CHAPTER II

SONGS OF THE AMERICAN SLAVES

Originality of the Afro-American Folksongs — Dr. Wallaschek and his Contention — Extent of Imitations in the Songs — Allusions to Slavery — How the Songs Grew — Are They Entitled to be Called American? — The Negro in American History.

It would never have occurred to me to undertake to prove the existence of genuine folksongs in America, and those the songs which were created by the black slaves of the Southern States, if the fact of such existence had not been denied by at least one writer who has affected the scientific manner, and it had not become the habit of a certain class of writers in this country, while conceding the interesting character of the songs, to refuse them the right to be called American. A foolish pride on the part of one class of Americans of more or less remote English ancestry, and a more easily understood and more pardonable prejudice on the part of former slaveholders and their descendants, might explain this attitude in New England and the South, but why a foreign writer, with whom a personal equation should not have been in any degree operative, should have gone out of his way to pronounce against the originality of the songs of the American negroes, cannot be so readily understood. Yet, in his book, "Primitive Music,"* Dr. Richard Wallaschek says:

There still remains to be mentioned one race which is spread all over America and whose musical powers have attracted the attention of many Europeans — the negro race. It may seem inappropriate to treat of the negroes in this place, but it is of their capabilities under the influence of culture that I wish to make a few remarks. I think I may say that, generally speaking, these negro songs are very much overrated, and that, as a rule, they are mere imitations of European compositions which the negroes have picked up and served up again with slight variations. Moreover, it is a remarkable fact that one author has frequently copied his praise of negro -songs from another, and determined from it the great capabilities of the blacks, when a closer examination would have revealed the fact that they were not musical songs at all, but merely simple poems. This is undoubtedly the case with the oft quoted negro songs of Day and Busch. The latter declares that the lucrative business which negroes made by singing their songs in the streets of American towns determined the whites to imitate them, and with blackened faces to perform their own "compositions" as negro songs. We must be on our guard against the selections of so-called negro songs, which are often offered us as negro compositions.

Miss McKim and Mr. Spaulding were the first to try to make negro songs known, the former of whom, in connection with Allen and Ware, published a large collection which for the most part had been got together by the negroes of Coffin's point and in the neighboring plantations at St. Helena. I cannot think that these and the rest of the songs deserve the praise given by the editors, for they are unmistakably "arranged" — not to say ignorantly borrowed — from the national songs of all nations, from military signals, well-known marches, German student songs, etc., unless it is pure accident which has caused me to light upon traces of so many of them. Miss McKim herself says it is difficult to reproduce in notes their peculiar guttural sounds and rhythmical effects — almost as difficult, in fact as with the songs of birds or the tones of an aeolian harp. "Still, the greater part of negro music is civilized in its character," sometimes influenced by the whites, sometimes directly imitated. After this we may forego the necessity for a thorough examination, although it must be mentioned here, because the songs are so often given without more ado as examples of primitive music. It is, as a matter of fact, no longer primitive, even in its wealth of borrowed melody. Feeling for harmony seems fairly developed.

It was not Miss McKim, but Mr. Allen, who called attention to the "civilized" character of the music of the slaves. In what Miss McKim said about the difficulty of reproducing "the entire character" of the music, as she expresses it, by the conventional symbols of the art, she adduces a proof of the primitive nature of some of its elements. The study of these elements might profitably have occupied Dr. Wallaschek's attention for a space. Had he made more than cursory examination of them he would not have been so sweeping in his characterization of the songs as mere imitations. The authors whom he quotes* wrote before a collection of songs of the American negroes had been made on which a scientific, critical opinion might be based. As for Dr. Wallaschek, his critical attitude toward "Slave Songs" is amply shown by his bracketing it with a publication of Christy minstrel songs which appeared in London; his method is illustrated by his acceptance in his resume of the observations of travellers among savage peoples (an extremely helpful book otherwise) of their terminology as well as their opinions in musical matters. Now, nothing is more notorious than that the overwhelming majority of the travellers who have written about primitive peoples have been destitute of even the most elemental knowledge of practical as well as theoretical music; yet without some knowledge of the art it is impossible even to give an intelligent description of the rudest musical instruments. The phenomenon is not peculiar to African travellers, though the confusion of terms and opinions is greater, perhaps, in books on Africa than anywhere else. Dr. Wallaschek did not permit the fact to embarrass him in the least, nor did he even attempt to set the writers straight so far as properly to classify the instruments which they describe. All kinds of instruments of the stringed kind are jumbled higgledy-piggledy in these descriptions, regardless of whether or not they had fingerboards or belonged to the harp family bamboo instruments are called flutes, even if they are sounded by being struck; wooden gongs are permitted to parade as drums, and the universal "whizzer," or "buzzer" (a bit of fiat wood attached to a string and made to give a whirring sound by being whirled through the air) is treated even by Dr. Wallaschek as if it were an aeolian harp. A common African instrument of rhythm, a stick with one edge notched like a saw, over which another stick is rubbed, which has its counterpart in Louisiana in the jawbone and key, is discussed as if it belonged to the viol family, simply because it is rubbed. He does not challenge even so infantile a statement as that of Captain John Smith when he asserts that the natives of Virginia had "bass, tenor, counter-tenor, alto and soprano rattles." And so on. These things may not influence Dr. Wallaschek's deductions, but they betoken a carelessness of mind which should not exist in a scientific investigator, and justify a challenge of his statement that the songs of the American negroes are predominantly borrowings from

European music.

Besides, the utterance is illogical. Similarities exist between the folksongs of all peoples. Their overlapping is a necessary consequence of the proximity and intermingling of peoples, like modifications of language; and there are some characteristics which all songs except those of the rudest and most primitive kind must have in common. The prevalence of the diatonic scales and the existence of march-rhythms, for instance, make parallels unavoidable. If the use of such scales and rhythms in the folksongs of the American negroes is an evidence of plagiarism or imitation, it is to be feared that the peoples whose music they put under tribute have been equally culpable with them.

Again, if the songs are but copies of "the national songs of all nations, military signals, well-known marches, German student songs, etc., "why did white men blacken their faces and imitate these imitations? Were the facilities of the slaves to hear all these varieties of foreign music better than those of their white imitators? It is plain that Dr. Wallaschek never took the trouble to acquaint himself with the environment of the black slaves in the United States. How much music containing the exotic elements which I have found in some songs, and which I shall presently discuss, ever penetrated to the plantations where these songs grew. It did not need Dr. Wallaschek's confession that he did not think it necessary to make a thorough examination of even the one genuine collection which came under his notice to demonstrate that he did not look analytically at the songs as a professedly scientific man should have done before publishing his wholesale characterization and condemnation. This characterization is of a piece with his statement that musical contests which he mentions of the Nishian women which are "won by the woman who sings loudest and longest" are "still in use in America," which precious piece of intelligence he proves by relating a newspaper story about a pianoforte play ing match in a dime museum in New York in 1892. The truth is that, like many another complacent German savant. Dr. Wallaschek thinks Americans are barbarians. He is

welcome to his opinion, which can harm no one but himself.

That there should be resemblances between some of the songs sung by the American blacks and popular songs of other origin need surprise no one. In the remark about civilized music made by Mr. Allen, which Dr. Wallaschek attributes to Miss McKim, it Is admitted that the music of the negroes is "partly actually imitated from their music," i. e., the music of the whites; but Mr. Allen adds: "In the main it appears to be original in the best sense of the word, and the more we examine the subject, the more genuine it appears to be. In a very few songs, as Nos. ig, 23 and 25, strains of familiar tunes are readily traced; and it may easily.be that others contain strains of less familiar music which the slaves heard their masters sing or play." It would be singular, indeed, if this were not the case, for It is a universal law.

Of the songs singled out by Mr. Allen, No. 19 echoes what Mr. Allen describes as a familiar Methodist hymn, 'Ain't I glad I got out of the Wilderness,' "but he admits that it may be original. I have never seen the song in a collection of Methodist hymns, but I am certain that I used to sing it as a boy to words which were anything but religious. Moreover, the second period of the tune, the only part that is in controversy, has a prototype of great dignity and classic ancestry; it Is the theme of the first Allegro of Bach's sonata In E for violin and clavier. I know of no parallel for No. 23 ("I saw the Beam In my Sister's eye") except in other negro songs. The second period of No. 23 ("Gwine Follow"), as Mr. Allen observes, "Is evidently 'Buffalo,' variously known as 'Charleston' or 'Baltimore Gals.' " But who made the tune for the "gals" of Buffalo, Charleston and Baltimore.'' The melodies which were more direct progenitors of the songs which Christy's Minstrels and other minstrel companies carried all over the land were attributed to the Southern negroes; songs like "Coalblack Rose," "Zip Coon" and "Ole Virglnny Nebber Tire," have always been accepted as the creations of the blacks, though I do not know whether or not they really are. Concerning them I am skeptical, to say the least, if only for the reason that we have no evidence on the subject.

So-called negro songs a.re more than a century old in the music-rooms of America'; A song descriptive of the battle of Plattsburg was sung in a drama to words supposedly in negro dialect, as long ago as 1815. "Jump Jim Crow" was caught by Thomas D. ("Daddy") Rice from the singing and dancing of an old, deformed and decrepit negro slave in Louisville eighty-five years ago (if the best evidence obtainable on the subject is to be believed), and this was the starting-point of negro minstrelsy of the Christy type. "Dandy Jim of Caroline" may also have had a negro origin; I do not know, and the question is inconsequential here for the reason that the Afro-American folksongs which I am trying to study owe absolutely nothing to the songs which the stage impersonators of the negro slave made popular in the United States and England. They belong to an entirely different order of creations. For one thing, they are predominantly religious songs; it is a singular fact that very few secular songs — -those which are referred to as "reel tunes," "fiddle songs," "corn songs" and "devil songs," for which the slaves generally expressed a deep abhorrence, though many of them, no doubt, were used to stimulate them while songs" and other "speritchils" (spirituals — "ballets" they were called at a later day) have been kept alive by the hundreds. The explanation of the phenomenon is psychological.

There are a few other resemblances which may be looked into. "Who is on the Lord's side?"' may have suggested the notion of "military calls" to Dr. Wallaschek. "In Bright Mansions Above" contains a phrase which may have been inspired by "The Wearing of the Green." A palpable likeness to "Camptown Races" exists in "Lord, Remember Me."* Stephen C. Foster wrote "Camptown Races" in 1850; the book called "Slave Songs of the United States" was published in 1867, but the songs were collected several years before. I have no desire to rob Foster of the credit of having written the melody of his song; he would have felt justified had he taken it from the lips of a slave, but it is more than likely that he invented it and that it was borrowed in part for a hymn by the negroes. The "spirituals" are much sophisticated with worldly sentiment and phrase.

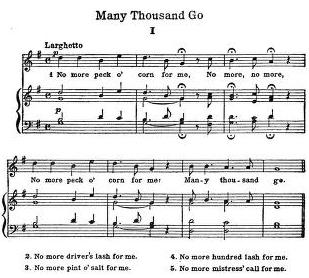

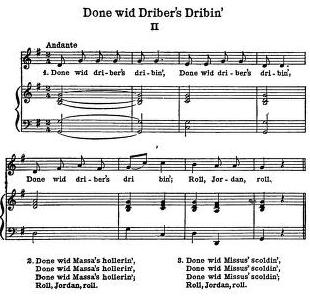

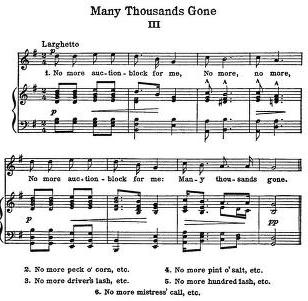

There are surprisingly few references to the servitude of the blacks in their folksongs which can be traced to ante-bellum days. The text of "Mother, is Massa Gwine to sell us To-morrow?" would seem to be one of these; but it is not in the earliest collection and may be of later date in spite of its sentiment. I present three interesting examples which celebrate the deliverance from slavery, of which two, "Many Thousands Gone"' and "Many Thousand Go"^ are obviously musical variants of the same song (see pages 18, 19, 20).

Colonel Higginson, who collected the second, says of it in his "Atlantic Monthly" essay: "They had another song to which the Rebellion had actually given rise. This was composed by nobody knew whom — though it was the most recent, doubtless, of all these 'spirituals' — and had been sung in secret to avoid detection. It is certainly plaintive enough. The peck of corn and pint of salt were slavery's rations." The editors of "Slave Songs" add: "Lieutenant-Colonel Trowbridge learned that it was first sung when Beauregard took the slaves to the islands to build the fortifications at Hilton Head and Bay Point." The third song, "Done wid Briber's Dribin'," was first printed in Mr. H. G. Spaulding's essay "Under the Palmetto" in the "Continental Monthly" for August, 1863. The song "Oh, Freedom over Me," which Dr. Burghardt du Bois quotes in his "The Souls of Black Folk" as an expression of longing for deliverance from slavery encouraged by fugitive slaves and the agitation of free negro leaders before the War of the Rebellion, challenges no interest for its musical contents, since it is a compound of two white men's tunes — "Lily Dale," a sentimental ditty, and "The Battle-Cry of Freedom," a patriotic song composed by George F. Root, in Chicago, and inspired by President Lincoln's second call for volunteers in the summer of 1861. There was time for the negro song to have grown up between 1861 and the emancipation of the slaves, but it is not likely that slaves anywhere in the United States outside of the lines of the Federal armies would have dared to sing

O Freedom, O Freedom,

O Freedom over me!

Before I'll be a slave.

I'll be buried in my grave,

And go home to my Lord,

And be free!

before 1863. Besides, the song did not appear in print, I believe, till it was published in "Religious Folk Songs of the Negro, as Sung on the Plantations," an edition of "Cabin and Plantation Songs as Sung by the Hampton Students," published in 1909. The early editions of the book knew nothing of the song. Colonel Higginson quotes a song with a burden of "We'll soon be free," for singing which negroes had befen put in jail at the outbreak of the Rebellion in Georgetown, S. C. In spite of the obviously apparent sentiment, Colonel Higginson says It had no reference to slavery, though he thinks it may have been sung "with redoubled emphasis during the new events." It was, in fact, a song of hoped-for deliverance from the sufferings of this world and of anticipation of the joys of Paradise, where the faithful were to "walk de miry road" and "de golden streets," on which pathways ^'pleasure never dies." No doubt there was to the singers a hidden allegorical significance in the numerous allusions to the deliverance of the Israelites from Egyptian bondage contained in the songs, and some of this significance may have crept into the songs before the day of freedom began to dawn. A line, "The Lord will call us home," in the song just referred to, Colonel Higginson says "was evidently thought to be a symbolical verse; for, as a little drummer-boy explained to me, showing all his white teeth as he sat in the moonlight by the door of my tent, 'Dey tink de Lord mean for say de Yankees.' "

THREE EMANCIPATION SONGS

I. Words and Melody from "Slave Songs of the United States";— II. From "The Continental Monthly" of August, 1863, reprinted in "Slave Songs";— III. From "The Story of the Jubilee Singers." The arrangements are by H. T, Burleigh. [Note that I and III are versions of the same song- Matteson 2011]

I. Many Thousand Go

1. No more peck o' com for me,

No more, no more.

No more peck o' corn for me;

Many thousand go.

2. No more driver's lash for me,

3. No more pint o' salt for me.

4. No more hundred lash far me,

5. No more mistress' call for me.

II. Done wid Briber's Dribin'

1. Done wid driber's dribin',

Done wid driber's dribin,

Done wid driber's dribin;

Roll, Jordan, roll.

2. Done wid Massa's hollerin'.

Done wid Massa's hollerin'.

Done wid Uassa's hollerin';

Roll, Jordan, roll.

3. Done wid Missus' scoldin',

Done wid Missus' scoldin'.

Done wid Missus' scoldin';

Roll, Jordan, roll.

III. Many Thousands Gone

1. No more auction-block for me;

No more, no more.

No more auction-block for me;

Many thousands gone.

2. No more peck o' corn, etc

3. No more driver's lash, etc.

4. No more pint o'salt, etc.

5. No more hundred lash, etc.

6. No more mistress' call, etc.

If the songs which came from the plantations of the South are to conform to the scientific definition of folksongs as I laid it down in the preceding chapter, they must be "born, not made;" they must be spontaneous utterances of the people who originally sang them; they must also be the fruit of the creative capacity of a whole and ingenuous people, not of individual artists, and give voice to the joys, sorrows and aspirations of that people. They must betray the influences of the environment in which they sprang up, and may preserve relics of the likes and aptitudes of their creators when in the earlier environment from which they emerged. The best of them must be felt by the singers themselves to be emotional utterances.

The only considerable body of song which has come into existence in the territory now compassed by the United States, I might even say in North America, excepting the primitive songs of the Indians (which present an entirely different aspect), are the songs of the former black slaves. In Canada the songs of the people, or that portion of the 'people that can be said still to sing from impulse, are predominantly French, not only in language but in subject. They were for the greater part transferred to this continent with the bodily integrity which they now possess. Only a small portion show an admixture of Indian elements; but the songs of the black slaves of the South are original and native products. They contain idioms which were transplanted hither from Africa, but as songs they are the product of American institutions; of the social, political and geographical environment within which their creators were placed in America; of the influences to which they were subjected in America; of the joys, sorrows and experiences which fell to their lot in America.

Nowhere save on the plantations of the South could the emotional life which is essential to the development of true folksong be developed; nowhere else was there the necessary meeting of the spiritual cause and the simple agent and vehicle. The white inhabitants of the continent have never been in the state of cultural ingenuousness which prompts spontaneous emotional utterance in music.

Civilization atrophies the faculty which creates this phenomenon as it does the creation of myth and legend. Sometimes the faculty is galvanized into life by vast calamities or crises which shake all the fibres of social and national existence; and then we see its fruits in the compositions of popular musicians. Thus the War of the Rebellion produced songs markedly imbued with the spirit of folksong, like "The Battle-Cry of Freedom," "Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys are Marching," and "Marching Through Georgia." But it is a singular fact that the patriotic songs of the American people during the War of the Revolution and the War of 1812 were literary and musical parodies of English songs. We took the music of "Yankee Doodle" and "The Star-Spangled Banner" from the lips of the enemy.

It did not lie in the nature of the mill life of New England or the segregated agricultural life of the Western pioneers to inspire folksongs; those occupations lacked the romantic and emotional elements which existed in the slave life of the plantations in the South and which invited celebration in song — grave and gay. Nor were the people of the North possessed of the ingenuous, native musical capacity of the Southern blacks. '

It is in the nature of things that the origin of individual folksongs should as a rule remain unknown; but we have evidence to show how some of them grew, and from it we deduce the general rule as it has been laid down. Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, in his delightful essay "Negro Spirituals," published in "The Atlantic Monthly" for June, 1867, tells an illuminative anecdote. Speaking of "No More Peck of Corn for Me," he says:

"Even of this last composition, however, we have only the approximate date, and know nothing of the mode of composition. Allen Ramsey says of the Scotch songs that, no matter who made them, they were soon attributed to the minister of the parish whence they sprang. And I always wondered, about these, whether they had always a conscious and definite origin in some leading mind or whether they grew by gradual accretion in an almost unconscious way. On this point I could get no information, though I asked many questions, until at last one day when I was being rowed across from Beaufort to Ladies' Island, I found myself, with delight, on the actual trail of a song. One of the oarsmen, a brisk young fellow, not a soldier, on being asked for his theory of the matter, dropped out a coy confession. "Some good sperituals," he said, "are start jest out o' curiosity. I bin a-raise a sing myself once."

My dream was fulfilled, and I had traced out not the poem alone, but the poet. I implored him to proceed.

"Once we boys went for tote some rice, and de nigger driver, he keep a-callin' on us: and I say, 'O, de ole nigger driver!" Den anudder said, Fust t'ing my mammy tole me was not'in' so bad as a nigger driver.' Den I made a sing, just puttin* a word and den anudder word."

Then he began singing and the men, after listening a moment, joined in the chorus as if it were an old acquaintance, though they evidently had never heard it before. I saw how easily a new "sing" took root among them.

"O, de ole nigger driver!

O, gwine away!

Fust t'ing my mammy tell me.

O, gwine away!

Tell me 'bout de nigger driver,

O, gwine away!

Nigger driver second devil,

O, gwine away!

Best t'ing for do he driver,

O, gwine away!

Knock he down and spoil he labor —

O, gwine away!

A similar story, which also throws light on the emancipation songs which I have printed, was told by J. Miller McKim in an address delivered in Philadelphia on July 9, 1862:

I asked one of these blacks, one of the most intelligent of them, where they got these songs.

"Dey make 'em, sah."

"How do they make them?"

After a pause, evidently casting about for an explanation, he said:

"I'll tell you; it's dis way: My master call me up an' order me a short peck of corn and a hundred lash. My friends see it and is sorry for me. When dey cpme to de praise meeting dat night dey sing about it. Some's very good singers and know how; and dey work it in, work it in, you know, till dey get it right; and dat's de way."

"In ancient Rome sick slaves were exposed on the island of- Aesculapius, in the Tiber; by a decree of Claudius slaves so exposed could not be reclaimed by their master." — (Encyclopaedia Britannica, art. "Slavery.")

An incident which gave rise in Jamaica to a folksong, which is a remarkably fine example of dramatic directness and forcefulness, but of which, most unfortunately, the music has not been preserved, recalls this ancient regulation. Here is the song:

"Take him to the gully! Take him to the gully.

But bringee back the frock and the board."

"O massa, raassa! Me no deadee yet!"

"Take him to the gully! Take him to the gully;

Carry him along!"

How this song came into existence is thus related in A Journal of a Residence Among the Negroes in the West Indies," by Matthew Gregory Lewis. The song alludes to a transaction which took place about fifty years ago on an estate called Spring Garden, the owner of which is quoted as the cruelest proprietor that ever disgraced Jamaica. It was his constant practice, whenever a sick negro was pronounced incurable, to order the poor wretch to be carried to a solitary vale upon his estate, called the Gully, where he was thrown down and abandoned to his fate — which fate was generally to be half-devoured by the John crows before death had put an end to his sufferings. By this proceeding the avaricious owner avoided the expense of maintaining the slave during his last illness; and in order that he might be as little a loser as possible h6 always enjoined the negro bearers of the dying man to strip him naked before leaving the Gully, and not to forget to bring back his frock and the board on which he had been carried down.

One poor creature, while in the act of being removed, screamed out most piteously that he was not dead yet, and implored not to be left to perish in the Gully in a manner so horrible. His cries had no effect upon the master, but operated so forcibly on the less marble hearts of his fellow slaves that in the night some of them removed him back to the negro village privately and nursed him there with so much care that he recovered and left the estate unquestioned and undiscovered. Unluckily, one day the master was passing through Kingston, whtn, on turning the corner of a street suddenly, he found himself face to face with the negro whom he had supposed long ago to have been picked to the bones in the Gully. He immediately seized him, claimed him as his slave and ordered his attendants to convey him to his house; but the fellow's cry attracted, a crowd around them before he could be dragged away. He related his melancholy story and the singular manner in which he had recovered his life, and liberty, and the public indignation was so forcibly excited by the shocking tale that Mr. B was glad to save himself from being torn to pieces by a precipitate retreat from Kingston and never ventured to advance his claim to the negro A second time.

But the Story lived in the song which the narrator heard half, a century later. Imagine the dramatic pathos of the words paired with the pa^ljos of the tune which welled up with them when the singers repeated the harsh utterances of the master and the pleadings of the wretched slave! It is out of experiences like these, that folksongs are made.

There were, it is true, few cases of such monstrous cruelty in any of the sections in which slavery flourished in America, though it fell to my lot fifteen years after slavery had been abolished to report the testimony in a law case of an old black woman who was seeking to recover damages from a former Sheriff of Kenton County, Ky., for having abducted her, when a free woman living in Cincinnati, and selling her into slavery. A slave she remained until freed by President Lincoln's proclamation, and in measure of damages she told on the witness stand of seeing a young black woman on a plantation in Mississippi stripped naked, tied by the feet and hands flat upon the ground and so inhumanly flogged that she died in a few- hours. That story also might well have been perpetuated in a folksong. There was sunshine as well as' gloom in the life of the black slaves in the Southern colonies and States, and so we have songs which are gay as well, as grave; but as a rule the finest songs are the fruits of suffering undergone and the hope of the deliverance from bondage which was to come with translation to heaven after death.

The oldest of them are the most beautiful, and many of the most striking have never yet been collected, partly because they contained elements, melodic as well as rhythmical, which baffled the ingenuity of the early collectors. Unfortunately, trained musicians have never entered upon the field, and it is to be feared that it is now too late. The peculiarities which the collaborators on. "Slave Songs of the United States" recognized, but could not imprison on the written page, were elements which would have been of especial interest to the student of art.

Is it not the merest quibble to say that these songs are not American? They were created in America under American influences and by people who are Americans in the same sense that any other element of our population is American — every element except the aboriginal. But is there an aboriginal element? Are the red men autocthones? Science seems to have answered that they are not. Then they, too, are American only because they have come to live in America. They may have come from Asia. The majority of other Americans came from Europe. Is it only an African who can sojourn here without becoming an American and producing American things? Is it a matter of length of stay in the country? Scarcely that; or some negroes would have at least as good a claim on the title as the descendants of the Puritans and Pilgrims. Negroes figure in the accounts of his voyages to America made by Columbus. Their presence in the West Indies was noticed as early as 1501. Balboa was assisted by negroes in building the first ships sent into the Pacific Ocean from American shores. A year before the English colonists landed on Plymouth Rock negroes were sold into servitude in Virginia.* When the first census of the United States was taken in 1790, there were 757,208 negroes in the country. There are now 10,000,000. These people all speak the language of America. They are native born. Their songs, a matter of real moment in the controversy, are sung in the language of America (albeit in a corrupt dialect), and as much entitled to be called American songs as would be the songs, were there any such, created here by any other element of our population. They may not give voice to the feelings of the entire population of the country, but for a song which shall do that we shall Jiave to wait until the amalgamation of the inhabitants of th& United States is complete. Will such a time ever come? Perhaps so; but it will be after the people of the world -cease swarming as they have swarmed from the birth of history till now. There was a travelled road from Mesopotamia to the Pillars of Hercules in the time of Abraham. The women of Myksene wore beads of amber brought from the German Ocean, when

"Ilion, like a mist, rose into towers."

The folksongs of Suabia, Bavaria, the Rhineland, Franconia- — of all the German countries, principalities and provinces — are German folksongs; the songs of the German apprentices, soldiers, huntsmen, clerks, journeymen — giving voice to the experiences and feelings of each group — are all German folksongs. Why are not the songs of the American negroes American folksongs.'' Can any one say? It is deplorable that so pessimistic a note should sound through the writings of any popular champion as sounds through the most eloquent English book ever written by any one of African blood; but no one shall read Burghardt DuBois's "The Souls of Black Folk'* without being moved by the pathos of his painful cry:

"Your country? How came it yours? Before the Pilgrims landed we were here. Here we have brought our three gifts and mingled them with yours — a gift of story and song, soft, stirring melody in an ill harmonized^ and unmelodious land; the gift of sweat and brawn to beat back the wilderness, conquer the soil and lay the foundations of this vast economic empire two hundred years earlier than your weak hands could have done it: the third- a gift of the Spirit. Around us the history of the land has centered for thrice a hundred years; out of the nation's heart we have called all that was best to throttle and subdue all that was worst; fire and blood, prayer and sacrifice, have billowed over this people, and they have found peace only in the altars- of the God of Right. Nor has our gift of the Spirit been merely passive Actively we have woven ourselves with the very warp and woof of this nation — we fought their battles, shared their sorrows, mingled our blood with theirs, and generation after generation have pleade.d with a headstrong, careless people to despise not Justice, Mercy and Truth, lest the nation be smitten- with a curse. Our song, our toil, our cheer and warning have been given to this nation in blood brotherhood. Are not these gifts worth giving.' Is not this work and striving? Would America have been America without her negro people?

Even so is the hope that sang in the songs of my fathers well sung. If somewhere in this swirl and chaos of things there dwells Eternal Good, pitiful yet masterful, then anon in His good time America shall rend the veil and the prisoned shall go free — free, free as the sunshine trickling down the morning into these high windows of mine; free as yonder fresh voices welling up to me- from the caverns of brick and mortar below — swelling with song, instinct with life, tremulous treble and darkening bass.

Greatly as it pains me, I should be sorry if one should ask me to strike that passage out of "American" prose writing.

Footnotes:

* An Inquiry into the Origin and Development of Music, Songs, Instruments, Dances and Pantomines of Savage Races" (London, 1893).

* Charles William Day, who published a work entitled "Five Years Residence m the West Indies," in 1852, and Moritz Busch, who in 18S4 pubhshed his Wanderungen zwischen Hudson und Mississippi."

1 London, 184S.

["Slave Songs," No. 75.]

[ 2 No. 78 of the Fisk Jubilee Collection

3 No. 7 in "Slave Songs"

» Fisk Jubilee Collection, No. 23

2 "Slave Songs," No. 64