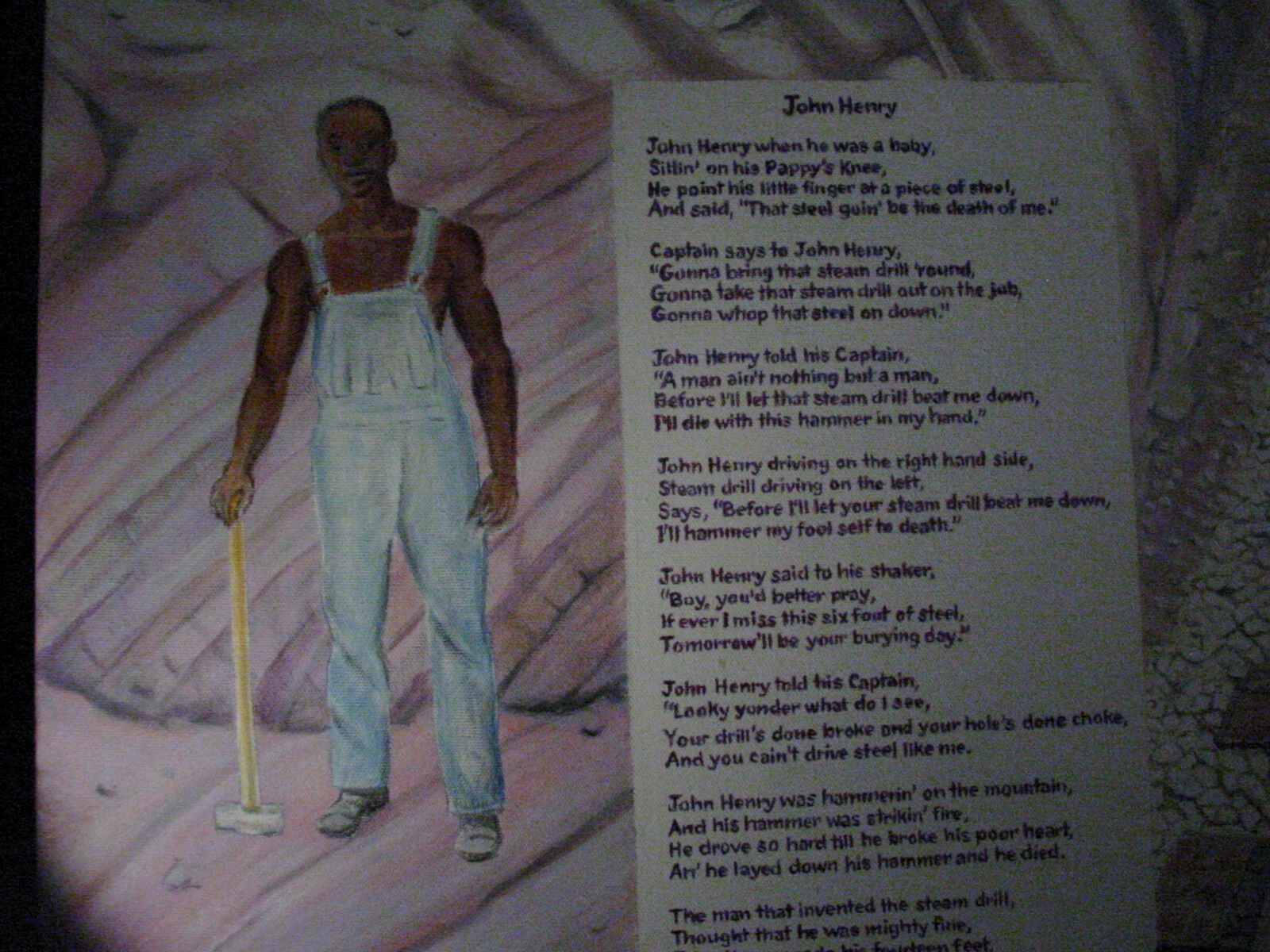

John Henry on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway

John Henry Close-Up with Text

[Guy Johnson (John Henry, 1929) and Chappell both consider the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway and more specifically, the Big Bend Tunnel, as the location of the John Henry ballad.

I favor the Alabama origin as presented by my friend John Garst. For now after the first few pages much of this chapter is raw text- unedited.

R. Matteson 2014]

JOHN HENRY ON THE CHESAPEAKE AND OHIO RAILWAY

A factual basis for the Henry tradition on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad in West Virginia required the employment of hand

labor and machinery together, if not continuously at least on occasion, in its construction from 1870 to 1873. If rock-drilling on the road was done altogether by hand drills or altogether by steam drills, no chance for a conflict between the two kinds of work obtained, and the tradition can have no real basis there. That the opportunity, however, for such a conflict did actually exist has more than legendary support.

In the second half of the 19th century hand labor was employed widely in tunnelling, and in some cases the hand drill was used

exclusively. 1) Steam drills came into fairly general use in the third quarter of the century, particularly in heavy tunnelling, both in Europe and America. On the Mt. Cenis Tunnel they were put "to work in full during 1861", and remained to the completion of the tunnel ten years later. [2) Their next successful use was in the Hoosac Tunnel, where the Burleigh drills were introduced in 1866.[3] In 1870 they were introduced into the Nesquehoning Tunnel, with marked success.[4] From 1872 to 1875 the Ingersoll drills were employed with the Burleigh compressors successfully in building the Musconetcong Tunnel. [5]

About this date hand drills and steam drills were brought together on several lines. Notable among these was the Cincinnati Southern, with twenty-six important tunnels. In some of them hand drills were used in the heading, and in others on the bench, supplemented by steam drills.[6] In actual practice, of course, the two types of drilling were employed together wherever the steam drill was tried out in tunnelling during its period of development, a half-century or more.

Their use together on the Chesapeake and Ohio, at some time between 1870 and 1873, is shown by the testimony of L. W. Hill,

a soldier of the Confederacy, who is better known as "Dad" among railroad people around Hinton, West Virginia, where he was living when he made his report in September, 1925:

-----------------

1) Port Henry Tunnel on the New York and Canada, 1874-76, and Lick Log Tunnel on the Western North Carolina Railway, 1870 were built by hand labor. Tunnelling, pp. 976, 982. In Mount Wood and Top Mill tunnels, built in 1889, "all drilling was done by hand". Journal of the Western Society of Engineers, II (1897), 49.

2) Tunnelling, p. 130.

3) Ibid., p. 165ff.

4) Ibid., pp. 165, 974.

5) Henry S. Drinker, resident engineer of the Musconetcong Tunnel. The Railioad Gazette, VII (June 5, 1925), 228ff.

6) Tunnelling, p. 966ff.

________________________________________

44

I was conductor 35 years on a freight train on the C and O Railroad between Hinton and Clifton Forge. I am now retired and on the pension list of the C and O. I got one of my eyes hurt by a piece of rock flying in it when I was helping to build Lewis Tunnel, which is not far from Big Bend Tunnel just above here on the C and O Railroad. I have been troubled with my eyes ever since, bu't I lost the sight of my best eye first, and now I can hardly see.

A steam drill was used for a while in building Lewis Tunnel, and I ran the stationary engine that furnished steam for it. The drill could be used on a bench only, and was not a success there, and it gave way to the hand drills. Later I ran the stationary engine for lifting rocks in the shaft and pumping water.

In one way or another many people were killed in building Lewis Tunnel: many were killed from careless blasting. There was a graveyard built there along with the tunnel, and one in Big Bend Tunnel too.

Bob Jones was the best steel-driver in Lewis Tunnel, but not much better than some of the others in there with him. They usually sang a song they had composed on their work, or the foremen, or some 'loose' women around the camps. They called one of them Liza Dooley and made a song on her.

This report of the hand drill as the important tool at Lewis Tunnel puts the type of drilling there in line with that employed generally on the road. A newspaper of the state gives "from Big Sandy to White Sulphur, a distance of at least 200 miles, the clink of the drill-hammer heard from early in the morn to eve."[7] The published official records of the road make no exception to the general use of hand labor in that work. [8]

Mr. Hill's connection with ,machine-drilling on the road is highly significant. With the steam drill established in tunnelling by 1870, and the general airing of its marvels in engineering journals and local newspapers, [9] those responsible for the extension of the Chesapeake and Ohio across West Virginia could not escape giving it a trial. The belief of Shanley, the contractor of Hoosac Tunnel, that the expense of hand labor there would have been ('fully three times the cost of machine-drilling [10] to; and Hoosac Tunnel was well on toward completion by 1870, could not be ignored by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway whose bonds were being sold on Wall Street.[11] Their report indicates full use of all up-to-date methods:

Beyond the great want of trained mechanical labor at that time in the Southern States, the tunnel experience upon the work of the several lines consolidated into the Chesapeake and Ohio cannot be said to have departed

-----------------------

7) Wheeling Intelligencer, Wheeling, W. Va., Oct. 3, 1871

8) Tunnelling.

9) Wheeling Intelligencer, Dec. 30, 1870. Lynchburg Daily Virginian, Sept. 22, 1871.

10) Tunnelling, p.244.

11) The Weekly Register, Point Pleasant, W. Va., March 3, 1870

______________________________________________

45

materially from the routine of construction of other first-class mountain roads of the same period. [12]

Everything favored the introduction of steam drills on the road between 1870 and 1873. Through the development of the compressor system at Mt. Cenis Tunnel, their successful use in tunnelling had been noted in Europe for nine years. They had been used with marked success for four years in the Hoosac Tunnel of Massachusetts, and had just been introduced with great promise into the Nesquehoning Tunnel. They were therefore a necessary part of the equipment for building first-class mountain roads of that period.

That steam drills were actually used at Lewis Tunnel, as reported by Mr. Hill, is shown by newspaper accounts during 1871. In January of that year, the Richmond Dispatch noted that "at the Lewis Tunnel, or Jerry's run, the contractors have put the steam drills in operaion". [13] In November following, Charles Nordhoff, formerly editor of the New York Post, who at the time was making a trip along the Chesapeake and Ohio across West Virginia and writing a series of letters on the progress of work on the road, referred to Lewis Tunnel "in which several of Burleigh's drills are at work".[14] These records cover a period of practically nine months.

Both types of tunnelling, thin, were employed together on the road between 1870 and 1875; thus satisfying the major requirement as a factual basis for the Henry tradition in its construction. That innovations of this sort among hand labor would be followed by drilling-contests between the old and the new was the thing to expect. That such a contest, the basic episode of "John Henry," actually took place as celebrated in popular report has every reasonable influence from these circumstances in its favor, and should not require much further evidence for its authenticity.

If the steam drills put to work at Lewis Tunnel in January, 1871, were the Burleigh drills mentioned in November of that year, and were operated continuously for almost nine months, Mr. Hill would seem to be in error; but he has the support of the chief engineer of that work, that they failed: "subsequent to War, Burleigh rock-drill tried in the tunnel, but unsuccessfully." [15] This statement not only establishes Mr. Hill, who had a part in testing the machine, but throws damaging light on the assumption that the steam drills mentioned in the Richmond Dispatch as having been put to work at the tunnel in January were the Burleigh drills, referred to by Nordhoff in November following, and favors the inference that several steam drills were experimented with at Lewis Tunnel, those

-----------

12) Tunnelling, p. 484.

13) Jan., 21, 1871. The Richmond Dispatch is in conflict with the Chesapeake and Ohio "records that steam drills were first introduced in construction on Lewis Tunnel the latter part of April, 1871." John Henry p. 49 Dr. Johnson states in his next paragraph that the C and O files of reports from their engineers and contractors of this period have been destroyed by fire.

14) New York weekly Tribune, Nov. 8, 1871.

15) Tunnelling, p. 965.

_____________________________________

46

mentioned in January and November, and possibly in April, and very probably others before and after these dates.[16]

It follows that the steam drill in all probability was tried out elsewhere on the road at the time, and Big Bend, the largest tunnel on the line, had certain advantages to offer. The rock of Big Bend was different from that of Lewis Tunnel, [17) and different results might have been expected from the machine, with the promise of a larger number of sales upon its adoption there.

So-called documentary proof for the steam drill at Big Bend Tunnel seems not to exist. The only possible reference of the sort known appears in an account of the work there about the tirm tunnel was completed: "Unavoidable contingencies, such as f:a

breaking of machinery, &c., have delayed this part of the work considerably." [18] That breaking of rnachinery" can have such \"i rttr

very doubtful. It would mean too great reliance on the stear

to accord with known facts. In the absence of anything bet's

an understanding of the circumstances at Big Bend, testimonirl

must be allowed.

Neal Miller,le) son of Andrew Jackson Miller, a nafir'e :c

community, lives about a mile up Hungart's Creek, which joins'r;

brier River at the east end of Big Bend Tunnel. He was a mem,m

a large family. Three of his br,others {(followed" the railroad

are on the Norfolk and lVest'ern, one an engineer and the ,--rud"

painter. The third was an engineer on the Chesapeake anc

Railway, and a few years ago "his train al'most smothered n,rc

death in Big Bend Tu,nnel," with the result that he died abcu:

months later. In his neighborhood Neal Miller is regarded as

a good memory and being honest.

Mr. Nliller says that he worked in Big Bend '{off aE';

carrying water and steel for the workimen, and knew John Henrt

I saw John Henry drive steel in Big Bend Tunnel. He u'as t

singer, and always singing some old song when he was driving ste*1"

was a black, rawboned man, 30 years old, 6 feet high, and weigh*r

200 pounds. He and Phil Henderson, another big Negro, but not i:

were pals, and said that they were lrom North Carolina.

Phil Henderson turned the steel for John Henry when he 'i::vtw

the contest with the steam drill at the east end of the tunnel Il

Henry beat the steam drill because it got hung in the seam of the rock and lost time.

Dave lifithrow, who lived with his wife at our home, was the in charge of the work on the outside of the tunnel where John Henry

-----------------

16) Such was the experience at Hoosac Tunnel. The Brooks, Gates, and Burleigh machines were introduced there in June, 1866, and replaced by the Bu'rleigh drill in November following. Tunnelling, p. 159ff. About 10 of these machimes were discarded at Hoosac. Did the manufacturer try to sell them in the South?

17) Tunnelling, p.965.

18) The G,reenbrier Independent, June 1, 1872.

19) C. S. ("Neal") Miller, Talcott, W. Va.

_________________________________

47

beat the steam drill, and Mike Breen was the foreman on the inside of the tunnel there.

The steam drill was brought to Big Bend Tunnel as an experiment, and failed because it stayed broke all the time, or hung up in the rock, and it could be used only on bench drill anyway. It was brought to the east end of the tunnel when work first commenced there, and was never carried in the tunnel. It was thrown aside, and the engine was taken from it and carried to shaft number one, where it took the place of a team of horses that pulled the bucket up in the shaft with a windlass.

John Henry used to go up Hungart's creek to see a white woman, --or almost white. Sometimes this woman would go down to the tunnel to get John Henry, and they went back together. She was called John Henry's woman around the camps.

John Henry didn't die from getting too hot in the contest with the steam drill, like you say. He drove in the heading a long time after that. But he was later killed in the tunnel, but I didn't see him killed. He couldn't go away from the tunnel without letting his friends know about it, and his woman stayed 'round long after he disappeared.

He was killed all right, and I know the time. The boys 'round the tunnel told me that he was killed from a blast of rock in the heading, and he was put in a box with another Negro and buried at night under the big fill at the east end of the tunnel. A mule that had got killed in the tunnel was put under the big fill about the same time.

The bosses at the tunnel were afraid the death of John Henry would cause trouble among the Negroes, and they often got rid of dead Negroes in some way like that. All the Negroes left the tunnel once and wouldn't go in it for several days, some of them won't go in it now because they've got the notion they can still hear John Henry driving steel in there. He's a regular ghost 'round this place.

His marks in the side of the rock where he drove with the steam drill stayed there awhile at the east end of the

tunnel, but when the railroad bed was widened for double-tracking they destroyed them. 20)

The Hedrick brothers, George, seventeen, and John, twenty-three were living with their father within a few hundred yards of

Big Bend when work began on the tunnel in 1820, and remained there while it was under construction. George still lives there, but for the last few years John has lived with his daughter's famify in Hinton, eight miles west of the tunnel. [21]

George Hedrick says that he did no work in the tunnel, but that he continually around where the men were at work, and knew,

"what was going on":

My brother John helped to survey the tunnel and had charge of the woodwork in building it. I often saw John Henry drive steel out there. I saw the steam drill too, when they brought it to east end of the tunnel,

------------------

20) Mr. Miller made his report in Sept., 1925.

21) The testimony, of George Hedrick, Talcott, W. Va., was obtained in Sept., 1925, and that of John Hedrick. Aug. 1927. The latter was visiting his son in Kentucky when I made my first trip to the tunnel in 1925.

_______________________________

48

but I didn't see John Henry when he drove in the contest with it. I heard about it right after. My brother saw it.

My memory is Phil Henderson and John Henry drove together against the steam drill. That was the usual way of driving steel in the tunnel.I saw John Henry drive steel. He was black and 6 feet high, 35 years old, and weighed 200 of a little more. He could sing as well as he could drive steel, and was always singing when he was in the tunnel...

'Can't you drive her, - - huh?'

The Hedrick brothers are sober men of good practical sense and judgement. George is about six feet tall, stands erect, and weighs around two hundred pounds, and must have been a superior man forty years ago. John is not quite so tall, but has a larger frame and muscle. He was twenty-three when the tunnel was begun,- and was unquestionably will fitted for a responsible job among the gangs there. He speaks with the authority of a tunnel boss:

I was manager of the wood-work in putting through Big Bend Tunnel and built the shanties for the Negroes there in the camp. The first work at Big Bend Tunnel was making the survey, and I helped with that. Then men came to put down the shafts, and took rock from them 50 feet down to send away for contractors to examine when they were making contracts for the work on the tunnel. Menifee put down the first shaft. Whne he came I went with him to help him find the place. I worked there till the tunnel was all completed.

I knew John Henry. He was a yaller complected, stout, healthy feller from down in Virginia. He was about 30 years old, and

weighed 160 or 170 pounds. He was 5 feet 8 inches tall, not over that.

He drove steel with a steam drill at the east end, on the inside of the tunnel not far from the end. He was working under Foreman Steele and he beat the steam drill too. The steam drill got hung up. But Henry was beating him all the time. I didn't see the contest, because it was on the inside of the tunnel, and not very many could get in there. I was taking up timber, and heard him singing and driving, and he was beating him too.

John Henry stayed 'round the tunnel a year or two, then went away somewhere. I don't remember when he left. He had a big black fellow with him that drove steel, but he couldn't drive like John Henry. John Henry was there 12 months after the contest. I know. He was there when the hole was opened between shaft I and 2. Henry Fox put the first hole through, and then climbed through it. He was a and got the watch that Johnson offered for the first man to get through. He was from shaft 2, and people on the other side pulled him through and tore off all his clothes.

I don't believe a single man got killed at Big Bend Tunnel at work. A boy fell in the shaft, and one died from foul air. A man

in Little Bend Tunnel, [22] but none in Big Bend.

These three witnesses are giving direct testimony, not popular hearsay reports. They are not ballad-singers and general reposi-

-------------

22) A tunnel on the line a short distance west of Big Bend Tunnel.

____________________________________

49

of oral traditions, but represent the stable citizenry of a conservative community. In a court or forum of that locality, they would have the support of good character and general reliability in matters of dispute coming under their observation.

The explanation Mr. Miller makes of the steam drill at Big Bend the subsequent use of the engine from it recalls Mr. Hill's experiences with the machine at Lewis Tunnel. His account of John Henry's death and burial is of a hearsay character, and has only the value of a report at the time. He is not alone in making this report, however, and his account of the tragic tone of the place will seem more real eventually. Mr. Miller is no apologist, and no hero-worshipper, for John Henry or anybody else, as his testimony indicates. He has the characteristic mountaineer attitude toward the Negro, and regards the famous steel-driver as rather vicious, "just another Negro", superior of course and able to claim his woman when he was present, but remembers that he was not always present. His reference to Henry's woman as "almost white" was but a cautionary after-thought to temper the blow "white woman" for the moment and has no other value in his report. Later he talked motre

about the woman, whom he knew for several years. She lived

ru lurtle house about two miles up Hungart's Creek, and often ,made

trips visiting construction camps, usually of minetrs, along the

. Confir'mation of this account may be had from G. L. Scott,

sly mentioned, who remembers her house, her name and fame,

dre man who '{stood her" at Big Bend Tunnel. 13)

ln his statement that John Henry sang "Can't you drive her,

--huh?" George Hedrick makes a good claim for his acquaintance

with the steel-drivers at the tunnel, and for the correctness of his memory. A few months after Big Bend was completed, the line

----------------

23) Of M_orton says of Negro slaves in Monroe County, which

teo the_Big_Bend community at the time the tunnel was begun: "The servants in the 'bighouse' looked down on the fiield hands. but both house and field servants looked down on the poor class of whites." A History of Monroe County, p. 185ff.

In 1878, Page Edwards, a Negro living at Big Bend Tunnel, became

jealous of. his wife, a "bright mulalto woman of-handsome app'earance," and killed her. In 1907, Elbert Medlin, born irn the larger- Big Bend community about the time the tunnel was under construction, killed his wife because she seemed to prefer the other man. Medlints father was a light mulatto., and his mother a "white woman of low and degraded insticnts." They claimed that they were married in Ohio. J. H. -Miller,

History of Summers County, pp. 788,802.

Anne Royall, a native of Monroe county, gives an example of a family rmme girls over i'n Virginia- having children by Negro men, and adds from her "poor ignorant driver" of the coach, "There were several instances of their having children- by- black .men.', Sketches of History Life and Manners in the United States (1826), by a Traveller, p. 30ff.

For the race problem in Virginia, see_J. H. Russell, "The Free Negro in Virginia," 1619-1865," Johns Hopkins University Studies

Historical and Political Science, XXXI.

_____________________________________

50

"Can't you drive her home, my boy?" was published as having been sung by the miners in building the tunnel. [24]

John Hedrick makes even a better claim for his memory of the tunnel. He is correct in saying that "Menifee put down the first shaft," and in Menifee's purpose in doing it.[25] Building shanties for the workmen, surveying, and sinking shafts for rock to be us in contracting for its construction characterize the first work at tunnel, facts that will not be questioned. Fox [26]) and Steele [27] were foremen at the tunnel, and the former was in charge when the opening was made from shaft one to shaft two, as Mr. Hedrick states. Testimony of this sort is not altogether hearsay stuff, and

hardly be denied value in showing the employment together of t

two kinds of labor at Big Bend. These men are certain that

saw the two types of drills at the tunnel, and that a contest t

place between them. Their evidence is of about equal value.

In their statements for Henry's presence, they are supported

two other witnesses, George Jenkins and D. R. Oilpin, who dr

that they worked in the tunnel. These two men were not there wl

the tunnel was begun, but came later and saw less.

Mr. Jenkins ze; says that he is a native of Buckingham Cou

Virginia, that he went with his father, a blacksmith, to Big

soon after the tunnel was started, that he worked at first as r'ti-,

boy", and that later his father got him a job in the shop to "sh

steel and other toolstt:

John Henry was there when I went to Big Bend, and I remern

he was under Jack Pasco from lreland. He was very black, and hetd w

about 160. Always singing when he worked. He was a sort of song-lea

He was 30 or 35 years old.

I don't know what he did when he wasntt at work in the

I don't know when he left the tunnel or where he went. No; I cj

know anything about him driving steel against a steam drill" The t

was all hand work.

Jinr Brightwell ran the hoisting engine at shaft 2, and my brother fi

for him. Captain Johnson gave a barrel of liquor when they knoc

through the heading from shaft 2 ta 3. Mose Selby stabbed John i-1

that day, but didn't kill him. I saw Hunt in Roanoke a few years

I saw o,ne man killed in the tunnel. He was taking up bottom r'

a rock fell from overhead and killed him dead. I dontt remember w

they did with him, sent him home to his people I suppose.

-----------------

24) The Mountain Herald, Hinton, W. Va., Jan. 1, 1874.

25) The Greenbrier Independent, Jan. 22, 1870.

26) The Railroad Gazette, Nov. 2, 1872.

27) John Henry, p. 30. Dr. Johnson quotes from Border

Watchman. I have not been able to find the files of this newspaper but other newspapers of the time often quoted from it.

28) Testimony of George Jenkins, 75 years old, of Montgomery, W. Va., was obtained in Aug., 1927.

____________________________________

51

Then the mules came out of the tunnel some of them were blind as as a bat. One went blind and stayed blind. Most of them got all right after a day or so. They put a cover over their heads for a while.

They burnt lard oil and blackstrap in the tunnel for lights.

After Big Bend was in I flagged on the work train between White Sulphur and Hinton about a year. Then I went with my father to work on a tunnel at King's Mountain, Ky. No; I knew John Henry only at Big Bend I don't know what became of him.

Mr. Gilpin [29] is on the pensiron list of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway. He came to Big Bend, he says, from Knoxville, Tenn., with his father, a well-digger who had been successful in several states

rte South before the Civil War in sinking wells through rock undr

. His father was br,ought to the tunnel by Johnson, contractor,

eff,orts to put down shaft one had been checked by water

mg in it, and 'remained as a sort of boss or director of drilling

blasting in the heading.3o) Mr. Gilpin says that he worked

with his father, carrying water and steel for the workmen.

He remembers John Henry, and describes him as black, about

feet tall, and weight ((as ,much as 200 pounds, but not fat", with

rrvL Lsut

fo* lips and the prettiest set of white teeth I ever looked at". He

that Henry, like the others, usually kept his shirt off when he

in the tunnel:

I know that he was from North Carolina, for he used to get Pearce,

brother-i.n-law and a foreman in the tunnel, to write letters for him

his people there. Pearce liked John Henry because he was sensible

used good manners, and keen and full of good jokes, and he could

and pick a banjo better than anybody else I ever saw.

lly mother used to help out when anybody got hurt in the tunnel.

rd come with clean cloths and medicine. She ran a bearding house

at the tunnel, and baked bread for John Henry. He cooked the

of his food at the camp, but he couldn't bake bread and Pearce asked

mother to do it for him. I'd often carry it to him at his camp, and

give me a little extra for carryiing it.

Inve seen John Henry playing cards, but I never saw him gambling,

he didntt swear like the other Negroes did when he was at work.

-\{y half-brother, Jim Wimmer, drove steel in the tunnel, and he drove

flfr John Henry when he could get the chance, because John Henry ivas

Spod worker at driving steel, and he was sensible and safe, a man

Eood judgment, with a good eye. There was not so much danger

ium fiving with him in the heading like there was with some of the other

rrffirrfiF"Ers. John Henry lvas a reliable man in danger or in a risky job.

Vher: the lirst light hole was opened trom shaft number one to the

rffi end of the tunnel, I dipped the liquor for the steel-drivers. Every crew tried to put their boss through the hole first, and they fought and

-----------------

29) Testimony of D. R. Gilpin, Hinton, W. Va., was obtained in Sept., 1925.

30) John Gilpin is remembered in the Big Bend community as a "good driver."

________________________________________

52

yelled like mad men. John Henry was a mighty powerful man that day. I tell you when they pushed my father through the hole, they pushed me through after him, and almost tore off one of my legs in doing it. Then Superintendent Johnson gave me a suit of clothes because I got hurt.

I don't know a thing about John Henry driving steel in a contest with the steam drill, and don't think I ever saw one at the tunnel. Hand drills were used in the tunnel. They were using an engine at shaft number one to raise the bucket up when we moved to the tunnel, but they didn't have any steam engine or steam drill in the tunnel.

Thc last time I saw John Henry, who was called Big John Henry,

was when some rocks from a blast fell on him and another Negro. They were covered with blankets and carried out of the tunnel. I don":

John Henry was killed in that accident because I didn't hear of hi:

buried, and the bosses were always careful in looking after the

and dead. They were afraid the Negroes would leave the tunnei

I don't know what happened to John Hen,ry after that accidenr. :

He may have left for a while and then come back again, but I ::::

I always thought John Henry died in the tunnel, but I didn't kno*' :-r

about his death. I don't remember seeing John Henry after the :; r

rocks fell on him. I might have found out what happened to hirn -:

tried then, but we were not allowed to go round the camps

questions about such things. Any man who walked around and talk:-:

the hard life in the tunnel was allowed to stay there about t1., :

and thatts all.

Mr. Gilpin remembers that Henry was the "singingest man I ever saw," but remembers only a few stanzas of his song:

Tell the captain, - huh, I am gone, - huh,

Tell the captain, - huh, I am gone, - huh,

Tell the captain, - huh, I 'am gone, - huh,

Big John Henry, - huh,

Big John Henry, - huh,

Big John Henry, - huh,

Seven others were built in the same style on these lines: "The captain can't get me", "Shoo fly up, shoo fly down," "Shoo fly all 'round the town," "This old hammer a-singing," "This old steel a-ringing," "This old sweat a-rolling", and "I am getting dry". Mr. Gilpin says that John Henry always sang "I am getting dry" when he wanted water to drink, and that as water boy he was supposed to carry it. Henry used the "huh", or grunt, to mark the strokes of his hammer.

Mr. Gilpin says he got his education at Big Bend tunnel. He talks enthusiastically on Big Bend Times as Confederate soldiers often do about the Civil War. Unlike Mr. Miller, he is a hero-worshipper and John Henry and the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway are his heroes. He once looked at a picture of Jack Johnson, the Negro prize fighter, with full chest and muscled arms and saw only his John Henry of Big Bend days, just as the Confederate veteran saw only his comrades of 1860 in the marching brigades of 1917. He has kept several little reminders of his connection with the road

___________________________________

53

and takes pride in wearing its service pins. Big Bend is at the heart of his world, and he knows the place well.

He knew the two doctors who lived at Big Bend at different times while the tunnel was under construction, their families, and not a little of them afterwards. He remembered accurately a surprisingly large number of the foremen and other officials at the tunnel. He knew the engineer who drove the first train through the tunnel, and said his name was South Mack, who is not infrequently remembered in the locality as Seth Mack. He explained how Mack lost his thumbs, by inserting them into a break somewhere in his little engine, after turning it over and getting caught under it, to check the escaping steam to keep from being rrscalded to death" before he could be rescued.

The reason Mr. Gilpin offers for Johnson's bringing his father to Big Bend is plausible enough. Water rising in the tunnel was on

the difficulties the engineers had in building it [31]. He may not have dipped liquor for the men when they opened up the tunnel from shaft one to the east end, but very probably somebody did. The water boy was the proper functionary when liquor became a substitute for water, and it was used freely on such occasions there [32]. The Border Watchman leads one to believe that Mr. Gilpin could have reported a casuality list on this occasion: "We learn that the hands on the East appr'oach to Big Bend Tunnel and those driving the 'heading' east fnom Shaft 1, having knocked out the rock between them, tried to knock out each other. Several parties were severely stabbed [34].

The song "Shoo Fly" was widely sung on the minstrel stage of early seventies. A Virginia newspaper observed: "Many persons

are not in the habit of frequenting negro minstrel shows have expressed a desire to know what are the words of a song to which reference is so often made in the newspapers, and the chorus of which salutes the ear in every public place. It is a nonsensical medley without rhyme or r&s,on immensely popular with the masses." 34] The Governor of West Virginia was reported as singing a part of the song when he "Broke Ground on the C. & O. R. R." in that state.[35) Moreover, "miners hoarsely singing," and "sweat a-rolling" belong to the education of Mr. Gilpin at Big Bend. Such echoes, although some of them may not be factual, suggest that he is not entirely a man of fiction.

On my first trip to Hinton, in 1925, I mentioned "John Henry" Mr. Gilpin, without pointing out specifically any of its details,

but he seemed not to know the ballad. He remembered, with difficulty,

---------------

31) The Greenbrier Independent, Jan. 28, 1871, gives an

account of the use of sumps and pumps to keep the water out of the tunnel.

32) John Henry p.5.

33) The Greenbrier Independent, Feb. 19, 1872.

34) The Staunton Spectator and General Advertiser,

Feb., 1. 1870.

35) Wheeling Intelligencer, April 18, 1870.

_____________________________________________

54

only a few stanzas of the steel-driver's song. On a second visit about two years later, I again introduced the ballad, and characterized it rather fully. Mr. Gilpin commented thus: "John Henry was always singing. He wouid sing about his woman, giving her his hammer, wrapping it in gold, gold at the White House, and giving it to his woman, sitting on his mammy's knee, watermelon smiling on the vine, tell the captain I am gone, and like that." But he did not reproduce a single stanza of the ballad, and seemed not to be able to.

The question of Henry's woman had been raised, but no mention made of the White House, although allusion to it is found in several texts of the ballad. And "gold at the White House" is unique in the tradition. He explained: "The White House is where the President lives. John Henry and the other Negroes there in the tunnel used to sing about it, and about going there. They used to sing about Fred Douglas up there too."

He knew Henry's woman, and several others equally important in building the tunnel, and contributed rather full accounts of Lu - - -, Liza Ann---, Kate--, and one called "Liza Dooley", but though this not her real name. Some of them claimed to be half Indian One had long, straight, black hair, and another red hair. One was a fortune-teller and banjo-picker, a woman of unusual vivacity,a sort of pagan beauty, who played at dances and on other occasions of jolification, not infrequently for slightly mixed crowds. He remembered the following stanzas from her singing:

I'm going down to town,

I'm going down to town,

I'm going down to Lynchburg town,

To carry my baccer down.

Baccer selling high,

Selling at a dollar a pound,

And nobody wants to buy.

I pawn my watch,

And I pawn my chain.

Oh go 'long Liza, poor gal,

Poor little Liza Jane.

Up old Liza, poor gal,

Up old Liza Jane.

Up old Liza, poor gal,

Up old Liza Jane.

She lost her lover

And found him again.

Up old Liza, poor gal,

Up old Liza Jane.

She lost her lover

In the bottom of the sea.

Up old Liza, poor gal,

Up old Liza Jane.

____________________________

55

She lost her lover

In the bottom of the tunnel,

Up old Liza, poor gal,

Up old Liza Jane.

She lost her lover

Gone up on the train.

Up old Liza, poor gal,

Up old Liza Jane.

She lost her lover

Died on the train.

Up old Liza, poor gal,

Up old Liza Jane.

Mr. Gilpin accounted for "tunnel" of the seventh stanza as a reference to Big Bend. He is not the first to report "mixed crowds" fur railroad and mining communities in the South right after the Civil War, but they were not always peaceful assemblies. [36]

The earlier and later refiorts by Mr. Oilpin were essentially in agreement on all points repoited the second time, with one exception. He explained thaf Pearce himself did not write the letters for John Henry to his people in North Carolina, but got Mr. Gilpin's sister, whom he later-married, to write them for him. Such a conflict means nothing. I am not inclined to regard as serious such a conflict in the testimony of an individual witness, nor even greater differences among these five witnesses for Henry's existence. They are white citizens in good standing in their respective communities, and their conflicts have value in showing their independent testimony. [37] George

,r-tkins agrees with John Hedrick in placing the steel-driver's weight

rlrmund 160 pounds, -but differs with him on the question of color.

tr agrees with George Hedrick and Neal Miller as to that. After

,nm,oe -than fifty yearsl confusions in their minds are quite possible,

iurfum*:st certain. Ttrey have told their tales over and over again for

iu h,alf-century, and repetition fro:m memory does not always make for

,ilmsrracy of detail. Recall William Lawson of sacred memory. Another

merioi man at the ti,me or since may have contributed to Henry's

---------------

36) A circus was scheduled for White Sulphur Spri,ngs on the road

near the line between Virginia and West Virginia, while Lewis Tunnel was being built just across the"line in Virginiq, but owing to. a. railroad accident

:irc inimals"did not anrive. A report at the time says:'rThg_people pogre.d

n :rom twenty miles around arid were a sight to see.- Tltgy bor-e their

oinappoi,ntment" bravely Th. banjo was 'plcked', and white and black

midO together. Some drinking and some fighting of course occurred."

The Fredericksburg News, Oct. 10, 1872.

37) Neal Miller was "present and appeared rather chagrined when George Hedrick stated: "My memory is Phil Henderson and John Henry, drove together against the steam drill."

37) Ned Brown, a yellow Negro of Gordonsville, Va., has the reputation around home of being a great lteel-driver, and says that he helped to double-track the road in the eighties between Big Bend Tunnel and Hinton, and that there and elsewhere- he was called the "second John Henry" because when drilling dn the bench he "tore the steel all to pieces."

________________________________________

56

color or stature. [38] Undoubtedly they differed from the first on some important particulars. One is glad to find that they agree on such matiers as the use of hand drills at the tunnel, and John Henry himself, his name, race, and prowess as a gang-leader, a great worker and singer.

The hand drill has already been established as the important tool on the road, and was, of course, a commonplace at Big Bend, where almost everybody drove, sharpened, or carried steel; and the carriers, boys such as Miller, Gilpin, and Jenkins, made a large group, working either continuously or "off and on." [39]

The testimony shows that Henry was well known at the tunnel

and, most important, that he was well fitted for his popular role , a young man, powerful and generous. The witnesses agree that he

did not die immediately after his contest with the steam drill, although an ending of that sort was quite possible, [40] that he was at the tunnel from first to last, or rather until it was well on toward completion, and that they do not know what became of hi'm. -\t:

Mill'er and Mr. Gilpin, however, seem to think that Henry died in tit

tunnel, possibly from blasting in the heading.

Although for seve,ral years the steam drill had been establishel

as a mechanical triumph in heavy tunnelling, and was having- a ni::*

month trial at Lewis Tunnel, it was not a iommonplace of the rc an

certainly not of Big Bend Tunnel, even if the second and thrt

machines were e*pe"-itented with there, and naturally ev-erybodt' w e":

not expected to see it. The time necessary for such a trial would h' l:

been short, pe'rhaps an hour or two, and the observer at the tun:*-

for the r*miindei of the two and a half years of its constructi - r

provided the're was no second exhi,bit, would have had only the ha:r

drill to 'report.

---------------------

39) That carrying steel at Big Bend furnished employment for a large numbe'r of carrieri intinuously ituy be shown by the experience at the Hoosac Tu,nnel, where the rock was similar i,n hardness to that c'l :ln i

gend. In six months, from April 1 to November 1 of 1865, befor-t -tq

nuiGigtt drills were i,ntroduced into the-trtnnel,-in one- h91-d!rS alone.11r l*l'

AiitGivere dullecl (Tunnetling,n.237\, making 19,545 in a single i::'*"7

or 750 a day. There were threE shafts sunk in -digging .Big Bend T'-:::*

itunn ellin s. 965). with a heading east and onE-west fiom each i'i*

ind one from'iach "rid of the tunnel. Provided the experience in dr"''*-i

the headi,ng at Big Bend was similar to that at Hoosac-,- an4 it couli -'i"rl

have di{feiid a sieat deal i,n the. matter of dulling drills, the numb.: -

Aiittu liken;n a-nA out of the "1sht headings of ilig Bend Tunnel :ai'r'

was approximately 6,000. Add ari equal number for ,the bench, 3nc -;

total nrimber of drilis is above 12, 000 to be carried in and out cf :''r

tunnel daily. The drilts were of various lengths, from two to 72 or 1{ ':':i

To tra,nsport from the blacksmith to the diiller and from the driller I a:u

to the biacksmith half of the nossible nurnber of such drills at Bis E;rr:

was a task for all the.neighborhood boys and several others. The stal.*"'-"

that the "employees number about 900 men and boys" at the Hoosac Tunnel (Journal of the Franklin Institute, XCI(1871). 148) indicates that boys were used in that tunnel for such work.

40) For an opposite opinion, see John H. Cox, Journal, XXXII, 511.

_______________________________________

57

Big Bend was a mile and a quarter long, [41] the longest tunnel in America at the time of its completion, and was worked at five different points, with only one chance in five, therefore, that an employee there would see the machine without making a trip for that purpose, and certainly the occasion of a drilling-contest would not have been used to distract workmen from their regular duties. In fact the management in all probability would have been reluctant to advertising the drill at the tunnel. With its failure, the contractor would have realized his greater dependence on the steel-drivers. He and his engineers, with experiences of the Civil 'tMar fresh in their minds' knew the value of keeping up the morale of the men; and

construction gangs of the early industrial south, the period

obse'rvation, were not established, and employers never knew

. far they could rely on them. The failure, ihen, of Gilpin and

ins to see the steam drill at the tunnel, o,r to- remember that

ing was said about it at the time, would seem to have no

ive bearing on the qu'estion of the machine.

The fact that the three who give evidence forr the machine were

ot Big Bend when work began there and that the two who failed to

re it came later is significant. The Hed,ricks place the steam drill

ail the east end of Big Bend early in its mnslru,ction; Neal Miller

rynges, and explains that the engine from the driil was taken to

uhrft one, where oilpin found it when he arrived. While the tunnel

lpT b.egu,1 in January, 1870, rz; the oilpin family came later, on

iilimritation by lhe contractor, after difficutties in drilling had develbped

fi"T water, almost certainly not before the fall of 1g70, and possibly

irn late. as Janu,ary, 1871, when drilling was definitely checked bi

lfuel, and found Henry there when he arrived. Moreover, he-worked

rmnd shafts two and three at the west end of the tunnei. The east

mnl i5 in close proximity of oreenbrier River, down which much of the

rryipment for building the tunnel was brought on bateaux, and the

rnunr was the only. available sou.rce for the ariount of water necessary

lfrb operate the drill at the least expense. The east end of Big Bend

;d the early days in building the tunnel were the l,ogical plice and

to test the machine. on the questi,on, therefo,re, of ttre steana

the later comers, Gilpin and Jenkins, instead of being in ,erious

rdict with Miller and the Hedrlcks, actually support ttem.

Mr. Mille'r and the Hedricks are certain itrat'ttre drilling-aontest

,rnuurred, and their conflict as to the exact spot is not very important

m' ln understanding of the east portal of the tunnel shows. Miller says that the contest was on the outside and John Hedrick that it

--------------

41) As a result of a big fall in the heading at the west end of the tunnel an- open cut was male from shaft three-to the west portal. -

42 ) Menifee Put. down the first _shafts to prepare the tunnel iot .on-

PE.early in -1870 "Green bri e r Independent, Jan. 22, 1870, ;d

W the last of March of that year Johnson liad-the'."*tt".t'to 'Uirifa The Rockingham Register. March 31. 1870).

43) Richmond Dispatch, Jan. 21, 1871.

_________________________________

58

was on the inside, but they agree that it was near the end, or rather that it was in the mouth of the tunnel. The approach at the east portal was an open cut io1 several yards, [44] with a deep valley at the foot of the mountain until it was -filled from the excavation of the tunnel. A contest staged a few feet on the outside and one a few feet on the inside would have been about equally tri$a-e1 from a lar:l:

ciowd of spe.t"tot.. Popular belief in a itafue of Henry, with L*;

hammer in his h;;4, at the end of Big Bend seems to be a developmerr

in orut tradition from the steel-driver's "marks', reported by. Mille:

and to favor u point on the outside of the tunnel as the exact locati:'r

of the drilling-contest.

Johrr Henry, the steam.drill,_un+. the drilling-contest at Big Ben:

stand or fall tog.lt*t, their auihenticity depends on the same dat;

That hand laboi and machinery were 6rought together on,the rrri

is shown fy testimoni*t and _dbcqmentary accounts. Tlll l,h?"^*:::

"rt""iry'lrd;gil' t"tefitet - 1t Big. . Bend, re sulti ng .i n .1, - :oL*.*-*::: :t

H;;'";d ;il"riei* arnr, is ?irecil{. ruqpolted only by. testimo;'

'.t,-t--^^ ^-l L:^ ^n6ts

ii;ilid; ; d"curnentary sort for ihe iteel-driver and his contest

is known to exist.

No adequpte account,nothing detailed and comprehensive of the

construction of tft. Cn.sapeake ind Ohio across West Virginia h i::

;;;;- fuUfi.ft.O, and none can be published from known record';

th; i Lrg. UoOy" tt neglected history belongs Jo." th:. construcl: : r

of the road from'nig Ben? Tu,nnel to kanawha Falls, the sestion :ii

the New River *u-n tiy, a forbidding wilderness, seems ob'i'ic'ui

Euun u slight u.q*iniu*e with buildiig the r'oad in this region :i

zufficient t6t unOittiunOing the inadequite press account of the w: :r

there.

This New River country was characterized at the time as the "t'::"

pid *ild.rn.rs,;;;i- and the d'primitive.wilderness".46) In- 1870 1:"r:

frontier character lot West Virginia had been little changed from \t'!'!r

it was before ttre Civit War, tf,e "wilderness barrier between the g:';l"

slave commonw.*ftftt of Viiginia and Kentucky'" n'') As late as 1S-"

"f the 10,040,000 acres of Lnd in the state, between nine and :ir:

million were in the original forest.as) The heart and most rugged pi-

of this vast ,riidernes-s lvas the New River region, exle1$ing f ;:'n

Kanawha Falls t" big Bend about thirty mjles west of White S.*rL

nhur Snrinss. CharleE Nordhoff, who t'avelled over the Chesaper*;::

I"J Ofii" firttit. it was u,nder construction in this region, wrote i-u

following account as he made his journey from Kanawha Falls east

over the mountains:

--------------------

44) The tunnel was drilled through "hard red shale crumbling on

exposure e'i (Tunnelling, p' 965) and the cut at east

up, \\,'as -tinillv removed w*tri:n the road bed was widened for double-tracking.

45) Rockingham Register, Feb. 10, 1870

46) Vtt"*tifr g Intelligencer-'- Oct 3,-i871'

47) Tnn Weekly Resister, May 20, 1885.

48) Maury and Fontaine. Resources of West Virginia, p. 143.

_____________________________________

59

When we mounted our horses . . . we bade good-bye to roads and entered the New River country - - a howling wilderness, through which the engineer parties of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad have constructed what it pleases them to call a path, by which path, if you have a sure-footed horse and steady nerves' you may ride at a slow and difficult walk ... If you have ridden into the Yosemite vailey, you will tind here a trail steeper and

nmre difficult than that curious descent, and not two miles but eighty iong . . .

thr New River '.. current is fierce and treacherous; its course is full of

'rnrn'Js, so that navigatio,n is impossibre, and even lumber rafts cannot be

iliuuated on it safely; its banks are steep, and in many parts precipitous, a,nd

nrmr E00 to 1200 feet high. It has for at least fifty miles above the Kanawha

urumolutely no bottom lands or flat shore; and when the engineers were

mmirking surveys for the line of the Chesapeake and Ohio Riilroad, they

ililm to take their measuremen,ts and revels, suspended by ropes, and

m,nn;sported their provisions. and tools on the backs of men from - point to

rilmumr . . . More than two years were consumecl in the survey of the wilct

ilxrumtry between the White Sulphur Springs and the Falls of Kanawha. ae)

To follow the trail of Nordhoff, who in a small party with select

ilrro{mts made an eight-day trip over the line from the ohio River

I@ white sulphur springs, apparently as guests of the railroad for

tu purpose of reporting the work in the Nlw york papers while the

LxEUI'Epany's bonds were on Wall Street, was certainly not inviting to

g *rge army of reporters who could get the officil {(handouts" in

iffinnmond, and who, if they desired, couto observe the work on the

*S il tLe neighborhood of white sulphur springs, particularly that

im l-ervis Tunnel; and Big Bend had been unclei construction about twr:

rrrllrs rvhen Nordhoff made his trip. Obviously the New River section

flRns almost closed t9 th. -public press, echoed in the constanfly

iruffrring lack of authority for the little information published con-

Flxg the construction gangs there. The press of Virginia and west

|],ryniu ya-s -apparently in agreement that Negr,oes kifed in accidents

fu,e hailed fro,m nowhere and had not been christened. The jour-

rnrm[ i" ) on the east .side. of this region carries an account of the progress

*un n"ork at Big Bend "from f private letter,,, and thatst)'on the

'mnm side reports a strike affiong the laborers on the road there from

*Turlors every {uy last wee'kt,. At best the press accounts of

ilding this part of the Chesapeake and ohio are only suggestive,

rqlmril lh.y suggest too much to have any negative beiring-?n the

qtmstiou of a factual basis for the Henry tradition.

Failure of the steel-driver's name to appear in the Federal census

twrt from that locality likewise has no nbgative valu,e in the matter.

k report from Fayette county, in whici the New River section

,tumgely lies, made in June, July, and August of 1920, contains the names of only four employees of the railroad, two white men and

-------------

49) New York Weekly Tribune, Nov. t, 1821. Cf. Anne Royall. Sketches of History, Life, and Manners in the United States, p.40ff.

50) Greenbrier Independent, furne 1. 1872.

51) Kanawha Chronicle, April 13, 1873.

_________________________________________

60

two Negroes; and the report from Forest Hill Township, in which Big Bend lies, contains only the names of three Irish laborers on the road, with those of the engineers and contractors at the tunnel, whereas the Wheeling Intelligencers [52) gives the following for the New River section in May of that year: "The work ea::r-",5*lll:

liorn Cauley, which is the most difficult of all, including tun:'=

cuts and embankments,is being rapidly pushed. There are no\i

mel at work, and the numbeiis to be increased to 6,000 bef::'

close of this month.t'

The chesapeake and ohio Railr'oad should have on file a -r " r""rrri

of the men employed in building the line, but the company has :,--ruu

to favor tfre puntic with such ireport, an_d now claims that th. *'-itt*rr

ior-this peri,od of the road's history ttqy..-b-..1 destroyed by fir. ::llrrrr

ctosing it. possibility of anything oJficial for the steel-driye: dnililrr

for ui adeqiate understandihg oT the conditions under which the

road was built.

In the failure of documentary sources, therefore, the

Iohn Henry and his drilling-contest must rest on testimony,

which of course the reader will take or leave. I regard that brought here as better than "One man against the mountain of negative evidence!" I have not found the one man standing entirely alone and I refuse to recognize the "mountain" at all.

----------------

52) May 17, 1870. Cf. The Greenbrier IndePendent, Jan 22, 1870, for an earlier notice of Negroes at Big Bend.