8G. Madam, I Have Gold and Silver (Folk Plays)

A. "Plough Monday Play" recreated from tradition about 1860 by Uncle Joe and Aunt Mary of Craney Creek, Kentucky. Collected by about 1930 Marie Campbell and published in JAF, 1938.

B. "Plough Jags," taken from Elsham-Brigg of Lincoln learned about 1880. From James Madison Carpenter and the Mummers' Play by Steve Roud and Paul Smith (Folk Music Journal, Vol. 7, No. 4, Special Issue on the James Madison Carpenter Collection (1998), pp. 496-513).

C. "Brattleby, Lincolnshire Mummers' Play" from Mrs E.H.Rudkin Collection. The words were noted by Alice Wright while the mummers still played about 1894. They were preserved In a Family Scrap Album.

D. "Kirmington Plough-Jags Play," from Kirmington, Lincolnshire as published in R.J.E. Tiddy's "The Mummers' Play" Oxford, University Press, 1923, pp. 254-257. According to Greig: "This particular play seems to have been added to Tiddy's collection by Rupert Thomson, who edited the book for publication after the author was killed in action on August 10th, 1916."

E. "Carlton-Le-Moorland Ploughboys," dated 1934; from Lincolnshire Plough Plays by E. H. Rudkin from Folklore, Vol. 50, No. 1 (Mar., 1939), pp. 88-97.

F. "Barrow-on-Humber Plough Play," from a MS in M. W. Barley Collection, University of Nottingham Library. Performed at the Festival of Britain Pageant at Barrow-on-Humber, Lincolnshire, 1951.

G. "Coleby Plough-Jag," recreated from an earlier tradition in 1974 by M.C. Ogg of Coleby, Lincolnshire from information by Mr. Roly Redhead of Burton on Stather and Mr. Arthur Gelder of Alkboro' Lane.

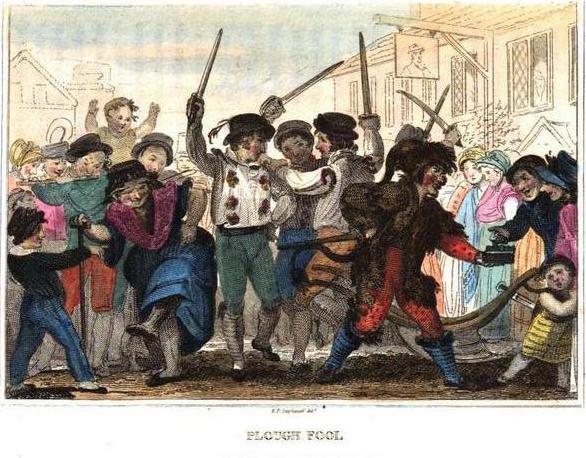

[Stanzas of "Madam, I Have Come to Court You" (hereafter "Madam") have been used in British folk plays and one play collected in Kentucky. The texts of these plays were written down in the early 1900s but date well into the 1800s[1]. The British folk plays that had stanzas of Madam were known as "Plough plays" which were performed on Plough Monday (the first Monday after January 6th which is also known as "Old Christmas" or Epiphany-- the celebration of "Twelfth Night" is on the eve of "Old Christmas") by rural farmers, land owners, farms hands and laboreres who received donations of money and or refreshments for their performances. These plays in some form have been traced to the late 1700s but the standard, Recruiting Sergeant play[2], where stanzas of "Madam" are present, was popular during the mid-1800s until the First World War in Lincolnshire and surrounding areas. Two children's game songs titled "Lady on Yonder Hill" published by Gomme in 1894[3] mimic actions of the Recruiting Sergeant play (see 8C. On a Mountain Stands a Lady). The opening stanza of "Lady on Yonder Hill" is constructed from text of "Madam" although the children's games stanza is different than those found in the folk plays. It is likely that the children's British game songs were recreated from the stanzas of "Madam" found in the British folk plays since they both have the "nice young man" line in common while Madam has "handsome man"-- a significant difference.

The British folk plays, once generically called "Mummers Plays[4]," are part of a group of archaic skits or plays that were performed at "revels" around Christmas and other holidays. In some of the plays the action is centered around the courtship of a "lady bright" and these have been called "wooing plays[5]" or "Plough Plays" and specifically the Recruiting Sergeant type play. One common theory of their origin is that the actors known as mummers' or guisers' (disguisers) developed their plays from ancient pagan fertility rituals[6]. Evidence of the mummers' or guisers' acting out skits or plays dates at least back to 1296 in England[7]. However, it was not until the late 1700s that written scripts of these folk plays appeared. It has been suggested by Millington and others that the Plough Plays possibly had a Danish origin (see: "The Origins of Plough Monday" by P.T.Millington) but that discussion is beyond the scope of this brief study. The Recruiting Sergeant plays with stanzas of "Madam," although popular in the 1800s, were not written down until the early 1900s (see as exceptions the E. Andrew Elsham-Brigg version that dates to circa 1880 and Brattleby, Lincolnshire Mummers' Play of 1894-- both were discovered in the 1900s and published after the 1960s).

Concrete evidence that the modern[8] folk plays were performed during the Elizabethan Era (from 1558–1603, the reign of Queen Elizabeth I) is lacking. Speculation by Baskerville and others about these "wooing plays" being a product of the Elizabethan Stage Jig, which were performed by locals usually in costume during intermission of various plays, has created the myth that wooing songs such as those with stanzas of "Madam" were performed during the Elizabethan Era. As evidence that the folk plays existed during this time, Baskerville quotes a passage from the Induction of The Taming of the Shrew (1593). The lines that follow are spoken by a Lord who is addressing a group of traveling players staying at his estate. The Lord says to Player 2:

"This fellow I remember,

Since once he played a farmer's eldest son.

'Twas where you wooed the gentlewoman so well."

As Baskervill points out, this appears to be a reference to an archaic wooing play with the common role of farmer's eldest son (or eldest son) as found in "wooing plays" of the 1800s and early 1900s. Although the lines from Taming of the Shrew seem to indicate the early existence of a Recruiting Sergeant type play, Millington and others have largely debunked the concept that the "wooing" plays of the 1800 and 1900s were, in fact, based on plays from the 1500s and 1600s. The obvious reason is: the plays of the 1500s and 1600s were not written down and no detailed record of their contents exists. According to Millington[9], "The earliest play for which we have a text is a chapbook published in Newcastle by J. White. This is undated, but research into the book trade has indicated that it must have been published sometime between 1746 and 1769." It was a play titled "Alexander, and the King of Egypt. A Mock Play As it is Acted by The Mummers every Christmas." Since no written record was made of the early plays from the 1500s and 1600s, no comparison may be made. Millington has organized the "modern" folk plays into four main categories[10]:

1) The Hero/Combat play.

2) The Recruiting Sergeant play

3) The Wooing play

4) The Sword Dance play,

Stanzas of "Madam" have been found in several plays of the Recruiting Sergeant type. These plays have their with roots in the 1800s and were published in the early to mid 1900s. Again it is prudent to capitulate: there is no evidence that these stanzas of "Madam" found in the written scripts of the "Wooing Plays" of the early 1900s in the UK and US were ever part of the archaic "Mummers' Plays" which sprang from the ancient pagan marriage customs of old England or that they descended from the Elizabethan Stage Jig. "The Wooing Plays" also know as "Plough Plays" or "Pough Jags[11]" were first analyzed in detail in Baskervill's 1924 article, "Mummers' Wooing Plays in England." Evidence of these Plough plays is found in the late 1700s although details of earlier scripts are wanting[12].

In his article Baskervill mentions two children's songs (see: 8C. On the Mountain Stands a Lady) titled "Lady on Yonder Hill" by Gomme (see: Traditional Games, I, 323-24) which mimic the actions of the "plough plays." Baskervill comments:

In the Derbyshire version, with an opening "Yonder stands a lovely lady," like a line in the Bassingham plays printed below, the rebuffed wooer falls on the ground and is revived by the Good Fairy. In the Suffolk version the Gentleman stabs the Lady and then revives her, calling her out of her trance with lines similar to the corresponding lines in the Bassingham, Cropwell, and Axholme plays.

The identifying stanza of "Yonder Stands a lovely Lady" is also made up of text from 8. "Madam I have Come to Court You." However, it's the "gold and silver" stanzas which are found in the dialogue of several Plough Plays both in the UK and US.

The Plough Plays are part of a larger group of folk plays once generically called The Mummers Plays. These wooing plays have more recently been renamed "Quack Doctor Plays" by Peter Millington and are further grouped by the names of the dominant characters in the plays, such as the "Recruiting Sergeant" who frequently sing the "Madam, I have gold and silver" stanza. In his article "Textual Analysis of English Quack Doctor Plays: Some New Discoveries," Millington says:

Various proposals have been made regarding specific aspects of the folk play tradition, but they have not been assembled into a cohesive whole. There are five main points.

a) It seems likely that the plays were added to pre-existing house-visiting customs, and that this took place sometime during the early to mid 18th century, as an extension of the entertainments that these customs already possessed.

b) Pettitt (1981 & 1994) and Fees (1994) have demonstrated that drama in the community was varied in the 18th and 19th centuries.

c) There is some evidence that the Quack Doctor plays indirectly took up the theatrical conventions of the Commedia dell’ Arte, in terms of verse scripts, dramaturgy and costume.

d) The overall similarity of the scripts suggests that there ought to be a single proto-text from which all the various versions developed. However, there has hitherto been no attempt to characterise or locate such a proto-text.

e) Regardless of how the Quack Doctor plays originated, they seem to have spread very rapidly to most of Britain and diversified very early on in their history.

The fundamental stanzas of "Madam" in the folk plays are found similarly in the earliest extant version of "Madam," titled "The Lovely Creature" ("Yonder sits a Lovely Creature"), which was printed at Aldermary Churchyard by one of the Dicey/Marshall dynasty and is dated about 1760[13]. It comes from British Library 11621 e 6, items 1 to 26, which are a variety of songsters, and is mostly material sung at the various London pleasure gardens such as Vauxhall. Here is the text:

1. Yonder sits a lovely creature,

Who is she? I do not know,

I'll go court her for her features,

Whether her answer be "Ay" or "no."

2. "Madam, I am come to court you,

If your favor I can gain,

Madam if you kindly use me,

May be I may call again."

3. Well done," said she, "Thou art a brave fellow,

If your face I'll ne'er see more,

I must and I will have a handsome young fellow,

Altho' it keep me mean and poor.

4. "Madam I have rings and diamonds,

Madam I have got houses and lands

Madam I've got a world of treasure,

All shall be at your command."

5. What care I for rings and diamonds?

What care I for houses and lands?

What care I for worlds of treasure?

So I have but a handsome man."

6. Madam, you talk much of beauty,

Beauty it will fade away,

The prettiest flower that grows in summer,

Will decay and fall away.

7. First spring cowslips then spring daisies,

First comes night love, then comes day,

First comes an old love then comes a new one,

So we pass the time away.

Stanzas 4 and 5 are the fundamental stanzas found in some of the folk plays of the 1800s. They are also present in a second early print version of "Madam" dated 1776, a broadside titled "A New Song":

"Madam I've got gold and treasure,

Madam I've got house and land

Madam I've got rings and jewels,

And all will be at your command."

What care I for gold and treasure,

What care I for house and land

What care I for rings and jewels,

If I had but a handsome man."

The line "Madam I've got gold and treasure," is also found as "Madam I've got gold and silver," which is how it commonly appears in the folk plays. The desire for a handsome young man is also found in 1823 the Bassingham Men's play performed during Christmas[14]:

Shepherdess: I will never marry with a cloud[clown]

But I will have a handsome young man

To lie in bed with me.

Later in the 1823 play are other lines that are similar to lines from "Madam":

The finishing Song

[Fool] Come write me down the power above

That first created A man to Love

I have a Diamond in my eye

Where all my Joy and comfort ly

I! give you Gold IV give you Pearl

If you can Fancy me my Girl

Rich Costley Robes you shall wear

If you can Fancy me my Dear

[Lady] Its not your Gold shall me entice

Leave of[f] Virtue to follow your advice

I do never intend at all

not to be at any Young Mans call.

Other early written plays also have lines similar to Madam. Here are a few lines from "Swinderby Decr. 31st 1842" Play (text from Baskerville):

[Fool.]

I will give your gold i will give the pirl

if thou can fancy me my girl)

[Lady.]

It is not your gold will me entice

to leave of roving to follow your advice

for I do never attend at all

to be at any young mans call

and later in the play she receives another offer:

[Ploughman?]

Madam if though will consent to marry me

I have got gold and silver and that will please the

thou shall have a servant maid to wait at thy command

and we will be married and married out of hand.

[Lady.]

O roger you are mistaken

a damsel i reside

I am in no such haste

as to be a ploughmans bride

I live hopes to gain a farmers son.

If there was an evolution from these similar stanzas to those taken directly from Madam, it seems to have occurred later in the 1800s. However, in the article "Plough Plays in the East Midlands" by M. W. Barley (Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Dec., 1953), pp. 82), he gives the following Lady Bright song and this information:

In addition to the usual song,

Behold the lady bright and gay

Good fortune and sweet charms,

So scornfully I've been thrown away

Right out of my true lover's arms;

He swears if I don't wed with him

As you will understand,

Hie'll go and list for a soldier

And go to some foreign land

the texts from Lusby, Branston and from the Bassingham group of villages also have the dialogue which has survived unchanged from the early nineteenth century, in which the wooer offers, unavailingly at first, gold and silver, house and land, rings and jewels.

The dialogue of the play mentioned by Barley where the wooer offers "gold and silver" obviously refers to the "gold and silver" stanzas found similarly in "Madam." Proof of Barley's assertion that these lines "remain unchanged" from the early 1800s has not been found.

Here's one early script with the Madam "gold and silver" stanzas as they appear sung in a folk play. The scene begins with an introduction by the "Lady Bright" which is followed by the Sergeant's Song and then the Lady's response. It's an excerpt taken from the 1923 "Plough Jacks’" play from Kirmington, Linconshire by R. J. E. Tiddy, pp. 254-257. This play dates back to at least 1916 by Rupert Thomson and was performed before World War I by Walter Brackenbury of Kirmington[15]:

Lady: I am a lady bright and fair

My fortune is my charms

It's true that I've been borne away

Out of my dear lover's arms,

He promised for to marry me

As you will understand,

He listed for a soldier

And went into foreign land.

{Sergeant's Song.}

Sergeant: Madam, I've got gold and silver

Madam I've got house and land

Madam I've got world and treasure,

Everything at thy command -

Lady: What care I for your gold and silver

What care I for your house and land?

What care I for your world and treasure

All I want is a nice young man.

The last line sung by the Lady has "nice young man" instead of "handsome man" a change that is also found in the children's game songs. The two stanzas are obviously the same stanzas found in the version of Madam dating back to the 1760s.

A very similar wooing dialogue and song was collected in the United States about 1930. In 1938 Marie Campbell wrote her article "Survivals of Old Folk Drama in the Kentucky Mountains" in The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. LI, No. 199. In her article Aunt Mary and Uncle Joe recalled "A Plough Monday Play" which they had not seen acted out in seventy years. To remember they "kept the play from falling out of their minds pineblank by saying it over to each other every little spell." This dates the Kentucky play circa 1860 and takes it to the mid to early 1800s in England. It compares similarly to the excerpt above:

Lady: In comes I, a lady fair,

My fortune in my charms.

It's true I've turned away

Out of my true-love's arms.

Oh, he did marry me,

As all do understand,

And then he listed for a soldier

In a far and distant land.

Soldier: Madam, I've got gold and silver,

Madam, I've got house and land,

Madam, I've got golden treasure,

All at your command.

Lady: What care I for your gold and silver?

What care I for your house and land?

What care I for your golden treasure?

All I want is a nice young man.

The earliest folk play in the UK I've found with stanzas of "Madam" is the Lincolnshire version collected by Carpenter from E. Andrew Elsham-Brigg that dates to circa 1880 although it was collected about 1934:

[LADY]: I am a lady bright and fair,

Me fortunes is me charms,

I was thrown away so scornfully

All from me lover's arms.

He promised for to marry me,

Which you will understand,

He listed for a soldier

And went to some foreign land.

SERGEANT: Madam, I've got gold and silver,

Madam, I've got house and land,

Madam, I've got worlds of treasure,

They are all at thy command (All will be at thy command)

LADY: What care I for thee gold or silver,

What care I for thee house and land,

What care I for thee worldly riches,

All I want is a nice young man.

FOOL: That's me, my dear!

LADY: Old man you are deceitful

As any of the rest.

But I shall have the young man

Which I do love the best.

This text is taken from the article, James Madison Carpenter and the Mummers' Play, by Steve Roud and Paul Smith in Folk Music Journal, Vol. 7, No. 4, (Special Issue on the James Madison Carpenter Collection, 1998, pp. 496-513). The typed text appeared in the Carpenter Collection with handwritten additions and corrections. This information was provided:

E. Andrew Elsham-Brigg, 71 years old. Learned fifty-five years ago, learned from older hands, in old shed. Went bit before Christmas time. Fool had long hat, two feet long, trimmed with paper, rags etc. Wore smock shirts, different colored stockings, face red and black etc. Soldier dressed like a soldier-Indian king, black with white smock and belt round him, wooden pistol and wooden sword, red cap.

A number of the entire folk plays will appear attached to the Records & Info page. Excerpts with the text from Madam will appear in the British & and Other Versions page and US & Canada Version page.

Another "Madam"stanza is found in the "Lincolnshire Plough Plays" by E. H. Rudkin (Folklore, Vol. 50, No. 1 (Mar., 1939), pp. 88-97). Rudkin gives the following stanza from a Linclonshire 1934 version sung by Carlton Le Mooreland Ploughboys-- the Fool sings:

A handsome man will not maintain you;

Beauty, it will fade away,

Like a rose that blooms in summer,

And in winter will decay.

This stanza and the "gold and silver" stanzas usually sung by the Recruiting Sergeant and Lady Bright characters are probably derived from the "Madam" print versions of the 1760s and 1770s. There is no indication that "Madam" was part of the folk plays before the 1800s. Both the children's songs of the late 1800s and the British folk plays have "nice young man" instead of "handsome man" found in the "Madam" print versions from the 1700s-- this indicates that the children's songs of the late 1800s were probably derived from versions of "Madam" sung in the folk plays.

R. Matteson 2017]

________________________________

Footnotes:

1. The earliest extant record I've found with the Madam stanzas in the UK is the Lincolnshire version collected by Carpenter from E. Andrew Elsham-Brigg that dates to circa 1880 although it was collected c. 1934. References by M. W. Barley in "Plough Plays in the East Midlands" that date the plays in England to the early 1800s are undocumented. The version from Kentucky published in 1938 (collected about 1930) was recreated from informants who learned the play in the late 1800s (c.1870). The play appears to have been communicated by Aunt Mary's grandfather was brought to Kentucky by his English ancestors which must have taken place a number of years earlier. A a date of early to mid-1800s for the Kentucky version is reasonable.

2. There are several early references but none giving the action of the play. I quote Millington's "The Origins of Plough Monday" (see-- http://www.petemillington.uk/ploughmonday/Origins.php) "Like folk plays, Plough Monday records are not very frequent prior to 1800, but unlike folk plays, there is a fairly good record at least back to the sixteenth century. Barley reviewed many of these early records, which are mostly drawn from wills and Parish registers (Barley, 1953). A feature of the older records is that they do not usually say what happened, and this is particularly so of the Plough Light records. The only thing which can be said with certainty about all these early records is that money changed hands. Although most of the older records are brief, several refer unequivocally to Plough Monday. For example there is a record of a court case dated 1597 in which ten men from North Muskham, Notts., were ordered to turn back the furrow they had ploughed across the church yard on "Plow Daie" (B.V.M., 1902)." [The Origins of Plough Monday by P.T.Millington]

3. One of four main types of folk play identified in "Mystery History: The Origins of British Mummers' Plays" by Peter Millington, Nottingham, England from "American Morris Newsletter," Nov./Dec.1989, Vol.13, No.3, pp.9-16.

4. Dictionary of British Folk-lore, Volume 1, edited by G. Laurence Gomme, 1894.

5. According ti Wiki, "The word mummer is sometimes explained to derive from Middle English mum ("silent") or Greek mommo ("mask"), but is more likely to be associated with Early New High German mummer ("disguised person", attested in Johann Fischart) and vermummen ("to wrap up, to disguise, to mask ones faces")."

6. The term "wooing play" has been attributed to Charles Read Baskerville whose article "Mummers' Wooing Plays in England" was published in 1924.

7. Millington has debunked this "pagan rituals" theory which comes from Baskerville ("Mummers' Wooing Plays in England"): "Though the mummers' play in which was enacted the wooing or marriage surviving from ancient pagan rituals in European folk lore generally was doubtless once a very popular form of folk drama in England, the wooing play is not recognized as a distinct type in the standard discussions of the mummers' plays by Ordish and Chambers."

8. From Lilian J. Redstone, Ipswich through the Ages (1969).. Ipswich: East Anglian Magazine Ltd. p. 110.

9. "Modern" refers to the Recruiting Sergeant folk plays with written scripts, which are not modern in the strict sense of the word since they died out in tradition by the Second World War.

10. See: "Mystery History: The Origins of British Mummers' Plays" by Peter Millington, Nottingham, England from "American Morris Newsletter," Nov./Dec.1989, Vol.13, No.3, pp.9-16.

11. Ibid.

12. The Plough plays are associated with the ancient festival of Plough Monday celebrated the first Monday after the Twelfth Night. "Jags" or "Jacks" refer to the players.

13. See "The Plough Play in Lincolnshire" by Ruairidh Greig.

14. This was dated by Steve Gardham from the original MS collection.

15.Text provided by Baskerville in "Mummers' Wooing Plays in England," 1924.

16. See: "The Kirmington Plough-Jags Play" by Ruairidh Greig.