2. The Drowsy Sleeper (Awake, Awake/ Bedroom Window/The Silver Dagger/O Katie Dear)

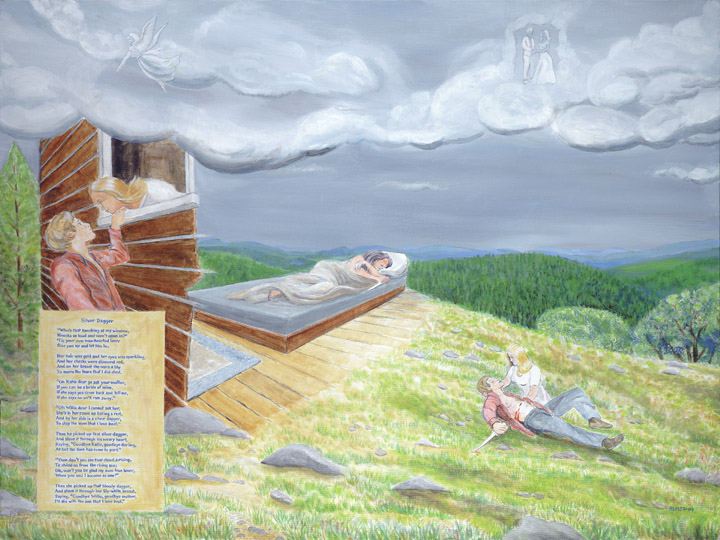

The "Silver Dagger" painting by Richard L. Matteson Jr. C2008

Narrative: No. 2 The Drowsy Sleeper

A. "Awake, thou fairest thing in nature." Song XCVII. Tea-table Miscellany: A Collection of Choice Songs, Scots & English; Volume 2 edited by Allan Ramsay c. 1725

Ba. "O Who is this under my window?" taken from Martha Crosbie, a carder and spinner of wool, by Alan Cunningham by 1809. Cunningham's recreation was published without credit in Cromek's "Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song, with Historical and Traditional Notices relative to the Manners and Customs of the Peasantry," 1810.

b. The partial traditional version was published in Alan Cunningham's Works of Robert Burns: With His Life, Volume 4, 1834.

C. [Four main British Broadsides c1817 to c.1863] Roud No: 22620.

a. "The Drowsy Sleeper" as published by J. Crome of Sheffield; c. 1817; Harding B 28(233)

b. "Cruel Father or the Maiden's Complaint" as published by J. Pitts of London c. 1820

c. "Maiden's Complaint" by T. Birt, London c. 1828

d. "Awake, Drowsy Sleeper" Firth c.17(25); H. Such of London c. 1863 Harding B 11(3643)

[An Irish version based on the British broadsides]

e. "Drowsy Sleepers" a partial text in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society

D. [Early examples of first stanza of Drowsy Sleeper found in the US, showing its popularity]

a. "Wake Up," single stanza from the 1855 Social Harp by John G. McCurry of Georgia in 1852

b. "Awake awake" reported by George Dallas Mosgrove was born in Louisville, Kentucky c. 1864

c. "Wake Up" from the father of Mrs. Emma Kelly Davenport of Uvalde County, Texas; 1870.

E. [The Scottish versions of Drowsy Sleeper with a 2 stanza introduction and then similar to A and C; Roud No: 402]

a. "I Will Put my Ship in Order," from Traditional Ballad Airs, Volume 1, p. 225 by William Christie; 1876. Roud No: 406.

b. "I Drew My Ship into a Harbor" Northumbrian Minstrelsy: A Collection of the Ballads, Melodies, and Small-Pipe Tunes of Northumbria; edited by John Collingwood Bruce, John Stokoe; 1882.

c. "I Will Set My Fine Ship in Order." Sung by J. W. Spence of Rosecroft, Fyvie in April, 1906; Grieg-Duncan A

d. "I Will Set My Ship In Order." Sung by Mrs. Margaret Gillespie of Glasgow, Scotland, c. 1909. Grieg-Duncan C

e. "I Will Put My Good Ship In Order." Sung by Mrs. Sangster of Cortiecram, Mintlaw; c.1910, Grieg-Duncan B

f. "I Will Set My Good Ship in Order." Sung by Mr. Alexander M. Lee and Mrs. Lee of Stichen in June, 1908. Grieg-Duncan D

g. "I Will Set my Ship in Order" from John Ord's "Bothy Songs and Ballads," 1930.

F. [North American Drowsy Sleeper/Awake, Awake/Katie Dear versions; Roud No: 22621]

a. "The Drowsy Sleeper" sung by Mary Lou (Brown) Miller (AR) c1864 Haun

b. "Awake, Awake" from an MS by James Ashby (MO) 1874 Belden C

c. "The Drowsy Sleeper" sung by John Raese (WV) 1880 Cox A

d. "Who's at My Bedroom Window?"-- broadside by H. J. Wehman, Song Publisher, 50 Chatham St., New York; 1890.

e. "Willie and Mary" sung by Mr. A.S. White of Ontario. Learned from lumberjacks about 1900. from "Old Songs that men have sung" by Robert Gordon c. 1925.

f. "Drowsy Sleeper." Pettit, 1907. From: Ballads and Rhymes from Kentucky by G. L. Kittredge; JAF.

g. "Awake! Awake!" sung by Mary Sands of Madison Co., NC 1916 Sharp A. From English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians I.

h. "Who's That Knockin' On My Window" sung by The Carter Family, recorded June 8, 1938.

G. [The "composed ballad," one extant print version Gb was reprinted in 1849, 1850. Roud no. 711; Laws G21]

a. 'The Dying Lovers.' fragment from The Brown Collection Volume 2, 1952; taken from Miss Lizzie Lee Weaver of Piney Creek, Alleghany county, about 1915. The manuscript bears the notation "Written 1838."

b. "Silver Dagger" sung by Sal Jenkins; published in Spirit of the Times: A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature; New York City. Reprinted in 1849 in Gazette of the Union, Golden Rule and Odd-fellows' Family Companion, Volumes 10-11; 1849 Published: New York, N.Y.: J. Winchester.

c. "Young Men and Maidens" sung by S. G. Yoke of West Virginia, c1856 Cox C

d. "Come Youth and Age" Sung by William Larkin of Illinois, 1866 MS, Musick

H. ["Awake! Awake!" English traditional based on broadside text; Roud No: 22620.]

a. "Who is That That Raps at my Window? sung by Mr. Hills (Sussex) 1901 Merrick

b. "Awake! Awake!" sung by Amos Ash (Someret) 1905 Hammond

c. "Arise, Arise" sung primarily Susie Clarke as collected by Jack Barnard (Somerset) 1907, additional stanzas Lucy White; arranged Cecil Sharp.

d. "Who is There?" sung by Mrs. Marina Russell of Upway, Dorset in Jan./Feb. 1907. Collected by H. E. Hammond.

I. [Versions that include a stanza or several stanzas of the Drowsy Sleeper text]

a. "The Gold Ring" from Andros Island, Bahamas; Parsons 1918

b. "O Hatty Bell."- Sung by Mrs. Godfrey of Marion, NC on September 3, 1918 from Sharp MS

c. "O! Molly Dear Go Ask Your Mother" Kelly Harrell" recorded June 9, 1926 in New York City.

d. "Annie Girl" from Hudson, published in the JAF, 1926.

e. "Kind Miss" sung by Ann Riddell Anderson of the University of Kentucky from American Songbag by Carl Sandburg; 1927.

f. "Oh Molly Dear" sung by B.F. Shelton; recorded on July 29, 1927 in Bristol, Tennessee. Issued as Victor 4017.

g. "The False Lover" sung by Margaret Combs (KY) 1931 Henry

h. "Hattie Belle" MS from Greer Collection before 1932; hybrid version of "A Sweetheart in the Army"

i. "Vandy, Vandy"- a hybrid version from Manly Wade Wellman (1903-1986) of North Carolina- only the last stanza is from Drowsy Sleeper.

j. "Drowsy Sleeper." Sung by Hedy West from Alabama in 1963.

k. "Little Satchel" Sung by Fred Cockerham in 1966, recorded by John Cohen

J. [Irish versions related to and with stanzas from "The Grey Cock"]

a. "Sweet Bann Water"- collected by Sam Henry from Valentine Crawford collected in the Commercial Hotel, Bushmills in September 1937

b. The Cock Is Crowing- sung by John Butcher, 1969; collected by Hugh Shields.

c. "The Sweet Bann Water" sung by Joe Holmes and Len Graham; recorded 1977 by Séamus MacMathúna.

The theme of the night visit is of great antiquity[1]. In early related ballads the story is sometimes this: A young man goes to his lovers abode and he knocks on the window or door which wakes her. She asks who's there and opens the window (or door). He tries to gain entrance to see her. She warns him that her parents forbid him to come in and bids him to "go from the window." From Wedderburne's "The gude and godlie ballatis" dated 1567[2] comes perhaps the first related version which begins, "Who is a my window, who, who?":

"Quho is at my windo, qho, qho?

Goe from my windo, goe, goe!"

Quha callis there, so lyke ane stanger?

Goe from my windo, goe, goe!"

In the Stationers' Registers, B. fol. 226, a licensing of John Wolfe to print "A Ballade intituled Goe from the window goe." A 1610 play by John Fletcher[3] has "Come up to my window." Another early example of a "go from my window" song was sung by Merrythought in the 1613 play, The Knight of The Burning Pestle, by Beaumont and Fletcher:

"Go from my window, Love, go!

Go from my window, my dear!

The wind and the rain will drive you back again,

You cannot be lodged here.[4]

Here's an excerpt from The Secret Lover, an early black-letter broadside printed for P. Brooksby in West-Smithfield between 1672 and 1682. The excerpt begins with the second stanza which has additional phrases found in "Drowsy Sleeper:" The waking of his lover who asks "Who knocketh at the window?" The last line of each stanza uses a standard "night visit" chorus of "Go from the window, go!"

"What is my Love a-sleeping? or is my Love awake?"

"Who knocketh at the Window, who knocketh there so late?"

"It is your true love, Lady, that for your sake doth wait."

And sing, Go from the Window, love, go![5]

"Then open me your Father's Gate, and do not me deny;

But grant to me your true love, or surely I shall dye."

"I dare not open now the Gates, for fear my Father spy!"

And sing, Go from my Window, love, go!

"O Dearest, be not daunted, thou needest not to fear;

Thy Father may be sleeping, our loves he shall not hear:

Then open it without delay, my joy and only Dear!"

And sing, Go from the Window, love, go!

This last example of a related "night visit" ballad, which shows the daughter's fear of punishment by her parents, is titled John's Earnest Request, or, Betty's compassionate love extended to him in a time of distress. To a pleasant new tune much in request. It was printed for P. Brooksby, at the Golden Ball in Pye Corner; dated ca. 1730[6].

Come open the Door sweet Betty,

for its a cold winters night,

It rains, and it blows, and it thunders,

and the Moon it dos give no light

It is all for the love of sweet Betty,

that here I have lost my way;

Sweet let me lye behind thee,

untill it is break of Day.

I dare not come down sweet Johnny,

nor I dare not now let you in,

or fear of my Fathers anger,

and the rest of my other Kin:

For my Father he is awake,

and my Mother she will us hear;

Therefore be gone sweet Johnny,

my Joy and only Dear.

The "waking theme" stanza from the night visit is found similarly in several ballads of Child's 305 English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Here's the opening stanza of Earl Brand (No. 7):

Rise ye up, rise ye up, ye drowsy old cheerls,

Or are you all asleep?

Arise an' take keer of your oldest daughter dear,

For th' youngst I'll carry with me[7].

In Jamieson's version of "Clerk Saunders" (No. 69) the lover comes to his lady's bower and "tirls at the pin:"

"O sleep ye, wake ye, May Margaret,

Or are you the bower within?"

"O wha is that at my bower-door,

Sae well my name does ken?"

"It's I, Clerk Saunders, your true-love,

You'll open and lat me in[8]."

Other Child ballads[9] that have similar stanzas include "Willie's Fatal Visit" (No. 225), "Glasgerion" (Child No. 67), "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard" (Child No. 81), "Young Johnstone" (Child No. 88), "The Mother's Malison" (Child No. 216), and "Auld Matrons" (Child No. 249), Buchan's version of "Willie and Lady Maisry" (No. 70), and "The Bent sae Brown" (No. 71). One last example is the ballad "Young Benjie:"

"O open, open, my true-love,

O open, and let me in!"

"I dare na open young Benjie,

My three brothers are within.[10]" (Child No. 86A)

Similar to the preceding "night songs" is the fragment A, Song XCVII, "Awake, thou fairest thing in nature" as taken from Allan Ramsay's Tea-table Miscellany: A Collection of Choice Songs, Scots & English; Volume 2, dated 1725[11]. A, with similar wording captures the first two measures of the 1817 broadside, Ca, The Drowsy Sleeper[12]. Since it is short, I give A in its entirety here:

Song XCVII.

He

Awake, thou fairest thing in nature

How can you sleep when day does break?

How can you sleep, my charming creature,

When half a world for you are awake[13].

She

What swain is this that sings so early,

Under my window by the dawn?

He

'Tis one, dear nymph, that loves you dearly,

Therefore in pity ease my pain.

She.

Softly, else you'll 'wake my mother,

No tales of love she lets me hear;

Go tell your passion to some other,

Or whisper softly in my ear.

He.

How can you bid me love another,

Or rob me of your beauteous charms?

'Tis time you were wean'd from your mother,

You're fitter for a lover's arms.

All four stanzas of Ramsay's song have been found in tradition. The last line of the third stanza should appear, "And whisper in her ear," or similarly. After all she's asking him to go tell his passion to another and whisper in her ear.

Ba, a ballad recreation by Allan Cunningham (1784-1842) titled, "O Who is this Under My Window?" was published in December, 1810 in Cromek's "Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song, with Historical and Traditional Notices relative to the Manners and Customs of the Peasantry." The ballad was attributed to Martha Crosbie. Cunningham's recreation was based on a traditional ballad, Bb, of which 5 stanzas and a brief synopsis were published by Cunningham in 1834[14].

In the summer of 1808, just after after publishing a book about Robert Burns[15], R. H. Cromek came to Dumfriesshire with the artist Stothard to collect material "for an enlarged and illustrated edition of the works of Burns[16]." The famous Scottish poet Robert Burns, who died in 1796 in Dumfries, for a short time (1788-1790) leased a farm in Ellisland and was a neighbor of Allan and his father, John Cunningham (1743-1800). Later in life, Allan claimed to remember hearing Burns recite "Tam o' Shanter" to his father in 1790[17] when he was just six years old.

Cromek was also preparing for publication a "Collection of Scottish Songs, with notes and memoranda of Burns[18]." Through a letter of introduction, Cromek met Allan Cunningham and the two men's talk was "all about Burns, the old Border Ballads, and the Jacobite songs of '15 and '45[19]." After Cromek suggested publishing a volume of traditional songs from the peasants of Nithsdale, Cunningham went about collecting traditional songs and ballads in Nithsdale and Galloway. Cunningham, like Burns and others (Hogg mentions Motherwell) submitted folk songs for publication which he had recreated. Cromek returned to London and had no knowledge that the songs sent to him were recreations and also original poetry written in the style of the Scottish balladeer. In order to finish "Remains" in early 1810 Cromek requested Cunningham move to London, which he did on April 9, 1810. "Remains" was published later in the year, in December of 1810[20].

Cunningham's notes for the song "O Who Is This Under My Window?" follow[21]:

This old song is taken down from the singing of Martha Crosbie, from whose recitation Burns wrote down the song of "The Waukrife Minnie."

It has a fine affecting tune, and is much sung by the young girls of Nithsdale. Burns has certainly imitated the last verse of it in his "Red, Red Rose."

From the notes, if they are to be believed, Martha Crosbie would have been an informant for Burns during his stay at Ellisland farm, from 1788-1791 (or perhaps later when he moved to Dumfries but it was certainly before 1796) and since she entertained the Cunningham children, Burns would likely have met her through John Cunningham, Allan's father. Cunningham would have known the ballad by 1809 when he sent Ba to Cromek in London, having learned it from Crosbie at his father's house. Either he wrote the original down or had an excellent memory, because 24 years later he published Crosbie's traditional original as the notes for Burns', "A Red, Red Rose."

Here is the original from 1834 given in full, the Poet mentioned in the first line is of course Robert Burns[22]:

'An old Nithsdale song seems to have been in the Poet's thoughts when he wrote this exquisite lyric. Martha Crosbie, a carder and spinner of wool, sometimes desiring to be more than commonly acceptable to the children of my father's house, made her way to their hearts by singing the following ancient strain:-

"Who is this under my window?

Who is this that troubles me?"

"O, it is I, love, and none but I, love,

I wish to speak one word with thee.

Go to your mother, and ask her, jewel,

If she'll consent you my bride to be;

And, if she does na, come back and tell me,

This is the last time I'll visit thee."

"My mother's in her chamber, jewel,

And of lover's talking will not hear;

Therefore you may go and court another,

And whisper softly in her ear."

The song proceeds to relate how mother and father were averse to the lover's suit, and that, exasperated by their scorn, and the coldness of the maiden, he ran off in despair: on relenting, she finds he is gone, and breaks out in these fine lines:-

"O, where's he gone that I love best,

And has left me here to sigh and moan?

O I will search the wide world over,

Till my true love I find again.

The seas shall dry, and the fishes fly,

And the rocks shall melt down wi' the sun;

The labouring man shall forget his labour,

The blackbird shall not sing, but mourn,

If ever I prove false to my love,

Till once I see if he return."

In "A Red Red Rose," which Burns took almost wholly from tradition, he quotes the first two lines of Crosbie's last stanza[23]. This quote appears similarly in a blackletter broadside, The Sailor's Departure from His Dearest Love and is standard in the Scottish "I Will Put My Ship" versions.

The recreation by Allan Cunningham of Crosbie's version that was sent to Cromek in 1809 begins[24]:

O Who is this under my window?

O who is this that troubles me?"

"O it is ane wha is broken-hearted,

Complaining to his God o' thee."

"O ask your heart, my bonnie Mary,

O ask your heart gif it minds o' me!"

"Ye were a drap o' the dearest bluid in't,

Sae lang as ye were true to me."

Not much can be salvaged from Cunningham's recreation except the seventh stanza which proceeds the last two stanzas of Crosbie's original:

O up she rose, and away she goes,

Into her true love's arms to fa';

But ere the bolts and the bars she loosed,

Her true love was fled awa.

From the many[25] collected Scottish versions of the ballad come this standard text[26]:

Up she rose put on her clothes,

It was to let her true love in,

But ere she had the door unlocked

His ship was sailing on the main.

It seems likely that Cunningham reworked line 2 and 4 of this stanza but not to such a degree that they could perhaps be traditional. The importance of Cunningham's recreation lies only in establishing an early date for the complete ballad, since Ramsay's song is but four stanzas. The date 1809 can be given with certainty since that is the date the ballad was sent to Cromek in London. What appears likely, albeit with some speculation, is the date could coincide with the date Burns collected "The Waukrife Minnie" from Crosbie--circa 1788, when Burns moved to his Ellisland farm.

It's a pity that Cunningham didn't write out the the four traditional stanzas where the parents are asked their permission for the lovers to wed. This would provide the reason that he departed never to return. In the other Scotch versions it's the dispraise from a letter. Cunningham's sublime poetry can not match the "vulgar" words of the peasantry and obscures one of the few "reliques" of this ballad's heritage.

Another reworking of the traditional ballad is found in the English broadside, The Drowsy Sleeper, my C. Ramsay's song, A, has two stanzas found in the opening of The Drowsy Sleeper, version Ca, a broadside taken from the Bodleian Library as published by J. Crome of Sheffield; c. 1817. The ballad is the work of a broadside writer and only the first two stanzas are traditional. Subsequent broadsides[27] include Cb as published by J. Pitts of London c. 1820; Cc, titled "Maiden's Complaint" by T. Birt, London c. 1828 and Cd, "Awake Drowsy Sleeper," by H. Such of London c. 1865. After the first two traditional stanzas of Ca, found similarly in A, the father wakes and goes to the window but his daughter's lover Jemmy has gone. His daughter implores Jemmy to return saying she will marry him. Her father tells her he will confine her and that Jemmy will go to the sea. She asks for her portion, five thousand pounds, so she may follow him across the ocean. Her father declines and says he will confine her and give her bread and water once a day. She replies that she will die a single girl if she can't have her love.

Broadside Ba, 1817 printed by J. Crome, Sheffield

In Cc the father overhears them and sends Jemmy into military service (press gang) overseas. She may write her love a letter but is confined and vows to die a single girl. In the Firth broadside, C.17(25), Cd: she says she will go to Botany Bay to be with Jim and asks for her portion of five hundred pounds; her father denies her portion but says "you and your true love shall be married, And that will ease you of all your pain." Traditional versions from the UK that used the broadside texts Ca-d were collected in the early 1900s and are found under H. The British broadsides (C) and traditional versions based on the broadsides (H) usually only present the first two stanzas[28] of the cumulative traditional ballad as found in Scotland (B, E), Ireland (J) and North America (F). A "letter" is mentioned in the broadsides but it is not an integral part of the plot as in E.

The traditional ballad and especially the opening stanza was widely known in North America[29] by the mid-1800s. D, is a variant of the first stanza of C was first printed in the US in the 1855 Social Harp, a religious shape-note book with some secular songs, by John McCurry of Georgia. Here's the text titled "Wake Up" as by John G. McCurry of Georgia in 1852:

Wake up, wake up, ye drowsy sleepers,

O wake, O wake for it's almost day!

How can you lie there and sleep and slumber,

When your true love is going away?

The opening stanza was reported in "A Legacy of Words: Texas Women's Stories, 1850-1920" p. 85 by Ava E. Mills as taken from Mrs. Emma Kelly Davenport of Uvalde County, Texas who recalled her father singing the ballad in 1870 before leaving for California[30]:

They bought up different small herds around in the country and got together about 3,000 head. John Davenport (whom I was later to marry) and others of the neighborhood stayed up at the ranch headquarters the night before the herd left on the trail. They went with the outfit for one day's travel. The last night we stayed at home, which was this same night the boys were all camped around to start before day the next morning. The camp was awakened by my father singing that old song:

Wake up, wake up, you drowsy sleepers

Wake up, wake up, it's almost day!

How can you lie and sleep and slumber

When your true love is going away!'

George Dallas Mosgrove was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1844, and enlisted in the Fourth Kentucky Cavalry Regiment as a private on September 10, 1862. In his book, Kentucky Cavaliers in Dixie; or, The Reminiscences of a Confederate Cavalryman (271 pp., Courier-Journal Job Printing Co., Louisville, 1895) he describes a Kentucky soldier who sang the ballad during the Civil War to rouse the Fourth Kentucky boys[31]:

"Possessing a deep bass voice, he was wont to arouse the Fourth Kentucky boys by singing, 'Awake, awake, ye drowsy sleeper,' in the early morn before Tom Hayden sounded reveille with his bugle."

It's likely the ballad came to the North America long before the first printed broadsides in England in 1817[32]. In North American the opening stanza or stanzas were kept but the conflict with the parents changed. These ballads are found under F. In most full versions both the mother and father are asked by the daughter if the lovers can marry and both reject the marriage proposal. Usually the father has a weapon, or silver dagger, to slay the one she loves. Since the lovers are unable to marry, one or usually both commit suicide with the silver dagger. This traditional version was first printed in the US by Wehman in NY, my Fd, in 1890[33].

Over one hundred and fifty North American traditional versions of the ballad[34] have been collected under a variety of names including: "Willie and Mary," "Awake Awake," Who is Knock at my Window?" "Bedroom Window," "Katie Dear," "Wake Up, you Drowsy Sleeper," "Oh Molly Dear" and "Silver Dagger." The ballad was also recorded in the 1920s as an early country ballad[35]. It has remained popular and has been widely recorded in recent years[36].

From this traditional North American version of the Drowsy Sleeper that was widely circulated in the early 1800s came an eleven stanza "composed" version of the ballad that had different opening stanzas which began: "Young men and maidens lend attention." This composed ballad usually titled "The Silver Dagger," G, was probably printed in a "dime book," songster, or as a broadside in the early 1800s. One print version (my Gb) attributed to an informant, Sal Jenkins of Indiana, was reprinted in a publication[37] from NY in 1849. The article was first printed in the N.Y. "Spirit of the Times" (also in 1849), a weekly NY gazette and the article was reprinted again in early 1850 in a Vermont newspaper. Here are the first three of her eleven stanzas:

The Silver Dagger

Young men and maidens pray lend attention,

To these few lines I am about to write:

It is as true as ever was mentioned

Concerning a fair beauty bright.

A young man courted her to be his darling

He loved her as he loved his life,

And often times to her he vowed

That he would make her his lawful wife.

But when his father came to know it,

He strove to part them night and day;

To part him from his own dear jewel

She is poor, she is poor, he did oft-times say.

This composed version uses the double-suicide theme of the traditional versions plus stanza 7 and half of stanza 11. It is considered a different song. I am including the ballad here under Drowsy Sleeper, noting that it is a composed ballad on the same theme as the traditional North American versions. According to Belden the "composed Silver Dagger" ending has also been combined with the traditional Drowsy Sleeper[36]:

"Altho from its style and content this seems clearly to be a product of the professional ballad-maker, I know of no ballad print of it either British or American (except No.518 in 'Wehman's series of ballad prints, where it is combined with The Drowsy Sleeper); it is recorded only from traditional singing, and that only from the South and the West. That its conclusion has been incorporated in texts of Bedroom Window has already been noted."

Belden never saw the three printed versions from NY attributed to Sal Jenkins. Kittredge, who published a version of the composed ballad in 1907[39], had nothing to say about the composed ballad at that time since it was new to him. Then in 1917 he writes "the conclusion of versions IV and V (below) shows admixture of 'The Silver Dagger'[40]." Kittredge's failure to identify the ballad as "composed, using stanzas from the traditional ballad" and Belden's 1940 statement are the source of much of the confusion concerning the two popular American versions. Although Belden correctly identifies the composed ballad (The Silver Dagger) as being made by a "professional ballad-maker" or print-writer he concludes incorrectly that "its conclusion has been incorporated in texts of Bedroom Window." Instead, his summary should be, "the ballad maker has incorporated stanzas from the end of Bedroom Window." How do we know that the traditional ballad was used as a basis for the composed ballad? Here are two reasons:

1) The broadside writer or professional ballad maker historically uses existing ballads to create new ones. For example upon the theme of my ballad No. 3, the Bramble Briar, George Brown, a prolific writer for the London trade, wrote "Merchant's Daughter, or Constant Farmer's Son." The composed ballad, "The Constant Farmer's Son," has long been understood as being based on "The Bramble Briar. Even the broadside, The Drowsy Sleeper" was created from from several stanzas of an earlier traditional ballad which was partially printed by Ramsay in Volume 2 of his Tea-Table Miscellany in 1725. The 1817 Drowsy Sleeper broadside (Ca) itself is mainly a literary creation and only the first two stanzas are traditional. The source of the broadside is unknown but it could be John Crome, the printer.

2) By logical reasoning, traditional singers would not have taken only a single stanza from the conclusion (the Silver Dagger stanza) without taking other stanzas. Other stanzas from the composed ballad (usually titled, The Silver Dagger) are not found in the traditional one[41]. The same is true of the traditional ballad-- other stanzas from the composed ballad are not found in the traditional ballad.

Clearly these are two distinct ballads and have remained so during oral transmission. Here's the likely scenario for the composed ballads creation. Using the double-suicide as the theme the writer created an alternate reason for rejection of the lovers by the parents: "she was too poor." This weak hypothesis (since the male is seen as the provider in the early 1800s) causes the parents to try and separate the lovers. The girl realizing they could never be together without his parents approval decides to end her life. At this point the print writer used a traditional stanza as the basis for stanza 7:

Then out she pulled her silver dagger.

And pierced it through her snow white breast;

At first she reeled, and then she staggered,

Saying, oh! my dear, I’m going to rest. [1849 print version]

The printed writer also added a rhyme not found in tradition between 1 and 3 dagger/stagger[ed]. The text of the composed ballad appears similarly in stanza 9 when the male lover stabs himself. The composed ballad simply used one and a half stanzas from the traditional ballad otherwise they are distinctly different.

From stanza 7 and 9 the composed ballad became titled, The Silver Dagger. Because both the traditional North American versions and the composed ones have "silver dagger" in the text and have been titled "Silver Dagger[42]," naturally many collectors and researchers have been confused about how to classify each version[43]. Belden, Cox, and Sharp[44], for example, had no problem-- they simply separated the composed version and called it, "The Silver Dagger." The traditional version was called "Awake Awake" by Sharp, "Drowsy Sleeper" by Cox and Belden titled his "The Bedroom Window (The Drowsy Sleeper)." In North America there's simply a "traditional version" and a "composed version"-- both usually have the "silver dagger" in the text (or "weapon" or "dagger").

* * * *

A different UK version of the ballad, Ea, from Scotland, "I Will Put my Ship in Order," [Roud 402] was taken by William Christie from his maternal grandfather and published in 1887[45]. This version still has the "night visit" stanzas (similar to the broadsides) which are followed by the "permission of the parents to marry" stanzas similar to those in the North America and B from Cunningham. A variant, Eb "I Drew My Ship into a Harbour" was collected by Stokoe and published in Northumbrian Minstrelsy: A Collection of the Ballads, Melodies, and Small-Pipe Tunes of Northumbria; edited by John Collingwood Bruce, John Stokoe; 1882. Versions of "I will Put my Ship" were widely collected in North Scotland in early 1900s by Gavin Greig (1856–1914), and the minister James Bruce Duncan (1848-1917). Twenty-two versions (A-V) were published in the Grieg-Duncan Collection, Volume Four, of which I've selected 4 representative versions Ec-Ef. Eg was collected by John Ord in the early 1900s[46]. "I Will Put My Ship" has an introductory double stanza before that standard broadside opening:

I will put my Ship in order.

"Oh, I will put my ship in order,

And I will set her to the sea;

And I will sail to yonder harbour,

To see if my love will marry me."

He sailed eastward, he sailed westward,

He sailed far, far by sea and land;

By France and Flanders, Spain and Dover,

He sail'd the world all round and round[47];

This is followed by a variant of the two standard opening stanzas the ballad. The middle section is similar to the traditional North American versions where the lover asks the daughter to get permission to be married from the mother and then the father (4 stanzas). The father, rather that a dagger, has in his hand a letter "to the dispraise" of her lover. The lover responds that he has been nothing but a loyal, trustworthy lover. When the daughter dresses and goes to the door to let her lover in, she finds he has gone and is back sailing the main. The daughter cries after him, "Come back" she will marry him but it is of no use. He responds in the last stanza[48]:

The fish may fly, love, the seas go dry, love

The rocks may moulder and weep the sand,

And husbandmen may forget their labour

So keep your love, until I return. [Greig-Duncan G]

This stanza is similar to those at the end of the 1834 version given by Cunningham and are part of the "True-Lovers Farewell" family of songs traced back to the broadside "The Unkind Parents, or, The Languishing Lamentation of two Loyal Lovers[49]". This first part of the ending and some similar stanzas are found in another night-visit ballad, The Lover's Ghost (Child 248). Sometimes there is an ending stanza where she jumps in the sea and drowns:

She turned herself right 'round about then,

And plunged her body into the sea,

It's fare ye well my true love Johnny,

Ye needna more come visit me[50].

A composite of 16 stanzas was created by Steve Gardham from the 21 versions collected by Greig/Duncan, the version by Christie from 1876 and the 1930 version by Ord. See the headnotes of "British & and other Ballads" to view the entire composite.

An Irish variant, titled "Sweet Bann Water," my J, is based on another night-visit ballad, "The Lover's Ghost[51]," which is part of the Child 248 family. "Sweet Bann Water" was collected by Sam Henry in Antrim during 1937. Two other traditional variants of "Sweet Bann Water" have recently appeared in Ireland. "The Cock Is Crowing" was sung by John Butcher, and collected in 1969 by Hugh Shields. A stanza of "The Sweet Bann Water" as sung by Joe Holmes and Len Graham was recorded in 1977 by Séamus MacMathúna. The complete version has been recorded several times by Len Graham and has a stanza found occasionally in versions from the US southwest[52]. Cover versions of "Sweet Bann Water" have been recently recorded.

There are now six distinct ballad-types that fall under the Drowsy Sleeper heading:

1. The British broadsides (B), the earliest, Ba, dated circa 1817 is named Drowsy Sleeper. This includes UK traditional versions based on the broadsides (H). The lovers do not seek the parents permission to marry and therefore no the dagger is present. A letter is mentioned but it is not and integral part of the ballad story. Roud No: 22620

2. "I Will Set My Ship" versions from Scotland (E), the first from Christie. Greig/Duncan collected twenty-two variants. Roud No: 402. The Ramsay fragment and the incomplete Nithsdale version given by Cunningham in 1834 should also be included here. I am uncomfortable giving Cunningham's ballad any authority (such as heading this ballad type) without further corroboration.

3. Traditional versions of Drowsy Sleeper from North America (D and F); Roud No: 22621. They usually mention a weapon or silver dagger held by one or both of the parents. Theses versions usually have the suicide or double suicide of the lovers.

4. Versions from the US or rarely Canada, Roud No: 711, that are based on an early missing print version or "composed " ballad that begins: "Young men and maidens lend attention." These versions are usually titled "Silver Dagger" or the title comes from the first line "Young Men and Maidens." Also titled "Parent's Warning" or Bloody Warning" or similarly. Most collectors (Belden; Sharp; Cox; Brown) categorize them separately under "Silver Dagger."

5. Versions from North America and the Bahamas that have become mixed with other songs. The most common added songs are from "East Virginia Blues/Old Virginny." One hybrid type (four versions) is a mixture of three songs usually ending with stanzas from "The Broken Token/Sweetheart in the Army" songs.

6. Irish versions (Sweet Bann Water) that are related to or derived from Costello's "The Grey Cock" and other related songs such as "Rise Up Quickly and Let Me In" (also called The Ghostly Lover). Songs titled "Lover's Ghost" which similarly have the night visit at the window but no "permission from the parents" stanzas are not included.

Stanzas from the "True Lovers Farewell" family of songs were added to the end of some North American "Drowsy Sleeper" versions as found in the 1834 Cunningham version and the 1876 Scottish "I Will Put My Ship In Order:"

6. I'll go down in some lone valley,

And spend my weeks, my months, my many years,

And I'll eat nothing but green willow,

And I'll drink nothing but my tears[53]. [Sharp A, 1916]

5 The sea's so wide I cannot wade it,

Nor neither have I wings to fly;

I wish I had feet like a sparrow

And wings like a little dove,

I'd fly away off from the hills of sorrow

And light on some low lands of love[54]. [Sharp F, 1918]

These ending occur in North American version where the lovers do not commit suicide which is yet another category. Other North American versions (for example B. F. Shelton's "Oh Molly Dear") are made up mostly of stanzas from different songs. These songs include “In Old Virginny,” “Man of Constant Sorrow,” “East Virginia Blues,” “Dark Hollow,” and “Darling, Think of What You’ve Done.” A good example given in its entirety follows:

OH MOLLY DEAR

Oh once I lived in old Virginny

To North Carolina I did go

There I saw a nice young lady

Oh her name I did not know

Her hair was black and her eyes was sparkling

On her cheeks were diamonds red

And on her breast she wore a lily

To mourn the tears that I have shed.

Oh when I'm asleep I dream about her

When I'm awake I see no rest

Every moment seems like an hour

Oh the pains that cross my breast.

Oh Molly dear, go ask your mother

If you my bride can ever be

If she says no, come back and tell me

And never more will I trouble thee

Last night as I laid on my pillow

Last night as I laid on my bed

Last night as I laid on my pillow

I dreamed that fair, young lady was dead

No, I won't go ask my mother

She's lying on her bed of rest

And in one hand she holds a dagger

To kill the man that I love best

Now, go and leave me if you want to

Then from me you will be free

For in your heart you love another

And in my grave I'd rather be[55].

Following is a list of early county recordings[56]. Both Harrell and Shelton's are hybrid versions:

1) Oh Molly Dear (BVE 35667-3)- Kelly Harrell- 6-09-1926

2) Oh Molly Dear (BVE 39725-2)- B. F. Shelton- 7-27-1927

3) Sleepy Desert (Paramount 3282, 1931; on TimesAint03)- Wilmer Watts & the Lonely Eagles- 1929

4) Wake Up You Drowsy Sleeper (BE 62575-2)- Oaks Family- 6-04- 1930

5) Katie Dear (14524-2) - Callahan Brothers (vcl duet w.gtrs) - 01/03/1934. NYC.

6) Katie Dear (BS 018680-1) - Blue Sky Boys (vcl duet w/mdln & gtr) - 01/25/1938. Charlotte, N.C. (Bill and Earl Bolick) Within The Circle/Who Wouldn't Be Lonely, BSR CD 1003/4.

7) Katy Dear (64077-) - Tiny Dodson's Circle-B Boys (vcl w/vln & gtrs) - 06/07/1938.

The Drowsy Sleeper and its variants are somewhat rare in New England and Canada. Since the composed version ("Silver Dagger"/ "Young men and maidens lend attention") was published in Hew England at least three times around 1850 it's surprising that it has not been found in greater numbers there[57]. The Vermont version and one from Ontario use "shining dagger" and Northern versions may be identified by "shining" instead of "silver."

* * * *

One of the important details is a letter usually held by the father and sometimes the mother. The content of the letter is clear in the British broadsides and Scottish variants but less clear in versions from North America. In the British broadsides the father has her lover enlisted into the military where he is taken overseas. The father suggests the daughter write him a letter:

"O daughter, daughter, I will confine you.

Jemmy he shall go to sea,

And you may write your truelove a letter,

As he may read it when far away.[58]"

However, a second instance concerning a letter is found in "I Will Put my Ship" variants. The second instance is corrupted in the US and I have found only two versions where a letter is held by a parent that tells of the lover's dispraise or disgrace:

Oh, no I’ll not go ask my mother,

For she lies on her bed at rest,

And in her hand she holds a letter,

That tells you of your own disgrace. [Oleavia Houser Fayetteville, Arkansas 1958]

Here are the two writing letter stanzas (10 and 11) from "I Will Set My Ship-in Order" sung by James Duncan's sister[59] and the result:

10. My father's in his office writing,

Settling up his merchandise;

In his right hand he holds a letter,

And it speaks greatly to your dispraise.

11. To my dispraise, that is not true love,

To my dishonour, that cannot be,

For I never slighted you nor yet disowned you,

Until this night you've slighted me.

12 If ye be Johnie, my true love Johnie,

I will rise an' let you in,

But e'er she got unto the window

He was bound for his ship again.

In the above stanzas her father has a letter that speaks to Johnnie's "dispraise." He replies that he's done nothing. By the time she dresses to let him in, he's bound for his ship again. I believe that the letter is the final insult and Johnny must be away!

* * * *

The ballad was also known by African Americans. In 1928 Newman Ivey White reported a fragment from the African-American community in his American Negro Folk-Songs, p. 178):

Mary Bell, Go ask yo' mama,

If you an' I be bride alone;

If she say no, come back an' tell me

An' Mary Bell will run away

Bayard who supplied two stanzas from Pennsylvania, comments that the melody of the North American traditional version belongs to the Butcher Boy/Lord Bateman family of songs.

And a cajun version titled, "Dans mon Chamis Rencontre," was collected by Alan Lomax in 1934 and appears in Traditional Music in Coastal Louisiana: The 1934 Lomax Recordings by Joshua Clegg Caffery.

* * * *

Conclusion:

The traditional ballad was developed from the early English "night-visit" songs; an estimated date would be in the mid-1600s. In 1725 Ramsay published a four stanza fragment, Song XCVII, in his Tea-table Miscellany: A Collection of Choice Songs, Scots & English; Volume 2. By the late 1700s stanzas where the lovers ask the girl's parents permission to be married were added. The full ballad was brought to North America by the end of the 1700s with a new twist-- the father had a silver dagger to slay the one his daughter loved the best. The result of the parent's refusal and the silver dagger was Type 1) the daughter's lover leaves to live alone to eat nothing but sorrow and drink nothing but tears, or Type 2) the daughter's lover kills himself with the silver dagger and then she kills herself[60]. A composed ballad, usually titled "The Silver Dagger" was written by 1820 in the US on the theme of the double suicide which borrowed one stanza from the traditional ballad. It begins similarly, "Come men and maids. . ." During the late 1700s or by 1809, Alan Cunningham collected "O Who is This at my Window" from Martha Crosbie who sang the ballad at his father's house in Ellisland, Scotland. Cunningham rewrote her ballad and sent it to Cromek in London where it was published in "Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song" in 1810. In 1834 Cunningham published Crosbie's traditional Scot version in one of his books, Works of Robert Burns: With His Life, Volume 4. In 1817 a broadside writer took part of the plot and first two stanzas of the traditional ballad and composed nine more stanzas to create "The Drowsy Sleeper." By the mid-1800s a variant of Crosbie's Scottish traditional ballad titled "I Will Put My Ship in Order" was being sung in Northern Scotland. A text similar to the Scottish traditional text was wed to another night-visit song, "The Lover's Ghost" and became an Irish variant titled, "Sweet Bann Water," was collected by Sam Henry in 1937. This Irish variant was collected twice in Ireland in 1960s and 70s. Textual phrases, lines and stanzas of the UK ballads have been found in North America but no version with Silver dagger or weapon has been found in the UK.

R. Matteson 2016]

------------------

Footnotes:

1. Here are other ancient examples of night songs (the Germans call them, fensterlieder, or window songs). In Chaucer's Miller's Tale we find the "Go from my window" theme:

"Go fro the wyndow, Jakke fool," she sayde;

"As help me God, it wol nat be 'com pa me

In a sonnet by Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586) Eleventh Song of Astrophil and Stella we find:

"Who is it that this darke night,

Underneath my window playneth?"

"It is one who from thy sight

Being, ah, exil'd, disdaineth

Every other vulgar light."

The balcony scene in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet is another example of the male lover secretly visiting his amour. Her response to his "knock":

What man art thou that thus bescreen'd in night

So stumblest on my counsel? (II. ii. 52-3)

Norm Cohen, McNell and others have mentioned the ancient custom of authorized night visits by a young man who comes to court a young woman at her home. They are called "bundling (US/UK)" or "fenstern (Germany)," "Kiltang (Switzerland) and "queesting (Netherlands)." Since the parents and the daughter do not know the young man is visiting, these "night visits" are not authorized by the parents and therefore the authorized visits have nothing to do with the Drowsy Sleeper songs.

For a detailed exploration of the "night visit" songs see Charles Read Baskervill's article, English Songs on the Night Visit (PMLA, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Dec., 1921), pp. 565-614), which is attached to the Recordings & Info page. See also the related Harley 2253 version titled "De clerico et puella." [British Library MS Harley 2253 is a unique fourteenth-century miscellany consisting of 140 folios]

2. A compendious book of godly and spiritual songs commonly known as 'The gude and godlie ballatis': reprinted from the edition of 1567 by Wedderburn, John, 1500?-1556; Wedderburn, James, 1495?-1553 and Wedderburn, Robert, ca. 1510-1557.

3. From Fletcher's well-known play, Monsieur Thomas (c. 1610):

Thomas. I am here Love, tell me deere Love,

How I may obtaine thy sight.

Maid. Come up to my window love, come, come, come,

Come to my window my deere,

The winde, nor the raine, shall trouble thee againe,

But thou shalt be lodged here. (III. iii. 66-93)

4. The Knight of the Burning Pestle by Beaumont, Francis (1584-1616) and Fletcher, John (1579-1625) was first performed in 1607 and was alter published in quarto in 1613. It was included in folios published in 1635 and 1679.

5. This is the second stanza of The Secret Lover, printed for P. Brooksby in West-Smithfield between 1672 and 1682.

6. The full ballad is available online at Google Books.

7. From Randolph, Ozark Folksongs I, 1946. Sung by Mrs Stephens of Missouri in 1928, dating back through her family to circa 1828.

8. From Francis James Child's English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume 3, 1885.

9. I will not give examples of the following ballads found in Francis James Child's English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ten volumes 1882-1898.

10. From The English and Scottish Popular Ballads; Volume 4: Ballads 83-113, published December, 1886.

11. According to Roxburghe Ballads (6th volume, part 2) Volume 2 was published in 1725 (Ebsworth). Another source, Jim Brown, gives 1727.

12. I will give two examples but all the Ramsay stanzas scan to Drowsy Sleeper (with different wording):

Ba. The Drowsy Sleeper- Harding B 28(233) J. Crome; c. 1817

"Awake, awake, ye drowsy sleeper.

Awake, awake! 'Tis almost day.

How can you sleep, my charming creature,

Since you have stole my heart away?"

Ramsay:

Awake, thou fairest thing in nature

How can you sleep when day does break?

How can you sleep, my charming creature,

When half a world for you are awake.

Who's That Knocking on My Window?- Carter Family- June 8, 1938;

I've come to wean you of your mother

Pray trust yourself in your darling's arms!

and compare to these lines from Ramsay's Tea-Table Miscellany, c. 1725

'Tis time you were wean'd from your mother,

You're fitter for a lover's arms.

13. The last line of the first stanza is unique as far as I know.

14. Cunningham's recollection appears in his Works of Robert Burns: With His Life, Volume 4 (1834). Although Cunningham is not a reliable source, in this case the ballad given is clearly from tradition. Unless it was written down, it is however a recollection of a song sung 25 years earlier.

15. Reliques of Robert Burns, consisting chiefly of original Letters, Poems, and Critical Observations on Scottish Songs. Collected and published by R. H. Cromek. 8vo. pp. 453. London, Cadell and Davies, 1808.

16. Life of Allan Cunningham: With Selections from His Works and Correspondence by David Hogg, 1875.

17. The Burns Encyclopedia; online.

18. Life of Allan Cunningham: With Selections from His Works and Correspondence by David Hogg, 1875.

19. Ibid

20. Ibid.

21. Published in Cromek's "Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song, with Historical and Traditional Notices relative to the Manners and Customs of the Peasantry," 1810.

22. Cunningham's Works of Robert Burns: With His Life, Volume 4 (1834).

23. The following bold lettering in stanzas 2-4 show some of the borrowing Burns made in his famous short song:

II. As fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

So deep in luve am I :

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

’Till a’ the seas gang dry.

III. ’Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi’ the sun:

I will luve thee still; my dear,

While the sands 0’ life shall run.

IV. And fare thee weel, my only luve!

And fare thee weel a-while!

And I will come again, my luve,

Tho’ it were ten thousand mile. [This last stanza is similar to the first stanza of "The Unkind Parents, or, The Languishing Lamentation of two Loyal Lovers" 1690

1. Now fare thou well my Dearest Dear,

And fare thou well a while,

Altho' I go, I'll come again;

If I go ten thousand mile, Dear Love,

If I go ten thousand mile.]

24. From Cromek's "Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song, with Historical and Traditional Notices relative to the Manners and Customs of the Peasantry," 1810.

25. There are 22 Scottish versions (A-V) of "I Will Put/Set my Ship in Order" in the Grieg Duncan collection; "I Will Put my Ship in Order," the Christie version and the variant "I Drew My Ship into a Harbor" from John Collingwood Bruce and John Stokoe; 1882. A total of 24 extant versions.

26. Grieg-Duncan C; "I Will Set My Ship In Order" as sung by Mrs. Margaret Gillespie of Glasgow, Scotland, c. 1909.

27. Ca-Cd represent the known extant broadside types which have slightly different texts. Another title is "The Cruel Father or The Maiden's Complaint" for the text of Cb. I've examined three other broadsides with ostensibly identical texts.

28. Ca only has two stanzas with the cumulative traditional ballad but Cd could arguably have four. Ca, as the oldest broadside, is the title holder of this ballad family and the main representative of the broadsides.

29. This is the standard response found in the broadsides (C) and the English traditional versions (H), as well as in many version from North America.

30. From "A Legacy of Words: Texas Women's Stories, 1850-1920" p. 85 by Ava E. Mills as taken from Mrs. Emma (Emily) Kelly Davenport of Uvalde County, Texas. The original typed MS can be viewed at the LOC.

31. Additional text from Mosgrove is not given. The unnamed bass singer subsequently died in the next battle.

32. The extensive dissemination in remote areas in North America leads me to believe that the traditional versions, F, were brought to America by the late 1700s. The point of origin for this ballad in Appalachia was The Virginia Colony. The three versions Sharp collected in Madison County from Mary [Bullman] Sands in 1916 Anelize Chandler [Anna Eliz(abeth) Chandley] in 1916 and later Alex Coffey were likely brought to that region by members of the Roderick Shelton family who came from Virginia to Madison County around the late 1700s. Members of the Hicks family also knew the ballad. It's possible it was brought to the region by David Hicks or his son 'Big Sammy" Hicks during the Revolutionary period. G, the "composed ballad" was probably printed by 1820 in the Northeast US and had spread to the Appalachians before the Civil War. Since G is not represented in the UK it's unlikely the UK was the source.

33. "Who s at My Bedroom Window?" is a broadside by H. J. Wehman, Song Publisher, 50 Chatham St., New York; 1890. This is a traditional version probably acquired by the printer from a New York informant. "Katie" is a popular name for the lover and was collected and recorded many times under that title.

34. The exact number has not yet been determined. There are currently 115 traditional versions-- if you add versions in collections but not written out (15) and missing versions (30); there are over 160 versions.

35. See a list of recording given by Guthrie Meade further down the page.

36. Recent popular recordings of Katy Dear/Silver Dagger (not the composed version) include Joan Baez- 1960, Old Crow Medicine Show and Dolly Parton. I Drew My Ship Into the Harbour /I Will Put My Ship in Order was covered by Shirley Collins, Colin Tucker, Eliza Carthy, Capercaillie, and June Tabor. Sweet Bann Water has recently been recorded by Andy Irvine and also The Murphy Beds.

37. It was reprinted in 1849 in Gazette of the Union, Golden Rule and Odd-fellows' Family Companion, Volumes 10-11; 1849 Published: New York, N.Y.: J. Winchester. The Indiana Quilting Party (with Silver Dagger text) was published first in Spirit of the Times: A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature and the Stage --a weekly newspaper published in New York City, 1849. The last record I have is in the Burlington Weekly Free Press of Burlington, Vermont dated Friday, January 18, 1850 on Page 2.

38. Ballads and Songs, 1940, edited by Belden.

39. Ballads and Rhymes from Kentucky by G. L. Kittredge; The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 20, No. 79 (Oct. - Dec., 1907), pp. 251-277.

40. Ballads and Songs by G. L. Kittredge; The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 30, No. 117 (Jul. - Sep., 1917), pp. 283-369.

41. The only instance I've found where there's a mixture is recent (Max Hunter Collection).

42. Recent versions of the traditional ballad by Joan Baez and years later Dolly Parton were both titled "Silver Dagger."

43. In general both texts are mixed together in references, see for example: Musick- Larkin version. The Traditional Ballad index list recordings of Katie Dear under "Sliver Dagger." The Brown Collection editor says, "Here the story is definitely combined with that of 'The Silver Dagger.' " when the ballad (Brown B) is a traditional version that mentions "silver dagger" and is not part of the composed" ballad.

44. The separation of the two ballads continued with Eddy, Brewster, Randolph, and the Brown Collection.

45. Traditional Ballad Airs, Volume 1, p. 225 by William Christie.

46. John Ord's "Bothy Songs and Ballads," 1930."

47. Two stanzas from Traditional Ballad Airs, Volume 1, p. 225 by William Christie

48. Sung by Mrs. Watt of Whinhill, New Deer, collected by Gavin Greig, c. 1910.

49. The broadside is dated 1690 and is one source for the "True Lover's Farewell" Songs which include "Blackest Crow," "Dearest Dear," and "Ten Thousand Miles." This specific stanza is similarly found in broadside The Sailor's Departure from His Dearest Love:

The fish shall seem to fly,

The birds to fishes turn,

The sea be ever dry

And fire surcease to burn.

50. Gardham's stanza 16 of his composite taken from Greig-Duncan V.

51. The traditional ballad index titles this, "Rise Up Quickly and Let Me In (The Ghostly Lover)."

52. The Len Graham/Joe Holmes stanza found in US (mainly Southwest) versions is:

For I can climb the high, high tree,

And I can rob the wild bird's nest;

And I can pluck the sweetest flower,

But not the flower that I love best.

53. From Sharp and Campbell's English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians I, 1917 and 1932

54. Ibid.

55. B. F. Shelton's 'Oh Molly Dear' recorded on 29 July 1927 in Bristol, Tennessee. Issued as Victor 4017.

56. Guthrie Meade's "Country Music Sources," 2002.

57. It's important to note that all of Flanders versions and all but one of Creighton's versions have not been published but remain in collections.

58. From: "The Drowsy Sleeper" as published by J. Crome of Sheffield; c. 1817; Harding B 28(233).

59. "I Will Set My Ship In Order" as sung by Mrs. Margaret Gillespie of Glasgow, Scotland, c. 1909. Grieg-Duncan C

60. For details of the two ballad types see my article "Supplemental Study: A Comparison of Traditional Texts of The Drowsy Sleeper in North America," following the US/Canada Headnotes.

_____________________________

Ballad Texts:

A. Song XCVII, "Awake, thou fairest thing in nature" from Allan Ramsay's Tea-table Miscellany: A Collection of Choice Songs, Scots & English; Volume 2, dated 1725.

Song XCVII.

He

Awake, thou fairest thing in nature

How can you sleep when day does break?

How can you sleep, my charming creature,

When half a world for you are awake.

She

What swain is this that sings so early,

Under my window by the dawn?

He

'Tis one, dear nymph, that loves you dearly,

Therefore in pity ease my pain.

She.

Softly, else you'll 'wake my mother,

No tales of love she lets me hear;

Go tell your passion to some other,

Or whisper softly in my ear.

He.

How can you bid me love another,

Or rob me of your beauteous charms?

'Tis time you were wean'd from your mother,

You're fitter for a lover's arms.

----------------------

Ba. "O, Who Is This Under my Bedroom Window." From "Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song" by Robert Hartley Cromek, Allan Cunningham, William Gillespie, 1810, reprinted 1880:

This old song is taken down from the singing of Martha Crosbie, from whose recitation Burns wrote down the song of "The Waukrife Minnie." It has a fine affecting tune, and is much sung by the young girls of Nithsdale. Burns has certainly imitated the last verse of it in his "Red, red Rose."

O Who is this under my window?

O who is this that troubles me?"

"O it is ane wha is broken-hearted,

Complaining to his God o' thee."

"O ask your heart, my bonnie Mary,

O ask your heart gif it minds o' me!"

"Ye were a drap o' the dearest bluid in't,

Sae lang as ye were true to me."

"If e'er the moon saw ye in my arms, love,

If e'er the light dawned in my ee,

I hae been doubly fause to heaven,

But ne'er ae moment fause to thee.

"My father ca'd me to his chamber,

Wi' lowin' anger in his ee;

Gae put that traitor frae thy bosom,

Or never mair set thy ee on me.

"I hae wooed lang love—I hae loved kin' love,

An' monie a peril I've braved for thee;

I've traitor been to monie a ane love,

But ne'er a traitor nor fause to thee.

"My mither sits hie in her chamber,

Wi' saute tears happin' frae her ee;

O he wha turns his back on heaven,

O he maun ay be fause to thee!"

"Gang up, sweet May, to thy ladie mother,

An' dight the saute tears frae her ee;

Tell her I've turned my face to heaven,

Ye hae been heaven owre lang to me!"

O up she rose, and away she goes,

Into her true love's arms to fa';

But ere the bolts and the bars she loosed,

Her true love was fled awa.

"O whare's he gane whom I lo'e best,

And has left me here for to sigh an' mane;

O I will search the hale world over,

'Till my true love I find again.

"The seas shall grow wi' harvests yellow,

The mountains melt down wi' the sun;

The labouring man shall forget his labour,

The blackbird shall not sing but mourn,

If ever I prove fause to my love,

Till once I see if he return."

---------------------

Bb. "Who is this under my window?" From Alan Cunningham's Works of Robert Burns: With His Life, Volume 4 (1834).

'An old Nithsdale song seems to have been in the Poet's thoughts when he wrote this exquisite lyric. Martha Crosbie, a carder and spinner of wool, sometimes desiring to be more than commonly acceptable to the children of my father's house, made her way to their hearts by singing the following ancient strain:-

"Who is this under my window?

Who is this that troubles me?"

"O, it is I, love, and none but I, love,

I wish to speak one word with thee.

Go to your mother, and ask her, jewel,

If she'll consent you my bride to be;

And, if she does na, come back and tell me,

This is the last time I'll visit thee."

"My mother's in her chamber, jewel,

And of lover's talking will not hear;

Therefore you may go and court another,

And whisper softly in her ear."

The song proceeds to relate how mother and father were averse to the lover's suit, and that, exasperated by their scorn, and the coldness of the maiden, he ran off in despair: on relenting, she finds he is gone, and breaks out in these fine lines:-

"O, where's he gone that I love best,

And has left me here to sigh and moan?

O I will search the wide world over,

Till my true love I find again.

The seas shall dry, and the fishes fly,

And the rocks shall melt down wi' the sun;

The labouring man shall forget his labour,

The blackbird shall not sing, but mourn,

If ever I prove false to my love,

Till once I see if he return." '

-----------------------------

Ca. THE DROWSY SLEEPER." From Harding B 28(233) printed by J. Crome; Sheffield c. 1817

"Awake, awake, ye drowsy sleeper.

Awake, awake! 'Tis almost day.

How can you sleep, my charming creature,

Since you have stole my heart away?"

"Begone, begone! You will awake my mother.

My father he will quickly hear.

Begone, begone, and court some other,

But whisper softly in my ear."

Her father hearing the lovers talking,

Nimbly jumped out of bed.

He put his head out of the window,

But this young man quickly fled.

"Turn back, turn back! Don't be called a rover.

Jemmy, turn back, and sit you by my side.

You may stay while his passion's over.

Jemmy, I will be your lovely bride."

"O daughter, daughter, I will confine you.

Jemmy he shall go to sea,

And you may write your truelove a letter,

As he may read it when far away."

"O father, pay me down my portion,

Which is five thousand pounds, you know,

And I'll cross the wide watery ocean,

Where all the hills are covered with snow."

"No, I will not pay down your portion,

Which is five thousand pounds, I know;

Nor you shan't cross the wide watery ocean,

Where the hills are covered with snow.

"O daughter, daughter, I will confine you,

And all within your private room;

And you shall live upon bread and water

Once a day, and that at noon."

"No, I will have none of your bread and water,

Nor nothing else that you have.

If I can't have my heart's desire,

Single I will go to my grave."

-----------

Cc. "THE MAIDEN'S COMPLAINT." Harding B 17 (183a). Printer, T. Birt, 10, Great St. Andrew Street, wholesale and retail, Seven Dials, London, Country Orders punctually attended to, Every description of Printing on reasonable terms. Between 1828 and 1829.

Awake, awake, you drowsy sleeper,

Awake, awake, 'tis break of day,

Can you sleep my love any longer,

Since my poor heart you've stole away.

Ah! who is that under my window,

Ah! who comes there to disturb my rest?

'Tis thy lover, the young man did answer

Long thus I have waited for your sake.

Jemmy, says she, should my father hear you,

We shall be ruined I fear;

He will send a cruel press gang for you,

And separate you and me, my dear.

Her father chanc'd to overhear them,

And for a press gang sent straight-way;

Against this young man gave information,

And sent him sailing on the sea.

So now my dear daughter I have deprived you

Of your love whom I have sent to see; (sic)

And now you may send him a letter,

With your misfortunes acquainted to be.

Oh cruel father pay down my fortune

Five hundred pounds is due you know;

And I will cross the briny ocean,

To find my true love I will go.

Jemmy is the man that I do admire,

He is the man that I do adore;,

And if I can't have my heart's desire

Single I will go for evermore.

----------------------

Cd. "AWAKE, DROWSY SLEEPER." from Bodleian Broadside; Firth C17 (25).

Awake, awake, you drowsy sleeper

Awake, awake, it is almost day,

How can you be there and sleep so easy

Since my poor heart you have stole away.

Oh, who is that underneath my window?

Oh who is that that sings so sweet?

It's me, my dear, the young man made answer,

Long time been waiting for your sweet sake.

My mother lies in the next chamber,

My father he will quickly hear

So I'd have you go, love, and court some other,

Or whisper softly in my ear.

Oh no I won't go and court no other,

Since I have rifled your sweet charms

You are fit, love, for to leave your mother,

You're fitter to sleep in your true love's arms.

The old man heard in their conclusion

He gently stept out of the bed,

He popped his old head out of the window

But Jane's true love was gone and fled.

Daughter, daughter, I will close confine you,

Your brisk young lad I will send to sea

Then you may write to him a letter,

And he may read it in Botany Bay.

Jim is the lad that I do admire

Jim is the lad I mean to wed

And if I can't have my own desire

A maid I will go to my silent grave.

Father, father, pay down my portion,

Which is five hundred pounds you know,

That I may cross the briny ocean,

If Botany Bay is covered with snow.

Oh no I won't pay your portion

And you shan't cross the raging main,

For you and your love shall be married,

And that will ease you all of your pain.

----------

Ea. "I Will Put my Ship in Order," from Traditional Ballad Airs, Volume 1, p. 225 by William Christie; 1876.

This Air, unique in its tonality, ending as it does on the note below the minor key-note, was arranged from the way iv was sung by the Editor's maternal grandfather, and from another set sung by a native of Buchan. The Ballad is given as sung by the Editor's grandfather to the air.

I will put my Ship in order.

"Oh, I will put my ship in order,

And I will set her to the sea;

And I will sail to yonder harbour,

To see if my love will marry me."

He sailed eastward, he sailed westward,

He sailed far, far by sea and land;

By France and Flanders, Spain and Dover,

He sail'd the world all round and round;

Till he came to his love's sweet bower,

It was to hear what she would say,—

"Awake, awake, ye lovely sleeper,

The sun is spreading the break of day."

"Oh, who is this at my bower window,

That speaks so lovingly to me?"

"It is your own true constant lover,

That would now have some words with thee.

"Oh, ye will now go to your father,

And see if he'll let you my bride be;

If he denies you come and tell me,—

'Twill be the last time I'll visit thee."

"My father is in his chamber sleeping,

Now taking to him his natural rest,

And at his hand there lies a letter,

That speaketh much to thy dispraise."

"To my dispraise,love!" "To thy dispraise,love!"

"To my dispraise! how can that be?

I never griev'd you, nor once deceived you,

I fear, my love, you're forsaking me.

But you will now go to your stepmother,

And see if she'll let you my bride be;

If she denies you come and tell me,—

'Twill be the last time I'll visit thee."

"My mother is in her bower dressing,

And combing down her yellow hair;

Begone, young man, you may court another,

And whisper softly in her ear."

Then hooly, hooly, raise up his lover,

And quickly put her clothing on;

But ere she got the door unlocked,

Her true lover now was gone.

"Oh, are ye gone, love? are ye gone, love?

Oh, are ye gone, and now left me?

I never griev'd you, nor yet deceiv'd you,

But now, I fear, you are slighting me."

"The fish shall fly, love, the sea shall dry, love,

The rocks shall all melt wi' the sun;

The blackbird shall give over singing,

Before that I return again."

"Oh, are you gone, love? are you gone, love?

Oh, are you gone, and left me now?

It was not me, it was my stepmother,

That spoke to you from her bower window."

He turned him right and round so quickly,

Says, " Come with me, my lovely one,

And we'll be wed, my own sweet lover,

And let them talk when we are gone."

-------------------

______________________

Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Volume 2, Issues 6-9

By Folk-Song Society (Great Britain)

Compare this song with "O, who is that that raps at my window?" (Folk-Song Journal, vol. i, No. 5), and "Go from my window, love, go" (Johnson's Museum), also with the following tunes and words from Christie's Traditional Ballad Airs of Scotland. Christie's second air was noted from a native of Buchan. The first air and the words are as sung by his grandfather. I have met with several ballads sung by illiterate persons in the South of England, which contain the greater and most characteristic part of Burns's lyric, with, moreover, additional stanzas of quaint beauty and imagery which, together with their general type, convince me that Burns borrowed his most ardent lines from an old country song, when writing " O my luve's like a red, red rose."

______________________

And now he is standing on the other side of this very wall; now he is looking through each window in turn, peering through every chink. I can hear my true love calling to me, Rise up, rise up quickly, dear heart, so gentle, so beautiful, rise up and come with me. (Sg. 2:9-10; Knox Translation)

"Rise Up Quickly and Let Me In"

Northumbrian Minstrelsy (1882). It's the major-key tune and includes the "ripest apples" verse. The last line of that verse is "True love is timid, so be not bold",

"I Am a Bold Defender," tune in The Fiddler's Companion:

The original as I have it, from Bruce & Stokoe, has the last verse:

He's brisk and braw, lads, he's far awa' lads,

He's far beyond yon raging main,

Where fishers dancing, and dark eyes glancing,

Have made him quite forget his ain.

"Oxford City".

"I Drew My Ship"

--------------------

There is also an English folk song (Roud 1362) of which oral versions have the title 'Over the hills and the mountains/Over hills and high mountains'. It can be traced back to 17thc broadsides. There's a more recent broadside at the Bodl. Harding B22 (381). It also features as 'Over Hills and High Mountains' in Chappell. The 17thc version is called 'The Wandering Maiden'.

I have not found any song or ballad commencing " On yonder high mountains," but " Over hills and high mountains" was a very popular ballad in the latter part of the preceding century, and the tune was often referred to.

This is evidently a ballad tune, and as the metre of ' Over hills and high mountains "exactly suits it, as well as the character of the words, it is probably the right air.

Copies of "Over hills and high mountains" are in the Bagford Collection, 643, m. 10, p. 165, and in the Pepys Collection, iii. 165. The ballad is entitled "The Wandering Maiden; or, True Love at length united," &c.: "to an excellent new tune." "Printed by J. Deacon, at the Angel in Guiltspur Street, without Newgate." It commences thus :—

"Over hills and high mountains long time have I gone;

Ah ! and down by the fountains, by myself all alone;

Through bushes and briars, being void of all care,

Through perils and dangers for the loss of my dear."

In the Roxburghe Collection, ii. 470, is "True love without deceit," &c.: "to the tune of Over hills and high mountains "; commencing : —

"Unfortunate Strephon! well may'st thou complain,

Since thy cruel Phillis thy love doth disdain."

------------------

1-14

The Grey Cock

(Roud 179, Child 248)

Recorded by Marie Slocombe and Patrick Shuldham-Shaw, 30.11.51

I must be going, no longer staying

The burning Thames I have to cross

Oh I must be guided without a stumble

Into the arms of my dear lass.

When he came to his true love's window

He knelt down gently on a stone

And it's through a pane he whispered slowly

“My dear girl, are you alone?”

She rose her head from her down-soft pillow

And snowy were her milk-white breast. Saying,

“Who's there, who's there at my bedroom window

Disturbing me from my long night's rest?”

“Oh I'm your lover, don't discover

I pray you rise, love, and let me in

For I am fatigued out of my long night's journey

Besides I am wet into the skin.”

Now this young girl rose and put on her clothing

‘Til she quickly let her own true love in.

Oh they kissed, shook hands

and embraced each other

‘Til that long night was near at an end.

“Willie dear, O dearest Willie

Where is that colour you'd some time ago?”

“O Mary dear, the clay has changed me

I am but the ghost of your Willie O.”

“Then O cock, O cock, O handsome cockerel

I pray you not crow until it is day

For your wings I'll make

of the very first beaten gold

And your comb I will make of the silver ray.”

But the cock it crew and it crew so fully

It crew three hours before it was day

And before it was day my love had to go away

Not by the light of the moon

nor the light of day.

When she saw her love disappearing

The tears down her pale cheeks

in streams did flow

He said, “Weep no more for me, dear Mary

I am no more your Willie O.”

“Then it's Willie dear, O dearest Willie

Whenever shall I see you again?”

“When the fish they fly, love,

and the sea runs dry, love

And the rocks they melt by the heat of the sun.”

This ballad is variously called

The Lover's Ghost, Willie's Ghost

and

The Grey Cock

.

Mrs Costello seemed to prefer the last, which she sometimes abbreviated to The Cock. It is perhaps the classic ‘revenant ballad’, having almost all the motifs usually found in such songs. As most of today’s TV viewers will know, ‘Les Revenants’ are ‘The Returned’, so ‘revenant ballads’ deal with ghostly visitations from dead lovers. They can be quite difficult to separate from ‘night visiting songs’, which usually have a very similar plot, except for the “I am but the ghost of your Willie-O” line; after which Willie and Mary consummate their present love - rather than talk of their past one -and part when the cock crows. The ballad was circulating in England as early as the seventeenth century, but no version finer than Mrs Costello's has been collected. She believed that the ghostly lover was a soldier, and that the visit to his lover took place while his body lay mortally wounded on the battlefield. The cock's summons to the ghost to return indicated that the death of the soldier was about to take place.

Since revenant ballads’ are fairly common, it’s quite a surprise to find that this one has only 74 Roud entries, although it has been heard all over these islands and North America. There have been 25 sound recordings, about half of which have been published at some time. Sadly, only those by: Maggie Murphy (MTCD329-0); Vergie Wallin (MTCD503-4); Bill Cassidy (MTCD325-6); Ellen Mitchell (MTCD315-6); Roisin White (VT126CD); and Duncan Williamson, on the CD accompanying the book Traveller’s Joy (EFDSS, 2006) have made the transition to the CD medium.

-----------

Reliques of Robert Burns, consisting chiefly of original Letters, Poems, and Critical Observations on Scottish Songs. Collected and published by R. H. Cromek. 8vo. pp. 453. London, Cadell and Davies, 1808.

---------------

"The Unkind Parents, or, The Languishing Lamentation of two Loyal Lovers" 1690

The Unkind Parents:

OR,

The Languishing Lamentation of two Loyal Lovers.

To an Excellent New Tune.

Licensed according to Order.

(1.) Now fare thou well my Dearest Dear, and fare thou well a while,

Altho' I go, I'll come again; if I go ten thousand mile, Dear Love,

if I go ten thousand mile.

(2.) Ten thousand miles is far, dear Love, for you to come to me,

Yet I could go full ten times more, to have thy company, dear Love,

to have thy, etc.

(3.) Thou art my Joy and chief delight, Love, leave me not behind,

If from my presence you take flight, then are you most unkind, dear Love,

then are, etc.

(4.)