Afro-American Folksongs

A STUDY IN RACIAL AND NATIONAL MUSIC

BY

Henry Edward Krehbiel

[This book has a small collection of Spirituals from the US (with music), mostly collected in Louisville, not published in other books. The information is presented in an academic detailed manner not suited for the casual reader. Krehbiel also covers the songs of the black Creoles and touches on music of the Bahamas and Africa. Many of the spirituals found in the Bahamas in the late 1800s have corresponding version in the US.

This page has Title Page, Preface, Contents, Appendices and the Index. There are ten musical transcriptions in the Appendix below.]

Krehbiel is author of "Studies in the Wagnerian Drama," "How to Listen to Music," "Music and Manners in the Classical Period," "Chapters of Opera," "A Book OF Operas," "The Pianoforte and its Music," etc., etc.

G. SCHIRMER

NEW YORK AND LONDON

Copyright, 1914, by

G. SCHIRMER

TO MY FRIEND

HORATIO W. PARKER, Mus. Doc.

Professor of Music at Yale University

PREFACE

This book was written with the purpose of bringing a species of folksong into the field of scientific observation and presenting it as fit material for artistic treatment. It is a continuation of a branch of musical study for which the foundation was laid more than a decade ago in a series of essays with bibliographical addenda printed in the New York "Tribune," of which journal the author has been the musical reviewer for more than thirty years. The general subject of those articles was folksongs and their relation to national schools of composition. It had come to the writer's knowledge that the articles had been clipped from the newspaper, placed in envelopes and indexed in several public libraries, and many requests came to him from librarians and students that they be republished in book-form. This advice could not be acted upon because the articles were mere outlines, gi-ound-plans, suggestions and guides to the larger work or works which the author hoped would the be the result of his instigation.

Folksong literature has grown considerably since then, especially in Europe, but the subject of paramount interest to the people of the United States has practically been ignored. The songs created by the negroes while they were slaves on the plantations of the South have cried out in vain for scientific study, though "ragtime" tunes, which are their debased offspring, have seized upon the fancy of the civilized world. This popularity may be deplorable, but it serves at least to prove that a marvellous potency lies in the characteristic rhythmical element of the slave songs. Would not a wider and truer knowledge of their other characteristics as well lead to the creation of a better art than that which tickles the ears and stimulates the feet of the pleasure-seekers of London, Paris, Berlin and Vienna even more than it does those of New York?

The charm of the Afro-American songs has been widely recognized, but no musical savant has yet come to analyze them. Their two most obvious elements only have been copied by composers and dance-makers, who have wished to imitate them. These elements are the rhythmical propulsion which comes from the initial syncopation common to the bulk of them (the "snap" or "catch" which in an exaggerated form lies at the basis of "ragtime") and the frequent use of the five-tone or pentatonic scale. But there is much more that is characteristic in this body of melody, and this "more" has been neglected because it has not been uncovered to the artistic world. There has been no study of it outside of the author's introduction to the subject printed years ago and a few comments, called forth by transient phenomena, in the "Tribune" newspaper in the course of the last generation. This does not mean that the world has kept silent on the subject. On the contrary, there has been anything but a dearth of newspaper and platform talk about songs which the negroes sang in America when they were slaves, but most of it has revolved around the questions whether or not the songs were original creations of these native blacks, whether or not they were entitled to be called American and whether or not they were worthy of consideration as foundation elements for a school of American composition.

The greater part of what has been written was the result of an agitation which followed Dr. Antonin Dvorak's efforts to direct the attention of American composers to the beauty and efHciency of the material which these melodies contained for treatment in the higher artistic forms. Dr. Dvorak's method was eminently practical; he composed a symphony, string quartet and string quintet in which he utilized characteristic elements which he had discovered in the songs of the negroes which had come to his notice while he was a resident of New York. To the symphony he gave a title — "From the New World" — which measurably disclosed his purpose; concerning the source of his inspiration for the chamber compositions he said nothing, leaving it to be discovered, as it easily was, from the spirit, or feeling, of the music and the character of its melodic and rhythmic idioms. The eminent composer's'aims, as well as his deed, were widely misunderstood at the time, and, for that matter, still are. They called out a clamor from one class of critics which disclosed nothing so much as their want of intelligent discrimination unless it was their ungenerous and illiberal attitude toward a body of American citizens to whom at the least must be credited the creation of a species of song in which an undeniably great composer had recognized artistic potentialities thitherto neglected, if not unsuspected, in the land of its origin. While the critics quarrelled, however, a group of American musicians acted on Dr. Dvorak's suggestion, and music in the serious, artistic forms, racy of the soil from which the slave songs had sprung, was produced by George W. Chadwick, Henry Schoenberg, Edward R. Kroeger and others.

It was thus that the question of a possible folksong basis for a school of composition which the world would recognize as distinctive, even national, was brought upon the carpet. With that question I am not concerned now. My immediate concern is to outline the course and method to be pursued in the investigations which I have undertaken. Primarily, the study will be directed to the music of the songs and an attempt be made by comparative analysis to discover the distinctive idioms of that music, trace their origins and discuss their correspondences with characteristic elements of other folk-melodies, and also their differences.

The burden is to be laid upon the music. The poetry of the songs has been discussed amply and well, never so amply or so well as when they were first brought to the attention of the world by a group of enthusiastic laborers in the cause of the freedmen during the War of the Rebellion. Though foreign travellers had written enthusiastically about the singing of the slaves on the Southern plantations long before, and though the so-called negro minstrels had provided an admired form of entertainment based on the songs and dances of the blacks which won unexampled popularity far beyond the confines of the United States, the descriptions were vague and general, the sophistication so great, that it may be said that really nothing was done to make the specific beauties of the unique songs of the plantations known until Miss McKim wrote a letter about them to Dwight's "Journal of Music," which was printed under the date of November 8, 1862.

In August, 1863, H. G. Spaulding contributed some songs to "The Continental Monthly," together with an interesting account of how they were sung and the influence which they exerted upon the singers. In "The Atlantic Monthly" for June, 1867, Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson printed the texts of a large number of songs and accompanied them with so sympathetic and yet keen an analysis of their psychology and structure that he left practically nothing for his successors to say on the subject. Booker T. Washington and W. E. Burghardt DuBois have only been able to echo him in strains of higher rhapsody. Much use was made of these articles by William Francis Allen in the preface of the first collection of the songs, entitled "Slave Songs of the United States,/' published by A. Simpson & Co. in New York in 1867. The observations of these writers and a few others make up practically the entire sum of what it is essential to know about the social, literary and psychological side of the folksongs of the American negroes. None of these early collectors had more than a smattering of musical knowledge, and none of them attempted to subject the melodies of the songs to analytical study.

Outside of the cursory and fragmentary notices of "The Tribune's" music reviewer called out by a few performances of the songs and the appearance of the collections which followed a popularization of the songs by the singing of the Jubilee Singers of the Fisk University and other choirs from the schools established for the higher education of the emancipated blacks, nothing of even a quasi-scientific character touching the melodies appeared during the last generation until M. Julien Tiersot, the distinguished librarian of the Paris Conservatory, published, a monograph* (first in the Journal of the International Music Society, afterward separately) giving the results of his investigations into the folk-music of Canada and the United States made during a visit to America in the winter and spring of 1905- 1906.

[* "La Musique chez les Peupks indigenes de I'Amerique du Nord — Etats- Unis et Canada." Paris, Librairie Fischbacher; Leipsic and New York, Breitkopf & Hartel. ]

A few months ago a book entitled "Musik, Tanz und Dichtung bei den Kreolen Amerikas," by Albert Friedenthal, was published in Berlin. M.Tiersot concerned himself chiefly with the Indians, though he made some keen observations on the music of the black Creoles of Louisiana, and glanced also at the slave songs, for which he formed a sincere admiration; the German folklorist treated of negro music only as he found it influencing the dances of the people of Mexico, Central America, South America and the West Indies.

The writer of this book, therefore, had to do the work of a pioneer, and as such will be satisfied if he shall succeed in making a clearing in which successors abler than he shall work hereafter.

The scope of my inquiry and the method which I have pursued may be set forth as follows:

1. First of all it shall be detennined what are folksongs, and whether or not the songs in question conform to a scientific definition in respect of their origin, their melodic and rhythmical characteristics and their psychology.

2. The question, "Are they American?" shall be answered.

3. Their intervallic, rhythmical and structural elements will be inquired into and an effort be made to show that, while their combination into songs took place in this country, the essential elements came from Africa; in other words, that, while some of the material is foreign, the product is native; and, if native, then American.

4. An effort will be made to disprove the theory which has been frequently advanced that the songs are not original creations of the slaves, but only the fruit of the negro's innate faculty for imitation. It will be shown that some of the melodies have peculiarities of scale and structure which could not possibly have been copied from the music which the blacks were privileged to hear on the plantations or anywhere else during the period of slavery. Correspondence will be disclosed, however, between these peculiarities and elements observed by travellers in African countries.

5. This will necessitate an excursion into the field of primitive African music and also into the philosophy underlying the conservation of savage music. Does it follow that, because the American negroes have forgotten the language of their savage ancestors, they have also forgotten all of their music? May relics of that music not remain in a subconscious memory?

6. The influences of the music of the dominant peoples with whom the slaves were brought into contact upon the rude art of the latter will have to be looked into and also the reciprocal effect upon each other; and thus the character and nature of the hybrid art found in the Creole songs and dances of Louisiana will be disclosed.

To make the exposition and arrangement plain, I shall illustrate them by musical examples, African music will be brought forward to show the sources of idioms which have come over into the folksongs created by negroes in America; and the effect of these idioms will be demonstrated by specimens of song collected in the former slave States, the Bahamas and Martinique. Though for scientific reasons I should have preferred to present the melodies of these songs without embellishment of any sort, I have yielded to a desire to make their peculiar beauty and usefulness known to a wide circle of amateurs, and presented them in arrangements suitable for performance under artistic conditions.

For these arrangements I am deeply beholden to Henry T. Burleigh, Arthur Mees, Henry Holden Huss and John A. Van Broekhoven. An obligation of gratitude is also acknowledged to Mr. Ogden Mills Reid, Editor of "The New York Tribune," for his consent to the reprinting of the essays ; to Mr. George W. Cable and The Century Company for permission to use some of the material in two of the former's essays on Creole Songs and Dances published in 1886 in "The Century Magazine;" and to Professor Charles L. Edwards, the American Folk-Lore Society, Miss Emily Hallowell and Harper & Brothers for like privileges.

H. E. Krehbiel.

Blue Hill, Me.

Summer of 1913.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

CONTENTS PAGE

Chapter I. Folksongs in General; page 1

The Characteristics of Folksong-- Folksongs Defined-- Creative Influences — Folksong and Suffering --Modes, Rhythms and Scales. — Russian and Finnish Music — Persistency of Type. — Music and Racial Ties — Britons and Bretons.

Chapter II. Songs of the American Slaves 11

Originality of the Afro-American Folksongs — Dr. Wallaschek and His Contentiom. — Extent of the_ Imitation in the Songs. — Allusions to Slavery.— Hovre Siwf — Are They Entitled to be Called American? — The Negro in American History.

Chapter III. Religious Character of the Songs 26

The Paucity of Secular Songs among the Slaves. — Campmeetings, "Spirituals" and "Shouts." — Work- Songs of the Fields and Rivers. — Lafcadio Hearn and Negro Music. — African Relics and Voodoo Ceremonies.

Chapter IV. Modal Characteristics of the Songs 42

An Analysis of Half a Thousand Negro Songs. — Division as to Modes. — Overwhelming Prevalence of Major. — Psychology of the Phenomenon. — Music as a Stimulus to Work. — Songs of the Fieldhands and Rowers.

Chapter V. Music Among the Africans 56

The Many and Varied Kinds of African Slaves. — Not All Negroes. — Their Aptitude and Love for Music. — Knowledge and Use of Harmony. — Dahomans at Chicago. — Rhythm and Drumming. — ^African Instruments.

Chapter VI. Variations from the Major Scale 70

Peculiarities of Negro Singing. — Vagueness of Pitch in Certain Intervals. — Fractional Tones in Primitive Music. — The Pentatonic Scale. — The Flat Seventh. — Harmonization of Negro Melodies.

Chapter VII. Minor Variations and Characteristic Rhythms 83

Vagaries in the Minor Scale. — The Sharp Sixth. — Orientalism.— The "Scotch" Snap.— A Note on the Tango Dance. — Even and Uneven Measures. — Adjusting Words and Music.

Chapter VIII. Structural Features of the Poems. Funeral Music 100

Improvization. — Solo and Choral Refrain. — Strange Funeral Customs. — Their Savage Prototypes. — Messages to the Dead. — Graveyard Songs of the American Slaves.

Chapter IX. Dances of the American Negroes 112

Creole Music. — The Effect of Spanish Influences. — Obscenity of Native African Dances. — Relics in the Antilles. — The Habanera. — Dance-Tunes from Martinique.

Chapter X. Songs of the Black Creoles 127

The Language of the Afro-American Folksongs. — Phonetic Changes in English. — Grammar of the Creole Patois. — Making French Compact and Musical. — Dr. Mercier's Pamphlet. — Creole Love-Songs.

Chapter XI. Satirical Songs of the Creoles 140

A Classification of Slave Songs. — The Use of Music in Satire. — African Minstrels. — The Carnival in Martinique. — West Indian Pillards. — Old Boscoyo's Song in New Orleans. — Conclusion. — An American School of Composition.

Appendix of Ten Characteristic Songs 157

Index 171

-----------------------------------------------------

Appendix of Ten Characteristic Songs

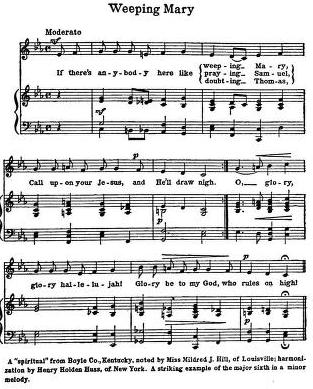

1) Weeping Mary

A "spiritual" from Boyle Co., Kentacky, noted by Miss Mildred J. Hill, of Louisville; harmonized by Henry Holden Boss, of New York. A striking example of the major sixth in a minor melody.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

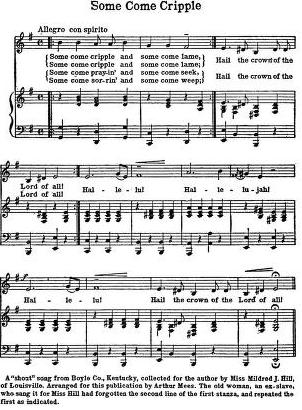

2) Some Come Cripple

1. Some come cripple and some come lame,

Some come cripple euid some come lame;

Hail the crown of the Lord of all.

Some come pray-in' and some come seek,

Some come sor-rin' and some come weep

Hail the crown of the Lord of all.

Hallelu! Hallelujah!

Hallelu!

Hail the crown of the Lord of all.

A"short'' song from Boyle Co., Kentucky, collected for the author by Miss Hildred J. Bill, of Louisviille. Arranged for this pablication by Arthur Hees. The old woman, an ex-slave, whosang it for Hiss Hill had forgotten the second line of the first-stanza, and repeated the first as indicated.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

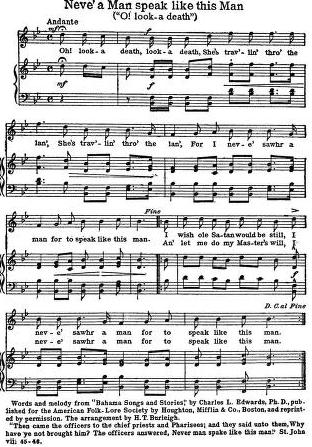

3) Neve' a Man speak like this Man ("O! look- a death")

Oh! look, a death, look- a death,

She's trav'lin' thro' the lan',

She's trav'lin' thro' the lan',

For I neve' sawhr a man for to speak like this man.

I wish ole Satan would be still,

I neve' sawhr a man for to speak like this man.

An let me do my Mas-ter-s will,

I neve' sawhr a man for to speak like this man.

Words and melody from "Bahama Songs and Stories',' by Charles L. Edwards, Ph. D., published for the American Folk- Lore Society by Houghton, Mifflin & Co., Boston, and reprinted by permission. The arrangement by H.T. Burleigh.

"Then came the officers to the chief priests and Pharisees; and they said onto them, Why have ye not brought him? The officers answered, Never man spake like this man!' St. John vii: 45- 46.

------------------------------------------------------

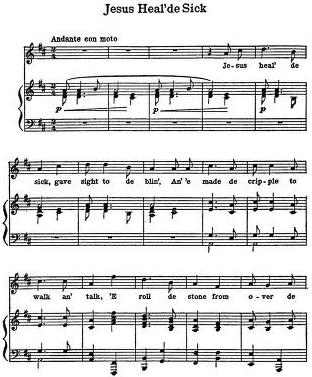

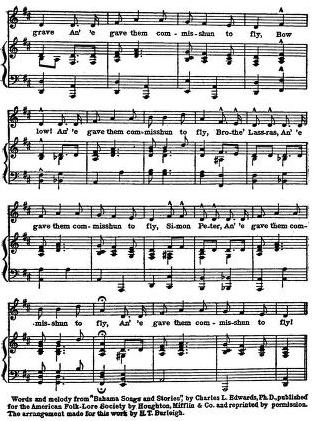

4) Jesus Heal de Sick

Jesus heal' de sick, gare sight to de blin',

An' 'e made de cripple to walk and talk

'E roll de stone over de grave,

An' 'e gave them commisshon to fly, bow low

An 'e gave them commisshun to fly, Brothe' Lassras,

An' 'e gave them commisshon to fly, Simon Peter,

An' 'e gave them commisshon to fly!

An' 'e gave them commisshon to fly!

Words and melody From 'Bahama Songs and Stories" by Charles L. Edwards, Ph.D, published for the American Folk-Lore Society by Houghton, Miffin & Co. and reprinted by permission. 'The arrangement made for this work by B.T. Burleigh.

----------------------------------------------------------

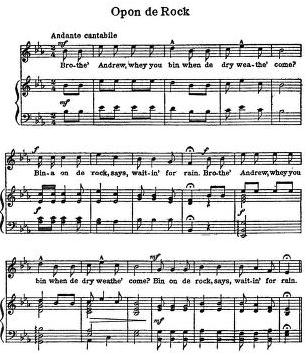

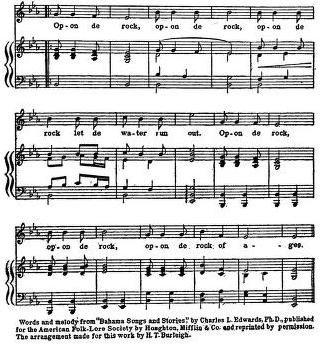

5) Opon de Rock

Brothe' Andrew, whey you bin when de dry weathe' come?

Bin-a on de rock, Says, waitin' for rain.

Brothe' Andrew, whey you bin when de dry weathe' come?

Bin-a on de rock, Says, waitin' for rain.

Words and melody From 'Bahama Songs and Stories" by Charles L. Edwards, Ph.D, published for the American Folk-Lore Society by Houghton, Miffin & Co. and reprinted by permission. 'The arrangement made for this work by B.T. Burleigh.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Nobody Knows the Trouble I See

No4iod-7 knows the trouble I see, Lord, Nobod-y knows the

trou-ble I see; No - bod - 7 knows the tf oit-ble I see. Lord,

No-bod -y knows like Je • sus. Brothers, will you pray for me,

pray for me, And hslp me to drive old Sa - tan a - way?

Arranged for men's voices by Arthur Mees for the Mendelssolui Glee dob of New York. Printed

here by permission.

[march, O march, O march de an-g-el marchIO, my soul, a- rise in

Heav-cn, Lord, For to year- de when Jor- dan roll. O roll.

'Parson Fuller," "Deacon Henshaw,' "Brndder Mosey," "Massa Linkum," - etc. 2. LitUe chil'en, learn to fear de Lord, i 3. O, let no false nor spiteful Word And let your days be long"; Be found upon your tongTie;

Roll, Jordan, etc. ' RoU, Jordan, etc.

Words and melody from "Slave Songs of tte uiited States!' Arranged for "»en ArtojSes for the Mendelssohn Glee Club of New York, and published here by permiss.oa It is an interesting example of the use of the flat seventn

---------------------------------------------------------

Ma mourri

Mo con-nin, zins zens, ma mour-ri,

Well I kno'^, young' men, I must die.

oui, 'no - cent,

yes, era - zy.

ma moor- ri; Mo oon-nin, zins zens, mamonr>ri 'no-cent, onl, ^o-cent,

I most die; Well I know.young'men, I must, era- zy, die, yes, cra-z^

ma monr-ri.

I must die.

Ehhlit fou' la belle La-yotte 'ma mour-ri 'no-oent,

Ehhhl For the fair La-yotte I must cra-zy die.

oui, 'no- cent, ma mour-ri. Ma con-nin, zins zens, ma monr-iit

yes, cra-zy, I must die. Well I know,yoiing'men, I must 4ie,

ma moor- ri 'no- cent, ma mour.- ri pan' la belle La-yottel

I must, cra-zy, die, I must die for the fair La-ydttel

"Words and music from the"Century Magazine"of February, 1886, where credit for the arrangement was inadvertently given to the author; it belongs to John VaaBroeUiovtoj. The translation is Mr. Cable's.

----------------------------------------------------------

Martinique Love-Song

menme I'an - mon, Ou - ve la pote ha moin.» To, to, to!

To, to, to!

Ca qui la?

C'est moin-menme I'annion,

Ouve la pote ba moi^.

To, to, to!

ga qui la?

C'est moin-menme I'anmou,

Xa plie ka mouille moin.

To, to, to!

Ca qui la?

C'est moin-menme I'anmou,

Qui ka ba on rhe moin!

Tap, tap, tap!

Who taps there?

'Tis iny own self, love,

Opea the door for me.

Tap, tap, tap!

Who f.aps there?

'Tis my own self, love,

The rain is wetting' me.

Tap, tap, tap!

Who taps there?

'Tis my own self,love.

Who g-ive my heart to theel

Collected for the author by Laf cadio Hearn, who says of it in his "Two Years in the French West Indies": "'To, to, to' is very old- dates back, perhaps, to the time of the belles-affrantMea, It is seldom sung now except by survivors of the old regime: the sincerity and tenderness of the emotion that inspired it- the old sweetness of heart and simplicity of thought/- are pass-

ing for ever away." The arrangement was made by Frank vin der Stucken and is here reprinted; permission of Harper & Bros.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Emgann Sant-Kast (The Battle of St. Cast)

Fa Tann koos - ket, enn_ noz vez all, E kle viz

mgfat fell a • round me, deep in my sleep I heard the

son ar t!hom - Ini hal,

tnim>pet loud re • peat,

Son ar (^hom • bu - hal,

Thro' hall and for • est

e ko - at ■ sal:

rang' the_ call:

"Hoi Sao-zont Sao - zoni- Sao . zon fall!"

"Curs'd be the Saz.ons,. Saz-ons aUI"

Rhyvelgyrch Cadpen Morgan (Captam Morgan's March)

Hhwym wrth dy wre - gjs, gledd - yf gwyn dy dad;

Forth to the hat . tlel on - ward to the fig-htl

Mwg' y pen - tref ydd gyf - yd gyd • a'r gwynt,

Let not the sun • light o'er our path - way dose.

At ynt fy mach-gen! tros dy wlad. Sych dy ddag-rau,

Swift as the ea - gle in his flightl Strong* as yon - der

Draw dy gy-mrod - yr Snt yn gynt. Wrth dy fv - a,

Till we o'er-lhrow our Sax- on foes. Be ye read-y,

1 - dy gyf-rwy iuud,QwTandoVsaeth-anii sn - o fel seirph di-baid;

foaining"— tide, Bush - iog'_ down- the moun-taiu-sidei

IgmwnaHhfi^diyn gref, Cof- ia am if dad, fel ba far - w efl

swotdand_ spear, Four- up - oa — the spoil- er near!

--------------------------------------------------------

INDEX

Acadian Boat-Song, SI, 54.

Adelelmo, 59.

African travellers, musically illiterate, 13; idioms in American folksongs, 22; music, 56 f< seq.; music characterized, 60; recitative in, 100; languages, survival of words from, 128.

Agwas, 57.

Aida, Oriental melodies from, 87.

Ain't I glad I got out of the Wilderness,

Albe'rtini, 59.

Alia zoppa, 94,

Allen, William Francis, vi, 29,32, 34,

43, 81, 97, 111, 129.

American Folk-Lore Society, viii; Indian music, 51.

Americans, what are they?, 26.

And I yearde from heaven to-day, 103.

Aridas, 57.

Ashantee music, 61.

Ashley, Thomas, quoted, 143.

Asra, Der, song by Rubinstein, 87.

Atlantic Monthly, quoted, 43.

Aurore Pradere, 123.

Awassas, 57.

Babouille, dance, 116.

Bach, Sonata in E, 15.

Bacon, Theodore, "Some Breton Folksongs," 9.

Balatpi, songs of the, 101.

Balboa, his ships built by negroes, 26.

Ballets, 16.

Baltimore Gals, 15.

Bamboula, dance, 116.

Barzaz-Breiz, 9.

Battle-Cry of Freedom, 17, 23.

Bechuanas, 60.

Bede, the Venerable, 36,

Beethoven, use of the major sixth

in minor, 81.

Bele, dance, 66, 116.

Sell da Ring, 49.

Benguin, dance, 116.

Bescherelle, quoted, 116,

Biblical allusions in songs, 45.

Blanchisseuses of St. Pierre, their

songs, 144.

Bongo negroes, songs and dances of, 44, 113.

Bornou, song in praise of the Sultan of, 102,

Bouene, dance, 116,

Bowditch, "Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee," 60, 62.

Brittany, folksongs of, 9.

Bryant's Minstrels, 33.

Buchner, Max, "Kamerun," quoted, 67.

Buffalo Gals, IS.

Bulgarians, folksongs of the, 7.

Burial customs of the Africans and slaves, 103 et seq.

Burleigh, Henry T., his help acknowledged, viii,

Burney, Dr. Charles, quoted, 72.

Burtchell, W. T., "Travels in the Interior of Africa," quoted, 60.

Burton, Richard F., "Lake Regions of Central Africa," quoted, 44, 57, 101.

Busch, Moritz, "Wanderungen zwischen Hudson und Mississippi," quoted, 12

Cable, George W,, credited and quoted, viii, 38, 40, 138, 141.

Calhoun School Collection of Plantation Songs, quoted, 43, 71, 82, 87.

Calinda {and Caleinda), a dance, 66, 67, 116.

Cameron, Verney Lovett, "Across Africa," quoted, 101, 113.

Camptown Races, 16.

Canada, folksongs of, vi, 22.

Can't stay behind, 49.

Capello and Ivens, "From Benguela to the Territory of Yucca, "quoted, 113.

Captain Morgan's March, 10, 169.

Carnival celebration and songs in Louisiana and the French West Indies, 141 et seq.

Caroline, 138, 139.

Cassuto, 121.

Cata {or Chata), a dance, 116.

Century Company and Magazine, credited and quoted, viii, 30, 38, 40, 138, 152.

Chad wick,_ George W., writes American music, V.

Charleston Gals, 15.

China, use of pentatonic scale in its music, 7; a missionary's experience with hymns, 76.

Christy's Minstrels, 12, 15.

Classification of Slave Songs, 140.

Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel, composer, 44, 47, 59, 73.

Collections of Slave Songs, 42, 43.

Columbus, negroes come with him to America, 26.

Combat de Saint-Cast, 9, 169.

Come tremble-ing down, 84, 85, 87,

Congo, a dance, 126.

Congos, their music, 57.

Continental Monthly, quoted, 43.

Coon songs, 2, 16.

Cotolies, 57.

Counjai (or Counjaille), a dance, 116 et seq.

Creole, meaning of the term, 134; grammar of the patois, 127 et seq.; songs of, 35, 37, 38 et seq.; use of satire, 140.

Criole candjo, 116, 118.

Cruelty to slaves, 25.

Cui, Cesar, on Russian folksongs, 7. Dahomans, 60, 61, 67, 77, 79; death customs of, 108; dances of, 133.

Dances of the American negroes, 95, 112 et seq.

Dandy Jim of Caroline, 16.

Daudet, Alphonse, his use of a Creole song, 135.

Day, Charles William, "Five Years' Residence in the West Indies," quoted, 12.

Denham and Clapperton, "Narrative of Travels in Northern and Central Africa," quoted, 102.

Denmark, folksongs of, 5.

Dese all my fader's children, 108.

Dessan mouilldge, etc., a Martinique dance, 125, 126.

Devil, in Carnival dances of Martinique, 145.

Devil songs, 16, 34.

Dig my Grave, 103, 104.

Dimitry, Alexander, 40.

Dixie, 33.

Done ztiid driber's dribin', 17, 19.

Drums and drumming, 61, 65; as signals, 65; in Martinique, 66; in Unyanebe, 67; in New Orleans, 67; in Voodoo, Congo and Calinda dances, 67; in Kamerun, 67; in Bashilonga, 67.

Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt, "The Souls of Black Folk," quoted, vi, 17; on the negro in America, 27; 43.

Du Chaillu, Paul B., "Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa," quoted, 106.

Dvorak, Antonin, use of American idioms, iv; 153 et seq.

Edwards, Bryan, "The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies," quoted, 106, 107.

Edwards, Charles L., 36; "Bahama Songs and Stories," 43, 106, 107, 128, 140.

Ein Lammlein geht und tragi die Schuld, 58.

Emancipation, songs of, 17 et seq,

Emgann Sant-Kast, 169.

Emmet, Dan, 33.

Endemann, K., "Mittheilungen uber die Sotho-Neger," 106.

Engel, Carl, "Introduction to the Study of National Music," quoted 5, 44, 77, 87, 102, 143.

Exposure of slaves, 24.

Fantees, music of, 62.

Father Abraham, 87, 90.

FcCQRS 5/

Fenner, Thomas P., 42, 71.

Fescennine verses of the Romans, 141.

Fetich man's fortune-telling, 101.

Fiddle sings, 16, 34.

Fillmore, John C., 65.

Finland, folksongs of, 5, 7; racial relation of its people, 7; its Orpheus, 8; its epic, 8; its runo songs, 8.

Fisk Jubilee Singers and their Collection, 16, 17, 42, 71, 82, 84, 91, 95.

Five-four time, 8.

Folkdances, rhythms of, 6.

Folksongs defined, 2; how composed, 3, 4, 23; parallelisms between, 14; are the American slave songs folk-songs.', 26 et seq.; of Sweden, 5; Russia, 5; Norway, 5; Wallachia, 5; Denmark, 5; Finland, 5; Serbs, 7; Bulgarians, 7; Montene-

grins, 7; Bretons, 9; Canadians, 22; created by national crises, 23.

Fonda, 57.

Forten, Miss Charlotte L., quoted, 49.

Foster, Stephen C, 16.

Fourth, the interval omitted, 69, 70.

Fowler, Prof. Henry T., "History of the Literature of Ancient Israel," quoted, 140.

Freely go, marching along, 87, 88.

Friedenthal, Albert, "Musik, Tanz und Dichtung bei den Kreolen Amerikas," quoted, 38, 59, 68, 93, 114.

Funeral music and customs, 103 et seq.

Gigueiroa, 59.

Gluck, Che faro senza Euridice, 57.

Gottschalk, his use of a Creole melody, 135.

Grant, James Augustus, "A Walk Across Africa," quoted, 46, 67.

Great Campmeetin', 71, 77, 78, 79.

Gregorian Chant, conservatism regarding the, 37.

Grimm, on the origin of folksongs, 3.

Griots, 38, 143.

Grout, the Rev. Louis, "Zulu-Land, etc.", quoted, 101.

Grove, "Dictionary of Music and Musicians," quoted, 76, 92.

Guehues, African minstrels, 143.

Guiouba {or Juba), dance, 116.

Gwine follow, IS.

Habanera, dance, 59, 68, 93, 114, 115.

Hahn, Theophilus, quoted, 58.

Hallowell, Miss Emily, quoted, viii, 71, 82, 91.

Hampton Institute and Collection of Songs, 21, 30, 42, 91, 97.

Handel, Dead march in "Saul," 44.

Hard Trials, 71.

Harmony in African and slave music, 60, 64, 81.

Harper & Brothers, acknowledgement to, viii.

Haskell, Marion Alexander, quoted,30.

Haytian dances, 94.

Hearn, Lafcadio, his letters, and "Two Years in the French West Indies," quoted, 35, 37, 47, 55, 66, 121, 125, 134, 135, 141, 144, 145, 149, 151.

Heaven bell a-ring, 49.

Hebrew music, 7.

Hiawatha, 8.

Higginson, Col. Thomas Wentworth, vi; quoted, 17, 21, 23, 29, 43, 44, 45, 49, 50, 109.

Hill, Miss Mildred J., quoted, 32, 72, 91.

Hiuen, Chinese instrument, 74.

Holub, Dr., "Seven Years in South Africa," quoted, 113.

Hook, quoted, 93.

Ho, round the corn, Sally, 48, 128.

Hottentots, singing of, 58, 60, 61.

Hughes, Rupert, "The Musical Guide," quoted, 2.

Hungary, folk-music of, 87.

Huss, Henry Holden, acknowledgement to, 8.

Iboes, 57.

Idioms of folksongs, '56 et seq.

I Know Moonlight, 109.

/ Look o'er Yander, 103, 105, 107.

Fm gwine to Alabamy, 51, 52.

Imitations in songs of American negroes, 14 et seq.

Imitative capacity of negroes, 58.

In bright mansions above, 16.

Indians, American, their pentatonic scale. 7; their songs, 72.

Influence of Negro music on American peoples, 59.

Instruments, African, 68.

Intrepides, Martinique dancing society, 145.

I saw the beam in my sister's eye, 15.

Israelitish taunt and triumph songs, 141.

I want to be my Fader's chil'en, 102.

Jackson, Miss, original Jubilee singer, 84.

Japan, pentatonic scale in, 7.

Jesus heal' de sick, 160.

Jews, their synagogal music, 7.

Jim Crow songs, 34.

Jiminez, pianist, 59.

Jine 'em, 49.

Jubilee Singers of Fisk University. (See Fisk.)

Jump Jim Crow, 16.

Kaffirs, music of 61; singing of, 82.

Kaleivala, Finnish epic, 8.

Kantele, Finnish harp, 8.

Kemble, Mrs. Frances Anne, "Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation," 46, 154.

Kidson, Frank, on the pentatonic scale, 76.

Kolbe, Peter, "Caput Bonae Spei Hodiernum," quoted, 60.

Kolo dance of Servians, 77.

Korrigan, 10.

Koundjo, 116 et seq.

Kroeger, Edward R., v.

Kroomen, music of, 57.

Labat, Pere, quoted, 66.

Laing, Major A. G., "Travels in Western Africa," 106.

Language, forgotten, 36; corrupted by slaves, 127 et seq.

Lashash, Soudanese minstrels, 143.

Lay this body down, 49.

Leading-tone (seventh), 84.

Lewis, M. G., "A Journal of a Residence among the Negroes of the West Indies," quoted, 25.

Lily Dale, 17.

Lippincott's Magazine, quoted, 107.

Livingstone, quoted, 121.

Loema tomb'e, 141, 149, 150.

Longfellow, "Hiawatha," 8.

Lyon, George Francis, "Narrative of Travels in Northern Africa," quoted, 46.

Mabunda, dance, 113.

McKim, Miller, quoted, 24.

McKim, Miss Lucy, quoted, 12, 71.

McLeod, Norman, on Irish music, 6.

Macrum, W., song quoted, 120.

Magyars (Hungarians), rhythm of their songs, 6; are Scythians, 7; their music, 87, 94.

Mahrchen, 1.

Major Mode, a symbol of gayety, 4; in Russia, 7; prevalence of 5; in negro songs, 43et seq.i variations of, 70 et seq.

Makalaka, 101.

Malagasy, rhythms of, 97.

Ma mourri, 167.

Manmam Colette, Martinique dance, 125, 126.

Manyuema, dances of, 113.

Many thousand go, 17, 18.

Many thousands gone, 17, 20.

Marching through Georgia, 23.

Marie-Clemence, 146, 147.

Marimba, 68.

Marriage forbidden to black Creoles, 138.

Marsh, J. B. T., "Story of the Jubilee Singers," 42.

Martinique, dances, 125, 126.

Mauch, Carl, "Reisen in Siid-Afrika," quoted, 101.

Meens, 57.

Mees, Arthur, credited, vii; on the flat seventh and harmony, 79.

Melancholy in folkmusic, 5.

Mercier, Dr. Alfred, "Etude sur la Langue Creole en Louisiane," quoted, 130 et seq.

Meringue, Haytian dance, 94.

Michael row the boat ashore, 49.

Michie Prhal, 141, 151, 152.

Minor Mode, a symbol of gravity, 4; prevalence! 5; 29, 30; 43 et seq,; 70, 83 et seq.; sixth omitted in scale, 70, 84; leading-tone in, 84.

Mixolydian mode, 77, 79.

Modes of slave songs in America, 43 et seq.

Mohr, Eduard, "Nach den Victoria- fallen des Zambesi," quoted, 101.

Moloney, A. C, "Notes on Yoruba, etc.," quoted, 66.

Moodie, John W. D., "Ten Years in South Africa," quoted, 57.

Moors, as slaves, 57.

Mother, is Massa gwine to sell us tomorrow?, 17.

Moton, Robert R., 30.

Murphy, Mrs. Jeannette Robinson, quoted, 82, 108.

Musieu Bainjo, 141, 142.

Musikalisches Wochenblatt, quoted, 94.

My Heart's in the Highlands, 58.

Nagos, 57.

"Nation, The," quoted, 33.

Negroes in America, 26, 27; census reports, 27.

Neve' a man speak like this man, 159.

Niam-Niam minstrels, 64, 143.

Nobody knows the trouble I see, 74, 75, 96, 164.

Nocturnal songs and dances, 103.

No Man, 49.

No more peck of corn, 18, 23.

Norway, folksongs of, 5.

O du lieber Augustin, 58.

O'er the Crossing, 97, 98, 128.

O Graveyard, 109, 110.

O Haupt voll Blut und fFunden, 58.

Oh, Freedom over me, 17.

0, Rock me, Julie, 51, 52.

Ole Virginny n'ebher tire, 15.

Opon de Rock, 162.

Oriental scale, 87, 9L

Ou beau di main tete, Martinique dance, 125, 126.

Paloma, La, Mexican song, 115.

Parallelisms between folksongs, 14.

Pauv' ti Lele, 135.

Peabody, Charles, on working songs, 47.

Pentatonic scale, 7, 43, 69, 70, 73 et seq.

Pillard, satirical song of the Creoles, 141 et seq.

Pitch, frequently vague in the singing of slaves, 70 et seq.

Plain-Song, 64.

Plantation Life, influence of, 22.

Plato and the sacred chants of the Egyptians, 36.

Plattsburg, battle of, 16.

Poles, folksongs of, 87.

Popos, 57.

Pov' piti Lolotte, 135, 136.

Praise Member, 49.

Proyart, Abbe, "History of Loango, Kakongo, etc.," quoted, 107.

Ragtime, iii: 2, 6, 48, 92, 93.

Rain fall and wet Becky Martin, 49, 50.

Rakoczky March, 46, 87.

Ranz des Vaches prohibited, 46.

Reade, W. Winwood, "The African Sketchbook," quoted, 47.

Recitative in African song, 100 et seq.

"Reel Tunes," 16.

Reid, Ogden Mills, Editor of the N. Y. Tribune, acknowledgements to, viii.

Religion and music, 9, 29.

Religion so sweet, 49.

Religious character of the plantation folksongs, 42.

Remon, Rimon, 122.

Rhythm and rhythmical distortions, 6,95.

Rkyvelgyrck Cadpen Morgan, 10, 169.

Rice, "Daddy," 16.

Richardson, the Rev. J., quoted, 97.

River, roustabout and rowing songs, 34, 48, 49, 51.

Roche, Louise, 38, 39.

Roll, Jordan, roll, 102, 165.

Romaika, 33.

Roosevelt, Theodore, 92.

Root, George F., The Battle-Cry of Freedom, 17.

Round about the mountain, 63.

Runo songs of the Finns, 8.

Russell, W. H., "My Diary, North and South," quoted, 111.

Russia, folksongs of, 5; influence of suffering, 6; dances, 6.

Saint-Cast, Battle of, 9, 169.

Salas, Brindis de, 59.

Sanko, African instrument, 62.

Sanskrit prayers in China, 36.

Sans-Souci, Martinique dancing society, 145.

Satire in songs of the Creoles, 140 et seq.

Scales, origin of, 91_; Oriental, 91.

Schauenburg, "Reisen ia Central- Afrika," quoted, 66.

Schweinfurth, Dr. Georg, "Heart of Afrika," quoted, 64, 113.

Scotch songs, 83.

Second, the augmented interval in folksongs, 7, 84.

Secular songs, paucity of, among American slave songs, 28, 34.

Serbs, augmented second in their music, 7.

"Settin' up" in the Bahamas, 107.

Seventh (interval), flatted, 69, 70, 71; omitted, 69, 70; raised to leading-tone in minor, 69.

Seward, Theodore F., 42, 95.

Shamans of the North American Indians, 107.

Shock along, John, 48.

"Shout" and "Shouting," 32 ei seq.; 95, 106, 109, 112.

Sibree, the Rev. Tames W., quoted, 97.

Sierra Leone, singing of the negroes in, 44, 60.

Silcher, Friedrich, Zu Strassburg auf der Schanz, 2; Ich teeiss nicht, was soil es bedeuten, 2.

Sixth (interval), major in minor scales, 69, 70, 81, 84; omitted, 69,

Slavery in America, 36, 56 et seq.

Slaves, American, not all negroes, 56.

"Slave Songs of the United States" (collection), vi, 16, 17, 26, 29, 32, 34, 42, 43, 48, 49, 50, 53, 71, 81, 91, 97, 100, 109, 116, 121, 138.

Smith, Captain John, on rattles in Virginia, 13.

Snap (Scots', Scotch, Scottish, etc.), 6, 48, 68, 83, 92 et seq., 135.

Socos, 57.

Some come cripple, 158.

Soyaux, Hermann, "Aus West-Afrika," quoted, 44, 60.

Spanish melody on African rhythm, 83.

Spaulding, H. G., credit, vi; "Under the Palmetto," quoted, 12, 17, 43.

Spencer, Herbert, his theory on the origin of music, 3, 4, 29.

Spirituals, 16.

Spohr, Louis, on intervals in folk- song, 72.

Squire, Irving, "American History and Encyclopsedia of Music," quoted, 47.

Strathspey reel, 92.

Structural forms of the Afro-Ameri- can folksongs, 100 et seq.

Suffering, provocative of folksong, 4.

Sweden, folksongs of, 5.

Take him to the gully, 24.

Tango, 93, 114.

Tant sirop est doux, 116, 117.

Tiersot, Julien, his monograph on American folksongs, quoted, vi, 32, 35, 36, 84, 135, 138.

Tomlinson, Reuben, 50.

To, to, to, 166.

Tramp, tramp, tramp, 23,

Tribune, New York newspaper, credited, iii, iv.

Triple time in negro songs, 95.

Trowbridge, Col., quoted, 50.

Tschaikowsky, "Pathetic" symphony, 8.

Turiault, "Etude sur la Langue Creole," quoted, 40.

Turkey-trot, 93, 114.

Valdez, Francisco Travassos, "Six Years of a Traveler's Life in West- ern Africa," quoted, 106.

Van Broekhoven, John A., acknowledgments to, viii.

Variations from conventional scales, 68.

Villemarque, Th. Heraart de la, Barzaz-Breiz, 9.

Volkslied, 1.

Volksthiimliches Lied, 1.

Fologeso, Italian opera, 92.

Voodoo songs, 35, 37, 40, 67.

Wachtel, Dr. Aurel, quoted, 74.

Wagner, Nibelung rhythm in Africa, S8.

Wainamoinen, Finnish Orpheus, 8.

Waitz, Theodor, "Anthropologie der Naturvolker," 106.

Wallachia, folksongs of, S.

Wallaschek, Dr. Richard, "Primi- tive Music," 11; his arguments traversed, l\ et seq.; a careless in- vestigator, 12; 46, 47, 57, 58, 59, 60, 115, 121.

Wangemann, Dr., 82.

Ware, Charles Pickard, 49.

Washington, Booker T., vi, 47.

Wearing of the Green, 16.

Weber, Carl Maria von, JVir winden dir, 2,

Weber, Ernst von, "Vier Jahre in Afrika," quoted; 101.

Weeping Mary, 80, 81, 157.

Weissmann, Hermann, "Unter deut- scher Flaggedurch Afrika," quoted, 67.

We'll soon be free, 21.

Welsh and Bretons, 9, 10.

Wentworth, the Rev. Dr., 76.

Wesley, the Rev. John, on the Devil and good tunes, 34.

White, George L., manager of the Jubilee Singers, 42, 82.

White, Jose, violinist, 59.

Who is on the Lord's side?, 16.

Whole-tone scale, 51.

Wood, J. Muir, 72.

Woodville, Jenny, quoted, 107.

Working songs of the slaves, 46 et seq.

Wulsin, Mrs., her copy of an Acadian song, 51.

You may bury me in the east, 31, 84, 86.

Zanze, African instrument, 61, 68, 74.

Ziehn, Bernhard, "Harmonielehre," quoted, 81.

Zip Coon, IS.

Zoellner, Heinrich, quoted, 77.

Zombi, 40.

Zulu-Kafirs, songs of, 101.

Zuni Indians, singing of, 72.

[