The Berkshire Tragedy (Wexford Tragedy; Cruel Miller; Knoxville Girl) Roud 263; Laws P35

Additional titles include: Hanged I Shall Be; Bloody Miller; The Oxford Girl; Knoxville Girl; Ekefield Town; Ickfield Town; Wexford Town; The Butcher Boy; Lexington Murder; The Prentice Boy; Lexington Miller; Wexford Tragedy; Lexington Girl; Cruel Miller; Wexford Lass; The Miller's Apprentice, or The Oxford Tragedy; Expert Girl; Export Girl; Noel Girl; Nell Crospie/Crospey; Flora Dean; Waco Girl

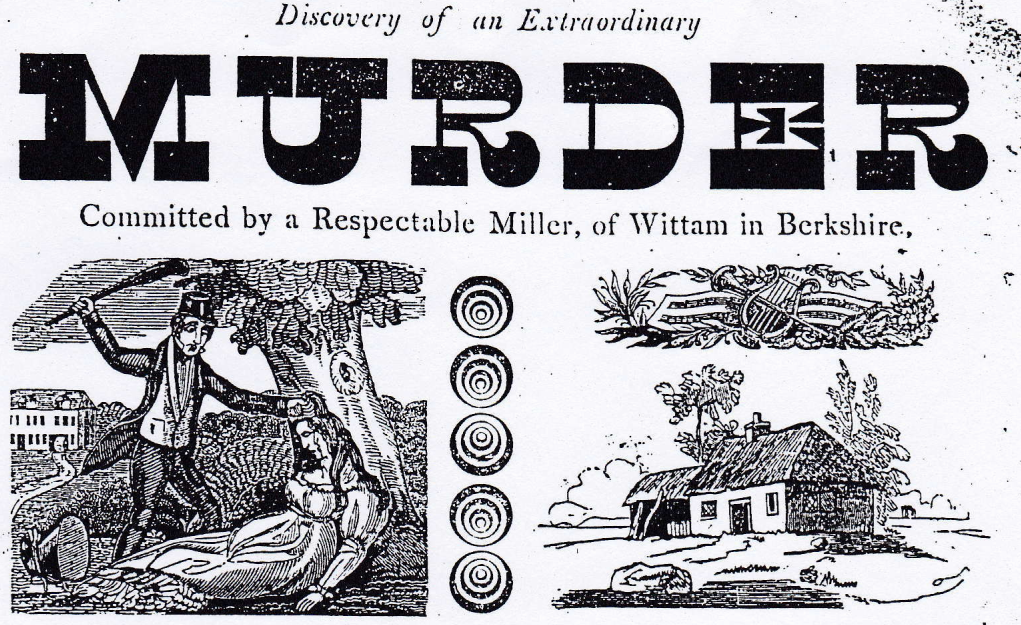

Woodcuts from the Catnach broadside of "The Berkshire Tragedy" c. 1820

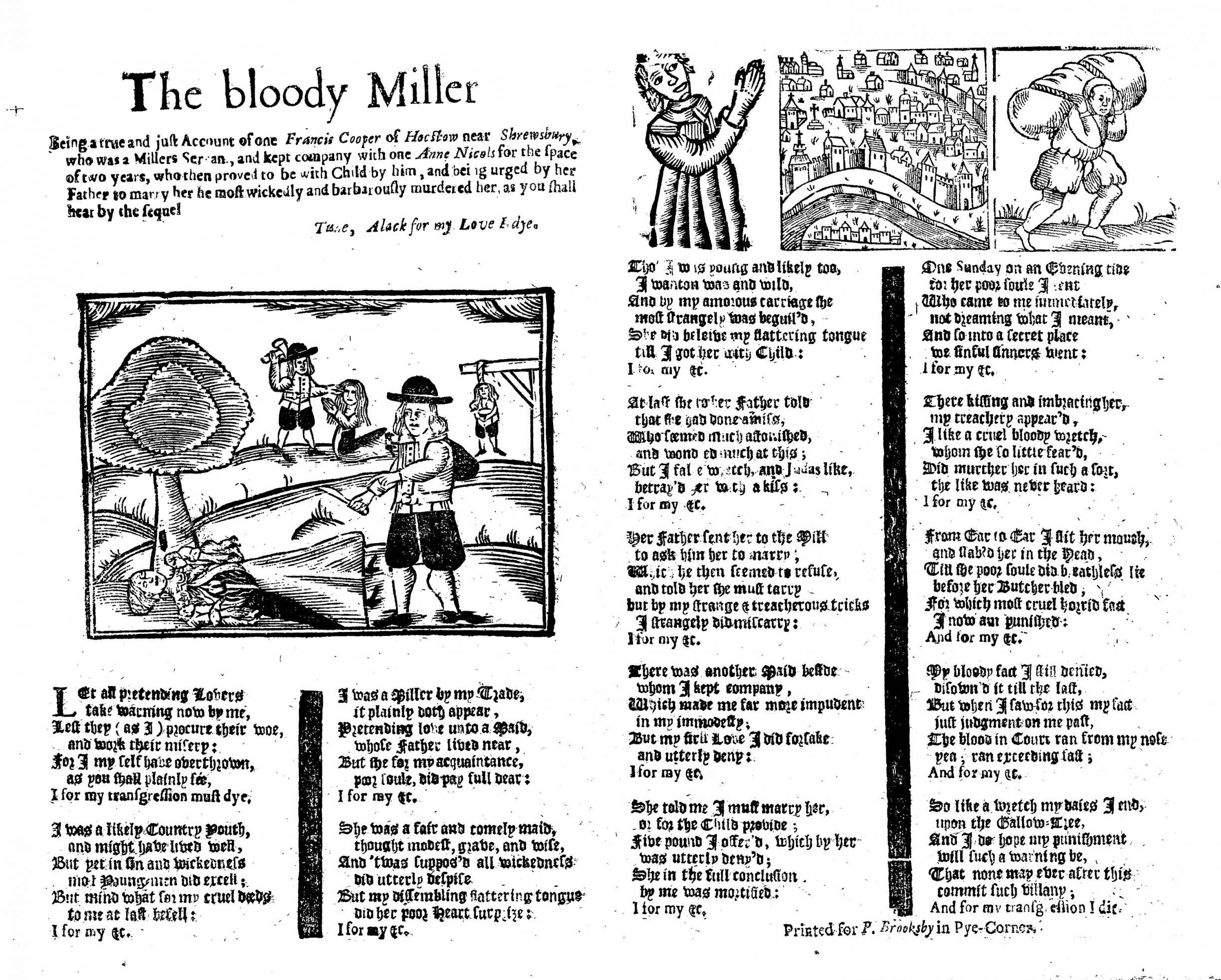

Bloody Miller (possible model)

A. "The Bloody Miller" printed by P. Brooksby in Pye Corner, London, shortly after the murder on Feb. 10, 1684 (The Pepys Ballads, volume 2, p156). Subtitled, Being a true and just account of one Francis Cooper of Hocstow near Shrewsbury, who was a Millers Servant, and kept company with one Anne Nicols for the space of two years, who then proved to be with child by him, and being urged by her father to marry her he most wickedly and barbarously murdered her, as you shall hear by the sequel. Tune: Alack for my Love I dye.

Berkshire Tragedy/Whittingham Miller broadsides

Ba. "The Berkshire Trgedy; Or, the Wittam Miller: with an Account of His Murdering His Sweetheart," dated c. 1700 in Bodleian, ESTC: T204012; Antiq c. E9 (125) (dated c.1730 Pettitt); and see: Roxburghe (dated c. 1700 Ebsworth). Also John Cluer/Dicey as printed and sold at No. 4, Aldermary Churchyard c. 1730s. Unknown printing (ref. Google Books), no printer named, dated 1720.

Bb. “The BERKSHIRE TRAGEDY, OR, The WHITTAM Miller, Who most barbarously murder’d his Sweet-heart: With his whole Trial, Examination and Confession; and his last dying Words at the Place of Execution,” dated 1744; from a Scottish chapbook printed by Robert Drummond for John Keel, Edinburgh. It concludes, “The last dying words and confession of John Mauge, a Miller, who was executed at Reading in Berkshire, on Saturday the 20th of last month, for the barbarous murder of Anne Knite, his sweet-heart.”

Bc. "The Berkshire Tragedy; Or, The Wittam Miller. With an Account of his Murdering his Sweetheart. To the Tune of, The Oxfordshire Tragedy," c.1750’s and 60’s. London: Printed and sold at Sympson's Printing-Office, in Stonecutter Street, Fleet Market. n.d. given.

Bd. "THE WITTHAM-MILLER, Being an Account of his Murdering his Sweetheart, &c. OR THE BERKSHIRE TRAGEDY." c. 1790 as printed and Sold by D Wrighton [sic] 86 Snow Hill, Birmingham.

Be. "The tragical ballad of the miller of Whittingham Mill. Or, a warning to all young men and maidens." Glasgow, printed by J. & M. Robertson, 1800. Also in chapbook, "The History, Witty Questions and Answers, of that noted Philosopher, the Miller of Whittingham Mill, and Betty Puslem his wife." Published Edinburgh, 1793.

Bf. "Discovery of an Extraordinary MURDER Committed by a Respectable Miller, of Wittam in Berkshire," (see woodcuts at top of this page), J. Catnach, Printer, 2 & 3, Monmouth-court, 7 Dials. c. 1825.

Wexford Tragedy (chapbook) Archaic Wexford Reductions

Ca. "The Wexford Tragedy Or, The False Lover" from a chapbook printed by [Yellich and] T. Johnston 1818 Falkirk, Scotland. 8 1/2 stanzas or 17 divided stanzas. Chapbookis titled: "The freemason's song; to which are added, The Wexford Tragedy Or, The False Lover and My Friend and Pitcher." Printed for Freemason[s], 1818. From: Bodleian's Firth collection, catalogue no. Firth f.75 (23).

Cb. "The Worcester Tragedy." Collected by Kenneth Peacock in 1959 from Mrs Charlotte Decker [1884-1967] of Parson's Pond, NL. Published in Songs Of The Newfoundland Outports, Volume 2, pp.638-639, by the National Museum of Canada (1965).

The Four "Cruel Miller" broadsides

Da. "The Cruel Miller, or, Love and Murder" broadside dated 1813–38 London: J. Catnach, 18 stanzas [This is not "Love and Murder" or "Polly's Love" a shortened broadside version of Gosport Tragedy].

Db. "Bloody Miller" broadside dated 1789-1820 Imprint: Thompson, Printer, no. 156, Dale-Street, Liverpool [This is not A, also Bloody Miller or Ic, The Bloody Miller].

Dc. "The Cruel Miller," broadside dated 1819-1844; Pitts, Printer, 6, Great St. Andrew Street, 7 Dials, London.

Dd. "False-Hearted Miller," broadside 1815-1855 by Pollock, J.K. printer; North Shields.

Lexington Miller broadside

Ea. "The Lexington Miller" broadside dated 1829-1831, Sold wholesale and retail, by L. Deming, no. 1, Market Square, Boston. Also printed in The Journal of American Folklore (Vol. 42, No. 165, pp. 247-253), 1929.

Eb. "The Lexington Tragedy," sung by Alonzo Lewis on York, Maine as recorded by Helen Flanders on October 1, 1948.

Scottish Traditional- "Butcher Boy" Reductions

Fa. "The Butcher Boy" sung by Sam Davidson 1863–1951 of Auchedly, Tarves Aberdeen; a farmer and the owner of North Seat Farm and well known singer who learned ballads from his farm hands. Collected by Gavin Greig (version D) c. 1908.

Fb. "The Butcher Boy" sung by Annie Shirer (b. 1873) of Kininmonth who got her ballads from her father and uncle Kenneth Shirer. Collected by Gavin Grieg (version E), c. 1908.

Fc. "The Butcher's Boy" As sung by Miss Kate Mitchell, collected by Gavin Grieg (A), c. 1910.

Fd. "The Butcher Boy"- sung by Charles Fiddes Reid (b. 1907) of Crimond, Aberdeenshire as recorded by Hamish Henderson and Prof. James Porter in 1972. Charles Reid heard this song from his grandmother when he was about eight, on holiday at Auchnagatt.

Fe. "The Butcher Boy" sung by Jeannie Robertson recorded by Hamish Henderson in 1953. Jeannie Robertson learned this from a woman friend around 25 years previously.

Ff. "The Butcher's Boy" sung by Elizabeth Stewart (c. 1955)as learned from her mother Jean (c1945), with minor changes.

Fg. "The Butcher Boy" John Argo of Ellon, Aberdeenshire. Recorded by Hamish Henderson in 1952. John Argo heard this song from his mother while she was nursing his baby brother.

Fh. "The Butcher's Boy" sung by Andrew Robbie of Strichen, Aberdeenshire. Recorded in 1960 by Prof. Kenneth Goldstein

English Traditional ballads- "Various" reductions

Ga. "The Miller's Apprentice," sung by William Spearing of Somerset as collected by Cecil Sharp in 1904. From Sharp's MS and "Miller's Apprentice" is Sharp's master title.

Gb. "Prentice Boy" sung by Joseph Elliot of Dorsst in 1905. From Henry Hammond Manuscript Collection (HAM/2/8/20) with music. Also in Songs of Crime and Prison Life by Lucy E. Broadwood and A. G. Gilchrist; Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Vol. 7, No. 27 (Dec., 1923), pp. 41-49.

Gc. "Hanged I Shall Be," sung by David Marlow of Basingstoke, Hampshire recorded by George B. Gardiner, 1906. From the George Gardiner Manuscript Collection (GG/1/10/553). Originally titled: My Parents Reared me Tenderly (Hanged I shall Be).

Gd. "Ferry Hinksey Town" sung by George Hicks of Arlington, Gloucestershire and an old woman. Collected by Alfred Williams, published 3rd June, 1916 in Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, p 3, Part 32, No. 4. See also Williams MS and WSRO transcription.

Ge. "Hanged I Shall Be," sung by 'Sheppard' Taylor of Hickling, Norfolk in October 1921. Collected and arranged by E.J. Moeran, The Journal of the Folk Song Society, vol.VII issue 26, 1922 (p.23).

Gf. "Oxford Girl," sung by Phoebe Smith of Suffex, July 8, 1956 as recorded by Peter Kennedy, London; BBC Sound Archives 23099. Also `Black Velvet Band;' and 'I am a Romany' Topic TSCD 673T 'Good People Take Warning', CD1 track 18. Published in Folksongs of Britain and Ireland. Ed. Peter Kennedy. London, 1975, p. 713, No. 327.

Gg. "Ekefield Town," sung by Harry Cox of Catfield in Norfolk; recorded by Mervyn Plunkett in 1960.

Gh. "Waxford Town," sung by Mary Ann Haynes of Brighton, in 1972; recorded by Mike Yates.

Irish Traditional ballads

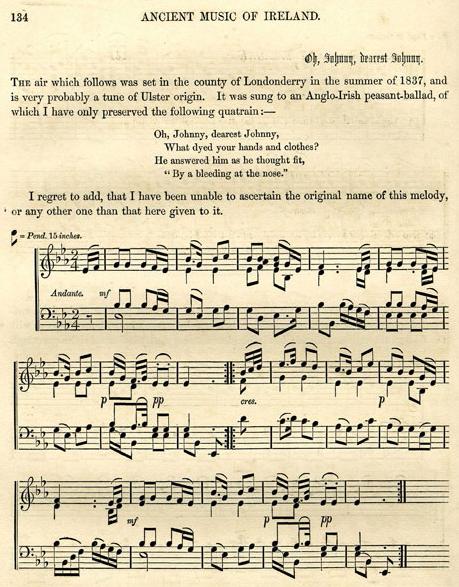

Ha. "Oh Johnny, Dearest Johnny" is an air with a single stanza of text collected in Londonderry in the summer of 1837. Petrie calls this an Anglo-Irish peasant ballad.

Hb. "Dublin City" sung by Mary Doran (tinker), Belfast, recorded and collected by Peter Kennedy in 1952.

Hc. "Town of Linsborough" sung by an Irish traveller in England named Mary Delaney in the early 1970s.

Older American Traditional- Berkshire/Oxford and Lexington Reductions

Ia. ["Wittenham Miller"] "The Lexington Girl." Recorded by Mrs. Henry from the singing of Mrs. Samuel Harmon (b. about 1870), Cade's Cove, Blount County, Tennessee, August 13, 1930, who says that she has "known the song all her life." From Mellinger Henry's "Folk Songs from the Southern Highlands," J. J. Augustin, 1938.

Ib. ["Lexington Girl."] From Mrs. Mary Boney, Perrysville, Ohio, from Eddy, "Ballads and Songs from Ohio," 1939, version C.

Ic. "Bloody Miller" from a MS by Jane Eller of North Carolina in 1901 Abrams A

Id. "Bloody Miller or Murdering Miller." Contributed by I. G. Greer of Boone, Watauga county, NC in 1915 or 1916. Text from

Abrams Collection/Greer Collection- Lyric Variant 4.

Ie. "The Oxfordshire Lass," collected in 1949 by Jean Ritchie, as sung by Jason Ritchie who learned it from the Williams family. From an article "Living is Collecting" by Jean Ritchie in "An Appalachian symposium: essays written in honor of Cratis D. Williams" by Jerry Wayne Williamson- 1977; p. 195, 196.

American Traditional- "Lexington Murder" Reduction

Ja. "The Lexington Girl." Sung by Miss Mary Riddle, North Fork Road, Black Mountain, North Carolina, 1925. From Mellinger Henry's "Folk Songs from the Southern Highlands," J.J. Augustin, 1938; first published in the 1929 JAFL article "Lexington Girl."

Jb. "My Confession." Contributed by Miss Sylvia Vaughan, of Oakland City, Indiana. Gibson County. Secured from her mother, Mrs. Hiram Vaughan. March 5, 1935. From: Brewster's "Ballads and Songs of Indiana; Indiana University Publications, Folklore Series," 1940.

Jc. "Lexington Murder." Sung by Fields Ward of Galax, Va., recorded in 1937; from Our Singing Country by Alan Lomax, 1941.

Jd. "Lexington Murder." Sung by Nora Hicks, taken down by Addie Hicks c. 1937 From Abrams Collection; no date, typed MS. This standard version (from the late 1800s) was copied by Nora's daughter Addie for Edith Walker, a student collector for Abrams.

Je. "The Lexington Murder." Collected by Mrs. Zebulon Baird Vance near Black Mountain, Buncombe county, and received by the Society in April 1915. From: Brown Collection of NC Folklore; volumes 2, 1952.

Jf. "The Lexington Murder," c. 1939. Sung by anonymous singer. Recorded, but no date or place given. The text of this version is a combination of Brown versions A and F. From the Brown Collection of NC Folklore, volume 4, 1956.

Jg. "Lexington Murder." Sung by Mrs. Nilla Lancaster of Wayne County, NC; from the Brown Collection of NC Folklore; volumes 2, 1952.

Jh. "Lexington Miller," sung by Martha Hodges of NC in 1931. Given to W. Amos Abrams in 1939 by Imogene Norris, "to whom the ballad was sung 8 years previously by Mrs. Martha Hodges."

Ji. "Lexington Murder." Sung by Mrs. Susie Wasson of Springdale, Arkansas on August 8, 1959 Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 284, Item 4. Collected by Iola Stone for Mary Celestia Parler. Transcribed by Iola Stone.

Jj. "Lexington Girl," sung by Lillie and Pearl Steele of Hamilton, Ohio, with banjo by Pete Steele on March 30, 1938. Recorded by Alan Lomax. Learned in Butler County, Kentucky from Clara Boyd (?) known for 23 years.

Jk. "The Lexington Murder," sung by Wesley Hargis of Raleigh, North Carolina in 1934. Collected by John A. & Alan Lomax. New World NW 245 (`Oh My Little Darling: Folk Song Types').

Jl. "Lexington Murder," sung by Abie Shepherd of Bryson City, N. C. in summer of 1923. Collected by Isabel Gordon Carter.

Some Songs and Ballads from Tennessee and North Carolina by Isabel Gordon Carter; The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 46, No. 179 (Jan. - Mar., 1933), pp. 22-50.

Jm. "Lexington Murder," as sung by W. D. Collins of Missouri, Wyoming, and Oklahoma about 1953. W.D. Collins (1893-1976), a stockman, community song leader, square dance caller, cowboy, and Baptist preacher. From "Ideology and Folksong Re-creation in the Home-recorded Repertoire of W. D. Collins" by Melinda S Collins.

Jo. "One Saturday Night," sung by Colon Keel with guitar in Raiford, Florida on June 3, 1939 (recorded by John Avery Lomax, Ruby T. Lomax)

Jp. "Never Let the Devil Get The Upper Hand Of You," as sung by the Carter Family of Virginia, collected by A.P. Carter, recorded 1937 on Decca recording 5479, New York , NY.

Jq. "The Old Mill," sung by Mr. Lair to his daughter about 1890. Payne "Songs and Ballads Grave and Gay" and also Dobie, Texas and Southwestern Lore, p. 213; Texas.

Jr. "City of Pineville," sung by Mrs. Lee Stevens of White Rock MO, Aug. 10, 1927. Randolph A; Randolph, Ozark Folksongs; 4 vols. 1946-50.

Js. "The Mill Boy," sung by Mrs. Dan McCracken (daughter of informant) Fayetteville, Ark. (guitar) March 3, 1950. Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 22 Item 3.

Jt. Lexaton Murder- Frank Joy (NY) pre-1963 REC

Ju. "The Lexington Girl," sung by Fleecy Fox, Arkansas, 1963 Wolf C

Jv. "Prentice Boy" sung by Marybird McAllister of Brown's Cove, VA in 1958, collected by Barry Foss. From "Anglo-American Folksong Style" by Abrahams and Foss, 1968.

Jw. "The Printer's Boy"- Communicated by Miss Sylvia Vaughan, of Oakland City, Indiana. Gibson County. From Southern Folklore Quarterly - Volumes 2-3 - pages 208-209, 1938.

American Traditional- Nell Cropsey Murder- "Lexington Murder" Reduction

Ka. "Nell Cropsey," sung by John Squire Chappell of Tyner, NC in 1912. [Lexington Murder]

Kb. "Nellie Crospie," sung by Betty Bostic of Mooresboro, NC March 5, 1938 as learned from her grandmother; Abrams. See also her grandmother's version 'Lexington Murder,' as sung by Mrs. G. L. Bostic. [Lexington Murder]

Kc. "Nell Cropsey" sung by Grace Zurawicki (NC) 1974 From North Carolina Folklore Journal - Volume 22 - Page 52, 1974. [Lexington Murder].

Mostly American Traditional- Standard "Wexford" Reduction

La. "Wexford Murder," sung by Walter Church c.1900. From Garners Gay, EFDS Publications, 1967, p.40. This is an Irish-Canadian version learned by an Englishman.

Lb. "The Tragedy." Communicated by Miss Marie Rennar, Morgantown, Monongalia County; obtained from Mrs. Dayton Wiles, who learned it from her mother, who lived many years in the mountains near Rowlesburg, Preston County. From Cox, "Folk-Songs Of The South," p. 311-313, 1925.

Lc. "Johnny McDowell." Contributed by Miss Snoah McCourt, Orndoff, Webster County, May, 1916.

Ld. "Waterford Town- sung by Daniel Brown of River John, Nova Scotia. Roy Mackenzie's "Ballads and Sea Songs from Nova Scotia," 1928; pp. 293-294.

Le. "The Wexford Girl," sung by Ethel Findlater of Birsay and Harray, Orkney. Recorded by Alan Buford, Elizabeth Neilsen. Ethel Findlater learned this song from her mother many years before. Since it's obviously from North America it's likely that since Orkney's industry is fishing that "the Orkney version came back from the Eastern Seaboard (of Canada). Orkney men were great sailors and many went to the fishing off Newfoundland and of course went whaling to Baffin Bay."

Lf. "Waxford Girl," sung by Mrs. Robertson of Ohio 1939 Eddy A from "Ballads and Songs from Ohio," 1939. Most version are from the 1920s, a version of her The Murdered Girl ballads.

Lg. "The Expert Girl" was contributed by Miss Lucile Morris, Springfield, Mo., Feb. 22, 1933. From: Randolph, Ozark Folksongs; 4 vols. 1946-50; reprinted Columbia, 1980, II, 92.

Lh. "The Waxford Girl." Sung in 1935 by Mrs Allan McClellan, near Bad Axe. Ballads and Songs of Southern Michigan by Chickering and Gardner 1939.

Li. "Wexford Girl" -sung by John James of Trespassy, NL. Recorded by MacEdward Leach in 1951

Lj. "Wexford Girl," sung by Irish-American emigrant John W. Green (1871-1963) of Saint James, Beaver Island, MI, in 1938.

Library of Congress recording by AFC 1939/007: AFS 02282A made Alan Lomax in 1938.

Lk. "Waxford Girl." - sung by Alice Mancour of Bellows Falls, Vermont on 10-17-1942. Partial transcription From a recording in the Helen Hartness Flanders Ballad Collection at Middlebury College Special Collections & Archives. Classification #: LAP35. Track 14.

Ll. "Waxford Girl," sung by Lily Delorme of Hardscrabble, Cadyville (NY). Dated June 18, 1942. Many of Delorme's ballads date to her childhood and to her father from Vermont in the early to mid-1800s. Helen Hartness Flanders Ballad Collection at Middlebury College Special Collections & Archives. Classification #: LAP35. Track 09.

Lm. "Wexford Girl," recitation by Eldin Colsie at Stacyville (Me.) dated 1941. Flanders D; from recording in Helen Hartness Flanders Ballad Collection at Middlebury College Special Collections & Archives. Classification #: LAP35. Track 08b.

Ln. "Waxford Girl," sung by John Galusha of Minerva, New York, 1941. Warners' "Traditional American Folk Songs" 1984.

Lo. "The Waxford Girl." Sung by Mrs. Pearl Brewer Pocahontas, Arkansas August 28, 1958. Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 295, Item 7. Collected and transcribed by Mary Celestia Parler.

Lp. "The Wexford Girl." Collected by Kenneth Peacock in 1958 from Arthur Nicolle [1900-1971] of Rocky Harbour, NL (Kenneth Peacock - Variant A) Songs Of The Newfoundland Outports, Volume 2, pp.634-635, by the National Museum of Canada (1965).

Lq. "Wexford Lass," sung by Frank Ramsay of New Brunswick in 1947 Manny/Wilson. From: Songs of the Miramichi by Manny and Wilson 1968.

Lr. "The Wexford City." Collected by Kenneth Peacock in 1951 from Michael (Mike) A Kent [1904-1997] of Cape Broyle, NL.

Songs Of The Newfoundland Outports, Volume 2, pp.634-635, by the National Museum of Canada (1965).

Ls. "The Waxweed Girl." As sung by Mr. David Pricket, Clifty, Arkansas on January 19, 1958. Mr. David Pricket learned this song from his father. Max Hunter Folk Song Collection Cat. #0008 (MFH #670).

Lt. "The Waxfort Girl," sung by Mrs. Donia Cooper of West Fork, Ark. on August 14, 1959. Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 287-288, Item 19. Collected by Mary Celestia Parler.

Lu. "Waxford Lass." Sung by Dellas Macdonald of Glenwood, NB in 1961. The Folklore Historian, Volume 14; "How the Apples Got In?' by Ives; also see Ives, Wilmot MacDonald at the Miramichi Folksong Festival- page 51.

Lv. "Waxford Lass." sung by Marie Hare of Strathadam, New Brunswick, Canada on Ballads and Songs of the Miramichi Folk Legacy, recorded circa 1964.

Lw. "Waxford Girl" sung, played on banjo, and recorded by Nora Carpenter at her home in Salyersville, Maggoffin County, Kentucky 07-07-72

Lx. "Wexford Girl," sung by Mrs. Alvin Reed of Glenville, WV before 1970. Folk Songs of Central West Virginia I, by Michael E. Bush, 1971.

Ly. "Wexford Girl," sung by Rita Emerson of Glenville, WV; 1998, Davies recording.

Lz. "The Expert Girl" was contributed by Miss Lucile Morris, Springfield, Mo., Feb. 22, 1933. From: Randolph, Ozark Folksongs; 4 vols. 1946-50; reprinted Columbia, 1980, II, 92.

LAa. "Wexford Gal" sung by Long Tom, before 1901, Peshtigo, Wisconsin collected by Fayette Dublin, Jr. and published in Forest and Stream, Volume 56, p. 422 on June 1, 1901 in New York.

LAb. "Town of Waxford" [James W. Cline of Denville, New Jersey who used to work in Sullivan County lumber camps] published in New York Folklore Quarterly, V, p. 95-96; 11 stanzas. 1949.

Mostly American Traditional - "Oxford" Reduction

Ma. "Prentice Boy," my title. From a manuscript collection lent me in 1904 by Harry Fore of the University of Missouri. Compiled in Gentry County, apparently in the 1870s.

Mb. "Prentice Boy"- sung by Louie Hooper and Lucy White of Hambridge, Sept. 1903.[Cecil Sharp Manuscript Collection (at Clare College, Cambridge) (CJS2/9/41) with music.

Mc. "Oxford Girl." Sung by William A. Owens; Lamar County, Texas circa 1910. From Texas Folk Songs (1950), William Owens and Owens. The author, William A. Owens, was born on November 2, 1905-- he learned this song when just 5 years old.

Md. "The Oxford Girl." Written out in the summer of 1913 for Miss Jennie F. Chase of St. Louis by Addie McClard of French Mills, Madison County, whom Miss Chase heard sing it there. I have made the line and stanza divisions and have indicated what I take to be gaps. Belden B, Ballads and Songs, 1940.

Me. "Hang-ed I Shall Be." - Recorded by Mr. Brown, from the singing of Nellie S. Richardson, August, 1930 as remembered from the singing of Mr. James Simpson, born in 1830. From: Vermont Folksongs and Ballads; Flanders and Brown, 1933.

Mf. "The Oxford Girl." Sung by Mrs. Almeda Riddle as recorded by John Quincy Wolf in Miller, AR on 8/22/57. Learned from her husband's MS when she was 16 circa 1914. From The John Quincy Wolf Folklore Collection.

Mg. "The Oxford Girl." 1926 Written down from memory by Mrs. G. V. Easley, Tula, Mississippi, who describes it as one of the most popular 'ballets' in Calhoun county in her girlhood. From Ballads and Songs from Mississippi- Arthur Palmer Hudson The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 39, No. 152 (Apr. - Jun., 1926), pp. 93-194.

Mh. "The Oxford Girl." 1926 Communicated by Mr. T. A. Bickerstaff, a student in the University of Mississippi, who obtained it from his sister, Mrs. Audrey Hellums, of Tishomingo, Mississippi. From Ballads and Songs from Mississippi- Arthur Palmer Hudson The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 39, No. 152 (Apr. - Jun., 1926), pp. 93-194.

Mi. "Oxford Girl." Sung by Mrs. Sula Hudson, Crane, Mo., Sept. 15, 1941. From: Randolph, Ozark Folksongs; 4 vols. 1946-50.

Mj. "Oxford Town." Text written down in 1934 from the singing of Fred Harris, age 63, of Monticello, FL. From Morris, Folksongs of Florida, 1950; this is the B text.

Mk. "The Oxford Girl," sung by Mrs. Donna Everett of Huntsville, Ark. on August 11, 1958. Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 307, Item 5. Collected by Parler.

Ml. "The Oxford Girl." sung by James Turner of Elkins, Ark. on September 30, 1963. The Oxford Girl - James Turner of Elkins, Ark. on September 30, 1963. Ozark

Mm. "The Oxford Girl." [has Wexford ending]- sung by George Marshall, of Poteau (Okla.) on 6-25-1960 Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 386; Item 2. Collected by Ellen G. Ledbetter for Parler.

Mn. "Oxford Girl" sung by Linda Lee Jones of Huntsville, Ark. on January 10, 1960. Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 331, Item 4. Collected by Linda Lee Jones for Mary Celestia Parler.

Mo. "Oxford Town"- Sung by Mr. Earnest Hugley, Englewood, Colorado. from: Colorado Folksong Bulletin - Volume 3 - Page 46, 1964.

Mp. "A Murder Scoundrel (Oxford Girl)" - sung by W. A. Ammons, of Fairview, W. Virginia; communicated by Estelle T. Ammons, 1951. Has additional trial stanzas unique to tradition.

American Traditional- "Knoxville Girl" Variants

Na. "The Knoxville Girl," from Florence Mathis, from Franklin County, who learned it about 1906. Folk Songs of Middle Tennessee--George Bowell Collection notes by Wolfe.

Nb. "Knoxville Girl' from the manuscript of Mrs. Russell Wood, Kalkaska; she learned the song from her sister, Miss Lily Brown, who had memorized it about 1910 in Tawas City, Michigan.From: "Ballads and Songs of Southern Michigan" by Chickering and Gardner, 1939.

Nc. "The Knoxville Girl," sung by Sgt. Alexander Kirkheart, Recorded on March 29, 1938 at Fort Thomas, Kentucky, Campbell County; vocal with guitar- fast waltz tempo. Learned from his father back in mountains of West Virginia about 1916. AFC recording 1938004- 1698B recorded by Alan Lomax in 1938.

Nd. "Knoxville Girl," text from Selma Chubb (Turkey Creek, NC) c.1932 Scarborough A; A Song Catcher; 1938- ballads collected circa 1932

Ne. "Knoxville Girl," sent by Miss Bessie Musick, of Artrip, Buchanan County, VA. Scarborough B; A Song Catcher; 1938- ballads collected circa 1932.;

Nf. "Knoxville Girl," from Mary Rathburn MS about 1932, (Asheville NC) Scarborough C; A Song Catcher; 1938- ballads collected circa 1932.

Ng. "Knoxville Girl" No informant named. From: "Songs and Ballads Sung in Overton County, Tennessee: A Collection" by Lillian Crabtree, 1936, version A

Nh. "Knoxville Girl." No informant named. From: "Songs and Ballads Sung in Overton County, Tennessee: A Collection" by Lillian Crabtree, 1936, version B

Ni. "Knoxville Girl," sung by Katherine and Mary Magdalene Trusty of Paintsville, Johnson County KY on September 11, 1937

AFC recording 1937001- 1395A by Alan Lomax.

Nj. "The Knoxville Girl," sung by Howard Collins with dulcimer accompaniment on October 19, 1937 in Smithboro, KY; Knott County. AFC recording 1937001- 1541A recorded by Alan Lomax in 1937. From Kentucky Alan Lomax Recordings, 1937-1942.

Nk. "The Knoxville Girl (Part 1 and Part 2)." Sung by Mary Davis and Cora Davis on October 9, 1937in "Sibert, Manchester" KY; Clay County. AFC recording 1937001_1490A2 recorded by Alan Lomax in 1937. From Kentucky Alan Lomax Recordings, 1937-1942.

Nl. "The Knoxville Girl," sung by J.F. "Farmer" Collett of Marrowbone Creek; Gardner, KY (Leslie County). Recorded on September 26, 1937 (vocal and guitar- fast waltz tempo) at the home of John Sizemore by Alan Lomax. Library of Congress recording AFC 1937/001.

Nm. "Knoxville Girl," Elizabeth Minyard of Pine Mountain, KY; Harlan County on September 7, 1937. AFC recording 1937001- 1391B2 by Alan Lomax. From Kentucky Alan Lomax Recordings, 1937-1942.

Nn. "Knoxville Girl," sung by Fred Painter of Galena, MO Sept. 26, 1941. From: Randolph, Ozark Folksongs; 4 vols. 1946-50.

No. "Knoxville Girl - sung by Artus Moser of Wilson's Cove, NC, before 1949. Botkin, A Treasury of Southern Folklore; 1949. cf. Cox. Botkin calls it: A Southern version of the British broadside ballad, Berkshire Tragedy.

Np. "The Knoxville Girl," Sung by Marie Washam and J. R. Crymes of DeValls Bluff, Arkansas on June 13, 1954. Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 191 Item 5. Collected by Mary Jo Davis For M. C. Parler.

Nq. "The Knoxville Girl." Sung by anonymous female singer with guitar. Brown Collection of NC Folklore volumes 4, 1957.

Nr. "The Knoxville Girl." Sung by Mr. Al Bittick of Winkelman, Arizona September 3, 1958. Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 360, Item 4. Collected by Parler and O'Bryant

Ns. "The Knoxville Girl." Sung by Mrs. Maxine Hite of Prairie Grove, Arkansas on January 9, 1959. Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 264, Item 23. Collected by Mrs. Laura Willie for Mary C. Parler

Nt. "The Knoxville Girl." As sung by Mrs. George Ripley, Milford, Missouri on November 21, 1959. Max Hunter Folk Song Collection; Cat. #0430 (MFH #670). Minor editing. Unusual version.

Nu. "Knoxville Girl." Sung by Ralph E. Frazier, January 21, 1966. Collected by Sue Frazier. Burton and Manning I, 1967.

Nv. "Knoxville Girl." Sung by Mrs. Basil Casto; Jackson County, West Virginia c. 1969. Folk Songs of Central West Virginia I, by Michael Bush, 1971.

Nw. "Knoxville Girl," recording Vocalion A5121, 1926 sung by Lester McFarland and Robert A. Gardner; NYC.

Nx. "The Knoxville Girl," sung by Mrs. Jessie Monroe of Looneyville, West Virginia, 1953. From West Virginia Folklore - Volumes 4-9 - page 27, 1953.

Knoxville Girl (Early Commercial Recordings based on "Tanner" version)

Oa. "Knoxville Girl" sung by Arthur Tanner of Atlanta, Georgia (guitar and vocal), probably Earl Johnson on fiddle; Chicago Illinois, June, 1925. June 1925 (Silvertone 3515) Chicago, Illinois. Also “Knoxville Girl,” by Arthur Tanner & His Corn Shuckers (Columbia 15145-D, 1927) Atlanta, Georgia.

Ob. "The Story of the Knoxville Girl." Recorded by The Blue Sky Boys (Bluebird B7755).

Oc. "Mountain Girl" recorded by Hill Brothers of Kerrville, Texas on Savoy 3016 - side A; 1948. Listen on Honkingduck. This is a version of Knoxville Girl with a new ending.

Od. "The Knoxville Girl" Louvin Brothers on 1956 LP "Tragic Side of Life" also single release 1959.

Knoxville Girl (Collected Versions based on the Commercial Recordings)

Oe. "The Knoxville Girl." One of two texts contributed by Mrs. Minnie Church of Heaton, Avery county, in 1930. Brown Collection- G

Of. "The Knoxville Girl," sung by Frank Couch (Jim' Couch's son) recorded by Robert's in 1954, has different last stanza.

Og. "Notchville Girl." As sung by Betty Lou Copeland, Mountain View, Arkansas on May 26, 1969. From Max Hunter Folk Song Collection; Cat. #0767 (MFH #670). This is a cover of the Wilburn Brothers.

American Traditional- Expert/Export Girl Variants

Pa. "The Export Girl" - Sung by Louisiana Lou of Jackson, Mississippi, on 12-04-1933 Chicago Illinois. Bluebird recording B5424

Pb. "Expert Town." Sung by Mrs. Mildred Tuttle, Farmington, Ark., Dec. 31, 1941. Learned years ago from her parents. Randolph J

Pc. "Expert Girl." Sung by Mr. and Mrs. Arlie Freeman, Natural Dam, Ark., Dec. 14, 1941. Randolph K

Pd. "Export town" sung by Mrs. Matilda Amos of Marshall AR in April 1941, collected Garrison. From Mid-America Folklore - Volume 30, page 81, 2002.

Pe. "Export Girl." Sung by: Julie Powell. Recorded in Fox, AR, 7/18/53 Wolf E

Pf. "The Export Girl," sung by Jimmie Driftwood of Timbo, Ark. November 5, 1954.- Ozark Folk Song Collection- online; Reel 213, Item 5. Collected by Mary Celestia Parler

Pg. "Export Girl." Sung by: Mrs. Ben Daugherty. Recorded by John Quincy Wolf in Cave City, AR 8/10/58. Wolf B

Ph. "The Export Girl." Sung by Jewel Hawkins. Recorded in Batesville, AR 9/30/62 Wolf D

Pi. "Export Girl." Sung by: Mr. And Mrs. Berry Sutterfield. Recorded in Marshall, AR 8/1/63. Wolf F

Pj. "Export Girl." Sung by: Lowell Harness. Recorded in Pangburn, AR 7/29/63; Wolf G

Pk. "Export Town." As sung by Ollie Gilbert, Mountain View, Arkansas on August 8, 1969 Wolf

American Traditional--Flora Dean Variants

Qa. "Flora Dean." Sung by Mrs. Mary Wilson and Mrs. Townsley at Pineville, Bell Co., Ky May 1, 1917. . From: English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians Collected by Cecil J. Sharp and Olive Dame Campbell. Edited by Maud Karpeles; Volume I, 1932. Sharp A

Qb. "Flora Dean," sung by Aunt Molly Jackson, May 27, 1930 in New York City, recorded by Lomax.

English Traditional- Variants from Tristan da Cunha

Ra. "Maria Martini (Waxford Girl)," as sung by Frances Repetto. From Traditional Songs of Tristan da Cunha by Peter A. Munch; The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 74, No. 293 (Jul. - Sep., 1961), pp. 216-229. Also see: The Song Tradition of Tristan da Cunha; 1979. Version A.

Rb. "Maria Martini (Waxen Girl)," as sung by Lily Green about 1938 from The Song Tradition of Tristan da Cunha; 1979. Version B.

American Traditional- Waco Girl Variants

Sa. "Waco Girl." Esther Anderson Shinn, who taught it to me, says that she first heard it about 1906 from our aunt, Ethel Collins Anderson, a native of Catoosa in northeast Oklahoma. From: "The Waco Girl": Another Variant of a British Broadside Ballad by John Q. Anderson; Western Folklore, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Apr., 1960), pp. 107-118; Published by: Western States Folklore Society.

Sb. "Waco Girl," sung by Eddie Murphy of Crowley, Louisiana in June, 1934 as recorded by Alan Lomax. From, "Traditional Music in Coastal Louisiana: The 1934 Lomax Recordings" by Joshua Clegg Caffery.

Sc. "Waco Girl," sung by Fred Ross, Arvin, Calif., FSA Camp, on August 1, 1940. Learned from a migrant girl named Dorothy Ledford at Indio Camp in 1938. From Library of Congress recording of "Waco Girl, The, sung by Fred Ross, Arvin, Calif., coll. by Chas. L. Todd and Robert Sonkin, 1940. Voices from the Dust Bowl: The Charles L. Todd and Robert Sonkin Migrant Worker Collection, 1940 to 1941.

Sd. "Waco Girl," contributed by Ray C. Barlow, a native of Corpus Christi, Texas. His mother, whose parents came from Tennessee, taught it to him. [From: "The Waco Girl": Another Variant of a British Broadside Ballad by John Q. Anderson; Western Folklore, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Apr., 1960), pp. 107-118; Published by: Western States Folklore Society. Anderson B

American Variants "Noel Girl" Lexington Reduction

Ta. "Noel Girl," sung by Eva Shockley of Missouri in 1928; Randolph B. Mrs. Shockley insists that this piece is called "The Noel Girl," and has never doubted that it referred to the murder of Lula Noel.

"The Berkshire Tragedy," [hereafter "Berkshire"] a broadside ballad printed about 1700, tells the tale of a miller or miller's apprentice who brutally murders his sweetheart after she becomes pregnant with his child. The early prints of "Berkshire" were usually 44 stanzas long (sometimes printed with double lines as 22 stanzas). By the late 1700s and early 1800s a number of reductions were printed that were around 18 stanzas (or 9 double line stanzas) long. The reductions have been grouped into four main types which also entered tradition. There is evidence that earlier "archaic" reductions of the four types were printed that are now missing and only exist in rare traditional versions (see, for example, The Oxford Reductions). One possible antecedent titled "The Bloody Miller" may have been used to fashion the early Berkshire broadsides.

A, titled "The Bloody Miller" (as seen above), is a broadside from The Pepys Ballads, Volume 2, p. 156, which was printed by P. Brooksby in Pye Corner, London, in 1684[1]. A is subtitled, Being a true and just account of one Francis Cooper of Hocstow near Shrewsbury, who was a Millers Servant, and kept company with one Anne Nicols for the space of two years, who then proved to be with child by him, and being urged by her father to marry her he most wickedly and barbarously murdered her, as you shall hear by the sequel.

Rather than include A, a different ballad, as an appendix to B, "The Berkshire Tragedy" (the title ballad and originator of all the reductions and ballads that follow), I'm including A first-- since it's older and is the possible antecedent for B, although B has been completely rewritten.

A's tune "Alack for my Love I dye" is, according to Bruce Olson, a 17th century tune which is not known, but comes from a broadside ballad "William Grismond" (on which ours here seems to be modeled), ZN1988, which has appeared in Scots tradition as "William Guiseman/Graham", and from that there are traditional tunes (Grieg-Duncan #190)[2]. The broadside's title includes the date of Grismond's murder: The downfall of William Grismond: or, A lamentable murder by him committed at Lainterdine in the county of Hereford, the 22 of March, 1650, with his woful lamentation.

Since "William Grismond" also killed his pregnant lover rather than marry her and since the chorus is nearly identical, this broadside dated 1658-1664, was likely modeled by the unknown author of "The Bloody Miller." Olsen also mentioned that "Hyder E. Rollins, In The Pepys Ballads III, reprinted the [Bloody Miller] ballad, and quoted a diary entry of Feb. 20, 1684, stating that the murder had been committed on the 10th, the Sabbath[3]." The actual date of the murder would be Sunday February 10, 1684-- ten days earlier. The entry was made by Phillip Henry whose dairy is found online (Google Books) titled, Diaries and Letters of Philip Henry, M.A. Of Broad Oak, Flintshire, A.D 1631-1696; by Philip Henry, M.A. At the top of p. 323 is found the full diary entry:

“I heard of a murther in Salop on Sabb. Day ye 10. instant, a woman fathering a conception on a Milner was Kild by him in a feild, her Body laye there many dayes by reason of ye Coroner's absence.”

Philip Henry was a minister who lived about 20 miles from the Shropshire town of Shrewsbury which was also called Salop[4]. Further evidence that the ballad was "a true and just" account of a murder on Sunday February 10, 1684 near Salob was obtained in 2005 by a local historian Peter Francis and independently by writer Paul Slade, who was investigating the source of "The Knoxville Girl."

The evidence was first reported by Pete Francis[5] who wrote, "At the time (1684) the nearby village of Minsterley didn't have its own church and marriages, burials etc. took place at Westbury (3 or 4 miles to the west). The records there contain the following entry[6]:

1st March 1683 [our year 1684] Anne Nicholas murdered (truculenter occisa) - burial

As far as I can tell, the Latin phrase means something like 'savage death'. There are a number of baptism entries which could refer to Anne and her murderer (Francis Cooper), the most likely of which would mean he was 27 and she 23 at the time. Most interesting of all, however, is the following entry:

24th March 1683 [our year 1684] Ichabod son of Francis Cooper, homicide, and Anne - baptism

In his series of online articles about murder ballads also found his book[7], journalist Paul Slade has written about the origins of Knoxville Girl and traced that version back to The Bloody Miller. He claims he received the same information on June 30, 2005 from Shropshire Archivist Jean Evans-- which was several months before Francis posted it[8].

With the diary entry of Feb. 20, 1684 and burial record of Anne Nicolas and birth record of Ichabod, son the murderer Francis Cooper--it's clear that "The Bloody Miller" was "a true and just" account of a murder on Sunday February 10, 1684 near Salob. The Bloody Miller was written shortly thereafter-- based on the form and melody of "William Grismond[9]." It was printed by P. Brooksby in Pye Corner, London (see copy above).

The ballad featured a chorus; "I for my transgression must dye," that appeared similarly at the end of each stanzas and was patterned after "Alack for my Love I must dye." In "William Grismond" the chorus is similarly: "And it's for my offence I must die." Cf. "The Pining Maid," Roxburghe Collection III, 118.

The Bloody Miller is only 14 stanzas and I've included just 7 below to help tell the ballad story:

I was a Miller by my Trade,

it plainly doth appear,

Pretending love unto a Maid,

whose Father lived near,

But she for my acquaintance,

poor soule, did pay full dear:

I for my transgression must dye.

[A miller seduces a maid pretending to love her]

Tho' I was young and likely too,

I wanton was and wild,

And by my amorous carriage she

most strangely was beguil'd,

She did beleive my flattering tongue

till I got her with Child:

I to my transgression must dye.

[He flatters her, and she believes him until she becomes pregnant.]

Her Father sent her to the Mill

to ask him her to marry;

Which he then seemed to refuse,

and told her she must tarry

but by my strange & treacherous tricks

I strangely did miscarry:

I for my transgression must dye.

[Her father sends her to the mill to offer marriage, but he refuses.]

She told me I must marry her,

or for the Child provide;

Five pound I offer'd, which by her

was utterly deny'd;

She in the full conclusion

by me was mortified:

I for my transgression must dye

[She offered him marriage or for him to provide for her child. He offered five pounds which she denied.]

One Sunday on an Evening tide

for her poor soule I sent

Who came to me immediately

not dreaming what I meant,

And so into a secret place

we sinful sinners went:

I for my transgression must dye.

[On Sunday he sent for her and led her to a secret place where he kisses her-- then murders her.]

The Murder Scene- The Bloody Miller

My bloody fact I still denied,

disown'd it till the last,

But when I saw for this my fact

just judgment on me past,

The blood in Court ran from my nose

yea; ran exceeding fast;

And for my transgression must dye.

[He denies killing her, then he is taken to court, his nose bleeds and he is convicted of his crime.]

So like a wretch my daies I end,

upon the Gallow-Tree,

And I do hope my punishment

will such a warning be,

That none may ever after this

commit such villany;

And for my transgression I die.

[He's sentenced to death upon the gallows and warns others not to commit crimes of such villany.]

Berkshire broadside-- Bodleian, ESTC: T204012; Antiq c. E9 (125), dated c.1700

Ba, the fundamental broadside and title of this study is illustrated above and dated c. 1700 by Ebsworth[10]. One early broadside print is titled "The Berkshire Trgedy; Or, the Wittam Miller: with an Account of His Murdering His Sweetheart." B, the progenitor of the subsequent ballads in this series, also appears with the correct spelling of "Tragedy" as in Bc: "The Berkshire Tragedy; Or, the Wittam Miller With an Account of his Murdering his Sweetheart." There are a number of different title variations of the same broadside. In this study, versions of B will appear as "The Berkshire Tragedy" or sometimes shortened to just "Berkshire." The relationship between A and B is tenuous at best since A is a different ballad than B. In this study A is included only as a possible ballad from which B was modeled-- since A is a different ballad and not related to B and its reductions. Some of the similarities however are obvious:

1. The ballad story is told in the first person as a "dying confession" from a repentant murderer.

2. A miller or a miller's apprentice seduces a girl and she becomes pregnant.

3. When his lover or one of her parents tries to persuade him to marry her, he lures her to a secluded place and murders her.

4. When accused, the murderer's blood runs from his nose, or in subsequent versions, he claims the blood on his hands and clothes is from a nosebleed.

5. He eventually confesses his crime or it is found out and he is hung.

Even though the theme of B and some details may have been based on A -- there are enough significant differences to prevent B and its reductions to be closely related to A: The 6 line form of A with a chorus has been replaced with a standard quatrain in B. Although it may be shown that A can easily be written in quatrain form[11], there is no chorus in B, a difference that cannot be reconciled. The text of A although similar in plot is very different and except for two or three lines cannot be part of B and its reductions. The fourteen stanzas of A have been expanded into twenty-two[12] in B. After murdering his sweetheart with a stick, as in most versions of B, he throws her body into a river (see also: Banks of the Ohio). The location of A has been moved from Shropshire town of Shrewsbury to Wittam (usually "Wytham" or in Roxburghe-- "Wittenham") near Oxford in B and B therefore is about a similar murder with different people[13]. The ballad story of B could have been modeled after A --just as A was likely modeled after "William Grismond." B, however, includes as its reductions the print versions of "The Wexford Tragedy," "The Cruel Miller," and the "Lexington Miller," as well as the primary traditional reductions of "Oxfordshire Lass," "Lexington Murder," "Wexford Girl" and "Butcher Boy."

It should again be noted that the title of this study is "The Berkshire Tragedy," indicating that the possible role of A is hypothetical. Two Berkshire reductions have the same title as A: the first "Bloody Miller" is an alternate broadside title of the "Cruel Miller" text while the second is an old traditional version from North Carolina titled two ways- "The Bloody Miller" and also "The Bloody Miller, or, The Murdering Miller." Neither of these Berkshire reduction titles show a close resemblance to A, a different ballad.

Here is a short composite I've arranged that shows that B and A are at least compatible and that some lines in A are similar to those in B:

Bloody Miller /Berkshire Tragedy (composite)

“By chance upon an Oxford lass, [Berkshire]

I wanton was and wild, [Bloody Miller]

She told me I must marry her, [Berkshire]

If she with me would lie. [Berkshire]

And by my amorous carriage, [Bloody Miller]

She most strangely was beguil'd,

She did believe my flattering tongue

Till I got her with child.

She told me I must marry her, [Bloody Miller]

Or for the child provide;

Five pounds I offer'd,

Which by her was utterly deny'd.

One Sunday on an evening tide [Bloody Miller]

For her poor soul I sent

Who came to me immediately

Not dreaming what I meant.

There kissing and embracing her, [Bloody Miller]

My treachery appear'd,

I like a cruel bloody wretch,

Whom she so little fear'd,

Thus I deluded her again, [Berkshire]

And so into a secret place [Bloody Miller]

Then took a stick out of the hedge, [Berkshire]

And struck her in the face. [Berkshire]

But she fell on bended knee, [Berkshire]

For mercy she did cry,

"For heaven's sake don't murder me,

I am not fit to die."

“From ear to ear I slit her mouth, [Bloody Miller]

And stabbed her in the head,

Till she poor soul did breathless lie,

Before her butcher bled.

“And then I took her by the hair, [Berkshire]

To cover the foul sin

And dragged her to the river side,

And threw her body in.

So like a wretch my days I end, [Bloody Miller]

Upon the gallows tree,

And I do hope my punishment

Will such a warning be,

That none may ever after this

Commit such villany.

Ironically, the composite ending from the Bloody Miller resembles the two-stanza warning that is found at the end of the standard Wexford Girl traditional ballad. The two stanzas above with a line of the Bloody Miller inserted don't suffer badly for it. Although this is a drastic reduction, the traditional and print versions derived from Berkshire were all reductions-- some of a similar length.

Ebsworth says about the Berkshire broadside[14], "This is a Berkshire variation of the tale (already reprinted, disjointedly, on pp. 68, 175) entitled, 'The Oxfordshire Tragedy; or, The Virgin's Advice.' Therein the seducer who murders his victim is an Oxford Student of theology, but here he is a Miller of Wittam, probably Wittenham. Both ballads were sung to the same tune, and of date near 1700." Despite the similar theme of "The Oxfordshire Tragedy; or, The Virgin's Advice," also known as "Rosanna's Overthrow," it is significantly different and does not met the criteria for inclusion with these murder ballads: 1) it is not a murderer's confession; 2) it is not about a miller; 3) there is no reference to a nose-bleed; and 4) there are unique supernatural elements in the Oxfordshire Tragedy's ending.

"The Berkshire Tragedy; Or, the Wittam Miller," as written in 22 stanzas, begins[15]:

Young Men and Maidens, all give ear, to what I shall relate;

O mark you well, and you shall hear, of my unhappy fate:

Fear unto famous Oxford town, I first did draw my breath —

Oh! that I had been cast away, in an untimely death[16].

My tender parents brought me up, provided for me well,

And in the town of Wittenham[17] they placed me in a Mill.

By chance upon an Oxford Lass I cast a wanton eye,

And promis'd I would marry her, if she would with me lie.

But to the world I do declare, with sorrow, grief, and woe,

This folly brought us in a snare, and wrought our overthrow;

For the Damsel came to me, and said — "By you I am with child:

I hope, dear John, you 'll marry me, for you have me defil'd."

B at 22 stanzas or with subdivided lines (the Berkshire broadsides are written as 44 stanzas) is obviously more detailed than A at 14 stanzas. The date of the murder is similar-- in B it's a month after Christmas and in A, February 10. An important element is added in B-- the stick as murder weapon as found in stanza 6 [see stick in c. 1700 wood-cut above]:

I told her, if she 'd walk with me aside a little way

We both together would agree about our Wedding-day.

Thus I deluded her again into a private place,

Then took a stick out of the hedge, and struck her in the face.

The knife as the murder weapon is found in the Scottish reduction of B, but that may be coincidental. The first two lines (or four lines) are similarly found in the first stanza of the US murder ballad, "Banks of the Ohio." Other textual similarities in B and its reductions are found in "Girl I Left Behind Me," "Boston Burglar" and a later reduction--"Knoxville Girl[18]." The nose-bleed which helped convict Francis Cooper in the "Bloody Miller" now is used as an alibi for the blood on his hands:

"Oh! what's the matter?" then said he, "you look as pale as death,

What makes you shake and tremble so, as tho' you 'd lost your breath,

How came you by that blood upon your trembling hands and cloaths?"

I presently to him reply'd, "By bleeding at the nose!"

In British ballads the nosebleed is known as an omen of badluck[19] and is one of the most important identifiers in this murdered-sweetheart ballad. B begins “Young men and maidens all give ear” and was printed in London including printers Dicey, Sympson; Howard & Evans; Pitts; and Catnach and the provinces including Coventry; Birmingham; Banbury, while others including the c. 1700's version in the Bodleian, are without imprint[20].

Exceptional are the two Edinburgh printings of B. The first, Bb, was made by Robert Drummond for John Keed in an eight page chapbook dated 1744 and titled, “The BERKSHIRE TRAGEDY, OR, The WHITTAM Miller, Who most barbarously murder’d his Sweet-heart: With his whole Trial, Examination and Confession; and his last dying Words at the Place of Execution.” It concludes, “The last dying words and confession of John Mauge, a Miller, who was executed at Reading in Berkshire, on Saturday the 20th of last month, for the barbarous murder of Anne Knite, his sweet-heart.”

Drummond's print gives the name of the murderer-- John Mauge, the name of the murdered-sweetheart-- Anne Knite, and the date. Since Saturday the 20th happened in the month of June in 1744, the printing would have been made in July, 1744. It should be noted that the date in the ballad text and this date do not correspond. Despite this detailed information, no record of this murder has yet been found. Drummond's broadside information was published in "Notices of Fugitive Tracts" by James Orchard Halliwell, 1851 on p. 90:

118. THE BERKSHIRE TRAGEDY, OR THE WHITTAM MILLER, who MOST BARBAROUSLY MURDER'D His SWEETHEART. 12mo, Edinburgh. Printed for John Keed, in the Swan-closs, 1744.

In verse, with a cut of the miller on the gallows. It concludes with "the last dying words and confession of John Mauge, a miller, who was executed at Reading, in Berkshire, on Saturday, the 20th of last month, for the barbarous murder of Anne Knite, his sweetheart."

Halliwell's "Notices of Fugitive Tracts" was used by Cox (Folk Songs of the South, 1925, p. 311) and others in their song notes describing the shortened US variants.

The second exceptional version from Edinburgh is Be, "The tragical ballad of the miller of Whittingham Mill. Or, a warning to all young men and maidens[21]."It was printed in a chapbook in Edinburgh in 1793 and also in Glasgow in 1800[22].

Front page of the Edinburgh chapbook, the version is dated 1793

"The Miller of Whittingham Mill" has 47 stanzas, three more than most standard long broadsides and is the longest extant broadside of Berkshire. It is missing Berkshire's stanza 2, and has a different last line of 8. Additionally, it adds 4 stanzas near the end:

42 The ruin of innocence let ne’er,

like mine your study be;

But when that Satan tempts you fore,

from his suggestions flie.

43 Likewise young women all take care,

how you your charms do yield,

By doing so too soon you lose,

your virtue and your shield.

44 When men do tempt you to this guilt,

remember with a sigh,

That horrid and most barbarous crime,

for which I now must die.

46 Me pardon for the bloody deed,

for which I’m doom’d to death,

And let my tears flow fast therefore,

e’er I resign my breath.

for which there are no corresponding stanzas. Another possible location for the mill and murder has been added-- Whittingham which is similar to the text "Wittam then" found in Berkshire and the name given by Ebsworth-- "Wittenham." The additional stanzas have not been found in tradition.

Bf, a Catnach print from the early 1800's is titled, Discovery of an Extraordinary MURDER Committed by a Respectable Miller, of Wittam in Berkshire. The print which features several woodcuts (one depicting the miller holding the unconscious girl by the hair and beating her with a large stick resembling a club) and a lengthy subtitle which begins, "Upon the body of his sweetheart, in December last, he first seduced her, and got her with child, . . ." As with the 1744 Scottish print by Drummond a date is affixed (December last) which purports to be the actual date of the heinous crime. Apparently this was done to promote sales since a real murder is more scandalous-- thus more appealing to prospective buyers.

Despite the obvious popularity of the various print versions of "The Berkshire Tragedy," forty-four or forty-seven stanzas were too wieldy to be memorized by a balladeer so shorter versions evolved from print and tradition that could more easily be sung[23]. A number of different reductions were created that stemmed from the long Berkshire broadside. The reductions are labeled: 1) The Wexford Reductions; 2) The Lexington Reductions; 3) The Butcher Boy Reductions and 4) The Berkshire/Oxford Reductions. These are the four primary reductions that were made and from these come the secondary reductions.

THE ORIGINAL OXFORD REDUCTIONS

The original reduction was based solely on the original 44-stanza Berkshire Tragedy broadside. The first reduction was named for "Oxford Town" and "Oxford lass" as found in the opening stanzas. This English reduction is made up mostly from text of the long Berkshire broadside. No print version of this reduction has been found and there have been no traditional English versions known to have been based on it although traces of text have been found in English tradition. The original or archaic Oxford Reduction is known through two traditional versions collected in the United States. The first and most archaic was collected in 1930 from Maryanna Harmon in Tennessee[24] and may be viewed later in this study. It is a reduction of 18 stanzas and I estimate it was learned in England by the 1760s. The second, titled "Oxfordshire Lass" was learned by Jason Ritchie of Knott County, Kentucky who claimed he learned it from a local family. The Ritchie version is more modern and has some minor corruption from other local versions. This text will be given in full after the list of identifiers.

In most of the reductions the first stanza (introduction) and the last 20 stanzas (incarceration, trial) are eliminated. Stanzas 4-7 and 14 are rarely found in tradition or have been changed and include the marriage agreement, pregnancy and mother's request for marriage. After these eliminations there are 18 stanzas which are the fundamental stanzas found in the reductions. Here are the main identifiers of the Berkshire or Oxford Reduction:

tender parents

Oxford town/Oxford lass

with a wanton eye

If she with me would lie

folly/snare, overthrow

deluded her again

creature think

Christmas last

devil persuade

heaven's sake

cover sin

blood of innocence

snatched the candle (sim. grabbed or took the candle)

to the mill

was amazed/on me gazed

my man (miller)

rest/ breast

Floating-- brother's door

Hillsferry town/Hindley Ferry town

[Ending:] Have mercy upon me I pray/and so receive my soul.

The ending is found only in Maryanna Harmon's reduction, and Jason Ritchie's reduction (see immediately below). Harmon's variant has a stanza not found in any of the reductions: the payment of a reward of (two) guineas published by the murderer in the Post Boy newspaper to anyone who should find the missing damsel. This newspaper under the Post Boy title was in circulation from 1695-1728 and is important in dating the original broadside. Under printer George James, it became a daily paper, The Daily Post Boy, in October of 1728, and it ran daily until 1736. The prints of the broadside that mention "Post Boy" should logically be dated 1695-1728 or possibly as late as 1736.

The Oxfordshire Lass- from Jason Ritchie (1860- 1959) of Knott County, Kentucky as learned from the Williams family.

1. My parents raised me tenderly

And provided for me well,

It was in the town of Oxfordshire,

They placed me in a mill.

2. It was there I met an Oxford lass

with a dark and charming eye,

I asked her if she would consent

one night with me to lie.

3. Then what to do I did not know

I considered night and day;

The devil he persuaded me

To take her life away.

4. I went unto her sister's house,

At eight o'clock at night,

Poor creature little did she think

I owed her any spite.

5. I asked her if she would walk with me,

in the field a little way.

That we could talk and soon agree,

and appoint the wedding day

6. All hand in hand we went along,

unto a lonesome place;

I drew a stake out of the hedge

And smote her over the face.

7. Down on her bended knees she fell

and did for mercy cry,

For heavens sake don't murder me

for I am not fit to die

8. No mercy on her I did show

but wounded her full sore,

O there I put my love to death

whom I cannot restore.

9. Then for to wash the stain away

I took her by the hair

And dragged her to the river

and I threw her body there.

10. Then straightway to the mill I run

like one all in a maze.

The miller fixed his eyes on me

and at me he did gaze.

11. Saying "What's this blood upon your hands,

likewise upon your clothes?"

I answered him immediately,

"The blood is from my nose."

12. Next day this maiden she was missed

and nowhere could be found,

And I was apprehended soon,

to the high sheriff bound.

13. Her sister there against me swore,

she said she had no doubt,

She swore she thought I murdered her,

by me calling of her out.

14. O Lord, give me a praying heart

and time for to repent,

I soon will leave this wicked world,

so shamefully I am sent.

15. Lord wash, my sins and guilt away,

they are of the darkest fold;

O lord from heaven look down on me,

and Christ receive my soul.

The two stanza ending corresponds to Berkshire's stanzas 42 and 44. Over time, the Oxford Reduction changed--this ending disappeared and the marriage agreement (in Ritchie's version: "I asked her if she would consent/one night with me to lie") and pregnancy were removed. The stanzas about the devil are no longer found and running to the mill. Only the Lexington Reduction retained some of the archaic text from the original or archaic Oxford Reduction. The modern or standard Oxford versions more closely resemble the standard Wexford Reductions without the two-stanza ending.

Traditional versions with any of the above Berkshire/archaic Oxford identifiers added, are usually older and representative of an early reduction. The identifiers are not found in, for example, the standard Wexford traditional reduction-- which has few of the Berkshire identifiers in its standard text. Since the Berkshire/Oxford Reduction would be used by professional broadside writers to recreate a print version-- naturally many these identifiers will be present. It may be the case that the first Cruel Miller broadsides were penned by a professional writer working for a printer and possibly a writer was used by Deming in The Lexington Miller, but the chapbook printer in this next reduction certainly borrowed the following reduction from tradition.

The following print, my Ca, was recently found (2016) in a chapbook and represents an older reduction of the Wexford tradition:

Chapbook cover of Wexford Tragedy -1818

Ca, "The Wexford Tragedy Or, The False Lover" was printed in a Scottish chapbook in 1818 by [Yellich and] T. Johnston of Falkirk, Scotland. It is a reduction of 8 1/2 stanzas or divided 17 stanzas and appears: "The freemason's song; to which are added, The Wexford Tragedy Or, The False Lover and My Friend and Pitcher. Printed for Freemason[s], 1818." I give the text in full with divided stanzas and punctuation changes as found in printed versions of B:

THE FALSE LOVER. [Wexford Tragedy]

1. My parents rear'd me tenderly,

Endeavouring for me still,

And in the town of Wagan

They brought me to a mill.

2. Where there I spied a Wexford girl,

That had a black rolling eye,

And I offered to marry her

If she would with me lie.

3. In six months after this,

This maid grew big with child,

Marry me, dear Johnny,

As you did me beguile.

4. I promised to marry her,

As she was big with child:

But little did this fair maid know

Her life I would beguile.

5. I took her from her sister's door,

At 8 o'clock at night,

But little did this fair maid know,

I her bore a spite.

6. I invited her to take a walk

To the fields a little way,

That we might conclude a while

And appoint a wedding day.

7. But as we were discoursing

Satan did me surround

I pulled a stick out of the hedge,

And knock'd this fair maid down.

8. Down on bended knees she fell,

And for mercy she did cry;

I'm innocent, don't murder me,

For I'm not prepar'd to die.

9. He took her by the yellow hair

And dragged her along,

And threw her in the river,

That ran both deep and strong.

10. All in the blood of innocence

His hands and clothes were dy'd

He was stained with the purple gore

Of his intended bride.

11. Then returning to his mother's door,

At 12 o'clock at night

But little did his mother think

How he had spent the night.

12. Come tell me dear Johnny

What dy'd your hands and clothes?

The answer he made her was,

Bleeding at the nose.

13. He called for a candle

To light himself to bed,

And all the whole night over,

The damsel lay dead.

14. And all the whole night over,

Peace nor rest he could find,

For the burning flames of torment,

Before his breast did shine.

15 In three days after,

This fair maid she was miss'd,

He was taken up on suspicion,

And into jail was cast.

16. Her sister swore away his life,

Without either fear or doubt,

Her sister swore away his life,

Because he call'd her out.

17. In six weeks after that,

This fair maid was found,

Coming floating to her brother's door

That liv'd in Wexford town.

This establishes a variant of the Wexford reduction which was missing until now. Notice the course rhymes, awkward verbs ("That we might conclude a while"- stanza 6), missing ending and the shift from 1st person in stanza 9-- which indicates that this was created not by a professional print writer but was more likely the capturing of tradition. I had already postulated the existence of this and other printed reductions before finding it in November, 2016 at Google Books. This has "The Girl/Maid I Left Behind Me" opening line as found in a number of versions including the New Brunswick Miramichi's "Wexford Lass," where the whole first stanza is borrowed. As an important printed variant of the Wexford tradition, it represents a capturing of tradition in 1818. Older reductions may still exist, since I estimate the first reductions were made in the 1700s. By its traditional nature, "The Wexford Tragedy" would have evolved from an earlier unknown Irish or possibly an English print. Even though printed in Scotland, this Wexford reduction is not from with the Scottish tradition but is rather--associated with that tradition. Steve Gardham of Hull, Yorkshire, an expert of broadsides and prints, comments: "Wexford is in Ireland and though it is clearly derived from Oxford the most likely progression is that the alteration to Wexford took place in Ireland. Having had a cursory look at the version I would say it's pretty certain it was taken from oral tradition."

One older traditional version that resembles "The Wexford Tragedy" is Cb, "The Worcester Tragedy," collected by Kenneth Peacock in 1959 from Mrs Charlotte Decker of Parson's Pond, Newfoundland. The chapbook and this similar traditional version establish an earlier tradition of Wexford that I've called "archaic" -- indicating that these are older and from a different reduction than the standard versions. See more on the Wexford Reductions later in the study.

By the 1820s a number of 18-stanza broadside reductions where printed in England under the titles "The Cruel Miller," "The Cruel Miller, or, Love and Murder," "False-Hearted Miller," and "Bloody Miller" (not A, also titled "Bloody Miller"). Although the titles are different, these broadsides, my D versions, are the same length with only minor differences in text. Since they mention "Wexford Town," the four broadsides are associated with and may be grouped with the "Wexford" reductions.

"The Cruel Miller," Dc, will refer to the four reduced 18 stanza (also written as 9 double-line stanzas) broadside versions. Of the four titles, "The Cruel Miller, or, Love and Murder," dated c. 1813, and "Bloody Miller," (Imprint: Thompson, Printer, no. 156, Dale-Street, Liverpool) dated between 1789-1820, are among the earliest printed. It's reasonable to assume all four titles were printed by c. 1820 and other duplicate prints followed that were made until the late 1800s. This reduction was issued by many printers, both in London with imprints by Disley; Such; Fortey; Pitts; Catnach and outside London with imprints by Birmingham; Worcester; Newcastle; Liverpool; North Shields; Manchester), plus several issues with no imprint[25].

This Catnach broadside, Da, is thought by David Atkinson to be one of the earliest versions of the Cruel Miller group. The text follows:

The Cruel Miller;

Or, Love and Murder.

Printed by J. Catnatch, 2 & 3, Monmouth-Court

My parents educated [me], good learning gave to me,

They bound me to a miller to which I did agree,

Till I fell a courting a pretty maid, with a black and a rolling eye,

I told her I would marry her if she would with me lie.

I courted her for six long months a little now and then,

I thought it was a shame to marry her, I being so young a man,

At length this fair maid proved with child and aloud on me did cry,

Saying Johnny dear, come marry me, or else for you I'll die.

I went unto her sister's house at ten o' clock at night,

And little did this fair maid think, I owed her such a spite,

I ask'd her to take a walk all in those meadows gay,

And there to sit and talk awhile, and fix our wedding day.

I took a stick out of the hedge and struck her to the ground,

And soon the blood of innocence, came trick'ling from the wound,

She fell upon her bended knees, and did aloud for mercy cry,

Saying John dear don't murder me, for I am not fit to die.

I took her by her curly locks and dragg'd her through the glen,

Until I came to a river's side, and then I threw her in,

Now with blood from the innocence, my hands & clothes were dy'd,

Instead of being a breathless corpse, she might have been my bride.

Arriving at my master's house at twelve o'clock that night,

My master rose and let me in by striking of a light,

He asked and questioned me, what stained my hands and clothes!

I made him an answer as I thought fit, by the bleeding of my nose.

I asked for a candle to light myself to bed,

And all that long night my true love she laid dead,

And all that long night no comfort could I find,

For the burning flames of torments before my eyes did shine.

All in a few hours after, my true love she was miss'd,

They took me on suspicion and I to jail was sent,

Her sister prosecuted was, for reason and for doubt,

Because that very evening we were a walking out.

All in a few days after, my true love she was found,

A floating by her brother's house, who lives in ---- town,

Where the judges and juries did so both agree,

For murdering my own true love, then hanged I must be.

"The Cruel Miller, or, Love and Murder" is identified by the blank in front of town ( ----- town) found at the end of the second line in the last stanza. This was left blank in order for the singer to fill the blank with the name of his or her local town. In the other Cruel Miller broadsides it's always "Wexford Town" which has been changed from Berkshire's "Oxford Town." The "Wexford" found in the broadside has been taken from a reduction like the printed "Wexford Tragedy," which naturally has "Wexford" in the text. The Cruel Miller broadsides are the first known English reductions of Berkshire (see the Oxford Reductions) with other changes-- some from the Wexford Reductions (for example, "with a black(dark) and rolling eye[s]"). The Standard Wexford Reduction, a more recent reduction, is also found traditionally in America -- mainly in Canada/New England and Irish-American versions-- but rarely in the UK. The Wexford Reductions are assumed to originate in Ireland and are associated through a common stanza with the Scottish Butcher Boy Reductions.

The influence of the shortened broadside, The Cruel Miller, is found mainly in traditional versions in England collected in the early 1900s. In the past, it's influence has been exaggerated. For example in America, Cox's heading for the ballad in his 1925 book, "Folk Songs of the South" is "Wexford Girl (Cruel Miller)."

In 1957 Malcolm Laws suggested that evidence of The Cruel Miller was not found in American tradition and that the "Wexford Reduction" was a "deliberate recomposition[26]" rather than just a variant made by traditional singers. This is proven by the recently discovered print version Ca, The Wexford Tragedy, from a Scottish chapbook (see above). Laws was implying therefore that the Wexford "recomposition" was printed and unknown. This would indicate other unknown Wexford prints exist since the quality of reduction C suggests it was sung orally and written down by printer Thomas Johnston or one of his associates as a filler ballad for the Freemason's chapbook in 1818.

Evidence that the Cruel Miller wasn't just copied from Berkshire is the significant change of "Oxford Town" to "Wexford Town[27]" and the change from "Wanton eye" to the common "black (dark) and rolling eye." It's logical to assume then that these and some of the changes came from The Wexford tradition-- considered to have originated in Ireland. The discovery of the reduction in a Scottish chapbook, however, doesn't necessarily change the source of the Wexford chapbook text. It's still taken from the Wexford tradition (Ireland) and is another reason the traditional Scottish versions are considered to be linked with the Wexford tradition.

In North America, Wexford versions are found primarily in New England and Canada but are also scattered throughout the United States where they have been disseminated in the mid-west and west under a variety of titles. Since many of these versions came originally to America from emigrants of Irish decent it's reasonable to assume that Laws was correct and that it was once printed in Ireland from a tradition that is now lost. Versions of The Wexford Girl and related titles are old and certainly pre-date the Cruel Miller which would not have enter tradition until the late 1820s in England. All the reductions were achieved in part by dropping the beginning stanza, reducing, changing or eliminating the marriage agreement/pregnancy stanzas (4-7), eliminating the mother's marriage request stanza (14) and all of the "judicial" stanzas (last 20 stanzas) from 44 stanza "The Berkshire Tragedy." Since the short Cruel Miller broadside isn't long, here's the complete text of the Pitts' version, dated c. 1820 which is written in double lines (9 instead of 18 stanzas):

The Cruel Miller

My parents educated me, good learning gave to me,

They bound me apprentice to a miller with whom I did agree,

Till I fell courting a pretty lass with a black and a rolling eye,

I promised for to marry her if she with me would lie.

I courted her for six long months a little now and then,

I was ashamed to marry her being so young a man,

Till at length she proved with child by me and thus to me did say,

Ah Johnny do but marry me or else for love I die.

I went unto her sister's house at 8 o' clock at night,

And little did this fair one know I owed her any spite,

I asked her if she would take a walk thro' the meadows gay,

And there we'd sit and talk awhile upon our wedding day.

I took a stick out of the hedge and hit her on the crown,

The blood from this young innocent came trickling on the ground,

She on her bended knees did fall and aloud for mercy cried,

Saying Johnny dear don't murder me for I am big with child.

I took her by her yellow locks and dragged her to the ground,

And we came to the river's side where I threw her body down,

With blood from this young innocent my hands and feet were dyed,

And if you'd seen her in her bloom she might have been my bride.

I went unto my master's house at 10 o' clock at night,

My master getting out of bed and striking of a light,

He asked me and questioned me what dyed my hands and clothes.

I made a fit answer I'd been bleeding at the nose.

I then took up a candle to light myself to bed,

And all that blessed long night my own true love lay dead,

And all that blessed long night no rest at all could find,

For the burning flames of torment all round my eyes did shine.

In two or three days after this fair maid she was miss'd,

I was taken on suspicion and into prison cast,

Her sister prosecuted me for my own awful doubt,

Her sister prosecuted me for taking of her out.

In two or three days after this fair maid she was found,

Came floating by her mother's door near to Wexford town,

The judge and the jury they quickly did agree,

For the murder of my true love that hanged I must be.

Woodcut c. 1820 by Catnach depicting the brutal murder

D, The Cruel Miller, is based on Berkshire (Oxford Reduction) with some changes from the Wexford Reduction as found in the "Wexford Tragedy" and text from other sources. The Cruel Miller represents, as a secondary reduction print, an unknown English tradition from whence the Pollyanna Harmon's and Jason Ritchie's Berkshire reductions came. "The Butcher Boy" and "The Lexington Murder" are the other two other reductions. Additional titles and variants like "Knoxville Girl," "Ekefield/Ickfield Town," "The Prentice Boy" and "Waco Girl (US southwest) are derived from these older somewhat distinct reductions. If you compare The Cruel Miller with the original Berkshire broadsides (c.1700) and then the Wexford Tragedy chapbook print you can see, for example, that some of the changes found in the Cruel Miller were taken from the Wexford tradition, others are a reworking of Berkshire and others (too young to marry) come from "other" sources.

The Cruel Miller has influenced many of the circa 1900 English traditional ballads but remnants of text (such as 'tender' parents) from the older reductions remain. In his short article, "Memory, Print and Performance (‘The Cruel Miller' Revisited)[28], Tom Pettitt compares the long broadside (B, The Berkshire Tragedy) with the short broadside (D, The Cruel Miller) and a Scottish and English traditional ballad. In this way it's much easier to see the differences between the older broadsides and the reductions. In another article "Worn by the Friction of Time[29]" Pettitt has also pointed out that traditional versions have borrowed textual phrases and lines from of the Berkshire broadside that are not part of the Cruel Miller broadsides. These textual phrases are simply an indication that older unknown reductions pre-date the Cruel Miller and were used in its creation. It's clear that some of the new text found in the Cruel Miller-- is either from an unknown traditional text, from an unknown reduction, or recreated by the broadside writer(s).

Ballad identifiers- Cruel Miller (short broadside) compared to the Berkshire broadside "Whittam/Wittam" and "Oxford" are removed; "Wexford Town" is introduced.

1. The first two stanzas of Berkshire Tragedy have been eliminated. His ("tender" has been removed) parents educated him (the location, Wittam/Whittam/Witham Town, has been removed) and bound him to a miller, to which they all agree. He courts a "pretty" girl or maid (no longer an "Oxford lass") whose "wanton eye" (Berkshire) becomes "dark (black) and rolling eye." The promise of marriage if "with him she will lie" remains.

2. He courts her for six months "a little now and then" and is ashamed to marry because he "is too young a man." When she is with child, she (not her mother as in Berkshire) demands that he will marry her or else she'll die (how prophetic!).

3. He goes to his sister's house at 8 o'clock (same in both) to take her for a walk (no date, premonition of murder or motive is given in Cruel Miller). He strikes her with a stick "on the crown" or "to the ground" in the Cruel Miller (instead of "in the face" as in Berkshire or the Lexington Murder).

4. She still pleads for mercy but the murder is abbreviated. The blood of the innocent is still mentioned but he goes to "his master's house at 10 o'clock" instead of to the mill where his "man" (the miller) questions him.