History, Symbol, and Meaning in 'The Cruel Mother'

History, Symbol, and Meaning in 'The Cruel Mother'

by David Atkinson

Folk Music Journal, Vol. 6, No. 3 (1992), pp. 359-380.

[Briefly proofed. Atkinson does not discuss the symbolism of the tying of the murdered babes hands and feet.

R. Matteson 2014]

History, Symbol, and Meaning in 'The Cruel Mother'

DAVID ATKINSON

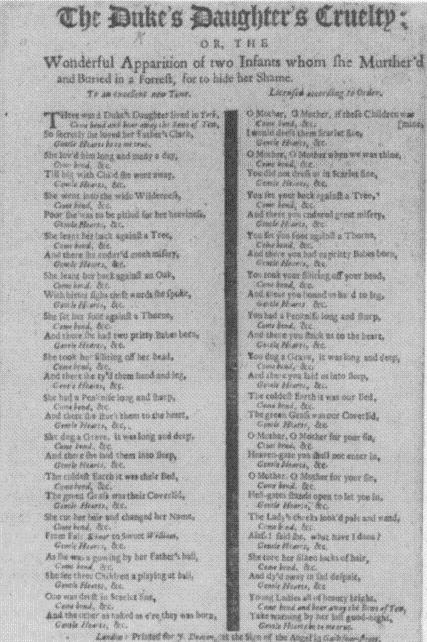

'THE CRUEL MOTHER' IS ONE of the traditional ballads which exists in an early broadside text, in this case dating from the late seventeenth century (Child 20 Version P).[1] Broadsides and traditional ballads are, of course, frequently distinguished by singers and scholars alike.[2] Nevertheless, the existence of a form of this particular ballad at a distinct historical period greatly extends the cultural history of the mother's cruelty back in time and elaborates upon its range of possible meanings.

'The Cruel Mother' tends to be considered either as a piece of supernatural lore, or else as a story of domestic crime.[3] It can, however, be more formally assigned to a sub-genre of revenant ballads, defined on the basis of their constituent tale roles.[4] Tale role analysis describes the characters of traditional narrative according to their functions, and this allows the establishment of categories of structurally and also culturally related ballads. Others included in the same sub-generic grouping are 'The Wife of Usher's Well' (Child 79), 'Proud Lady Margaret' (Child 47), 'Sweet William's Ghost' (Child 77), and 'The Unquiet Grave' (Child 78). The characters of 'The Cruel Mother' and of these other revenant ballads occupy self-explanatory tale roles of Visited (the mother) and Revenant (her children).

The revenant ballads characteristically deal with the dislocation of death and the reaction to it of living women. Accordingly, in 'The Cruel Mother', the revenants reject the mother's refusal to acknowledge their identity as her own dead children, and compel her to recognize her responsibility for their deaths.

The cultural emphasis established in this way fully reflects the fact that in the tradition of 'The Cruel Mother' the dialogue between the mother and her revenant children constitutes the persistent core of the ballad.[5] She encounters them (frequently playing at ball) and says that if they were her children she would treat them well, to which they reply that they were once hers but that she killed them. In consequence, they usually tell her that she is destined to go to hell, or sometimes to undergo instead a series of expiatory penances. Numerous versions of 'The Cruel Mother', however, also include an initial account of a romantic relationship, which may be socially unequal, and of the birth of illegitimate children, as well as a description of the details of the murder. This material is present in the early broadside text, entitled 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty'

Figure I:

The broadside bears the imprint of Jonah Deacon at the sign of the Angel in Giltspur Street in London, where he was active as a bookseller from around 1684, and it was evidently licensed before the final lapse of the Licensing Act in 1695.[6] This dating then provides a historical context for the subjects of illegitimacy and infanticide.

In fact, the publication of the broadside came during a period when the overall level of illegitimacy in England was very low.[7] Economic and biological factors, legal measures, and perhaps most importantly various informal sanctions at a local level are all likely to have been significant in suppressing illegitimacy. Statutes of I576 and 1610 were intended to prevent illegitimate children from becoming a charge on the parish rates, and informal controls undoubtedly had the same intent. Most of those who did bear illegitimate children tended to come from the poorer end of the socio-economic scale, often maidservants who may have suffered sexual exploitation.

The regulation of sexual morality, therefore, served to reinforce social norms in relation to marriage, inheritance, and economic relations within the community. Individuals attempted to avoid the risk of illegitimacy by practicing contraception, abortion, and ultimately infanticide, although it is difficult to determine the incidence of such practices. However, infanticide was distinguished as a separate offense from murder in 1624, and a small but steady stream of prosecutions persisted into the late seventeenth century.[8] The statute was particularly intended to prevent the killing of illegitimate children, and it also made an offense of the concealment of stillbirths by unmarried mothers. Once more, those convicted were usually women from the poorer end of the socio-economic scale, again often maidservants, motivated by shame and panic. The implication is that the infanticide legislation w as a further extension of the control of sexual morality and hence of social and economic relations, rather than an attempt to protect the lives of infants.

The content of 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty' is given a degree of official sanction by its approval under the Licensing Act. The commercial constraints of the broadside market would most probably also favour social conservatism in the text.[9] The orthodox religious conclusion, stated in stanzas 22 ('O Mother, 0 Mother for your sin, / Heaven-gate you shall not enter in') and 23 ('O Mother, O Mother for your sin, / Hell-gates stands open to let you in'), readily contributes to a culture of tight controls over illegitimacy and infanticide. The social purpose o f the broadside i s emphasized by the conventional moral, addressed to women of child-bearing age, which is drawn in stanza 26 ('Young Ladies all of beauty bright,/ Take warning by her last good-night'). The 'goodnights' of condemned criminals constituted a distinct class of broadsides, paralleled in other forms of popular literature, which were intended to provide warning examples to their audiences.[10] 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty' depends upon a largely atypical occurrence, but this in itself is common in traditional songs and other kinds of popular literature as well, which thereby reinforce the definition of social norms." The atypicality of the story is especially emphasized by the social status of the mother, who no doubt provided a conspicuous example to persons lower down the socio-economic scale, at whom the broadside market was primarily aimed.

The anonymous duke's daughter, however, is more typical of the characters of the oldest versions o f traditional ballads than of those of late seventeenth-century broadsides [11]. The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty' also departs from the first-person narration and the perspective of contrition which are conventional in broadside 'goodnights'. These are well represented by an earlier seventeenth-century broadside, by Martin Parker, entitled 'No naturall Mother, but a Monster', in which a maidservant expresses in characteristist cycle her remorse for having killed her illegitimate child.[12]

In contrast, 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty' is stylistically something of an amalgam. It is written in four-stress couplets with a refrain, a form which may be characteristic of the earliest British ballads, but is not so typical of late seventeenth-century broadsides.[13] The story is told dramatically and with economy of expression, but also develops ritualistically, with marked parallelisms of phrase and idea, giving rise to an effect of incremental repetition. These are all common aspects of traditional ballad style.

On the other hand, the clear emergence in the final stanza of the voice of the presenter to draw a moral out of the story is more typical of seventeenth-century broadside writing.[14] Equally incongruous for a traditional ballad is the mother's reported exclamation, 'Alass! said she, what have I done?' It is conceivable that 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty' represents the broadside origin of 'The Cruel Mother', perhaps deliberately incorporating imitations of the style of traditional ballads. However, it has not obviously served to fix the text of subsequent versions, some of which can be cited to demonstrate that 'The Cruel Mother' has genuinely been in oral circulation.'" (There may be some evidence of the influence of the printed text in recurrences of the setting in York and the character of the father's clerk.) Moreover, there are various pieces of indirect evidence that an oral tradition lies behind the broadside, reinforcing the stylistic impression that it represents a form of a ballad already in existence, to some extent adapted to broadside conventions.

There is a general agreement that in 'The Maid and the Palmer' (Child 21) the revelation that the woman has murdered her children derives from 'The Cruel Mother'.[16] This revelation occurs in Child 21A which is present in the Percy folio manuscript of the mid-seventeenth century, and therefore points to the existence of 'The Cruel Mother' prior to 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty'. (The same material is present in a Danish broadside text of 'The Maid and the Palmer' which dates from about 1700, while 'The Cruel Mother' was first recovered in Denmark in the nineteenth century.) The basis for this transfer of material appears to have been a perceived similarity in narrative and emotional situation, since each of the ballads involves a woman's desire to conceal the evidence of her unchastity. Subsequently, the process was evidently repeated in the reverse direction, since the purgatorial penances imposed in 'The Maid and the Palmer' are also present in some versions of 'The Cruel Mother' recovered since the early nineteenth century.

Stanza 11 of 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty', in which 'She cut her hair and changed her Name, / From Fair Elinor to Sweet William', has no relevance to the story of 'The Cruel Mother'. It apparently derives from 'The Famous Flower of Serving-Men' (Child 106).[17] A text of this ballad communicated to Percy in 1776 includes the couplet, 'I cut my locks, and chang'd my name / From Fair Eleanore to Sweet William'.[18] The same incident is described in a slightly different manner in a broadside text of 'The Famous Flower of Serving-Men' which was entered in the Stationers' Register on 14 July 1656, and was therefore in existence before 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty'.[19] This text carries the initials L. P., for Laurence Price, who was also responsible for broadsides of 'Robin Hood's Golden Prize' (Child 147) and 'James Harris (The Demon Lover)' (Child 243), although any of these might be adaptations of traditional material.

Thieves murder the heroine's husband in the broadside, and her child as well in Percy's text. Her disguising of herself as a man represents her means of coping with despair and starting a new life. There is therefore a perceptible similarity in narrative and especially emotional situation with the point at which stanza 11 occurs in 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty', which could again provide the basis for the transfer of material. Such a process seems much more likely to have taken place in oral tradition than in the course of broadside composition.

Structural analysis of 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty' also provides indirect evidence that an oral tradition lies behind the broadside (see Figure 2). Characteristic of oral ballads are binary, trinary, and framing or annular patterns at different levels of structural organization. [20] In 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty', stanzas consistently fall into groups of two or three to each unit in the story. The repetition of the consecutive accounts of the birth, murder, and burial of the children then divides the ballad into two parts which are structurally linked. This division is further reinforced and the two parts balanced by the narrative form of the first part and the predominantly direct speech of the second part. The effect is of a simple but strong tonal structure to the ballad. The character structure more straightforwardly incorporates both the mother and her children throughout the main body of the story, which is bracketed by an introduction and a coda which involve the mother alone. Most importantly, though, the overall architectonic is consolidated by a complicated stanzaic structure, which depends upon verbal parallels between stanzas.

Figure 2: Structural patterns in 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty'

This very complexity provides two different models for the stanzaic structure, which need not be considered as mutually exclusive. The most comprehensive of these builds upon pairs and triads among adjacent stanzas. The opening formula of the first line in stanza 4 ('She leant her back against a Tree') is repeated in stanza 5 ('She leant her back against an Oak'). The verb is altered in stanza 6 ('She set her foot against a Thorne'). However, the opening formula of the second line in stanza 4 ('And there she endur'd much misery') is repeated in stanza 6 ('And there she had two pritty Babes born'), but not in stanza 5 ('With bitter sighs these words she spoke').

Stanzas 4, 5, and 6 therefore constitute a triad, with possibly a rather looser link in stanza 5 which seems designed to incorporate the refrain into the ballad story. The general movement of the first lines in stanzas 4, 5, and 6 is then echoed in stanzas 7 ('She took her filliting off her head'), 8 ('She had a Penknife long and sharp'), and 9 ('She dug a Grave, it was long and deep'). More specifically, the opening formula of the second lines in stanzas 7 ('And there she ty'd them hand and leg'), 8 ('And there she stuck them to the heart'), and 9 ('And there she laid them into sleep') repeats the opening formula of the second lines in stanzas 4 and 6. Stanzas 7, 8, and 9 therefore make up a second triad, which is intimately related to the first triad. This whole arrangement is then very closely reiterated in stanzas 16 and I7, and stanzas 18, 19, and 20, in the second part of the text.

The repeated patterns in the two parts thus form a frame around the central meeting of the mother with the revenant children. This elaborate scheme is then held in place by another frame based on the quite different form of stanza 10 ('The coldest Earth it was their Bed, / The green Grass was their Coverlid'), which is very closely reiterated in stanza 21. This first model emphasizes the unity of each of the two parts of the text over and above their relationship to one another.

The alternative model for the stanzaic structure begins with the very close reiterations of stanzas 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 in stanzas 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, and 21 respectively (stanzas 16 and I7 both repeating the verb 'set' of stanza 6 rather than 'leant' of stanza 4). These stanzas therefore form a whole sequence of framing devices. This second model emphasizes the intimate relationship between the two parts of the text. On both of these models, the central confrontation between the mother and the revenant children is then linked to the final prediction of her eternal fate. The opening formula of the first line and the descriptive detail of the second line in stanza 14 ('O Mother, 0 Mother, if these Children was mine, / I would dress them Scarlet fine') are both repeated in stanza 15 ('O Mother, 0 Mother when we was thine, / You did not dress us in Scarlet fine').

Stanzas 14 and 15 therefore constitute a pair. The opening formula of the first line in stanzas 14 and 15 is repeated in stanzas 22 and 23, in which the opening lines are identical ('O Mother, O Mother for your sin'). The general movement of the second line in stanza 22 ('Heaven-gate you shall not enter in') is also repeated in stanza 23 ('Hell-gates stands open to let you in'). Stanzas 22 and 23 therefore make up another pair, which with stanzas 14 and 15 form a concluding frame. This final framing device tends to reinforce the division of the text into two balanced parts.

The apparently simple broadside text thus proves to be highly elaborate, displaying structural patterns characteristic of oral literature. The structural analysis coincides with the evidence from the transfer of material between ballads that an oral tradition lies behind the broadside. The structural patterns which emerge constitute a synchronic structure for 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty', or for a traditional ballad on which the broadside is based. The recurrence of material in subsequent versions of 'The Cruel Mother' constitutes a diachronic structure for the ballad. The two structures in combination can then be employed to provide evidence about the status of particular elements of the broadside text within the ballad tradition.

Thus stanza 11 of 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty', in which the mother cuts her hair and changes her name, is not integrated into any of the levels of the synchronic structure, and does not recur in the diachronic structure. This tends to confirm conclusively that it is not integral to the story of 'The Cruel Mother'. On the other hand, although stanzas 12 ('As she was a gowing by her Father's hall, / She see three Children a playing at ball') and 13 ('One was drest in Scarlet fine, / And the other as naked as e're they was born') are not altogether verbally integrated into the stanzaic level of the synchronic structure, the diachronic structure indicates that the meeting with the revenant children is absolutely intrinsic to the ballad. Indeed, playing at ball very frequently recurs, and the father's hall is quite common, in this part of the ballad.

The appearance of three children playing at ball in stanza 12 seemingly contradicts stanza 6 in which only two are born. Stanza 13 distinguishes the one child dressed 'in Scarlet fine' from 'the other as naked as e're they was born', which may be either singular or plural. The stanzaic level of the synchronic structure strongly supports the integrity of the opening formula of the firstl ine in stanza 14 ('O Mother, 0 Mother, if these Children was mine, / I would dress them Scarlet fine'). The broadside text provides no punctuation to identify the different speakers, but clearly the mother herself cannot begin in this manner. Equally, the revenant children cannot speak in stanza 14, but do so in stanza 15 ('O Mother, 0 Mother when we was thine, / You did not dress us in Scarlet fine'). Stanzas 22 and 23, which form a frame with stanzas 14 and 15, are in an appositional rather than a directly contradictory relationship to one another, and stanzas 14 and I5 may consequently share the same relationship. The logical demands of this part of the text can be met if stanza 14 ('O Mother, 0 Mother, if these Children was mine, / I would dress them Scarlet fine') is spoken by the additional child of stanza 12. This figure must be the one child dressed in scarlet, 'the other' of stanza 13 being the two naked children who were born in stanza 6 and who speak in stanza 15 ('O Mother, 0 Mother when we was thine, / You did not dress us in Scarlet fine').

There is support from the diachronic structure for the occasional presence in the tradition of 'The Cruel Mother' of additional figures playing at ball with the revenant children. In Child 20F, one child is born and murdered, but the mother afterwards encounters two at play. The discrepancy over the number of children is associated with a distinction based on their clothing, or lack of it, in various different versions from both the Old and the New Worlds. In Child 20[O], two children are killed, but the mother then sees three playing at ball, 'The one was clothed in purple, the other in pall, /And the other was cloathed in no cloths at all' ('pall' being a rich purple cloth). Elsewhere, one child is murdered, but two appear playing ball, one dressed in silk and the other 'naked to the wind'.[21] In another version, two are killed, but the mother sees three playing with a ball, one dressed in silks and the other two naked.[22] In yet another, one is murdered, but three are playing at ball, 'One dressed in silk the other in satin, / The other star[k] naked as ever was born'.[23]

That the distinction between rich attire and nakedness can impart an element of symbolism to 'The Cruel Mother' is evident from the description of the three murdered children playing at ball in Child 20H:

The first o them was clad in red,

To shew the innocence of their blood.

The neist o them was clad in green,

To shew that death they had been in.

The next was naked to the skin,

To shew they were murderd when they were born.

A slightly different kind of symbolism is apparent in some New World versions of 'The Cruel Mother' in which the revenant form of the one murdered child is seen playing ball with two additional children named Peter and Paul.[24] In one of these, Peter and Paul are distinguished from the third child which is 'as naked as the hour it was born'.[25] In 'Lady Anne', a song related to 'The Cruel Mother', Peter and Paul again appear playing at ball with the murdered child, and it is Peter who first addresses the mother.[26] The names Peter and Paul in a ballad which involves Christian eschatology almost inevitably suggest a symbolic association with the saints of those names, since Saint Peter conventionally determines who may enter the gates of heaven. Thus the occasional presence in the tradition of 'The Cruel Mother' of additional figures playing at ball with the revenant children may be symbolically connected with the eternal fate of the mother. A figure with this significance would accord with the logic of the text of 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty', which demands that the mother is first addressed by the additional child dressed in scarlet.

David C. Fowler, in a footnote in A Literary History of the Popular Ballad, suggests that the child dressed in scarlet in 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty' may be identified with the infant Christ.[27] A parallel is indicated with the scriptural story in which King Nebuchadnezzar had three young men, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, cast into a fiery furnace. The king then saw four figures walking in the midst of the fire, the fourth appearing to him 'like the Son of God' (Daniel, iii. 25). This story was interpreted as a prophecy of the incarnation in medieval theology. Playing ball is associated with the Christ child as early as the fifteenth century in The Childhood of Jesus, and also The Life of Saint Anne, vernacular stanzaic narratives which include a number of motifs and episodes which are also present in various ballads and carols.[28] Among these ballads is 'The Bitter Withy', in which the infant Christ expresses the wish to play at ball with some other children, and which seems likely to date from beforet he Reformation even though it was not recovered until much later.[29] Scarlet dress can symbolize the blood of Christ, much as red clothing shows 'the innocence of their blood' for the murdered children of Child 20H. In 'The Corpus Christi Carol (OverY onder'sa Park)', first known in a manuscript of the early sixteenth century, the colour red symbolizes Christ's blood.[30]

This symbolism persists in pseudo-biblical folklore.[31] Equally, scarlet or purple, which also occurs in 'The Corpus Christi Carol', is appropriatete the majesty of Christ (and this may perhaps extend to any bright and rich material such as silk or satin).[32] Symbolic imagery of this kind may, then, attach to any of the additional figures playing at ball with the revenant children in the tradition of 'The Cruel Mother'. In Child 20[O], two children are murdered, and then two clothed in purple and pall appear playing at ball with a third w ho is naked. The symbolic imagery is apparently reversed, and the final stanza gives the explanation, 'We are three angels, as other angels be'.

There is some indication from the diachronic structure that there is scope for the occasional presence in the tradition of 'The Cruel Mother' of a symbolic figure of Christ. In several versions, the children are 'in the heavens high', or some such formulation, and therefore implicitly in the presence of the Christian deity, at the same time as they appear to the mother in the corporeal form characteristic of ballad revenants.[33] Much the same inference can be drawn from the conclusion of Child 20[O]. In a version of 'Lady Anne', the mother finds the figure of her child obscuring that of God as she tries to pray, 'Oay, my God, as I look to thee, / My babe's atween my God and me'.[34] The Danish ballad of 'The Cruel Mother' is even more explicit about the presence of the Christian deity, since the children seek permission before they return to confront their mother, 'They went and before Our Lord they stood: / "Might we go home to our mother, we would" '.[35]

It has, in fact, long been recognized that ballads do contain symbolic effects, and that these appear to have referred to widely understood cultural ideas embodied in a common fund of imagery.[36] Nevertheless, the potential symbolism which can be identified in the ballads may not always seem very readily recognizable. However, the emphasis in more recent scholarship on the importance of context for the understanding of traditional events has also demonstrated the interpretative possibilities created by connotation within the group or community.[37] This strongly reinforces the possibility of symbolic effects being both present and understood in such events.

In the case of past performances of ballads, a source of connotation which can be assumed lies in the experience of traditional song shared by their singers and audiences. Thus a child playing at ball and dressed in scarlet would be more likely to suggest a symbolic association with the infant Christ among a group familiar with the kind of material which appears in 'The Bitter Withy' and 'The Corpus Christi Carol'.

Given this source of connotation, the symbolism of 'The Cruel Mother' can be tested against another instance of a child playing at ball, in 'Sir Hugh, or, The Jew's Daughter' (Child I55). Although this ballad is only known from the mid-eighteenth century, it may well have originated considerably earlier. Legends of Hugh of Lincoln, the Christian boy who was supposedly ritually executed by the Jews, date back at least to the thirteenth century. Versions of the ballad exist which show the influence of 'The Bitter Withy', indicating association in the course of tradition.[38] There are also a few versions in which the 'Jew's daughter' has become the phonetically similar 'duke's daughter', which in turn might conceivably recall the central character of 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty'.[39] The story of Sir Hugh is rather one of anti-Semitic prejudice than of religious beliefs, but the apple from the garden with which he is enticed in the ballad is almost certainly a symbol of the Temptation and Fall in the Garden of Eden.[40] If in addition the activity of playing at ball again carries a symbolic association with the infant Christ, the story is assimilated not only to the Fall but also to its recapitulation and redemption in the life of Christ from infancy through to ritual execution. The ballad thus includes a range of symbolic reference to Christian tradition, which probably provides a basis for the persistence of the story of Sir Hugh as a piece of anti-Semitic propaganda. Precisely because this basis is somewhat predictable, it tends to confirm the interpretation of the child playing at ball in the ballad context as a symbolic figure of Christ.

An analogy for the occasional presence and the thematic consequences of a symbolic figure of Christ in the tradition of 'The Cruel Mother' can be drawn from 'The Wife of Usher's Well'. In fact, there exists a version of 'The Cruel Mother' which shows traces of 'The Wife of Usher's Well' in both text and tune, indicating association in the course of tradition.[4]" In 'The Wife of Usher's Well', a woman refuses to accept the deaths of her children, and she prays that they may return to her. The revenant children visit her for one night before returning to the otherworld at dawn, compelling her to acknowledge that they are dead, and occasionally to recognize that her own pride was instrumental in their deaths. The revenant children in very many New World versions refer to the figure of the Saviour awaiting their return to heaven. In an Old World version, the crowing of the cock has apparently prompted the transfer of a stanza from 'The Carnal and the Crane' (Child 55) which includes the figure of Christ.[42] Most significantly, in Child 79C, an unusual version from Shropshire, a widow prays to Christ that her three dead sons be sent to visit her in order to give her rest. Her request is granted, and afterwards the revenant sons lead their mother to a 'chaperine' (chapel?) and into the presence of Christ. He welcomes the sons inside, but sends their mother away, giving her nine days to repent 'For the wickedness that thou hast done'. This remains unspecified but can perhaps be compared with the fatal pride which is mentioned elsewhere. After the nine days Christ receives her into heaven. The revenant children are thus associated with the figure of Christ in a drama of eternal judgement.

The drama of eternal judgement tends to belong to a sub-genre of religious ballads, the characters of which occupy tale roles of Sinner, Adversary, and Interceder.[43] The religious ballads characteristically deal with the commission or revelation of a sin and the subsequent divine reaction. The characters of Child 79C could, then, be considered to function in the religious ballad tale roles of Sinner (the widow), Adversary (her sons), and Interceder (Christ). Nevertheless, the widow and her sons would plainly continue to occupy the revenant ballad tale roles of Revenant and Visited as well. In fact, this version incorporates the characteristic concerns of both of the different sub-genres. The dislocation of death and the mother's reaction to it are linked by the appearance of the revenant sons to the revelation of her wickedness and the subsequent divine reaction. The effect of the introduction of the figure of Christ into 'The Wife of Usher's Well' is therefore one of extension of the range of cultural reference of the ballad version.

The analogy of 'The Wife of Usher's Well' suggests that a comparable effect may derive from the occasional presence of a symbolic figure of Christ in the tradition of 'The Cruel Mother'. It is even conceivable that the characters could be considered to function in the religious ballad tale roles of Sinner (the mother), Adversary (her children), and Interceder (Christ). Nevertheless, the revenant ballad tale roles of Revenant and Visited occupied by the children and the mother certainly remain dominant. The characteristic concerns of both of the sub-genres are therefore present, but in unequal degrees. The mother is compelled by the appearance of her revenant children to recognize her responsibility for their deaths, and the subsequent divine reaction which they predict is foreshadowed by the presence of the symbolic figure of Christ. In consequence, the ballad has some of the immediacy of a drama of eternal judgement. A similar effect may be produced in versions of 'The Cruel Mother' in which additional figures bearing the names of Peter and Paul symbolize the presence of the saints.

An equivalent effect may, moreover, derive from the symbolic imagery of 'The Cruel Mother' even in versions which do not include additional figures. The revenant children very frequently play at ball. Red clothing serves to distinguish one of them, even when they have all been murdered, in Child 20H. Another version, which only begins with the appearance of three children playing ball, has one dressed in 'scarlet fine' and two others 'just like they was born'.[44] In a version in which three murdered children appear playing ball, two are named Peter and Paul and are distinguished from the third which is 'as naked as the hour it was born'.[45] Sometimes the mother offers to dress the revenant children in scarlet." While all of these characters are still the cruel mother's revenant children, the symbolic imagery can nonetheless endow the ballad with some of the immediacy of a drama of eternal judgement. Consequently, the occasional presence of a symbolic figure of Christ in the tradition of 'The Cruel Mother' may represent merely an emphatic instance of a symbolic effect which more commonly functions without the introduction of additional figures.

Some analogies for this more common kind of symbolic effect can be drawn from the identification of religious elements in secular ballad versions. 'The Corpus Christi Carol' has an early seventeenth century secular counterpart in 'The Three Ravens' (Child 26). Some of the elaborate religious symbolism of the carol can still be traced in the ballad, even though the description of the dead knight can function without it, as in the Scottish adaptation, 'The Twa Corbies'. The faithful female attendant (the fallow doe) and the bloody head and red wounds lend the central image of the ballad the attributes of a pieta. Again, the earliest known version of 'Riddles Wisely Expounded' (Child 1), in a manuscript of the mid-fifteenth century, comprises a contest between the Devil and a maid, in which she defeats him by successfully answering his questions, and at the end she identifies him by name.[48] In the later seventeenth-century broadside version (Child 1A), the contest takes place between a knight and a woman, and her success w ins his hand in marriage. Although her naming of the Devil here passes without consequence, it can still serve as a touchstone for the nature of the knight, and hence as a reminder that the wisdom involved in courtship is related t o moral knowledge of a more universal kind.[49] Concomitantly, in some uncharacteristic versions of 'Captain Wedderburn's Courtship' (Child 46) in which the captain is unsuccessful, there are indications that he can be identified with the Devil.[50]

One of these versions, which can still be understood as a story of courtship, is given the title of 'The Devil and the Blessed Virgin Mary', confirming the identification of the religious drama on the part of the singer.[51] A degree of secularization appears to have taken place during the course of transmission of the legend behind 'The Maid and the Palmer'. This ballad has its basis in the gospel story of the woman of Samaria, of whom Christ requested a drink from a well, afterwards revealing to her His knowledge of her unchastity (John, iv. 6-26)." The story of the Samaritan woman is conflated with the legend of Mary Magdalen, in which her early life was given over to unchastity, and from which the purgatorial penances derive. Mary Magdalen is also identified with the woman 'which was a sinner' (Luke, vii.37), and with Mary of Bethany, whose sister Martha underwent a ustere p enances i n medieval legend. Scandinavian versions of 'The Maid and the Palmer' name the figures of Mary Magdalen and of Christ, who may appear as an old man. The characters of the ballad in English are a maid and a palmer, old man, or gentleman. In Child 21A, once the palmer reveals to the woman his knowledge that she has murdered her children, she addresses him, 'But I hope you are the good old man / That all the world beleeues vpon', and submits herself to the imposition of penances. Furthermore, the singer of an Irish version, in which the male character is called a 'gentleman', is said to have made the identification with Christ in a personal comment.[53] This figure can therefore be quite readily equated with the person and the authority of Christ, and so the characters can occupy the religious ballad tale roles of Sinner (the maid), Adversary (the palmer), and Interceder (Christ).[54] A drama of eternal judgement is thus predicated upon the associations attaching to a character, in much the manner posited for 'The Cruel Mother'. The effect serves to reinforce the similarity of narrative and emotional situation which appears to provide the basis for the transfer of material between these two ballads in the course of tradition.

The identification of religious elements in secular ballad versions clearly demands a degree of cultural knowledge on the part of singer and audience. This is equally a requirement for the recognition of the drama of eternal judgement from symbolic imagery in 'The Cruel Mother'. As a general principle, it is recognized that a shared cultural context can create a crucial part of the meaning in traditional events.-" Thus the presence of symbolic imagery in 'The Cruel Mother' provides a model for the generation of meaning in ballad performance which is dependent upon the interaction of text and context. The ballad story is interpreted according to the shared understanding of the group or community.

In practice, the apparently simple occurrence of infanticide is closely integrated into a complex of behavioural and ethical issues, including in particular that of abortion.[56] The story of 'The Cruel Mother' may therefore function as a correlative for the psychological consequences of a range of events such as abortion or abandonment, and even stillbirth or accidental neonatal death (including overlaying or sudden infant death syndrome), besides infanticide itself. Moreover, infanticide need not necessarily involve the killing of an unwanted child, and filicidal impulses may be a not uncommon aspect of motherhood.[57] Although the majority of cases of infanticide involve the mother, the father or both parents jointly are on occasion responsible. Thus the ballad might serve as a working through of disturbing emotions associated with maternity and parenthood in general. The source information accompanying published versions indicates that the majority, but by no means all, of their singers have been women.

The primary cultural effect of 'The Cruel Mother' is thus cathartic, and not prescriptive. Nevertheless, limits to maternal control over the beginning of life are set out, in a manner comparable with 'The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty,' in versions which include an initial account of a romantic relationship and the birth of illegitimate children. A continuing interest in the definition of such limits is evident from some more unusual versions in which the social parameters are varied in a number of ways. Thus one in which the mother marries and then murders her children, with no apparent motive, may project them as the unwanted consequences of a legitimate relationship.[58] Somewhat similarly, in a song related to 'The Cruel Mother', the children are perceived by their widowed mother as an impediment to a new romantic relationship, and she accordingly kills them, albeit to no avail.[59] Another version of the ballad seems to imply that poverty adds to the problem of illegitimacy.[60] In yet another, the mother is paid to kill her illegitimate children, so that she becomes merely the instrument of social convenience.[61] Elsewhere, there are some indications that limits to maternal control over the beginning of life may not in fact be absolute. A version in which the mother appears to bind and bury the revenant children, perhaps in order to prevent them from haunting her, could imply that she can successfully resist acknowledging her guilt.[62] In an apparently unique Scottish version, the mother kills her illegitimate son, but then instead of telling her that she is destined to go to hell, the revenant child seems to hold out the possibility of mercy.[63] Undoubtedly, though, a traditional ballad of 'The Cruel Mother' can serve a function of reinforcing the definition of social norms for the group or community.

A model for the generation of meaning in ballad performance derived from the presence of symbolic imagery in 'The Cruel Mother' has the effect of incorporating the ballad story with the shared understanding of the group or community. This embraces psychological awareness, but it can also prescribe limits to individual behaviour. As a conclusion this is broadly compatible with the general import of the revenant ballads which emerges from tale role analysis. They exemplify the methods by which communal wisdom is transmitted in order to maintain the psychological equilibrium both of individuals and of the group." This convergence of approach, then, provides some confirmation for the validity of a model for the generation of meaning in ballad performance which is dependent upon the interaction of text and context, even though it derives initially from a seventeenth-century broadside.

------------------

Notes

1. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. by Francis James Child, 5 vols (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, I88z-98; repr. New York: Dover, I965), II, 500-01; III, 502; and iv, 45I. Child originally assigned the version 20O, but later corrected this to 20P.

2. See David Buchan, The Ballad and the Folk (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972), p. 67; Natascha Wurzbach, 'An Approach to a Context-Oriented Genre Theory in Application to the History of the Ballad: Traditional Ballad - Street Ballad - Literary Ballad', Poetics, iz (I983), 52-62.

3. See M. J. C. Hodgart, The Ballads, znd edn (London: Hutchinson, 196z), p. 15; the classification in The Viking Book of Folk Ballads of the English-Speaking World, ed. by Albert B. Friedman (New York: Viking, 1956).

4 David Buchan, 'Tale Roles and Revenants: A Morphology of Ghosts', Western Folklore, 45 (I986), I44-5I. See also David Buchan, 'Propp's Tale Role and a Ballad Repertoire', Journal of American Folklore, 95 (I98z), 159-7z; David Buchan, 'Talerole Analysis and Child's Supernatural Ballads', in The Ballad and Oral Literature, ed. by Joseph Harris, HarvardE nglishS tudies,I 7 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), pp. 60-77.

5 See Tristram Potter Coffin, The British Traditional Ballad in North America, rev. edn with a supplement by Roger de V. Renwick, Bibliographical and Special Series, American FolkloreS ociety( Austin:U niversityo f Texas Press,I 977), p. 22I.

6 The Roxburghe Ballads, Vols I-3 with notes by Wm. Chappell, Vols 4-9 ed. by J. Woodfall Ebsworth, 9 vols (London and Hertford: Ballad Society, I869-99), I, xix.

7 Peter Laslett, Family Life and Illicit Love in Earlier Generations: Essays in Historical Sociology, repr. with corrections (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1 980), pp. 102-59; Bastardy and its Comparative History: Studies in the History of Illegitimacy and Marital Nonconformism in Britain, France, Germany, Sweden, North America, Jamaica and Japan, ed. by Peter Laslett, Karla Oosterveen, and Richard M. Smith (London: Edward Arnold, I980), Chapters 1-8. See also G. R. Quaife, Wanton Wenches and Wayward Wives: Peasants and Illicit Sex in Early Seventeenth Century England (London: Croom Helm, 1979), pp. 56-57, 202-4z; J. A. Sharpe, Crime in Seventeenth-Century England: A County Study, Past and Present Publications (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Paris: Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, I983), pp. 59-60; Martin Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England, 1570-I640, Past and Present Publications (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), pp. 152, I54, I57-67, z75-8I.

8. Peter C. Hoffer and N. E. H. Hull, Murdering Mothers: Infanticide in England and New England I558-I803, New York University School of Law Series in Legal History, 2, Linden Studies in Anglo-American Legal History (New York: New York University Press, 198I); Keith Wrightson, 'Infanticide in European History', Criminal Justice History, 3 (i98z), 1-20; Sharpe, Crime in Seventeenth-Century England, pp. I35-37; J. A. Sharpe, Crime in Early Modern England 1550-1750, Themes in British Social History (London: Longman, I984), pp. 60-62, 109-10.

9. See Natascha Wurzbach, The Rise of the English Street Ballad, 1550-1650, trans. by Gayna Walls, European Studies in English Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, I990), p- 25.

10. Friedman, pp. 218-19; Wurzbach, The Rise of the English Street Ballad, p. 144.

11. Vic Gammon, 'Song, Sex, and Society in England, I600-I850', Folk Music Journal, 4 (1982), 235-38.

12. A Pepysian Garland: Black-Letter Broadside Ballads of the Years 1595-1639, Chiefly from the Collection of Samuel Pepys, ed. by Hyder E. Rollins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, I92Z), PP. 425-30.

13. See David C. Fowler, A Literary History of the Popular Ballad (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, I968), pp. ii-iz; Buchan, The Ballad and the Folk, pp. I67-70.

14. Wurzbach, The Rise of the English Street Ballad, p. 65.

15. See J. Barre Toelken, 'An Oral Canon for the Child Ballads: Construction and Application', Journal of the Folklore Institute, 4 (1967), 88.

16. Child, I, z3o; David Buchan, 'The Maid, the Palmer, and the Cruel Mother', Malahat Review, no. 3 (July I967), IOI-05.

17. Child, II, 501.

18. Child, II, 429.

19. A Transcript of the Registers of the Worshipful Company of Stationers, from I640-1708 A.D., [ed. by G. E. Briscoe Eyre and Charles Robert Rivington], 3 vols (London: privately printed, 19I3-14), II, 73.

20. See Buchan, The Ballad and the Folk, pp. 87-144.

21. Phillips Barry, Fannie Hardy Eckstorm, and Mary Winslow Smyth, British Ballads from Maine: The Development of Popular Songs with Texts and Airs (New Haven: Yale University Press, I929), 84-85 (D).

22. Ozark Folksongs, ed. by Vance Randolph, rev. edn, 4 vols (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1980), I, 73-74 (also in Vance Randolph, The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society(New York: Vanguard Press, 1931), pp. i85-87).

23. [A. G. Gilchrist], 'Five English Folk Songs', Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, i (I934), 130-32.

24. Ancient Ballads Traditionally Sung in New England: From the Helen Hartness Flanders Ballad Collection, Middlebury College, Middlebury, Vermont, ed. by Helen Hartness Flanders, critical analyses by Tristram P. Coffin, music annotations by Bruno Nettl, 4 vols (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, I960-65), I, 233-35 (B), 235-36 (C); Cecil J. Sharp, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, ed. by Maud Karpeles, 2 vols (London: Oxford University Press, I93z), i, 6z (L).

25. Sharp, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, I, 62 (L).

26. Child, 1, 227; The Greig-Duncan Folk Song Collection, ed. by Patrick Shuldam-Shaw, Emily B. Lyle, and others (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press in association with the School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh, I98I-), II, 35.

27 Fowler, p. 44.

28 Gordon Hall Gerould, 'The Ballad of "The Bitter Withy"', PMLA, 23 (I908), 162; Janet M. Graves, "'The Holy Well": A Medieval Religious Ballad', Western Folklore, 26 (I967), 2I-z4; Fowler, pp. 44, 46-58. See Sammlung Altenglischer Legenden, ed. by C. Horstmann (Heilbronn: Gebr. Henninger, I878), P. IzO (British Library, Harleian MS 2399, 1. 599); [C. Horstmann], 'Nachtrage zu den Legenden', Archiv fur das Studium der Neueren Sprachen und Litteraturen, 74 (I885), 336 (British Library, Additional MS 31042, 1. 672); The Middle English Stanzaic Versions of the Life of Saint Anne, ed. by Roscoe E. Parker, Early English Text Society, Original Series, 174 (London: Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society, 19z8), P. 7I (University of Minnesota, MS Z.82Z, N.8I, 1. 2720).

29 See Fowler, pp. 45, 54.

30. Annie G. Gilchrist, 'Over Yonder's a Park', Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Number 14 (I910), 59.

31. Marion Bowman, 'The Colour Red in "The Bible of the Folk"', in Colour and Appearance in Folklore, ed. by John Hutchings and Juliette Wood (London: Folklore Society, I99I), PP. 22-25.

32. Moira Tatem, 'Purple: A Tale of Blue Blood and Scarlet Raiment', in Colour and Appearance in Folklore, pp. 47, 49.

33. Child 20D, 20E, 20F, 20N; Child, IV, 45i; Buchan, 'The Maid', pp. I06-07; Bertrand Harris Bronson, The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads with their Texts, According to the Extant Records of Great Britain and America, 4 vols (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959-72), 1, 290 (p. 38); Greig-Duncan, 11, 34 (F).

34. Child, 1, 227.

35 Child, I, 219.

36 Hodgart, pp. 35-37. See also The Idiom of the People: English Traditional Verse Edited with an Introduction and Notes from the Manuscripts of Cecil J. Sharp, ed. by James Reeves (London: Heinemann, I958), p. 3I; Toelken, 'An Oral Canon for the Child Ballads', pp. 93-IOI; Buchan, The Ballad and the Folk, p. 17I; Roger de V. Renwick, English Folk Poetry: Structure and Meaning, Publications of the American Folklore Society, New Series, z (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, I980), pp. 14, 36-37; Wurzbach, 'An Approach to a Context-Oriented Genre Theory', pp. 57-58; Barre Toelken, 'Figurative Language and Cultural Contexts in the Traditional Ballads', Western Folklore, 45 (I986), 128-33.

37 Barre Toelken, The Dynamics of Folklore (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979), pp. 199-223; Toelken, 'Figurative Language', pp. 133-39.

38 Fowler, pp. 268-70.

39 Ballads and Songs of Indiana, ed. by Paul G. Brewster, Indiana University Publications, Folklore Series (Bloomington: Indiana University, I940), pp. Iz8-z9 (A); Patrick W. Gainer, Folk Songs from the West Virginia Hills (Grantsville: Seneca Books, 1975), pp. 68-69; William Wells Newell, Games and Songs of American Children (New York: Harper & Brothers, I884), pp. 75-78.

40. Hodgart, pp. 35-36.

41. Bronson, I, z96 (5S)-

42. Ella Mary Leather, The Folk-Lore of Herefordshire Collected frbm Oral and Printed Sources (Hereford: Jakeman & Carver; London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1911), pp. I98-99.

43 David Buchan, 'Traditional Patterns and the Religious Ballads', in The Concept of Tradition in Ballad Research: A Symposium, ed. by Rita Pedersen and Flemming G. Andersen (Odense: Odense University Press, I985), pp. 29-31. The religious ballads include 'The Maid and the Palmer', 'Saint Stephen and Herod' (Child 2z), 'Judas' (Child 23), 'The Cherry-Tree Carol' (Child 54), 'The Carnal and the Crane', 'Dives and Lazarus' (Child 56), 'Brown Robyn's Confession' (Child 57), and 'The Bitter Withy'.

44. More Traditional Ballads of Virginia Collected with the Cooperation of Members of the Virginia Folklore Society, ed. by Arthur Kyle Davis, Jr. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, I960), pp. 8z-83 (AA).

45 Sharp, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, I, 56-57 (B).

46 Child zoL; Child, V, 211-12; Buchan, 'The Maid', pp. I06-07; Folk-Songs of the South Collected under the Auspices of the West Virginia Folk-Lore Society, ed. by John Harrington Cox (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, I925), p. 30 (C); Traditional Ballads of Virginia Collected under the Auspices of the Virginia Folk-Lore Society, ed. by Arthur Kyle Davis, Jr. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 19z9), pp. 133-34 (A), I34 (B); Davis, More Traditional Ballads of Virginia, pp. 8z-83 (AA); H. E. D. Hammond, 'Conventional Ballads, Love Songs, Sea Songs and Sailor Songs, Miscellaneous Songs, Collected in Dorset', Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Number II (I907), 70-7I, 71; George McIntyre, 'Collector's Piece', Chapbook [Aberdeen], 3, no. z (n.d.), 21; Sharp, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, I, 57-58 (D), 6I (I).

47 Fowler, pp. 63-64. See also Hodgart, pp. 41-42.

48 Child, v, 283-84.

49. See David Buchan, 'The Wit-Combat Ballads', in Narrative Folksong: New Directions: Essays in Appreciation of W. Edson Richmond, ed. by Carol L. Edwards and Kathleen E. B. Manley (Boulder: Westview Press, 1985), pp. 387-88, 395; Buchan, 'Talerole Analysis', pp. 69-72.

50. Folk Songs from Newfoundland, ed. by Maud Karpeles (London: Faber and Faber, 1971), pp. 39-40 (A), 40-41 (B); MacEdward Leach, Folk Ballads and Songs of the Lower Labrador Coast, National Museum of Canada Bulletin, zOI, Anthropological Series, 68 (Ottawa: National Museum of Canada, I965), pp. z6-z9. See Coffin, p. z24.

51 Leach, pp. 26-29.

52 Child, I, 228-29.

53 Hugh Shields, 'Popular Modes of Narration and the Popular Ballad', in The Ballad and Oral Literature, ed. by Joseph Harris, p. 44. See Bronson, Tv, 457 (I), 457-59 (z); Tom Munnelly, 'The Man and his Music . . . John Reilly', Ceol, 4 (197z), 3, 8.

54. Buchan, 'Traditional Patterns', pp. 29, 31.

55. Toelken, The Dynamics of Folklore, pp. zz5-6i; Gammon, pp. 233-34; Barre Toelken, 'Context and Meaning in the Anglo-American Ballad', in D. K. Wilgus and Barre Toelken, The Ballad and the Scholars: Approaches to Ballad Study (Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California, Los Angeles, I986), pp. z9-5z.

56 Hoffer and Hull, pp. 154-57; Phillip J. Resnick, 'Murder of the Newborn: A Psychiatric Review of Neonaticide', American Journal of Psychiatry, iz6 (1970), 14I6, 1419; Michael Tooley, Abortion and Infanticide (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983).

57 Phillip J. Resnick, 'Child Murder by Parents: A Psychiatric Review of Filicide', American Journal of Psychiatry, i26 (I969), 3z8-31; Resnick, 'Murder of the Newborn', pp. 1415-I7.

58 Margaret Sweeney, 'Mrs. Ernest Shope: A Memorable Informant', Kentucky Folklore Record, ii (I965), 21-22.

59. Gladys V. Jameson, Sweet Rivers of Song: A Book of Traditional Songs from the Southern Appalachian Mountain Region (Berea: Berea College, I967), p. 55.

60 Harold W. Thompson, Body, Boots and Britches (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1940), pp. 447-48. See Coffin, p. 45.

61 Songs of the Newfoundland Outports, ed. by Kenneth Peacock, 3 vols, National Museum of Canada Bulletin, 197, Anthropological Series, 65 (Ottawa: National Museum of Canada, 1965), In, 804-05 (A).

62 Ethel Moore and Chauncey 0. Moore, Ballads and Folk Songs of the Southwest: More than 6oo Titles, Melodies, and Texts Collected in Oklahoma (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, I964), pp. 32-33 (A). See Coffin, p. 2zi.

63 Buchan, 'The Maid', pp. I06-07.

64 Buchan, 'Tale Roles and Revenants', p. I50.