. Sorrow, sorrow, to rny heart,

Sorrow, sorrow, to my heart,

Sorrow, sorrow, to my heart,

When me and my true love have to part.

3. It's a pity that we ever met,

It's a pity that we ever met,

It's a pity that we ever met,

For those good times we'll never forget.

4. Now my money's spent and gone,

Now my money's spent and gone,

Now my money's spent and gone,

You passed my door a-singing a song.

5. Oh I love my mama and my papa too,

Oh I love my rnama and my papa too,

Oh I love my mama and my papa too,

But I'd leave them both and go with you.

6. Oh I cried last night and the night before,

Oh I cried last night and the night before,

Oh I cried last night and the night before,

Going to cry to-night and I'll cry no more.

7. Oh ain't it enough to break my heart,

Oh ain't it enough to break my heart,

Oh ain't it enough to break my heart,

To sec my man with another sweetheart.

8. Oh it's done and broke this heart of mine,

Oh it's done and broke this heart of mine,

Oh it's done and broke this heart of mine,

And it'll break that heart of yours some time.

THE JOHN B. SAILS

John T. McCuteheon, cartoonist and kindly philosopher, and his wife Evelyn Shaw McCuteheon, mother and poet, learned to sing this on their Treasure Island in the West Indies. They tell of it, "Time and usage have given this song almost the dignity of a national anthem around Nassau. The weathered ribs of the historic craft lie imbedded in the sand at Governor's Harbor, whence an expedition, especially sent up for the purpose in 1920, extracted a knee of horseflesh and a ring-bolt. These relics are now preserved and built into the Watch Tower, designed by Mr. Howard Shaw and built on our southern coast a couple of points east by north of the star Canopus."

THE JOHN B. SAILS

1. Oh, we come on the sloop John B. 9

My gran'fadder an' me.

Round Nassau Town we did roam,

Drinking all night, we got in a fight,

I feel so break-up I want to go home!

REFRAIN: So hoist up the John B. sails,

See how de main-s'l set,

Send for de Capt'n ashore, Lemme go home!

Lemme go home! Lemme go home!

I feel so break-up I want to go home!

2. De first mate he got drunk,

Break up de people's trunk.

Constable come aboard an' take him away,

Mr. Johnstone, please let me alone,

I feel so break-up I want to go home! (Refrain)

3. De poor cook he got fits,

Tro' 'way all de grits,

Den he took an' eat up all o' my corn!

Lemme go home, I want to go home!

Di is de worst trip since I been born! (Refrain)

JOHN HENRY

In southern work camp gangs, John Henry is the strong man, or the ridiculous man, or anyhow the man worth talking about, having a myth character somewhat like that of Paul Bunyan in work gangs of the Big Woods of the North. He is related to John Hardy, as balladry goes, but wears brighter bandannas. The harmonization is by Thorvald Otterstrom: it is massive in its pounding and evokes the atmosphere in which the powerful titan, John Henry, "does his stuff."

JOHN HENRY

1. John Henry tol' his cap'n

Dat a man wuz a natural man,

An* befo' he'd let dat steam drill run him down,

He'd fall dead wid a hammer in his han',

He'd fall dead wid a hammer in his han'.

2. Cap'n he sez to John Henry:

"Gonna bring me a steam drill 'round;

Take that steel drill out on the job,

Gonna whop that steel on down,

Gonna whop that steel on down."

3. John Henry sez to his cap'n:

" Send me a twelve-poun' hammer aroun',

A twelve-poun' hammer wid a fo'-foot handle,

An' I beat yo' steam drill down,

An' I beat yo' steam drill down."

4. John Henry sez to his shaker:

"Niggah, why don' yo' sing?

I'm throwin' twelve poun' from my hips on down,

Jes' lissen to de coP steel ring,

Jes' lissen to de col' steel ring!"

5. John Henry went down de railroad

Wid a twelve-poun' hammer by his side,

He walked down de track but he didn' come back,

'Cause he laid down his hammer an' he died,

'Cause he laid down his hammer an' he died.

6. John Henry hammered in de mountains,

De mountains wuz so high.

De las' words I heard de pore boy say:

"Gimme a cool drink o' watah fo' I die,

Gimme a cool drink o* watah fo' I die!"

7. John Henry had a little baby,

Hel' him in de palm of his han'.

De las' words I heard de pore boy say:

"Son, yo're gonna be a steel-drivin' man,

Son, yo're gonna be a steel-drivin' man! "

8. John Henry had a 'ooman,

De dress she wo' wuz blue.

De las' words I heard de pore gal say:

"John Henry, I ben true to yo',

John Henry, I ben true to yo'."

9. John Henry had a li'l 'ooman,

De dress she wo' wuz brown.

De las' words I heard de pore gal say:

"I'm goin' w'eah mah man went down,

I'm goin' w'eah mah man went down!"

10. John Henry had anothah 'ooman,

De dress she wo' wuz red.

De las' words I heard de pore gal say:

" I'm goin' w'eah mah man drapt daid,

I'm goin' w'eah mah man drapt daid!"

11. John Henry had a li'l 'ooman,

Her name wuz Polly Ann.

On de day John Henry he drap daid

Polly Ann hammered steel like a man,

Polly Ann hammered steel like a man.

12 W'eah did yo' git dat dress!

W'eah did you git dose shoes so fine?

Got dat dress f'm off a railroad man,

An' shoes f'm a driver in a mine,

An' shoes f'm a driver in a mine.

MIDNIGHT SPECIAL

This arrangement is from the song as rendered by midnight prowlers in Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas. It is impressionistic in style, delivering the substance of two lives in brief array. We see the man behind the bars looking out toward Roberta, who carries a document given her by some politician or precinct worker. The warden tells her, probably, the day is not Visitor's Day. As her man considers that he has twenty years yet to serve, he cries out that he would rather be under the wheels of a fast midnight train.

MIDNIGHT SPECIAL

Yonder come Roberta! Tell me how do you know?

By de color ob her apron and de dress she wo'.

Umberella on her shoulder, piece o' paper in her han',

She says to de cap'n: " I want my man!"

Let de Midnight Special shine a light on me,

Oh twenty long years in de pen-i-ten-tiar-y!

ALICE B.

This is arranged from the ballad as sung by Arthur Sutherland and the buccaneers of the Eclectic Club of Wesleyan University. Sutherland, who is the son of a lawyer in Rochester, New York, first heard of Alice B. when he was with the American Relief Expedition in Armenia, riding on top of a box car to Constantinople with a friend who came from New Orleans, Louisiana, and who in that gulf port one day paid $1.50 to a hobo to sing Alice B. as he, the hobo, had just heard it a few days previously in Memphis from a negro just arriving from Galveston, Texas. This is as far back as we have to date traced the Alice B. ballad. Though the verses have wicked and violent events for a theme, they point a moral and adorn a tale in their conclusion. In a sense it is propaganda in favor of the Volstead Act.

ALICE B.

1. I'm goin' out West, down on the Rio Grande,

Singin' fare-thee, O my honey, O my honey, fare-thee-well!

I'm goin' out West, down on the Rio Grande,

And it's fare-thee, O my honey, fare-thee-well!

2. The twenty-fifth of September, Martin F. a man tall and slender,

He was the man who committed that most terrible deed.

On a Sunday morning, with hardly any warning,

He shot and killed his high-brown Alice B.

3. Martin F. was a coward, he run, how he did run!

In his hand he carried a smokin' forty-one;

He ran up to de co't, says: " Judge, I committed that terrible crime,

And now I'm ready for to serve my ninety-and-nine."

4. Alice B. like a baby lay on her dyin' bed,

She says: " Mammy, I want you to take care of my little girl.

Keep her feet from slippin' through, 'cause I love her, 'deed I do,

An' I hopes to meet her in that other worlY'

5. De judge held co't de very next day;

Martin F. refused, absolutely refused, to testify.

He says: " Judge, I killed my baby, my Alice B.,

And now that I killed her I'm all ready to die."

6. "She was a good woman, an' I loved her, 'deed I did.

We had such good times, together all the time;

Till one night I went out, got filled with nigger gin,

An' when I saw her I completely los' my min'."

7. Then come all you rounders, an' all you high-browns too,

Take heed to what dis man has done.

You may go out some night, get filled with squirrel rum,

An' do the very same thing that Martin has done.

8. Then I'm goin' out West, down on the Rio Grande,

Singin' fare-thee, my honey, my honey, fare-thee-well!

I'm goin' out West, down on the Rio Grande,

Singin' fare-thee, O my honey, fare-thee-well!

PO' BOY

Po' Boy is a jail song in Oklahoma and Texas. It is also heard among post-graduates from jail in the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. We are left to infer that if the "po' boy" had made a safe getaway after taking a bag of mail from the baggage car, the woman in the case would not have run away with another man but would have stayed with him to enjoy the loot. The lilt of the song is almost gay throughout except for the steady beat of the mournful, melodious vocables of "po' boy." The "Katy" train is a reference to the Missouri, Kansas & Texas, or "K.T." railway. Of course, though this is a jail song, it is sung by many who are free and "outside."

PO' BOY

1. My mammy's in the cold, cold ground;

My daddy went away;

My sister married a gamblin' man;

And now I've gone astray.

I sit here in the prison;

I do the best I can;

But I get to thinkin' of the woman I love;

She ran away with another man.

Chorus: She ran away with another man, po' boy,

She ran away with another man.

I get to thinkin' of the woman I love;

She ran away with another man.

2.Away out on the prairie,

I stopped that Katy train;

I took the mail from the baggage car;

And walked away in the rain.

They got the bloodhounds on me,

And chased me up a tree;

And then they said, " Come down, my boy,

And go to the penitentiaree."

Chorus: She ran away with another man, po' boy, etc.

3. Oh, mister judge, oh, mister judge,

What are you going to do to me?"

"If the jury finds you guilty, my boy,

I'm going to send you to the penitentiaree."

They took me to the railroad station;

A train came rolling by;

I looked in the window, saw the woman I love;

Hung down my head and cried.

Chorus: Hung down my head in shame, po' boy,

Hung down my head and cried;

I looked in the window, saw the woman I love,

Hung down my head and cried, po' boy!