The Douglas Tragedy- Scott 1803- Child B

[Child B must be dated 1802 but ti was published in 1803 The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Volume 3 page1 with excellent notes by Sir Walter Scott (see below). Scott's headnotes on the Douglas Tragedy are followed by the Child B ballad text. The music appears in Robert Chambers' Twelve Romantic Scottish Ballads: With the Original Airs, Arranged for the Pianoforte (1844) [Click here to view piano score from Chambers in 1844]]

THE DOUGLAS TRAGEDY reprinted from Poetical Works, Volume 1 By Sir Walter Scott, 1823. Original commentary in Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Volume 3, 1803. This edition was edited by Thomas Finlayson Henderson, 1903.

The ballad of 'The Douglas Tragedy' is one of the few to which popular tradition has ascribed complete locality. The farm of Blackhouse, in Selkirkshire, is said to have been the scene of this melancholy event. There are the remains of a very ancient tower, adjacent to the farmhouse, in a wild and solitary glen, upon a torrent, named Douglas burn, which joins the Yarrow, after passing a craggy rock, called the Douglas craig. This wild scene, now a part of the Traquair estate, formed one of the most ancient possessions of the renowned family of Douglas; for Sir John Douglas, eldest son of William, the first Lord Douglas, is said to have sat, as baronial lord of Douglas burn, during his father's lifetime, in a parliament of Malcolm Canmore, held at Forfar.—Godscroft, vol. i. p. 20.

The tower appears to have been square, with a circular turret at one angle, for carrying up the staircase, and for flanking the entrance. It is said to have derived its name of Blackhouse from the complexion of the Lords of Douglas, whose swarthy hue was a family attribute. But, when the high mountains, by which it is enclosed, were covered with heather, which was the case till of late years, Blackhouse must have also merited its appellation from the appearance of the scenery.

From this ancient tower Lady Margaret is said to have been carried by her lover. Seven large stones, erected upon the neighbouring heights of Blackhouse, are shown, as marking the spot where the seven brethren were slain; and the Douglas burn is averred to have been the stream, at which the lovers stopped to drink: so minute is tradition in ascertaining the scene of a tragical tale, which, considering the rude state of former times, had probably foundation in some real event.

Many copies of this ballad are current among the vulgar, but chiefly in a state of great corruption; especially such as have been committed to the press in the shape of penny pamphlets. One of these is now before me, which, among many others, has the ridiculous error of 'blue gilded horn,' for 'bugelet horn.' The copy, principally used in this edition of the ballad, was supplied by Mr. Sharpe.[1] The three last verses are given from the printed copy, and from tradition. The hackneyed verse, of the rose and the brier springing from the grave of the lovers, is common to most tragic ballads; but it is introduced into this with singular propriety, as the chapel of St. Mary, whose vestiges may be still traced upon the lake to which it has given name, is said to have been the burial-place of Lord William and Fair Margaret. The wrath of the Black Douglas, which vented itself upon the brier, far surpasses the usual stanza:—

'At length came the clerk of the parish,

As you the truth shall hear,

And by mischance he cut them down,

Or else they had still been there.'[2]

The ascription of 'complete locality' to this ballad is of little account, so long as the personages have not been identified. But the introduction of a Douglas into the ballad is probably merely the freak of some reciter, or hack-balladist, for the version is very corrupt, incidents and phraseology being borrowed from the 'William and Margaret,' and 'Lord Thomas and Fair Eleanor' ballads, etc. In the analogous recitation—'Earl Brand'—we have a similar incident to that of the 'Scarlet Cloak':—

'Gude Earl Brand I see blood';

'It's but the shade o' my scarlet robe.'

The seven hostile brethren are, of course, common to several ballads, and were probably buried neither at Blackhouse, nor any other where. In this instance they are perhaps borrowed from 'Fair Margaret's Misfortune' (black-letter in the Roxburghe and Douce Collections, reprinted in Roxburghe Ballads, ed. Ebsworth, vi. 641), as is also this stanza in the stall-copies amended by Scott:—

'Lord William he died ere middle o' the night,

Lady Margaret long before the morrow;

Lord William, he died for pure true love,

And Lady Margaret died of sorrow.'

The story of the intertwining plants is, in substance, common to many other ballads, but St. Mary's Kirk is, of course, Scottish. In a rare Scotticised version of 'Lord Thomas's Tragedy' (white broadside, dated 22nd April 1776), it reads :—

'Lord Thomas was buried in St. Mary's,

Faire Eleanor in the quire,

And out at Lord Thomas their sprang a bush,

And from fair Eleanor a brier.

And these two grew, and these two threw [throve]

Until that they did meet,

Whereby any person, they might know,

That these were lovers most sweet'

In preferring the 'Douglas' to the 'Earl Brand' version of the ballad, Scott seems to have been influenced by Border predilections ; for although he received copies both from Heber and Laidlaw of the then unpublished ' Earl Brand,' he makes no allusion to it. The fragmentary 'Child of Elle ' utilised by Percy is another version of the same ballad; and of several Scandinavian analogues the closest are the older versions of ' Ribold and Guldborg.'

It is the most fatefully tragic of all the lover tales. The lover having killed the lady's father as well as her brethren, the best that could befall him was to be mortally wounded. But in the Douglas version the eternal triumph of love is symbolised by the introduction from other ballads of the story of the intertwining shrubs. For similar stories of lover plants see Hartland's Legend of Perseus, i. 198-201, and for various forms of the superstition that trees are animated by the souls of the dead, see especially Frazer's Golden Bough, 1901, vol. i. pp. 178-187.

The variations from the stall-copy are too numerous for indication. The bulk of them are evidently emendations of the nurserymaid corruptions.

------------------------------

Footnotes:

1. [In a letter to Scott, dated 5th August 1802, Sharpe writes: 'The Douglas Tragedy was taught me by a nurserymaid, and was so great a favourite, that I committed it to paper as soon as I was able to write' (Correspondence, I. 135).] Sharpe is Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe, Esq. (Scott).]

2. At the time when Sir Walter Scott was collecting the materials for this work, the farm of Blackhouse was tenanted by the father of his attached friend, and in latter days factor (or land-steward), Mr. William Laidlaw. James Hogg was shepherd on the same farm, and in the course of on* of his exploring rides up the glen of Yarrow, Sir Walter made acquaintance with young Laidlaw and the 'Mountain Bard,' who both thenceforth laboured with congenial zeal in behalf of his undertaking.— J. G. L.]

____________________________

Earl Brand- Child Version B

Scott's Minstrelsy, III, 246, ed. 1803; III, 6, ed. 1833; the copy principally used supplied by Mr. Sharpe, the three last stanzas from a penny pamphlet and from tradition.

THE DOUGLAS TRAGEDY

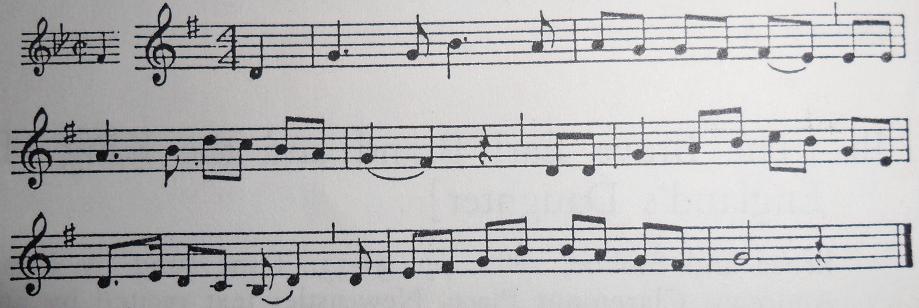

(Melody from Bronson- originally Bb)

[Click here to view piano score from Chambers in 1844]

1 'Rise up, rise up, now, Lord Douglas,' she says,

'And put on your armour so bright;

Let it never be said that a daughter of thine

Was married to a lord under night.

2 'Rise up, rise up, my seven bold sons,

And put on your armour so bright,

And take better care of your youngest sister,

For your eldest's awa the last night.'

3 He's mounted her on a milk-white steed,

And himself on a dapple grey,

With a bugelet horn hung down by his side,

And lightly they rode away.

4 Lord William lookit oer his left shoulder,

To see what he could see,

And there he spy'd her seven brethren bold,

Come riding over the lee.

5 'Light down, light down, Lady Margret,' he said,

'And hold my steed in your hand,

Until that against your seven brethren bold,

And your father, I mak a stand.'

6 She held his steed in her milk-white hand,

And never shed one tear,

Until that she saw her seven brethren fa,

And her father hard fighting, who lovd her so dear.

7 'O hold your hand, Lord William!' she said,

'For your strokes they are wondrous sair;

True lovers I can get many a ane,

But a father I can never get mair.'

8 O she's taen out her handkerchief,

It was o the holland sae fine,

And aye she dighted her father's bloody wounds,

That were redder than the wine.

9 'O chuse, O chuse, Lady Margret,' he said,

'O whether will ye gang or bide?'

'I'll gang, I'll gang, Lord William,' she said,

'For ye have left me no other guide.'

10 He's lifted her on a milk-white steed,

And himself on a dapple grey,

With a bugelet horn hung down by his side,

And slowly they baith rade away.

11 O they rade on, and on they rade,

And a' by the light of the moon,

Until they came to yon wan water,

And there they lighted down.

12 They lighted down to tak a drink

Of the spring that ran sae clear,

And down the stream ran his gude heart's blood,

And sair she gan to fear.

13 'Hold up, hold up, Lord William,' she says,

'For I fear that you are slain;'

''Tis naething but the shadow of my scarlet cloak,

That shines in the water sae plain.'

14 O they rade on, and on they rade,

And a' by the light of the moon,

Until they cam to his mother's ha door,

And there they lighted down.

15 'Get up, get up, lady mother,' he says,

'Get up, and let me in!

Get up, get up, lady mother,' he says,

'For this night my fair lady I've win.

16 'O mak my bed, lady mother,' he says,

'O mak it braid and deep,

And lay Lady Margret close at my back,

And the sounder I will sleep.'

17 Lord William was dead lang ere midnight,

Lady Margret lang ere day,

And all true lovers that go thegither,

May they have mair luck than they!

18 Lord William was buried in St. Mary's kirk,

Lady Margret in Mary's quire;

Out o the lady's grave grew a bonny red rose,

And out o the knight's a briar.

19 And they twa met, and they twa plat,

And fain they wad be near;

And a' the warld might ken right weel

They were twa lovers dear.

20 But bye and rade the Black Douglas,

And wow but he was rough!

For he pulld up the bonny brier,

And flang't in St. Mary's Loch.