Broadside Illustration by J. Harkness, circa 1850 Preston

Narrative: 5. A-Growing (The Trees They Do Grow High)

A. "My Love is Long A-Growing," two stanzas from David Herd (1732–1810) of Edinburgh dated 1776 or later, from "Songs from David Herd’s Manuscripts. Edited with Introduction and Notes by Hans Hecht, Dr.: Phil (Edinburgh: William J. Hay), 1904.

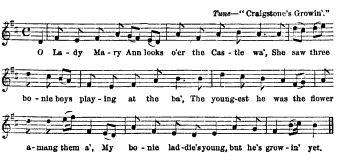

B. "Lady Mary Ann," five stanzas from Robert Burns, 1787, dated 1792 in James Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum, the original first stanza from his MS (see below) was never published. Burn's first two published stanzas are similarly found in A.

C. "Craigston's Growing," dated pre-1818, from Rev Robert Scott, b. 1778, who was minister at Glenbucket from 1808 until his death in 1855. From: The Glenbuchat Ballads; edited by David Buchan, James Moreira, 2007.

D. "My Bonnie Laddie's Lang o' Growing," from Motherwell, c. 1819, Paisley. Motherwell contributed the first stanza (no date given) which was published in the notes to "Lady Mary Ann." The full ballad was published as a footnote in The Works of Robert Burns, IV, 1845.

E. "The Young Laird of Craigstoun," from A North Countrie Garland, 1824, edited by James Maidment who received the ballad Nov. 9, 1822 from David Webster-- text from James Nicol of Strichen.

F. "The Lament of a Young Damsel for her Marriage to a Young Boy," dated c. 1825 from Emily Lyle's "Andrew Crawfurd's Collection of Ballads and Songs," II, #122, 1996, from Elizabeth "Bethia" Macqueen, Aberdeenshire.

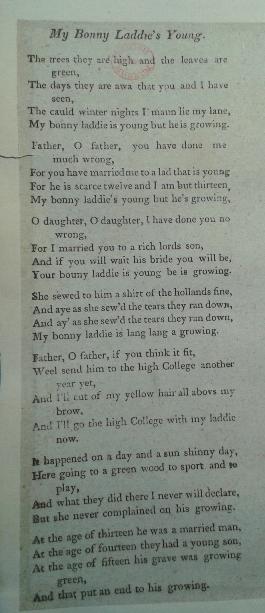

G. "My Bonny Laddie's Young," Scottish broadside at the British Library (ref. 1871 f 13 item 60a) dated c. 1825 (1820s-1830s by Steve Roud). The broadside was transcribed twice in Sabine Baring-Gould's notebooks, with only one (incorrect) line for first stanza. The first stanza was written down from the broadside by Steve Gardham in 2011. In Sept., 2016 a copy was obtained from Steve Roud via Steve Gardham and given to me.

H. "My Love A-Growing," dated c.1856, recited by Bell Robertson to Gavin Grieg about 1907 in New Pitsligo, Scotland. From: The Greig-Duncan Folk Song Collection, Volume 6 by Patrick N. Shuldham-Shaw, Emily B. Lyle; Aberdeen University Press, 1995.

I. "My bonny lad is young, but he's growing," a Such broadside, dated c. 1863, London: H. Such, Machine Printer & Publisher, 177, Union Street, Borough, S.E. This is a 2nd printing, the first is dated c. 1850.

J. "My Bonny Boy is Young but he's Growing," dated about 1880, is broadside No. 756 by H. J. Wehman of 50 Chatham St., New York, which was the first version published in the US. The text was reprinted in Good Old-time Songs, Issue 3 by Wehman bros., publishers: 1914.

K. "Young Craigston," from Traditional Ballad Airs (Vol. 2), Christie, 1881-- no informant named. It was taken down by Christie from a resident of Buchan.

L. "The Trees They Are So High," sung by James Parsons of Lew Down. Collected in 1888 by Baring-Gould.

M. "My Bonny Boy," Irish version sung by Mary O'Bryan of Abbey View, Cahir, Tipperary, learned from an old lady in West Clare in August, 1890; from Sabine Baring-Gould's Manuscript Collection online.

N. "All the Trees They are so High," attributed to Mrs. Mason in the program "Words of Songs" sung at Baring-Gould's first lecture, "Ballad Music of the West of England" on 31 May, 1890 at the "Royal Institiution" on Albermarle St. See: Sabine Baring-Gould Manuscript Collection (SBG/2/2/290).

O. "Growing," sung by William Aggett, aged 70, crippled and infirm, of Chagford as collected by Sabine Baring Gould on Sept. 30, 1890.

P. "Oh, The Trees are Getting High" sung George Ede of Dunsfold, Surrey, in 1896; collected by Lucy Broadwood. From English Traditional Songs and Carols edited by Lucy Broadwood, 1908; also Journal of the Folk-Song Society, I (4) 1904, 214-5.

Q. "The Trees They Do Grow High," sung by Mr. Harry Richards, at Curry Rivell, July 28th, 1904. Collected by Cecil Sharp. Published in Folk songs from Somerset by Sharp, Marson- 1904; also Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Volume 2 by Folk-Song Society (Great Britain)- 1905.

R. "The Trees They Do Grow High," sung by David Penfold, Landlord of the Plough Inn at Rusper, Kingsfold, Sussex on May 3, 1907; collected by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

S. "The Trees They Do Grow High," sung by William Smith, Stoke Lacy, Herefordshire in Sept., 1907. Collected by George Butterworth,

T. "Young But Growin" sung by James Cheyne, (of Aberdeen?) collected by Gavin Greig, c. 1908. From: The Greig-Duncan Folk Song Collection, Volume 6 by Patrick N. Shuldham-Shaw, Emily B. Lyle; Aberdeen University Press, 1995.

U. "The Trees They Do Grow High" from Stephen Spooner, of Midhurst Union, Sussex on Oct. 18, 1911; collected by Clive Carey as taken from the Clive Carey Manuscript Collection (CC/1/128).

V. "My Bonny Lad Is Young," sung by Mrs. Joiner of Chiswell Green, Hertfordshire,, Sept. 7th, 1914. collected by Broadwood From: Songs of Love and Country Life by Lucy E. Broadwood, Cecil J. Sharp, Frank Kidson, Clive Carey and A. G. Gilchrist

Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Vol. 5, No. 19 (Jun., 1915), pp. 174-203.

W. "Daily Growing," sung by James Atwood, a farmer and mason in West Dover, Vermont. Collected and published by Helen Sturgis, 1919, published in her Songs from the Hills of Vermont.

X. "Daily Growing," sung by Bridget Hall, Conception Bay, Newfoundland, October, 18, 1929. Collected by Maud Karpeles.

Y. "Young But A-Daily Growing," sung by Grammy Fish of New Hampshire, probably originating in Vermont, recorded Flanders and Olney on 11-16-1940. Also collected in 1940 by Frank and Ann Warner.

Z. "He's Young but Daily Growing," sung by Mrs Duncan of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia collected by Creighton, before 1950. From: Traditional Songs From Nova Scotia, 1950.

AA. "The Trees They Do Grow High," sung by Bob Copper, Sussex as learned from Seamus Ennis c.1952; From: VT131CD; a Veteran CD: When the May is all in Bloom, 1995.

BB. "The Trees are Growing Tall," sung by Pat Kelly, Newry, Co. Down on 31st July, 1953 as recorded by Peter Kennedy and Sean O'Boyle. From: Some 'English' Ballads and Folk Songs Recorded in Ireland 1952-1954; Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, Vol. 8, No. 1 (1956), pp. 16-28.

CC. "Young but Growing," sung by Margaret McGarvey of Belleck, Co Fermanagh, Aug 11, 1954, recorded by Seamus Ennis. Appears on Good People, Take Warning: Ballads sung by British and Irish traditional singers.

DD. "The College Boy," sung by Lizzie Higgins, first recorded by Sandy Paton, 1958. Subsequent recordings include Princess of the Thistle; 1969 and from Musical Traditions Records' first CD release of 2006: Lizzie Higgins 1929-1993: In Memory of (MTCD337-8).

EE. "My Bonny Boy Is Young," sung by Joe Heaney of Carna, Ireland in 1964. Recorded by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger.

FF. "The Bonny Boy," sung by Fred Jordan, a farm worker from Shropshire, as recorded by Bill Leader and Mike Yates in a private room in The Bay Malton Hotel, Oldfield Brow, Altringham, Cheshire, in 1966.

GG. "Long a-Growing," sung by Mary Ann Haynes, Brighton, 1974, collected by Mike Yates. From Sussex Harvest, a Topic anthology, 1998.

HH. "The Trees They Do Grow High," sung by Walter Pardon of Knapton, Norfolk in 1974, from the recording, Walter Pardon: A World Without Horses TSCD514.

II. "The Trees They Grew High," sung by Pat MacNamara (1895-1977) of Kilshanny, near Ennistymon; recorded in Kilshanny, in August, 1975 from the Carroll/Mackenzie Collection.

__________________________

A, from David Herd's MSS[1] written in his hand about 1776, is a two stanza fragment titled, "My Love is Long A-Growing." Herd's only comment is found in the margin, "A very fine tune not in any collection MSS." Herd's fine tune has not been found. The possibility exists however that Herd gave the tune to Robert Burns or James Johnson. Here are Herd's two stanzas:

She look’d o’er the castle wa’,

She saw three lads play at the ba’,

O, the youngest is the flower of a’,

But my love is lang o’ growing.

‘O father, gin ye think it fit,

We’ll send him to the college yet,

And tye a ribban round his hat,

And, father, I’ll gang wi him!’

From this fragment it's unclear that the ballad is about an arranged marriage of a young girl by her father to a boy who is even younger than she. That this boy, "the flower of all," is going to "college" is another clue about the mystery of this ballad's origin.

Lady Mary Ann- R. Burns, 1787;

B, titled "Lady Mary Ann," (see above) is a five-stanza song from Robert Burns whose MS was entered into Johnson's Musical Museum in 1792. According to Dr. Hans Hecht[2], Burns "used the two verses [from Herd's MS] almost literally in his song Lady Mary Ann." Here are Burns' first two stanzas:

O Lady Mary Ann looks o’er the castle wa’,

She saw three bonnie boys playing at the ha’,

The youngest he was the flower among them a’;

My bonnie laddie’s young, but he’s growin’ yet.

“O father, O father, an' ye think it fit,

We’ll send him a year to the college yet;

We’ll sew a green ribbon round about his hat,

And that will let them ken he’s to marry yet.

Motherwell and Stenhouse have asserted that Burns "noted the song and the air from a lady in 1787, during his tour in the North of Scotland.[3]" Stenhouse explains that "the Burns is modelled on an antique fragment, Craigton's[sic] Growing, in a Ms. collection belonging to Rev. Robert Scott, of Glenbucket[4]," my C.

Since Burns' fifth stanza is also based on tradition, it seems likely that his first two stanzas (similar to Herd's) and his last stanza came from this lady in the Scottish highlands in 1787. The third and fourth stanzas, as well as the title and proper names inserted into the song, have been credited to Burns. James Kinsley in his "Poems and Songs of Robert Burns" (1968) suggests that Burns' three traditional stanzas came from tradition despite the first two being nearly identical to Herd's. I agree with Kinsley that three of Burns' stanzas are probably taken from tradition because of two little details: 1) Burns has "green ribbon" in his second stanza, third line-- and 2) Burns' second stanza, fourth line is quite different than Herd's (see above). The "green ribbon" has been found in other traditional versions including Elizabeth Macqueen's (c. 1825 in Andrew Crawfurd's Collection of Scottish Ballads and Songs). John Finlay in his The Annual Review, and History of Literature (1809) gave the text of "Lady Mary Ann" and reported: "The green ribbon, among lovers, is the symbol of hope." Finlay's symbol has been echoed by other writers. Although the color in some early Scottish versions is green, it's often blue or white and the ribbon is tied around his waist or elsewhere.

Lady Mary Ann was No. 38 of sixty questionable ballads Grundvig sent in a letter to Child about 1870. Grundtvig listed Lady Mary Ann as published by Motherwell and after his listing Grundtvig wrote: (Suspicious). Since Motherwell published Burns' text in his Minstrelsy, it was printed as a broadside and a number of versions have been collected that have entered tradition (for example, two from Greig-Duncan). In 1843 Lady Mary Ann was arranged for the piano by Robert Chambers in his "Twelve Romantic Scottish Ballads: With the Original Airs." A different "original air" than Burns' air of "Craigston's Growing" was wed by Chambers to four stanzas of Robert Burns' standard text. He reports in his notes: "The air [Craigston's Growing] is from the playing of a lady, who learned it about forty years ago [1803] from a nurse-maid at Dundee." However, the original text was wanting.

The approximate age of the "Trees" ballad may be determined in part from a Scottish tune entitled "Long a-Growing" which is in Guthrie's MSS (c. 1675-80) and is over one hundred years older than Burns' and Chambers' tunes. Bruce Olsen reported that the tune is in Italian viola de braccia tablature and suggests it's value is minimal[5]. Still, it suggests that the ballad had circulation at that time (c. 1675) in Scotland.

Rev. Robert Scott (b. 1778), was minister at Glenbucket from 1808 until his death in 1855. His version, "Craigston's Growing" (C) is dated pre-1818 but not before 1808, and appears in "The Glenbuchat Ballads" edited by David Buchan, James Moreira. The 5th stanza of Burns' Lady Mary Ann closely resembles a stanza from Scott's "Craigston's Growing"[6]. Rev. Scott's version or a similar one which Burns heard in 1787 shows the ballad clearly predates the 1818 Glenbuchat date and 1787 Burns' date. Craigston's Growing's importance cannot be underestimated-- it is the first and oldest complete version that tells the old ballad story.

As pointed out previously it is believed that Burns' published 1792 version of the ballad is made up of Herd's two tradition stanzas, a traditional stanza from another source(the last) and recreated 3rd and 4th stanzas. The original first stanza is missing in his published versions. In the annotated version in James Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum, Burns writes, "the starting verse should be restored[7]" and gives this verse:

Lady Mary Ann gaed out o’ her bower,

An’ she found a bonnie rose new i’ the flower;

As she kiss’d its ruddy lips drapping wi’ dew,

Quo’ she, ye’re nae sae sweet as my Charlie’s mou’.”

This missing stanza is also the work of Burns pen although parts of it seem to be from tradition. He probably thought it did not fit the opening and chose not to use it. Later he recanted and recommended that it be restored. Although poetic, it does nothing to add to the song. As with his "Red, Red Rose," Burns' "Lady Mary Ann" is taken mainly from tradition (via a version he heard in the Highlands) and recreated. The addition of the names Lady Mary Ann and Charlie are certainly from Burns' pen and not from tradition. Stanzas 1,2 (A) and 5, (C) of his published version (5 stanzas) are based on tradition whilst 3 and 4 come from Burns' pen. Burns' poetry does not reveal the ballad story and clearly Burns' knew not Craigston's Growing.

D, titled "My Bonnie Laddie's Lang o' Growing," was supplied by Motherwell as "traditionally preserved in the west of Scotland" which I've dated c. 1819 when Motherwell had moved to Paisley. It was published by Ord in Bothy Ballads without attribution and used by MacColl as his opening stanza. It begins:

The trees they are ivied, the leaves they are green,

The days are a' awa that I hae seen;

On the cauld winter nights I ha'e to lie my lane,

For my bonnie laddie's lang o' growing.'

With the publication of E in 1824, "The Young Laird of Craigstoun," came the detailed explanation about the origin of the ballad: that it was based on the Laird of Craigstoun, John Urquhart, who died in 1634. The Craigstoun name, given by James Maidment, was also found in "Craigton's growing" heard by Burns in the Highlands in 1787 which is more commonly spelled, "Craigston's Growing." The historic events and people found in the ballad as reported by Maidment have been generally accepted by researchers and writers until recently[8]. I'm giving E and the notes by James Maidmant in their entirety. The ballad, now attributed to James Nicol[9] of Strichen, is said by one critic to be rubbish[10]. Here's the complete text and notes from A North Countrie Garland, Volume 2; edited by James Maidment, Edmund Goldsmid, 1824:

* * * *

THE YOUNG LAIRD OF CRAIGSTOUN.

The estate of Craigstoun was acquired by John Urquhart, better known by the name of the Tutor of Cromarty. It would appear that the ballad refers to his grandson, who married Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Robert Innes of that ilk, and by her had one son. This John Urquhart died November 30, 1634. Spalding (vol. i. p. 36), after mentioning the great mortality in the Craigstoun family, says: "Thus in three years' space the good-sire, son, and [b]oy died." He adds that "the Laird of Innes (whose sister was married to this Urquhart of Leathers, the father), and not without her consent, as was thought, gets the guiding of this young boy, and without advice of friends, shortly and quietly marries him, upon his own eldest daughter Elizabeth Innes." He mentions that young Craigstoun's death was generally attributed to melancholy, in consequence of Sir Robert Innes refusing to pay old Craigstoun's debts: the creditors bestowing "many maledictions, which touched the young man's conscience, albeit he could not mend it." The father died in December, 1631, and the son in 1634. The marriage consequently must have been of short duration.

"Father," said she, "you have done me wrong,

For ye have married me on a childe young man,

For ye have married me on a childe young man,

And my bonny love is long

A growing, growing, deary,

Growing, growing, said the bonny maid,

How long my bonny love's growing."

"Daughter," said he, "I have done you no wrong,

For I have married you on a heritor of land,

He's likewise possessed of many bills and bonds,

And he'll be daily

Growing, growing, deary," &c.

"Daughter," said he, "if you wish to do well,

Ye will send your husband away to the school,

That he of learning may gather great skill,

And he'll be daily

Growing, growing, deary," &c.

Now young Craigstoun to the college is gone,

And left his lady making great moan,

That she should be forced to lie a-bed alone,

And that he was so long

A-growing, growing, &c.

She's dressed herself in robes of green,

They were right comely to be seen,

She was the picture of Venus' queen,

And she's to the college to see[11]

Him growing, growing, &c.

Then all the Colleginers were playing at the ba',

But the young Craigstoun was the flower of them a';

He said, "Play on, my schoolfellows a',

For I see my sister

Coming, coming," &c.

Now down into the college park

They walked about till it was dark,

Then he lifted up her fine Holland sark,

And she had no reason to complain

Of his growing, growing, &c.

In his twelfth year he was a married man,

In his thirteenth year then he got a son;*

And in his fourteenth year his grave grew green,

And that was the end

Of his growing, growing, &c.

*By the extinction of the elder branch of the family this son succeeded to the estate of Cromarty.

* * * *

The information on which Maidment based his conclusion of the origin was from Spalding in 1792 who unfortunately got some of the facts confused perhaps because it was more that 150 years after the incident. The most obvious error was his failure to identify "that the young boy" was Alexander Brodie, implying instead that it was John Urquhart, who was briefly the Laird of Craigston[12]. Here is Spalding's paragraph from The history of the troubles and memorable transactions in Scotland, 1792:

Ye heard before of the death of John Urquhart of Craigstoun, and how his eldest son John Urquhart of Leathers shortly followed; his son again departs this life upon the last of November instant. Thus in three years space the goodsire, son, and [b]oy, died. It is said this young man's father willed him to be good to Mary Innes his spouse, and to pay all his debts, because he was young and had a good estate, whereunto his goodsire had provided him; the young boy mourning past his promise so to do, then he desires the laird of Cromartie being present to be no worse tutor to his son than his father had been to him, and to help to fee his debts paid, being then above 40,000 pounds, for the whilk several gentlemen in the country were heavily engaged as cautioners. The laird of Innes (whose sister was married to this John Urquhart of Leathers) and not without her consent, as was thought, gets the guiding of this young boy, and without advice of friends, shortly and quietly married him upon her own eldest daughter Elizabeth Innes. Now Leathers' creditors cry out for payment against the cautioners; the cautioners crave Craigstoun, and the laird of Innes his father in law (who had also the government of his estate) for their relief. The young man was well pleased to pay his father's debt, according to his promise, albeit he was neither heir nor executor to him. Yet his goodfather, seeing he could not be compelled by law to pay his father's debt, would in noways consent thereto; there followed great outcrying against him; friends met and trysted; at last it resolved in this, the creditors compelled the cautioners to pay them completely to the hazard of the sum of their estates, and they got some relies, others little or none, which made the distressed gentlemen to pray many maledictions, which touched the young man's conscience, albeit he could not mend it. And so through melancholy, as was thought, he contracts a consuming sickness, whereof he died, leaving a son behind him called John, in the keeping of his mother, and left the laird of Innes and her to be his tutors, without advice of his own kindred, which is remarkable, considering the great care and worldly conquest of his goodsire to make up an estate to fall in the government of strangers. This youth deceased in the place of Innes, and was buried beside his father in his goodsire's isle in Kinedwart.

The underage boy was guided by Sir Robert Innes who was crowned Baronet of Nova Scotia in 1625 and was appointed a Privy Councillor to represent Moray by Charles I-- Innes was a powerful man of high social standing. Sir Robert "without advice of friends, shortly and quietly married him upon her[his] own eldest daughter Elizabeth Innes[13]." This boy was not John Urquhart, who had just died and he obviously wasn't his one year old son, also John Urquhart[14], but he was rather-- 17 year old Alexander Brodie, who had just returned from King's College and was heir to his recently deceased father's estate when Alexander came of age.

In the ballad, a father arranges his daughter's marriage to a young boy. In Ian Pittaway's recent article[15] he pointed out that the John Urquhart of Cragiston was older than his wife, Elizabeth Innes and could not reasonably be the young boy in the ballad. The only juvenile husband associated to that clan in Aberdeenshire at that time was Alexander Brodie, Elizabeth's second husband, who was reported to be seventeen at the time of marriage in 1635.

Elizabeth Innes was the eldest daughter of the Dec. 18, 1611 marriage of Sir Robert Innes and Grizel Stewart, who was the daughter of The Bonny Earl of Murray (Moray). Not only does Grizel have a ballad about her daughter but she has another ballad is about her father's murder! I have a date of c. 1613 for Elizabeth's birth-- there is also a date given online of 1621 which makes no sense. The most telling reason that the 1621 birth date is incorrect: it was 10 years after the Innes/Stewart marriage and Elizabeth was the eldest of their five daughters. It should be noted Robert and Grizel also had three sons-- they would not have waited 10 years to start their family!

Regardless of the accuracy of the following corresponding genealogical dates[16], this is what I think happened:

1) In 1631 John Urquhart inherited the Estate of Craigston (also Craigton or Craigstoun) in Aberdeenshire from his grandfather, John Urquhart-- the Tutor of Cromarty. The Estate would normally go to his son, John Urquhart of Laithers, but he was a poor manager and was not in line to inherit. John Urquhart-- the Tutor of Cromarty-- died in 1631 and his son died a month later so his grandson became the Lord of Craigston. Along with the title, Urquhart inherited a large debt with the Estate.

2) John Urquhart of Cragiston (b. 1611) married Elizabeth Innes (b. 1613) in 1632.

3) They had issue in 1633 one child, Sir John Urquhart who became the heir of Craigston. He died in 1678 but had a son who continued the line.

4) On Nov. 30, 1634 Elizabeth's husband John Urquhart died of a "consuming seikness" leaving a son[17], also John Urquhart who is mentioned above in 2).

5) In 1632 fourteen-year old Alexander Brodie returned from King's College[18] in Aberdeen because of the death of his father. Alexander was to become heir to The House of Brodie, one of the established clans of Morayshire, when he became of age. After the funeral he returned to King's College where he matriculated during the years 1632, 1633 and possibly 1634. I assume he came home when classes were not in session, and during this time or shortly after the death of John Urquhart, he met Elizabeth Innes. The meeting was likely through an introduction from her father, Sir Robert Innes (as reported by Spalding), her mother Grizel Stewart, the daughter of the Bonny Earl of Murray(Moray) or as reported in Scottish Notes and Queries (1931, p. 40): "Her aunt, 'Dame Marie,' is said to have arranged her marriage." At the request from her father but not without her permission, Elizabeth Innes married Alexander when he was underage--a boy, the age of 17. It's possible, as in the ballad, that she may have gone to his college to see him. The ballad is clearly about a college boy-- one of the most compelling reasons to conclude that the ballad is about the Alexander Brodie/Elizabeth Innes relationship.

6) Whatever the reasons, one being his young age, Brodie (not Urquhart),was "shortly and quietly" married to Robert Innes' "own eldest daughter Elizabeth Innes" [see Spalding] in 1635 less than year after John Urquhart's death. Elizabeth was about 4 years older than Alexander. Her age is determined by the following facts in evidence:

Sir Robert was married to Grizel Stewart in 1611.

They had eight children--Elizabeth was the eldest of five daughters and married first.

Elizabeth was born about 1613 and Brodie's birth date is known--he was born in 1617. Because Elizabeth married less than a year after her husband died, it brings into question the actual length and circumstances of the relationship with Alexander Brodie. The nature of John Urquhart's "consuming seikness" which ultimately led to his death in 1634, indicate that Urquhart's condition, rumored to be brought about by his burden of debt, was an ongoing one-- and perhaps the marriage was doomed from the start.

7) John Urquhart of Craigston died of a "consuming seikness" at the House of Innes on November 30, 1634. After his death it was possible and even likely that her father, Sir Robert Innes, obliged his daughter Elizabeth to marry young Alexander, although Spalding says it was "not without her consent, as was thought[19]." There were several advantages of this marriage. First, it would free her from the burden of debt that became John Urquhart's in 1931. Despite the cautioner's demand for payment of the Urquhart debt and the young Brodie's willingness to repay it, Sir Robert Innes knew that Brodie was not legally obligated to repay the debt (and his position prevailed). And second, it would place his widowed daughter who had a one-year-old son, in a new marriage with young Brodie who, although underage, was soon to be heir to the House of Brodie (his father died in 1632), one of the original clans of Morayshire. Brodie's life was one of power and privilege. In 1649, just nine years after Elizabeth's death he was appointed a lord of session as Lord Brodie. He was also one of the Commissioners from Scotland sent to Holland by Charles II in 1949 and 1650.

8) Another reason for Urquhart's death, besides the burden of debt associated with the estate he inherited from his grandfather in 1631[20], was a pledge he made to his father to care for his mother (Mary nee Innes- Robert's sister)-- a pledge that added more pressure upon him and was a pledge that Urquhart could not keep.

The balladeer could have easily assumed these facts: Young Craigston (a name and title erroneously given to the young Alexander Brodie) was a young handsome boy who went off to college (King's College). A young woman's father (Sir Robert Innes) had arranged for his daughter (Elizabeth Innes) to marry this college boy who she subsequently visited and watched playing ball at school.

Even though it was John Urquhart who died, leaving her a widow with a one year old son-- the balladeer could easily have assigned those facts to Alexander -- her husband less that a year later. For one year after his son was born, Urquhart was under the sod in his grave. Elizabeth was left to raise her baby after her husband was gone:

7. In's fourteenth year he was a married man

In's fifteenth year he had a young son.

In's sixteenth year his grave grew green

Alas! for Craigston's growing[21].

This version of the ballad is only a few years off the actual marriage age-- Brodie was a married man in his seventeenth year. Other versions, like the one Cecil Sharp collected in Appalachia, have "At the age of sixteen he was a married man." In some versions he's twelve years old or seventeen or eighteen and in one-- he's seven years old, which exaggerates the point-- he's young but he's daily growing. In real life Alexander and Elizabeth had two children, a son and a daughter, shortly after they married. I believe that she was the love of his life- for after she died when he was only 23 (in 1640)-- he never remarried.

In The Diary of Alexander Brodie of Brodie, by Alexander Brodie [edited by David Laing in 1863 which may be read online at Google books] we find this brief biographical information about his early life:

Alexander Brodie Of Brodie, the Author of this Diary, was born the 25th of July, 1617. "1 was sent," he says, "into England, in Anno 1628, being little more than ten years old, and returned in Anno 1632, in which my Father of precious memory deceased." Of his early history we have no other particulars, excepting that in the years 1632 and 1633, he was enrolled as a Student in King's College, Aberdeen, but did not take his degree of Master of Arts. On being of age, he was served heir of his father, 19th May, 1636, by dispensation of the Lords of Council; but on the 28th of October, the previous year, he had formed a matrimonial alliance with the relic of John Urquhart of Craigston, tutor of Cromarty, who died 30th March, 1634. This lady to whom he was most devotedly attached, was Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Robert Innes of Innes, Bart., by Lady Grizzel Stewart [Stuart], daughter of James, second Earl of Murray. The young Laird of Brodie, when twenty-three years of age, had to bewail the loss of his wife, who died 12th of August, 1640, leaving one son and one daughter.

The same version of E was published by Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe with mostly minor changes in 1839. Sharpe's version came from an MS in his transcript (a small octavo of 22 pages) at Broughton House which was received probably from ballad hawker David Webster who made handwritten copies of the ballad which he recovered from James Nicol of Strichen (d.1840)-- a copper and bookseller in Aberdeenshire[22]. The famous line, "Then he lifted up her fine Holland sark," in the penultimate stanza was edited out of C.K. Sharpe's published text. Also this ballad was found in the Sir Walter Scott transcript, North Country Ballads. The ballad is attributed by David Buchan to James Nicol of Strichen, who was an informant for Peter Buchan. Many of Nicol's ballads were published by Child.

F, titled "The Lament of a Young Damsel for her Marriage to a Young Boy," is dated c. 1825 and appears in Emily Lyle's "Andrew Crawfurd's Collection of Ballads and Songs," II, #122, 1996, six stanzas. The informant was Elizabeth "Bethia" Macqueen (also McQueen), born in County Down, who married Robert Orr in Ayrshire in 1828. She was the sister of poet Thomas MacQueen who was paid by Crawfurd to collect ballads[23].

G, "My Bonnie Laddie's Young," is a Scottish broadside that was transcribed circa 1890 by Sabine Baring-Gould from the British Museum library. He did not write the first stanza down accurately and abbreviated it in his notebook. The other six stanzas were written out in his notebook with minor changes. The correct first stanza was supplied by Steve Gardham, who wrote down only the first stanza in visit to the Library in 2011. Later, a complete copy of the ballad was obtained from Steve Roud and sent to me in September 2016. The date of the broadside is unknown and Steve Roud estimated it was printed in the 1820s or 1830s. I'm dating it c. 1825.

H, "My Love A-Growing," was recited by Bell Robertson to Gavin Grieg about 1907 in New Pitsligo, Scotland[24]. It is probably taken from her mother, and is dated c.1856. Bell was born Feb. 1, 1841 at Denhead of Boyndlie, her father's croft. She got most of her ballads from her mother, Jean Gall, who was a folk-singer from Strichen (as James Nicol) and her mother's mother, Isobel Stephen, who also was a singer. This confirms that James Nicol's controversial "lifted up her fine Holland sark" stanza is traditional. Although Bell Robertson has reworked the "holland sark" line, Nicol's text rhymes and certainly fits better that the expurgated text:

But ae nicht afore that it grew dark

They walked doon by her father's park

And he proved the pleasure o' her heart

And she never thocht lang for growing. [Bell Robinson, 3rd stanza]

A-H and J, the earliest extant traditional versions, are all from Scotland. In my opinion, the ballad is about real events and real people from Scotland: The marriage of recently widowed Elizabeth Innes to a young college student, Alexander Brodie in 1635. It's also includes the sudden death of her first husband, John Urquhart, who died in 1634, and left a one year old son. Her father, Sir Robert Innes, played a part-- it was he who obliged her to marry young Brodie. That both these events were combined in the ballad without regard to the facts is understandable-- it even makes a more powerful version of the events.

Evidence contradicting the ballad's Scottish origin was presented by Sabine Baring-Gould[25] who suggested an English origin. Although Baring-Gould's scanty evidence of an English origin is unconvincing, the possible English origin was later imitated by Broadwood, Sharp (as editor of the 1905 edition of "Songs of the West"), A. L. Lloyd (notes to the 1959 Penguin Book) and others. Here now, is the ballad story.

* * * *

The Ballad Story

The ballad story itself is rather simple which is another reason why it was not included in Child's 305 English and Scottish Ballads (ten volumes from 1882-1899). Despite its simplicity the ballad explores one of the fundamental laws of life: we are either growing or dying. And when he was dead and in his grave--that put an end to his growing. When he was gone, the trees were still high, and the leaves were still green, and life goes on like a bubblin' stream and his love wishes he was -- still a-growin'.

O the trees thay are hie and the leaves thay ar green

The days are awa that I hae aften seen

The cauld winter nichts that I maun lye my lane

And my bonnie laddie's far, far fae me.

Above is last stanza of a Scot version from Elizabeth Macqueen, c. 1825 who helped her brother collect ballads for Andrew Crawfurd's collection of Scottish ballads and songs. In the ballad it's easy to understand the deep loss and sadness she feels all alone on a cold winter's night without her "bonnie laddie." She fell in love with the bonnie boy that she tried to reject saying to her father who arranged the marriage that she would rather have an old man with a staff than a young boy[26]:

"Father," she said, "You've done me much wrang,

You've wedded to a young, young man,

I'd have wedded ane wid staff in his han,

'Afore I had wedded a boy." [from The Glenbuchat Ballads, c. 1818]

Her father explains that his young boy is heir to his father estate and that someday he will be a man of wealth and power but he's still a-growing:

O dochter deir dochter I'v dune ye nae wrang

I'v marryit you to an Earl's only son

An whan his father dees he will be air o aw

And your bonnie lad daily growan. [also Elizabeth Macqueen, c. 1825]

The boy is in college and she suggests that he be sent back for another year so he can continue a-growing. She wants him to wear a ribbon to let the other girls know he's married:

O faither deir faither gin ye wad think it fit

To send him to the college anither yeir yit

I'd tye a grein ribban aw around his hat

To let the girls ken he is marryit [also Elizabeth Macqueen, c. 1825]

She decides to dress up in a disguise, because he's so young and their marriage is secret, to go see him at college[27]:

"I'll cut my yellow hair away by the root,

And I will clothe myself all in a boy's suit,

And to the college high, I will go afoot,

When my pretty lad so young still is growing." [from William Aggett, Chagford, around 1890]

At the college she watches him playing ball, and he's the fairest flower of all, and he's still a-growing. He can't tell anyone he's married at such a young age so he calls her his sister:

Then all the colligeners war playing at the ba',

But young Craigston was the flower of them a',

He said—" play on, my school fellows a';"

For I see my sister coming. [from James Nicol of Strichen, before 1822]

They took some time to sport and play:

Now down into the college park

They walked about till it was dark,

Then he lifted up her fine Holland sark,

And she had no reason to complain of his growing[28].

He was married at thirteen, the next year had a son, then suddenly he died and stopped a-growing:

But whan he was thirtene he was a marryit man

Whan he was fourtene he fatherit his auld son

Whan he was fifteen his grave was growan green

And that put an end to his growing.

She made him a holland shroud for his burial with great devotion:

She's made him shirts [a shroud] o' the Holland sae fine,

And wi' her ain hands she sewed the same;

And aye the tears came trickling down.

Saying, my bonnie laddie's lang o' growing. [Motherwell, c, 1819]

Even though her husband was dead, her bonnie son was lang o' growing. And the trees are still high and the leaves are still green, like the grass that grows o'er his grave has been. And she lies cold and alone on a winter's night--far, far from him:

O the trees thay are hie and the leaves thay ar green

The days are awa that I hae aften seen

The cauld winter nichts that I maun lye my lane

And my bonnie laddie's far, far fae me.

* * * *

The ballad had spread across the UK by the mid to late 1800s. It's dissemination was helped in part by the printing of broadside ballads titled similarly "My bonny lad(boy) is young, but he's growing" in London. Seven broadsides are found in the Bodleian collection (Broadside Ballads Online)-- most printed in London. For a more detailed examination of broadsides see Steve Gardham's report near the end of my headnotes. Burn's song was also printed as a broadside under the title, "My bonny lads growing" instead of Burn's title, "Lady Mary Ann." Burn's version was collected several times[29] showing that it too had entered tradition. Here's is the Such broadside, my I, dated circa 1863 (1863-1885), and printed in London[30]:

MY BONNY LAD IS YOUNG, BUT HE'S GROWING.

O, the trees that do grow high and the leaves that do grow green,

The days are gone and past, my love, that you and I have seen;

On a cold winter's night when you and I alone have been—

My bonny lad is young, but he's growing.

"O father, dear father, you to me much harm have done,

You married me to a boy, you know he is too young,"

"O daughter dear, if you will wait you'll quickly have a son,

And a lady you'll be while he's growing.

I will send him to the college for one year or two,

And perhaps in that time, my love, he then may do for you;

I'll buy him some nice ribbons to tie round his bonny waist, too,

And let the ladies know he's married."

She went to the college and looked over the wall,

She saw four-and-twenty gentlemen playing there at ball;

They would not let her go through, for her true love she did call,

Because he was a young man growing.

At the age of sixteen he was a married man,

At the age of seventeen she brought him forth a son,

At the age of eighteen the grass did grow over his gravestone,

Cruel death put an end to his growing.

I will make my love a shroud of the fine holland brown,

And all the time I'm making it the tears they shall run down,

Saying "Once I had a sweetheart, but now I have got none,

Farewell to thee, my bonny lad, for evermore."

O now my love is dead and in his grave doth lie,

The green grass grows over him so very high;

There I can sit and mourn until the day I die,

But I'll watch o'er his child while he's growing.

J, published in 1881 is taken from Traditional Ballad Airs, Volume 2 by Christie. His notes echo Maidment's 1824 notes and he quotes Spalding as well:

"Young Craigston" has been long a favourite with the populace in Buchan. The Air to which it was sung is here arranged. John Urquhart, called the Tutor of Cromarty, bought the Estate of Craigston, (Aberdeenshire.) The Ballad is supposed to have been composed on the marriage of his grandson with Elisabeth Innes, daughter of Sir Robert Innes of Innes, (Morayshire,) by whom he had a son [excerpt from Traditional Ballad Airs].

Baring-Gould's Versions

While Sabine Baring-Gould (1834-1924) was at Devon, he became interested in the ballad after collecting his first version from James Parsons[31] in 1888. Parson's version, albeit revised and combined with other traditional versions Baring-Gould collected, was published twice in "Songs of the West"-- first as an 8 stanza composite and then as a 13 stanza composite. These two versions as well as some of his song notes were subsequently reprinted[32].

Apparently[33] there were 7 published editions of "Songs of the West (also titled, Songs & Ballads of the West). In 1889 he published with H. Fleetwood Sheppard his first part of "Songs of the West" subtitled "A collection made from the mouths of the people by the Rev. S. Baring-Gould, M.A., and the Rev. H. Fleetwood Sheppard, M.A.". The 2nd through 4th parts were issued by 1891. Another edition with revised song notes and texts was issued in 1892 which covered all parts in a single edition--it was titled, "Songs and Ballads of the West." After that a similar 1895 edition was published. Then in 1905 a heavily revised edition, edited by Cecil Sharp, was published. Parson's 8 stanza composite appeared in two early editions with slightly different song notes while his 13 stanza composite appeared in 1905 with extensive notes.

Sabine Baring-Gould was the Squire and Parson of the parish of Lewtrenchard in West Devon. He was also a scholar, antiquarian, collector and a prolific author of both fiction and non-fiction: a man who was, in many ways, out of step with the rest of his generation[34]. Along with his zeal as a collector came his penchant for re-writing his collected ballads and songs. His recreations are captured in his notebooks online in which individual versions have been changed and made into composites. It's very difficult to know if any version he collected is authentic (written down exactly as heard)-- even the first texts.

I have studied his MSS in the Williams Library online[35] and there are over a dozen pages with five individual versions. One of the versions is the James Parsons/Matthew Baker compilation version which was published twice-- a long and a short version. The published versions also have stanzas from his other informants but the ballad is attributed to Parsons and Baker. All the versions appear to be collected between 1888 and 1890 and perhaps second Parsons' version in 1889 was also collected by music transcriber H. Fleetwood Sheppard-- although his text is not in Baring-Gould's notebooks. One compilation that was not published in Baring-Gould's "Songs and Ballads of the West" is called "Restoration of the Complete Ballad" and is 12 stanzas long. His longest published version is 13 stanzas but the texts are somewhat different throughout.

In addition to his collected and revised texts, Baring-Gould had two broadside texts in his notebooks, one is the standard "Such" text (Catnach and Sisley) as above and the other is very curious-- he says it's from "a volume of Scottish broadsides in British Library 1871f. dated 1750-1780"[36] "printed in Aberdeen probably." It is known that Baring Gould had access to the British Museum broadsides and looked at them for Child-- in the summer of 1890 he told Child he had searched all the broadsides in the Museum[37]. The dates of this Scottish broadside in his notebooks seem to be conjecture on his part-- over the 1750 date was written another date indicating that he corrected the date. In another copy he writes the date 1750- (18)28. In his "Songs of the West," 1891 notes he says, "But by far the truest form is that in an Aberdeen broadside; it will be found in the British Museum, under Ballads (1750—1840), Scottish, (Press mark, 1871 f.). The Scottish version has verses not in the English, and the English has a verse or two that are not in the Scottish." In his "Songs of the West," 1905 notes he calls the broadside "a very fairly complete one printed in Aberdeen at the end of last century or beginning of this." The Scottish broadside's actual reference number at the British library as 1871 f13 item 60a, which is the same (but missing the additional 13 item 60a) as Baring-Gould's reference. The title was given to me by Gardham as "My Bonny Laddie's Young" along with the first stanza-- showing that Baring-Gould's first stanza was written incorrectly[38]. Here is a copy of Scottish broadside, G, acquired by Gardham from Steve Roud which was found in the British Library:

"My Bonny Laddie's Young" -Scottish Broadside; 1871 f13 60a- British Library

1. The trees they are high and the leaves are green

The days they are awa that you and I have seen

The cauld winter nights I maun lie my lane,

My bonny laddie is young but he is growing[39].

2. Father, O father you have done me much wrong,

For you have married me to a lad that is young,

For he's scarce twelve and I am but thirteen

My bonny laddie's young but he's a growing.

3. O daughter, O daughter I have done you no wrong,

For I have married you to a rich lord's son,

And if you will wait, his bride you will be,

Your bonny laddie is young he is growing.

4. She sewed to him a shirt of Hollands fine,

And aye as she sew'd the tears they ran down,

And ay' as she sew'd the tears they ran down,

My bonny laddie is lang lang a growing.

5. Father, O father if you think it fit,

Weel send him to this high College another year yet,

And I'll cut of my yellow hair all above my brow,

And I'll go to the high College with my laddie now.

6. It happened on a day and a sun shiny day,

Here going to a green wood to sport and to play,

And what they did there I never will declare,

But she never complained on his growing.

7. At the age of thirteen he was a married man,

At the age of fourteen they had a young son,

At the age of fifteen his grave was growing green,

And that put and end to his growing.

By looking at his Baring-Gould's notebook it's clear that he didn't bother to take down the text from the British Library. Instead, he gave a line from one of his versions for the first line of Scottish broadside:

The trees they are so high, the leaves they are so green,

The day. . .[the rest of this stanza is missing]

This opening line which Baring-Gould used for many of this versions is slightly different than almost all other versions. Why he didn't copy the first stanza of the Scottish broadside is a mystery. The correct first stanza was given by Steve Gardham as:

The trees they are high and the leaves are green

The days they are awa that you and I have seen

The cauld winter nights I maun lie my lane,

My bonny laddie is young but he is growing[40].

Baring Gould also wrote down in his notebooks James Maidment's "The Laird of Craigstoun" and some of Maidment's notes about the origin of the ballad. Baring Gould tried, rather ineptly, to prove the ballad was in fact of English origin (previously covered). He believed (see his 1905 notes) that John Urquhart of Craigston inclusion in the ballad was fictitious- that he was inserted into an existing probably English ballad. Burns' version "Lady Mary Ann" is also found in two places in his notebooks- labeled once as Robert's ballad. There are six music transcription- two of them are not represented by texts, which apparently are missing.

Baring-Gould was sent on two short pages an Irish version sung by Mary O'Bryan of Abbey View, Cahir, Tipperary, that was learned from an old lady in West Clare in August, 1890, is copied down in his notebook and the original letter with her text is also there. It is one version that he appeared not to have tampered with. Baring-Gould simply re-wrote parts of the other versions- changing them at his whim and adding parts of different versions to improve the collected versions. Sometimes you can tell the original collected version but even these versions seem to be recreated somewhat. The William Aggett version appears to be authentic. But the version attributed to Mrs. Mason sung at his first lecture on 31 May 1890 is highly unusual and not found in his hand. I assume it was by Marianne Harriet Mason, 1845- 1932, who collected children's songs in Northumbia but also lived in Devon. Some of Mason's text is found in his long compilations-- here's a stanza:

4. At seventeen he wedded was, a father at eighteen,

At nineteen his face was white as milk, and then his grave was green;

And the daisies were outspread, and buttercups of gold,

O'er my pretty lad so young now ceased growing [old].

It seems to be a recreation-- probably by Mrs. Mason or Baring-Gould-- since nothing from tradition is like it. One text from Richard Broad, aged 71, of Herodsfoot, near S. Keyne, Cornwall[41] is missing in his notebooks-- the ballad may be there but it's not labeled. The controversial James Nicol stanza published in 1824 (see Maidment's version above) with the "lifting of the holland sark" was copied by Baring-Gould who left out the line and wrote "obscene" in the border. Baring-Gould, however, has recreated the famous stanza as taken from Scottish broadside and inserted into his text (see an edited version below- stanza 8 of his "Restoration"). Here are the versions with text I've found in his notebooks:

1. All the Trees they are so High- Mrs. Mason; from Words of Songs sung at first lecture "Ballad Music of the West of England" on 31 May, 1890 at the "Royal Institiution" on Albermarle St.

2. [The Bonny Boy]- Irish version sung by Mary O'Bryan of Abbey View, Cahir, Tipperary, learned from an old lady in West Clare in August, 1890. Sent to BG. MS

3. The Trees They are so High- James Parsons (with text from Matthew Baker) 12 stanzas MS

4. The Trees They are so high- compilation 8 stanzas (attributed to Parsons) Songs of the West

5. The Trees They are so high- compilation 13 stanzas (attributed to Parsons) Songs of the West

6. "Restoration of the Complete Ballad" compilation of 12 stanzas (see below) MS

7. [Growing]- Sept. 30, 1890 from William Aggett, aged 70, MS (his version has been recorded recently- see post on Mudcat Forum).

8. The Trees They are so High- Roger Hannaford of Lower Town, Widecombe, May, 1890 MS (two versions, one re-written by Baring-Gould)

"Restoration of the Complete Ballad" by Sabine Baring Gould c. 1891, mostly a traditional composite- part recreation.

1. All the trees they are so high! and the leaves they are so green,

The day is past and gone, sweet love, that you and I have seen.

It is a cold winter's night, you and I must lie alone:

For my pretty lad, you're young, but are growing.

2. O father, father dear, you've done me great wrong,

That you have married me unto a lad who's so young.

For he scarce is thirteen, O here I make my moan,

That my pretty lad's so young, tho' he's growing.

3. O daughter, daughter dear, no wrong to you is done,

For I have you married, unto a rich Lord's son.

And if that you will wait, until his bride shall be

For your pretty lad that's young, is still growing.

4. O father, father dear, if that you think it fit,

You'll send him to the college, another year yet.

Another year to wait, O the roaring of the sea!

Whilst my pretty lad that's young, still is growing.

5. In a garden as I walked, I heard them laugh and call;

There were four-and-twenty gallants there, playing at the ball;

O the rain in the north[42], here alone I must weep,

Whilst my pretty lad that's young, still is growing.

6. I listened in the garden, I looked o'er the wall;

Of five-and-twenty gallants there, my love exceeded all.

At the huffle of the gale, I turn and cannot sleep:

Whilst my pretty lad that's young, still is growing.

7. I'll cut my yellow hair, away above my brow,

I'll go unto the college and be with my laddie now,

I'll be with him sun and shower, his sports and studies share

Whilst my pretty lad that's young, still is growing.

8. It happened on a day and a sun shiny day[43],

We went into the green wood, that we might sport and play,

O the wind in the leaves, what then changed I'll not declare,

But I never said my lad was not growing.

9. I bound a bunch of ribbons green about my true love's waist,

To let the pretty ladies know they might no touch or taste,

For not taller that he grew, the sweeter still grew he

O my pretty lad's so young, tho' he's growing.

10. At thirteen he married was a father at fourteen,

At fifteen his face was white as milk, and then his grave was green;

And the daisies were outspread, and the buttercups of gold

O'er my pretty lad so young, now ceased growing.

11 O, I'll make my pretty love a shroud of holland fine,

And all the time I'm making it the tears run down the twine;

O alack! I had a true love, but now alas have none,

For my pretty lad so young, now ceased growing.

12. O now my love is dead I'll sit above his grave,

Where green the grasses grow and sweet the lilies wave,

And this for him I'll do, out lullabye for moan,

O'er his pretty little babe that's growing.

The influence of Baring-Gould's versions of "The Trees" and his song notes is still noticeable today. The Oxford Book of Ballads version by Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch is taken from Baring-Gould's collection- as is the version found in W.H. Auden's Book of Light Verse by W. H. Auden, 2004. Several researchers and performers of the ballad still refer to "the possible English origin" that Baring-Gould postulated in the 1880s. His evidence is unconvincing.

* * * *

A number of broadsides (for an example, see the Such broadside above) were printed in various location of England beginning in the 1860s. By the 1890s other versions besides Baring-Gould's began to be found. Frank Kidson found two fragments in Yorkshire[] while a complete version was collected by Lucy Broadwood from George Ede of Dunsfold, Surrey, in 1896. By the early 1900s "The Trees They Do Grow High" was described by Frank Kidson as "common all over the country." The ballad was subsequently found by the leading English collectors including, Lucy Broadwood, Cecil Sharp, H.E. Hammond, Clive Carey and Anne Gilchrist as well as composers Ralph Vaughan Williams, George Butterworth and Percy Granger[44]. It has been reported that Cecil Sharp has found 11 versions and multiple versions were found by the other collectors.

During the period of the two World Wars (1916-1945) ballad collecting was not an emphasis; so few versions were recorded then. In the 1950s Irish versions were collected from Seamus Ennis (who taught a version to Bob Copper), Margaret McGarvey and Pat Kelly[45] while the ballad was known by many of the Travellers singers including Caroline Hughes, May Bradley, Stanley Robertson, Nelson Penfold, Lizzie Higgins (from her father, Donald 'Donty' Higgins), Nelson Ridley, and Mary Ann Haynes. Higgins' version is aptly named "The College Boy" after thirteen-year-old college student Alexander Brodie enrolled in King's College in 1632 and 1633:

Oh father, dear father,

Pray what is this ye've done?

You have wed me to a college boy,

A boy that's far too young,

For he is only sixteen years

And I am twenty-one;

He's ma bonny, bonny boy

And he's growin.

Not only is he identified as "the college boy" but the ages of their marriage are nearly as the same ages of young Alexander Brodie and his older wife, Elizabeth.

I consider Higgins (born in 1929) a third generation singer from the point the ballad became popular in 1900 The second generation of singers born were after 1900 but before about 1920 included most of the the Travellers mentioned above and also George Dunn, Mary Ann Haynes, Fred Jordan and Walter Pardon. They were recorded in the 50s, 60s and 70s (and sometimes later) but learned their ballad in the 20s, 30s, and 40s. Higgins mother, Jeannie Robertson, would be a singer of the second generation after the ballad became popular. The texts of these singers tends to be fragmentary and the number of stanzas are often reduced. The sex stanza found in Nicol's 1824 text which was learned in Strichen (See: Maidment's "A North Countrie Garland") was ridiculed (called "rubbish") was modified in the 1800s[46] and by the early 1900s was largely forgotten. The name "Craigston (Craigstoun)" of the Scottish original has disappeared. Led by Baring-Gould and other English collectors, the historic events of the 1630s in Aberdeenshire have been dismissed when clearly the ballad is of Scottish origin[47]. The word "college" has become "cottage" or "church" -- while the "college wall" that she looked over to see him playing ball has become "castle wall" or "church wall."

To be fair to the singers of the 1900s, some of the same distinctions were never clear in early versions either perhaps because there were few ballads about "a college boy" and many about lords and "a castle wall." The events of the 1630s were confused by the historian Spalding in 1792 and ballad itself has combined the lives of both of Elizabeth Innes husbands-- so that the young "college boy" (Alexander Brodie) also has a son and dies the next year (John Urquhart).

With the ballad's popularity the story has been regulated with many versions by third generation (Lizzie Higgins, Fred Jordan, Joe Heaney, Ewan MacColl, Bert Lloyd) and fourth generation singers (Martin Carthy, and the folk revival singers of the 1960s) being nothing more than cover versions. It's become hard to tell which version is traditional since the 1950s. Joe Heaney, for example, doesn't mention his source-- I've included his version which is similar to the various "Bonny Boy" Irish versions and not much different than the English ones. A.L. Lloyd's 1951 version, recorded in London by Alan Lomax[48], is a compilation and is not included. MacColl's version "Lang A-Growing," although conveniently attributed to his mother and full of Scottish brogue, is not included because I consider it an arrangement even though his mother may have known some of the ballad. I've not included Martin Carthy's version for similar reasons. Many of the versions from the early 1900s on have harvested from such a popular vane that the ore has become muted and lost its luster. Still, I've tried to include all that are based on credible folk sources.

The 1907 version titled, The Trees They Do Grow High, that was collected by composer Ralph Vaughan Williams is remarkable because it was recorded on a wax cylinder and is one of the earliest recordings of a an English ballad. The second through through the fourth stanzas were recorded and it may be heard online here (copy and paste): http://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Ethnographic-wax-cylinders/025M-C0037X1583XX-0100V0

An Analysis of Ballad Stanzas

A. The Opening Stanza- Although some versions[49] do not have "'The Trees" opening stanza it is usually the opening stanza and this is an exploration of "The Trees" stanza. This stanza is mystical and the trees growing represents the seasonal passing of time-- as the years go by and have gone by. The setting is the future and the young wife is the singer who looks back and says, '"The days are gone that I have seen and better days would come again." She remembers the days when her bonny boy was growing:

Example A1 Craigston's Growing, the earliest complete ballad dating into the 1700s[50]:

1. The trees they are high and the leaves they are green

The days are awa that I hae seen

But better days I thought wou'd come again

An' my bonny, bonny boy was growin.

This is a simple but powerful opening, The listener wonders what the past days held, what went wrong and why she hopes for better days-- and who is the bonny boy who was growing. Because it's presented as if it's in the future and the events have already taken place. In this stanza, the last line seems to be her remembering when her bonny boy was growin. Her "bonny boy" would be expected to be her son. We later learn that it is her husband was a "bonny boy" who was growing. In this case it seems to be her remembering when her husband was young and growing. In other cases it seems to be about her son.

Example A2 is a similar Scottish "country" version[51] from Motherwell from the early 1800s:

1. The trees they are ivied, the leaves they are green,

The days are a' awa that I hae seen,

On the cauld winter nights I ha'e to lie my lane,

For my bonnie laddie's lang o' growing.

The difference is the third line introduces the a new twist--on cold winter night she must lie (alone) in her abode indicating a separation from her from her loved one. Perhaps she is alone because her lover is gone, or he's dead-- it's a mystery. Her bonnie laddie seems to be her son.

Example A3

6. O the trees thay are hie and the leaves thay ar green

The days are awa that I hae aften seen

The cauld winter nichts that I maun lye my lane

And my bonnie laddie's far far fae me [from Elizabeth Macqueen, C. 1828 Andrew Crawfurd's Collection]

Instead of being the first stanza viewed from the future, Macqueen's is the end stanza. The last line reveals the painful separation of her love being far, far from her. The "far, far" is quite far since he died in the previous stanza. Whether as a recapitulation or as an opening, this stanza is about her being alone after the death of her husband. His death is revealed in a line from the previous stanza, which appears similarly: "In his fourteenth year his grave grew green." The "my bonnie laddie's lang o' growing" line that follows would refer to her son "lang o' growing," since her husband is dead. Whether this was understood by the traditional singer is unknown. Here's how the standard opening stanza appears in England around 1900:

Example A4

1. "Oh! the trees are getting high, and the leaves are growing green;

The time is gone and past, my love, that you and I have seen!

Twas on a winters evening, as I sat all alone,

There I spied a bonny boy, young, but growing. [George Ede of Dunsfold, Surrey, in 1896.]

The time is past and gone, he has died and she is alone, she spies her bonny, bonny boy (her son). Here's another variant:

Example A5:

1. "The trees they do grow high, and the leaves they do grow green

The days are past and gone, my love, that you and I have seen,

On a cold winter's night my love, when we together have been,

So fare you well my bonny boy, forever." [from William Smith, Stoke Lacy, Herefordshire in Sept., 1907]

In this stanza, found either at the opening or the end, she bids farewell to her dead lover forever. After this the text goes into the Father-Daughter dialogue. There are very few independent stanzas that follow "The Trees" opening. Here's one from the earliest extant complete version:

2. I've been climbing a tree that's too high for me,

I've been seeking fruit thats nae growin.

I've been seeking hot water beneath the cold ice

An' against the stream I've been rowin. [from Craigston's Growing, pre-1818]

This rare filler stanza suggests the "difficulties" the young woman faces but does nothing to contribute to the ballad story.

B. The Dialogue between Father and Daughter- This dialogue starts with a stanza in which the daughter says her father has done her wrong for marrying her to a boy that's too young. In the next stanza (sometimes these are combined[52]) Her father replies that her young husband will heir to an estate and she will be a "lady" while he's growing. The dialogue frequently segues to the "College" stanzas. Here's the earliest example of the Father/Daughter dialogue from Craigston's growing:

Example B1

3. Father she said, you've done me much wrang

You've wedded to a young, young man

I'd have wedded ane wid staff in his han

'Afore I had wedded a boy.

4. O Daughter I did you no wrong

For the wedding you to o'er young a man

You've your tocher in your ain han'

An' your bonny love daily growin.

This version is unique for the daughter says she'd rather marry an old man with a cane in his hand than a young boy. Her father points out that he has a given her a tocher (a dowry) and she's ready to marry him. Usually the father says that the "over young" groom is a Lord and the heir of an estate as in this example from Motherwell's collection[53]:

Example B2

O father dear, you have done me great wrong,

You have wedded me to a boy that's too young,

He is scarce twelve, and I'm but thirteen,

And my bonnie laddie's lang o' growing.

O daughter dear, I have done you no wrong,

I have wedded you to a noble lord's son.

He'll be the lord, and ye'll wait on,

And your bonnie laddie's daily growing.

Alexander Brodie was the heir to the House of Brodie, one of the oldest clans in Scotland, when his father died in 1632. This was known by Sir Robert Innes when his daughter married Brodie in 1635. Alexander became Lord Brodie in 1649. Here's another Scottish version from Traditional Ballad Airs, Volume 2, by Christie, 1881:

Example B3

"Oh, father," said she, "you have done me wrong,

For ye've married me on a childe young man,

Ye've married me on a boy o'er young,

And the bonny boy is long, long a-growing."

"O daughter," said he, "I have done you no wrong,

For I've married you on an heritor of lan',

He's likewise possess'd of many bills and bonds,

And he will be aye daily growing.

C. The College Stanzas- although "collage" has been corrupted in some versions for "cottage" and "castle wall" instead of "college walls," her father offers to send her young husband back to college for a year or two to him to acquire additional skills and age so he would be a more suitable husband. Alexander Brodie was sent to England to go to school when he was just ten years old by his father[54]. According to Anderson Alumni p. 11, Brodie was admitted to King's College in 1631. After Brodie's father died in 1632 he returned to King's College for at least two years[55]. Even the earliest stanzas (before 1776) from Herd's MSS are the "college stanzas":

Example C1

She look’d o’er the castle[college] wa’,

She saw three lads play at the ba’,

O the youngest is the flower of a’!

But my love is lang o’ growing.

‘O father, gin ye think it fit,

We’ll send him to the college yet,

And tye a ribban round his hat,

And, father, I’ll gang wi him!’

There are many ballads about lords, knights and castles but not many about a "college boy." Here's a more recent version appropriately titled, "The College Boy" as sung by Lizzie Higgins (recorded by Peter Hall at the Aberdeen Folk Festival, 1973):

Example C2

Oh father, dear father,

Pray what is this ye've done?

You have wed me to a college boy,

A boy that's far too young,

For he is only sixteen years

And I am twenty-one;

He's ma bonny, bonny boy

And he's growin.

As we were going through college

When some boys were playin' ball,

When there I saw my own true love,

The fairest of them all,

When there I saw my own true love,

The fairest of them all;

He's ma bonny, bonny boy

And he's growin.

Here's a standard version with a short chorus collected by Lucy Broadwood from Mrs. Joiner of Chiswell Green, Hertfordshire on Sept. 7th, 1914.

Example C3

3 I'll send your love to college, all for a year or two,

And then in the meantime he will do for you;

I'll buy him white ribbons[1], tie them round his bonny waist,

To let the ladies know that he's married."

CHORUS: Married, married, to let the ladies, etc.

4 I went up to the college, and I looked all over the wall,

Saw four and twenty gentlemen playing at bat and ball,

I called for my own love, but they would not let him come,

All because he was a young boy, and growing.

CHORUS: Growing, growing, all because, etc.

One additional "college" stanza is sometimes found in which she disguises herself as a boy and goes to visit him at college:

Example C4

I'll cast my yellow hair away by the root

And I will clothe myself all in a school boy's suit

And to the college, I will go a-foot

Whilst my pretty lad so young still is growing. [collected by Sabine Baring Gould on Sept. 30, 1890 from "William Aggett, aged 70, crippled and infirm, Chagford.]

D. The Sex Stanza- This stanza was first collected from James Nicol of Strichen before 1822 and was published in A North Countrie Garland, 1824, edited by James Maidment. It was called "rubbish[55]" and was edited out of C.K. Sharpe's version in 1839. Apparently the play on words was too graphic:

Example D1

Now down into the college park

They walked about till it was dark,

Then he lifted up her fine Holland sark,

And she had no reason to complain

Of his growing, growing, &c.

A modified version, also from Stichen comes from Bell Robertson, learned circa 1856 probably from her mother:

Example D2

But ae nicht afore that it grew dark

They walked doon by her father's park

And he proved the pleasure o' her heart

And she never thocht lang for growing[56].

Other modified versions are similar to the stanza found in a Scottish broadside printed circa 1820s:

Example D3

6. It happened on a day and a sun shiny day,

Here going to a green wood to sport and to play,

And what they did there I never will declare,

But she never complained on his growing.

Sabine Baring-Gould included this stanza in some of his compilations.

E. The Age and Death Stanza- Although the ages of the couple when they marry are occasionally given in an earlier stanza (see, foe example, C2), the age of his marriage, his age when he became a father and his age of death are cleverly given in three successive lines in this stanza:

Example E1

At the age of thirteen he was a married man,

At the age of fourteen he had a young son,

At the age of fifteen his grave was growing green,

And that put and end to his growing[57].

The last line is very powerful since in previous stanzas it was consistently: "For my bonnie laddie's lang o' growing." His age varies in different versions and he usually becomes a married man from twelve to sixteen years of age. In Bell Robertson's version[58] he's only 7 years old!!!

The following elaborate stanza was collected by Baring-Gould who revised many of the versions he collected. Parsons was revisited in 1889 and added two stanzas. According to a printed version from one of Baring-Gould's ballad programs- this stanza was attributed to a Mrs. Mason. Whatever the source-- it doesn't seem traditional:

Example E2

6. At fourteen he wedded was, a father at fifteen,

And then his face was white as milk, and then his grave was green;

And the daisies there were outspread, and the buttercups of gold

Ah! my lad who was so young, hath ceased growing. [attributed[59] to James Parsons of Lew Down, Sept., 1888. Collected by Baring-Gould.]

F. "The Shroud of holland fine" stanza. After her husband dies she knits him a shroud of holland fine. Shroud in some cases has become "shirt" or some garment. "Holland," a type of fabric, has become in Vermont[60]: "finest of lawn" instead of the "finest holland." The first appearance of this stanza was from Motherwell who collected when he was at Paisley about 1820:

Example F1:

She's made him shirts[61] o' the holland sae fine,

And wi' her ain hands she sewed the same;

And aye the tears came trickling down.

Saying, my bonnie laddie's lang o' growing.

Occasionally this stanza precedes the "death" stanza where it makes no sense-- such is the case in The Scottish broadside (see above) and many other versions. Here's another version:

Example F2:

5 She made her love a shroud of the holland, O so fine,

And every stitch she put in it, the tears came trinkling down.

O once I had a sweetheart, but now I have got never a one:

So fare you well my own true Love, forever. [from Mr. Harry Richards, at Curry Rivell, July 28th, 1904. Collected by Sharp.]

Although this stanza is only present in less than half the complete versions, I consider it part of the ur-ballad since it was Scottish and found in early version.

Sometimes the "Shroud stanza" is the last stanza:

Example F3

6. "Then I'll make my love a shroud of the best of holland brown,

And while that I am making it the tears they shall run down;

For once I had a true love, but now I've got never a one,

But I'll watch all over his son, whilst he's growing." [from William Smith, Stoke Lacy, Herefordshire in Sept., 1907. Collected by George Butterworth.]

Here's another Shroud end stanza, from the earliest extant Irish version:

Example F4

6. I'll weave my love shroud of the immortal brown,

And the while that I do weave it the tears will trickle down,

I will weep and I will wail till the day that I die,

And I'll rear his bonny boy, whilst he's growing. [from Mary O'Bryan of Abbey View, Cahir, Tipperary, learned from an old lady in West Clare in August, 1890.]

G. The Ending Stanzas. Examples E and F are both "ending" stanzas. As discussed in "A. The Opening Stanza," the "trees stanza" also appears as an ending. In Harry Richard's version[62] it is the opening and ending stanza:

Example G1

6. The trees they do grow high, and the leaves they do grow green;

But the time is gone and past, my Love, that you and I have seen.

It's a cold winter's night, my love, when you and I must bide alone,

So fare you well my own true love, for ever.

Only the last line is changed from Richard's opening stanza which ends: "The bonny lad was young, but a-growing." This gives symmetry to the ballad. Another example of the "trees" stanza found both as an opening and as an ending stanza is Craigston's Growing:

Example G2

8. The trees are high & the leaves are green

The days are awa that I hae seen

An' anither may be welcome where I hae happy been

Tak up young Craigston's growin.

The following ending stanza appears to be the creation of a broadside writer and, in my opinion, is not traditional. Here's the ending stanza from the Such broadside, dated circa 1863 (1863-1885), and printed in London:

Example G3

O now my love is dead and in his grave doth lie,

The green grass grows over him so very high;

There I can sit and mourn until the day I die,

But I'll watch o'er his child while he's growing.

This ending is found in several complete versions, for example the version sung by Mrs. Joiner of Chiswell Green, Hertfordshire,, Sept. 7th, 1914. Versions that have this stanza may be based on print. One last ending stanza has been found in some Irish versions and one English version. it's a floating stanza found in other songs and ballads. Here's Harry Cox's version:

Example G4

Oh, come all you pretty fair young maidens listen unto to me

And never build your nest in the dark of any tree

The green leaves they will wither, the roots they will decay,

And my bonny lad is young and he is growin'.

* * * *

Conclusion: Cruel death put an end to his growing!

Whether the "cruel death" line is sung by James Nicol of Strichen around 1822 or Joan Baez or a lesser known traditional singer from Carna named Seán 'ac Dhonncha, it remains one of the most powerful lines in all balladry:

At the age of sixteen he was a married man,

At the age of seventeen she brought him forth a son,

At the age of eighteen the grass did grow over his gravestone,

Cruel death put an end to his growing[63].

I wonder why this little ballad was not included by F. J. Child in his The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, a ten volume collection of 305 ballads published between 1882-1898. What did Child know about "The Trees" and why was it not one of the 305 ballads included in ESPB?

Obviously Child's ultimate decision will never be known but exploring the answer may provide an insight of how the ballad was viewed in the latter half of the 19th century. In 1935 S. B. Hustvedt wrote, "While Francis James Child was preparing the manuscript for the publication of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Svend Grundtvig sent to him, in the form of enclosures with letters dated August 25, 1877 and January 29, 1880, a numbered list of English and Scottish ballads arranged in the order which Grundtvig, at Child's earlier request, meant to propose as a proper sequence for publication[64]."